levee across Curles Creek (red arrow) blocks public access to land submerged below Curles Creek that may be private, based on a crown grant

Source: US Geological Survey, Hopewell 7.5 minute topographic quad (2010)

levee across Curles Creek (red arrow) blocks public access to land submerged below Curles Creek that may be private, based on a crown grant

Source: US Geological Survey, Hopewell 7.5 minute topographic quad (2010)

The US Supreme Court determined in 1876:1

State ownership is not limited to submerged lands in the Tidewater zone. The General Assembly has established state ownership of the land underneath rivers and streams, except under two conditions. If a parcel of land was included in a grant issued prior to 1792 in that part of the State draining to the Atlantic Ocean, or a grant issued prior to 1802 in that part of the State draining toward the Gulf of Mexico, then the private landowner rather than the state may claim the submerged land.2

When land ownership disputes are not resolved by negotiation or regulation and both sides have the resources to pursue a court case to conclusion, judges in state courts may determine whether a stream is navigable and use that decision as a proxy for defining state ownership.

In 1955, the Virginia Supreme Court determined in Boerner v. McCallister that the Jackson River upstream of Covington was not navigable, in part because the floating of logs downstream to a mill at Covington had been abandoned. That case had been brought by a fisherman who objected to the adjacent property owner's claim to own the bed of the river. The angler hoped that a navigability determination would establish state ownership of the submerged land and therefore public access to the riverbed, but the state court ruled the Jackson River was not navigable.

Over 20 years later, a Federal agency saw the issue differently. The US Army Corps of Engineers ruled in 1978 that the Jackson River was navigable between Back Creek and Covington, including the same stretch that had been considered by the Virginia Supreme Court. The ruling was based on past use of the stream for floating logs, though that use occurred only in 1902 and 1903 for the last 11 miles between Kincaid and Covington.3

A key part of the Federal test of navigability, used to trigger jurisdiction based on the Commerce Clause in the US Constitution, was its potential to be used for commercial traffic after "reasonable improvement." This was articulated in the 1940 United States v. Appalachian Electric Power Co. US Supreme Court decision, which determined that the New River was navigable up to Allisonia:4

Navigability is only a part of the ownership puzzle. Virginia asserts ownership to submerged lands below the Mean Low Water mark on all navigable and non-navigable streams. Despite that state claim, riparian landowners who can trace private ownership back to a pre-1802 or pre-1792 grant may establish ownership of the submerged bottom.

Even when a stream is defined as navigable by administrative action by a state or Federal agency, or by a judge, portions of riverbeds may be declared to be private property. State ownership of the submerged lands underneath inland as well as underneath tidal waters can be blocked, if landowners have sufficient documentation and sufficient funds to pursue a case in court.

Along the Jackson River, on Johns Creek, on Curles Creek, and at Carter's Cove, landowners have convinced state judges that their property ownership claims to submerged land are valid. The landowners proved in court that their grants were made before application of the American common law concept that the rivers were a public trust, and state courts have ruled that the King's Grants/Crown Grants conveyed all ownership to specific parcels. Within the boundaries of those parcels, landowners can exclude the public from the shoreline and sue for trespass if anglers or boaters step onto rocks in the middle of the river.

The challenge to state ownership began on the Jackson River. It had been ruled to be legally navigable by the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1978, but navigability does not always guarantee public ownership of the submerged lands underneath the river. Property owners along the river claimed ownership of the river bed, as well as the land above the low water mark, based on land grants issued when King George II was appointing the royal governors who signed the property transfer documents.

The issue of riverbed ownership ended up in the state courts because of trout.

Mitigation for environmental damage by construction of the Gathright Dam included creation of a new trout fishery on that river, downstream of the new dam. Because Lake Moomaw behind the dam was so deep, the Corps of Engineers could draw from different water depths and discharge a steady colder-than-normal water into the Jackson River. The cold water from the bottom of the lake supported the introduction of trout into the Jackson River.

the Jackson River flows from Lake Moomaw to the headwaters of the James River (at the confluence with the Cowpasture River near Iron Gate)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries was happy to expand the opportunity for fishing, and began to stock trout in the cold water in 1989 after completion of the Gathright Dam. Not all local landowners welcomed the prospect of additional anglers and boaters floating on their isolated stretch of the Jackson River.

Several sued to block public use by claiming private ownership to the bed of the Jackson River. If the riverbed was private property, then the landowners could post No Trespassing signs and keep a stretch of the river private. The water and the fish might belong to the state, but if the riverbed was private property, then an angler would need the landowner's permission to stand in the middle of the river and enjoy fly-fishing. The Alleghany County Circuit judge ruled the riverbed was private property, not submerged land owned by the state of Virginia.

The Virginia State Supreme Court affirmed that ruling in 1996. The court decided in Kraft v. Burr that colonial deeds transferred the riverbed as well as the land above the river banks into private ownership. On June 1, 1750, during the reign of King George II, the colonial government in Williamsburg granted William Jackson 270 acres. On July 14, 1769, during the reign of George III, colonial officials processed a 93-acre grant to Richard Morris. The current owners of the land spent $30,000 to trace their title back to those grants. The courts ruled that the rights to the riverbed that were conveyed in those particular colonial grants were still valid, but did not expand the ruling to affect all the other grants that were awarded in Virginia.

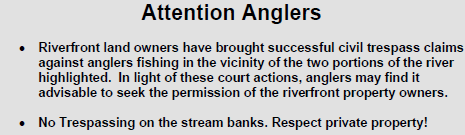

The court decisions enabled four riparian property owners to block public use of the Jackson River below the Mean Low Water line, essentially creating private fishing rights from .75 mile below the dam down to Johnson Springs. The water in the river remained public and boaters could legally float the river, but any contact with the riverbed created a risk of being charged with trespassing on private property.

After the Kraft v. Burr decision in 1996, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries stopped stocking trout below Gathright Dam. The stocking was intended to promote public fishing opportunities - but if the river was not going to be open to the public, then the state agency decided it would treat the Jackson River below Gathright Dam like a private farm pond and no longer use taxpayer funds to stock fish.5

Jackson River fishing access below Gathright Dam

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (DGIF), 2013 Jackson River Tailwater Map

The legal disputes regarding ownership and public access rights continue on the Jackson River as well as on other rivers in Virginia. The River's Edge development on the Jackson River has claimed privileged access to four miles of river frontage, and advertised 33 homesites on 46 acres as having restricted access rights for fishing:6

To force a decision on ownership rights, a Jackson River developer and property owner charged an angler for trespassing. The local Alleghany District Court judge dismissed the case.

The developer and property owner then filed a civil lawsuit, North South Development v. Garden, claiming damages to their private property rights that were based on a 1743 grant awarded in the time of King Charles I. The Attorney General of Virginia declined to intervene in 2012, saying the civil lawsuit was a private dispute and no interest of the Commonwealth was involved. The Attorney General's office stated:7

The angler, Dargan Coggeshall, sought to establish state ownership of the riverbed so he could stand on the bottom of the river while fly-fishing. The landowners sought the opposite, to block public access. Continuing the litigation was too expensive, despite assistance from the Virginia Rivers Defense Fund to generate contributions, so the lawsuit was settled without a final decision by the judge regarding ownership of the riverbed.

Jackson River, below Gathright Dam

Source: US Geological Survey, Falling Spring 7.5 minute topographic quad

The advocates for state ownership of the submerged lands, who supported public access, expressed frustration that the Virginia Attorney General would not participate in the case in order to define and protect the state's ownership claims:8

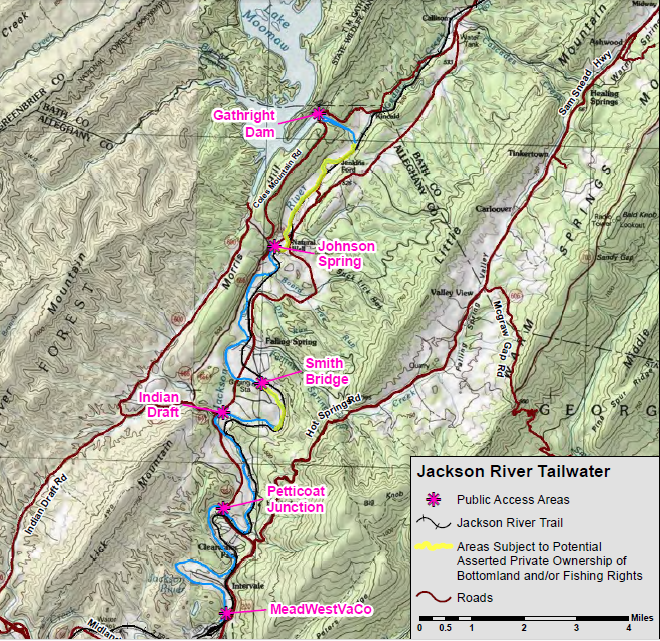

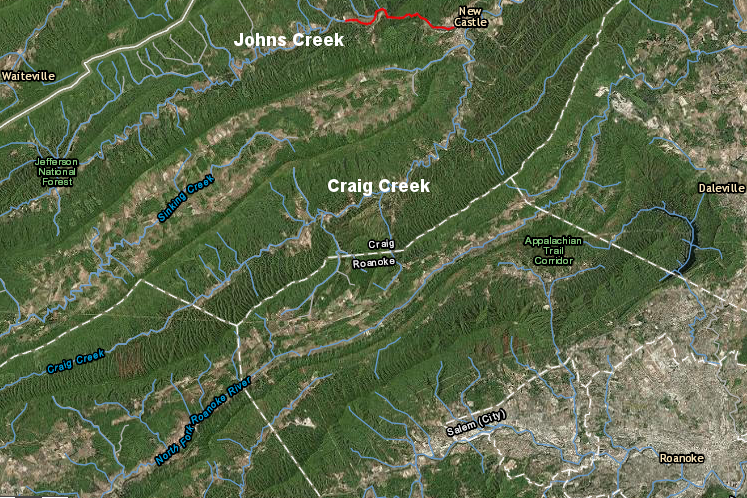

Johns Creek is in the James River watershed, so Kings Grant claims must document land transfers prior to 1792

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1999, Johns Creek in Craig County was closed to recreational boating after a landowner with property on both sides of the stream made a Kings Grant/Crown Grant claim. He asserted ownership of the bottom since the stream was not navigable, and blocked boaters from passing through his property. A kayaker who floated the stretch to test the claim was fined $50 for trespassing.

The potential impact of Kings Grant/Crown Grant claims has not been quantified. Legal disputes such as North South Development v. Crawford could end up affecting streams include the Hazel, Jackson, York, Elizabeth, Cowpasture, James and Shenandoah rivers plus several creeks. As noted in one report:9

One option is legislative action. Landowners claiming private property rights and recreational boaters claiming public access want to avoid the expensive process of getting site-specific decisions through Kings Grants/Crown Grants lawsuits. Neither side has been able to get the state legislature to clarify the status of submerged lands.

After the Kraft v. Burr decision (1996) and the refusal of the Attorney General to protect public access to the Jackson River in North South Development v. Garden (2012), recreational boaters lobbied the General Assembly to pass new legislation clarifying what stream bottoms were state-owned. Those efforts failed, but in 2015 State Senator David Marsden found another technique.

He requested the VMRC to make an administrative decision to declare 14 specific Virginia streams to be navigable. The request cited the criteria adopted by the VMRC to define what stream bottoms come under the state agency's jurisdiction, based on an opinion by the Attorney General of Virginia in 1982:10

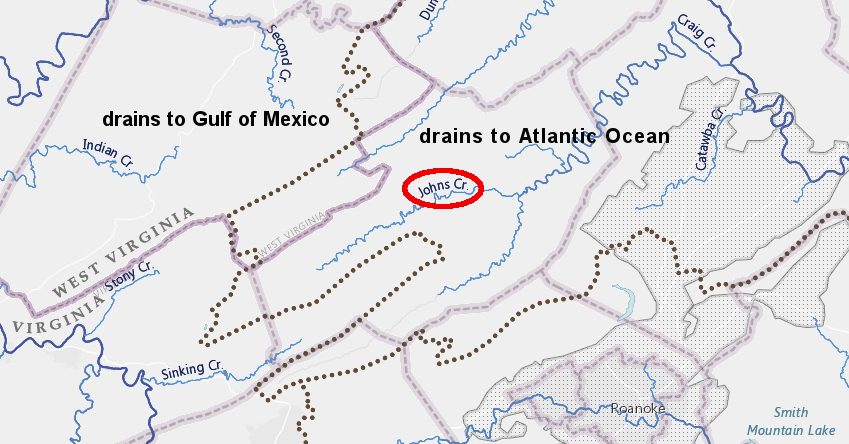

In 2015 the VMRC reassessed 14 streams and declared them to be navigable-in-fact, based on the watershed size exceeding five square miles. That decision on navigability also established a presumption of state ownership to the submerged lands below the Mean Low Water mark of specific segments of Johns Creek (Craig County), Barbours Creek (Craig County), Bullpasture River (Highland and Bath counties), Piney River (Amherst and Nelson counties), Irish Creek (Rockbridge County), Passage Creek (Shenandoah and Warren counties), Cedar Creek (Shenandoah County), Gooney Run (Warren County), Colliers/Buffalo Creek (Rockbridge County), Potts Creek (Craig and Alleghany counties), Jennings Creek (Botetourt County), North Creek (Botetourt County), Wolf Creek (Tazewell and Bland counties), and the North Fork of Blackwater River (Franklin County).

the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) determined administratively in 2015 that Passage Creek was a navigable stream between the Elizabeth Furnace Recreational Area and Route 55, so the submerged land below the Mean Low Water mark was owned by the state of Virginia rather than adjacent riparian landowners

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

After the VMRC declared in 2015 that the contested segment of the Johns Creek was navigable and therefore the submerged bottom there was owned by the state, the Craig County Commonwealth's Attorney declared he would no longer prosecute cases based on trespass claims. Boaters renewed recreational use of Johns Creek in Craig County.11

The administrative declaration by the VMRC shifted the burden to any riparian landowner seeking to block angling/boating on those 14 stream segments. Landowners will have to absorb the legal costs if they wish to establish title based on a Kings Grant/Crown Grant issued prior to 1792 (for streams draining ultimately to the Atlantic Ocean) or 1802 (for streams flowing to the Gulf of Mexico).12

The declaration of navigability by the state agency, and the associated claim of state ownership of the bottom of Johns Creek, could still be overturned. Landowners went to the expense of filing a court case, hoping to successfully establish a King's Grant/Crown Grant issued prior to 1802 and asking a judge to rule that the submerged bottom had been transferred out of colonial/state ownership.

George Washington claimed lands along the Kanawha River before 1792 - and submerged land even below navigable waters may be owned by the state

Source: Library of Congress, Eight survey tracts along the Kanawha River, W.Va. showing land granted to George Washington and others

The decision could also be reversed by future members of the VMRC, appointed by future governors. A third option is legislative action. The General Assembly always has the option to pass legislation modifying the state's claims to bottomlands, or to constrain the funding or authority of the VMRC.

The 2015 declaration by the VMRC spurred other landowners along Potts Creek in Alleghany County to contact their House of Delegate member. They hoped to retain the ability to block recreational use and potential trespass onto the shoreline without having to prove private ownership of the creekbed through a King's Grant/Crown Grant.

The landowners threatened to quit paying taxes on the land underneath Potts Creek, but that threat had limited leverage. The state agency that made the navigability decision would not be affected by withheld payments of property taxes.

Property owners could assert that their local taxes should be reduced because the size of their parcels has been reduced, with the creekbed being state land. The Alleghany County tax assessor is unlikely to lower the assessed value of a parcel significantly by eliminating just the creekbed from taxation. The value of the remaining upland is not affected substantially by the ownership of the creekbed. The submerged land is not suitable for crops, grazing, forest products, or housing, so its value would be minimal when determining local property taxes.13

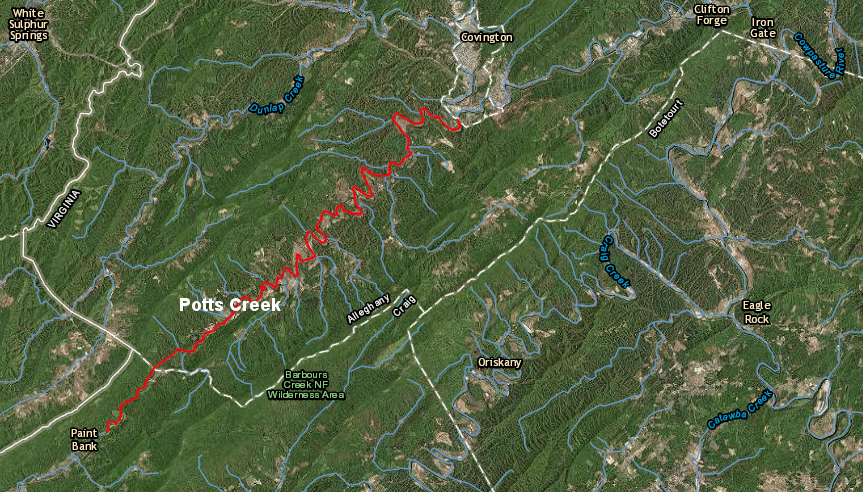

in 2015, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) declared Potts Creek and 13 other streams to be navigable because they had watersheds greater than five square miles

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The primary impact of the navigability decision on local landowners is the potential loss of privacy. Even if boaters and anglers stayed on just the water of Potts Creek as they floated downstream, social impacts created simply by the presence of strangers could be significant. Realistically, some boaters and anglers might trespass on private land beyond the low water mark to use the bushes as a bathroom.

a 2015 administrative declaration by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) opened a stretch of Johns Creek to boating (red line)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

As one landowner noted:14

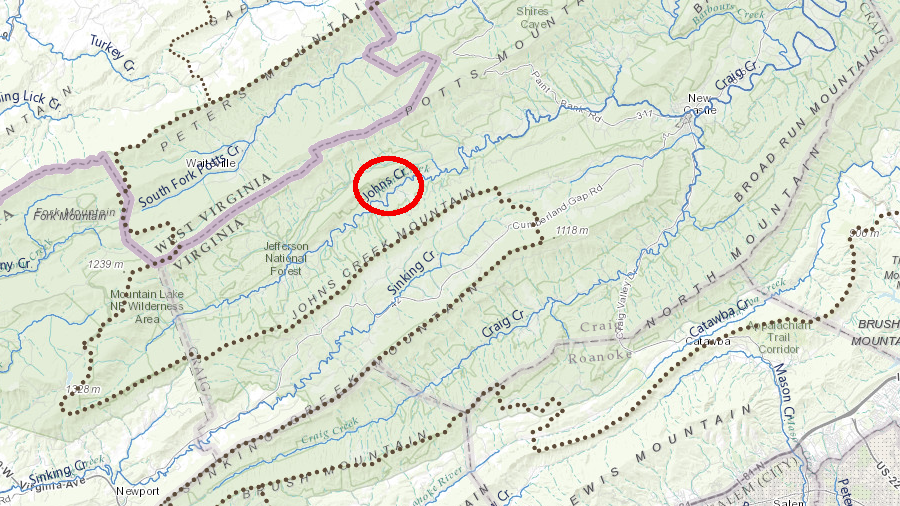

after the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) declared Johns Creek to be navigable in 2015, four landowners filed a lawsuit

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

After the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) declared Johns Creek to be navigable in 2015, opening it to recreational boating, four landowners filed a lawsuit. They claimed the decision was an illegal "taking" (condemnation) of their private property, acquired through Kings Grants issued in 1760, 1770, and 1786 - prior to the 1792 date used in the agency's Subaqueous Guidelines to assert state ownership.

Among the four landowners with property adjacent to Johns Creek was the landowner who succeeded in getting a kayaker fined for trespass in 1999.. They claimed the designation of the stream as navigable, based on having a drainage basin of greater than 5 square miles, created a "taking" of private property (the creek bed) that had been included in Crown Grants issued in 1760, 1770, and 1786.

According to the lawsuit:15

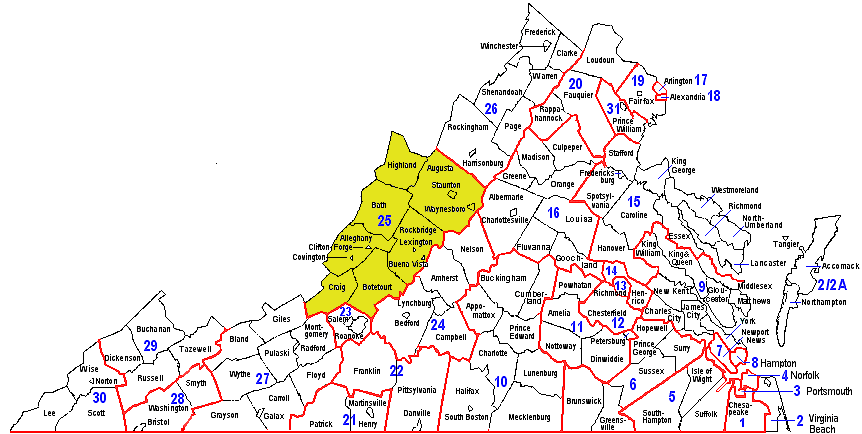

a judge's decision on state authority to declare streams navigable through an administrative process will initially affect just the counties included within the jurisdiction of the Craig Circuit Court (25th Circuit)

Source: Virginia's Judicial System, Map of Virginia's Judicial Circuits and Districts

The lawsuit claimed that the General Assembly had never granted condemnation authority to the VMRC, so the designation violated the Fourth and Fifth amendments to the US Constitution and the Constitution of Virginia. The judge's decision will also be binding on VMRC designation of creeks in Highland County, Botetourt County and Rockbridge County, since they are in the same judicial circuit.

The Board of Supervisors in Craig County was concerned about the economic impact of a ruling that would privatize ownership of the creek bed. Such a ruling would not automatically limit the navigability of Johns Creek, but landowner restrictions could block boat launches from the ford at Virginia 612 where a one-lane public road cross the creek. Any reduction in the number of tourists tubing and canoeing down the stream would affect Wilderness Adventure, a camp and conference center and one of the largest county employers, as well as local restaurants and motels.16

The state government is authorized under the state's constitution to acquire ("take") ownership of private property despite objections of the owners:17

Condemnation requires paying fair market value, and the Code of Virginia elaborates on the process by which land may be taken. Even if the VMRC had the authority to acquire the bed of Johns Creek, the lawsuit claimed that forcing the landowners to prove the creekbed was privately owned in order to receive compensation was a violation of the state's legal code:18

To date, no court has issued a ruling establishing that all King's Grants/Crown Grants claims are valid, or invalid. Each claim has been contested, one lawsuit at a time, and legal guidance emerging from those cases remains vague and confusing regarding title to submerged land.

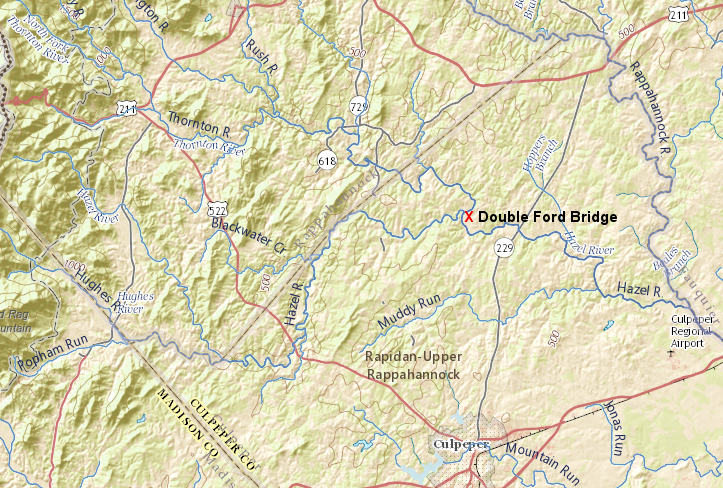

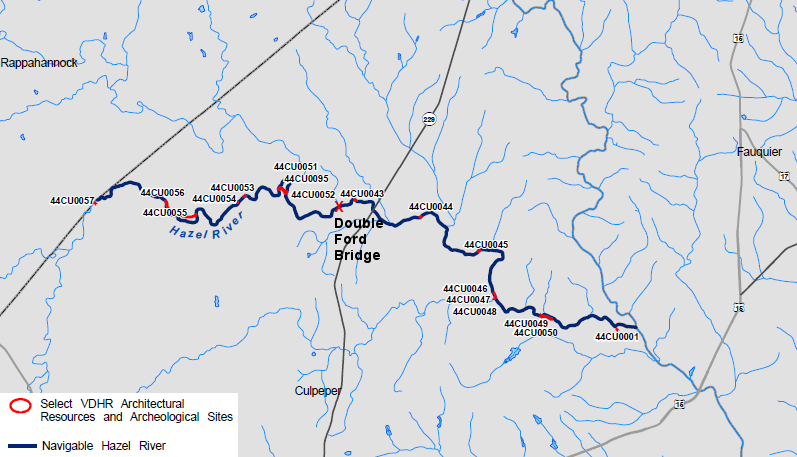

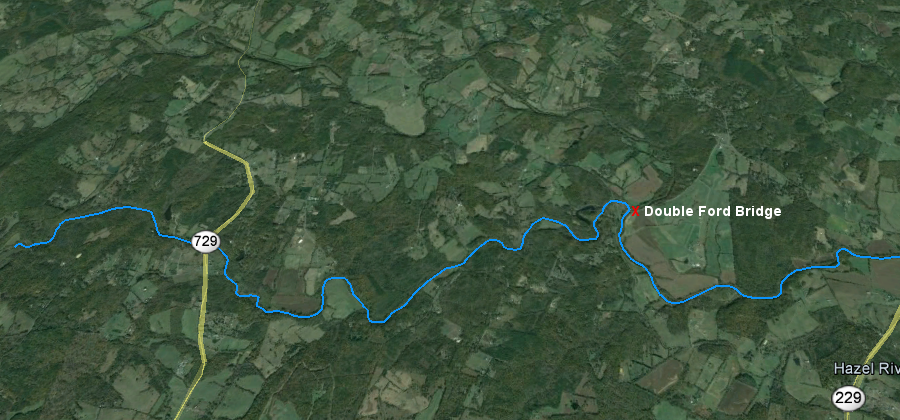

One Kings Grant claim in Culpeper County was triggered by recreational activities that disturbed adjacent landowners near Double Ford Bridge, at the confluence of the Hazel and Thornton rivers.

landowners near Double Ford Bridge, at the confluence of the Hazel and Thornton rivers, convinced the Culpeper County Commonwealth's Attorney for five years that they owned the submerged lands due to Kings Grants

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The landowners convinced the Commonwealth's Attorney for Culpeper County that their Kings Grant claim was valid. The Culpeper County Sheriff did not concur, and would not issue citations based on the Kings Grant claims. For five years between 2005-2010, local law enforcement officials disagreed on whether boaters and swimmers on the Hazel River should be arrested for trespassing, based on the claims by property owners on one side of the river than they owned the submerged riverbed.

A 2007 study of "traditionally navigable waters" in Northern Virginia had documented mills and navigation improvements all the way up the Hazel River to the Rappahannock County border. The county's Commonwealth's Attorney ultimately concluded in 2010 that the general public was legally authorized to float, swim in the river, and use the riverbed between the mean low water lines until a judge ruled otherwise.19

use of the Hazel River for commerce, a traditional basis for determining navigability, was documented far upstream of the Double Ford Bridge

Source: Wetland Studies and Solutions, Inc., Archeological and Historical Determination of Traditionally Navigable Waters in Northern Virginia and a Comprehensive Methodology for the Determination of the Traditional Navigability of Waterways in the United States (p.55)

The Virginia Attorney General has avoided issuing decisions on Kings Grant claims when the state is not an official part of a lawsuit. The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries determined administratively that the Hazel River in Culpeper County past Double Ford Bridge was "inland navigable waters" and subject to that agency's wildlife-related regulations. The Department of Game and Inland Fisheries offers .KMZ files depicting its jurisdiction over inland navigable waters on a Google Earth map, but the state agency has accepted that the Kings Grant claims on the Jackson River may block public access even to streams thought to be navigable.

according to the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, the Hazel River is navigable in Culpeper County past the confluence with the Thornton River and subject to that agency's regulations

Source: Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Inland - Navigable Waters (displayed in Google Earth)

Removal of the Monumental Mills dam, also in Culpeper County on the Hazel River, was blocked by a Kings Grant claim in 2012. The dam was built in the 1840's to power mills, which ground grain into flour that was downstream to Fredericksburg. In 1929 the Monumental Mills dam was converted to produce electricity. The hydropower plant was abandoned, the dam was partially breached by floods, and by 2012 the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries wanted to build on the success of removing Embrey Dam and increasing fish populations.

The landowner on one side was supportive of the project, which would increase spawning habitat for anadromous fish such as Atlantic shad and blueback herring, but the landowner on the other side of the river objected. That claim of private ownership to the middle of the Hazel River halted plans for the removal of the Monumental Mills dam.20

removal of Monumental Mills dam was blocked by a Kings Grant claim in 2012

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Dam Removal in Virginia: "Dammed If You Don't, Undammed If You Do"

Kings Grant claims are not limited to just the Blue Ridge and Valley and Ridge physiographic provinces. In Lancaster County, the Virginia Supreme Court ruled in 1983 that colonial land grants issued in 1642 included the bed of Carter's Creek, even though it was a navigable stream.

The state claimed that King Charles I was constrained by the Magna Carta and lacked authority to grant the submerged land to individuals, so any colonial-era could not include the creekbed. That court rejected that argument. The decision blocked the VMRC from leasing the bed of Carter Cove for oyster grounds, and the Virginia Supreme Court said the owners of the three colonial patents affecting 2,160 acres of land were:21

the submerged bed of Carter Cove became private property when grants were issued in 1642, as confirmed by a 1983 decision of the Virginia Supreme Court

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Irvington US 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013)

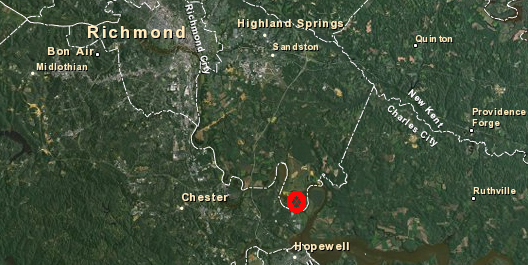

In 1968-69, Curles Neck Farm and Dairy (in the Tidewater portion of Henrico County) built a 4,800-foot long berm which included an 800-foot long, 7-foot high levee across the mouth of the Curles Creek where it flowed into the James River.

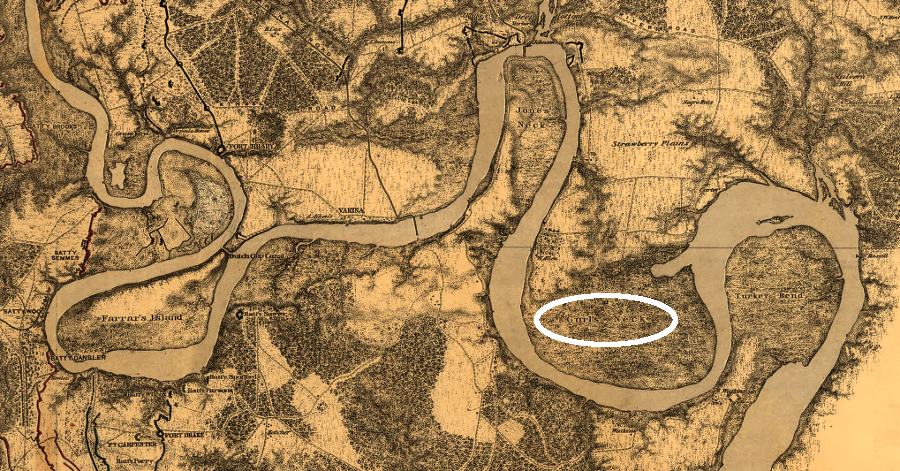

Curles Creek is located north of the James River, near Bermuda Hundred on the southern side

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

By adjusting gates in the levee, water levels were controlled after 1969. Each July, the water was drained from behind the levee, millet was planted, and productivity of wetland plants was maximized in order to improve waterfowl hunting potential at the site. Each October, flow through the gates was adjusted again, allowing water to flow back behind the levee.

The levee transformed Curles Creek into a flooded marsh with high-quality habitat for duck hunting from the adjacent private property, similar to "moist soil management areas" operated at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge. Back in 1916, long before construction of the levee, the site was already renowned as "the best ducking marsh in the South."22

Curles Neck is one of several major bends in the James River

Source: Library of Congress, Bermuda Hundred [1864-1865]

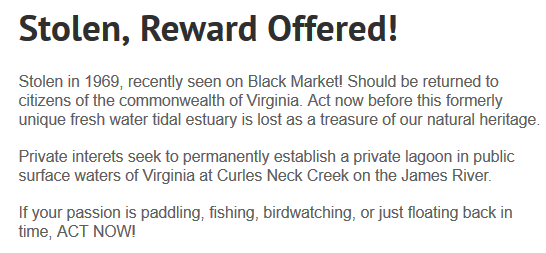

The levee also blocked the public from access to allow waterfowl hunting in Curles Creek, and the VMRC claimed 300 feet of the structure trespassed on state-owned submerged land. Countering the state's claim, the landowner cited a 1691 grant to Richard Cocke; no state permit for the levee would be required, because the creek bottom was private property.

In 1989, twenty years after the levee was constructed, both parties agreed to an after-the-fact permit legalizing the Curles Creek barrier, but the Henrico County Circuit Court consent decree specifically excluded any determination of ownership based on the colonial-era land grant.23

In 2013, the new owners of the 5,400 acre Curles Neck Farm requested a VMRC permit to modify the levee and build a half-mile steel sheet pile wall. The wall, with riprap scour protection, would reinforce the levee against rising sea levels and ensure the wetlands would not become open water. Dredging for the construction would require a state permit for use of State-owned bottomlands, so VRMC action was required again.

In 1989, over 50 people had objected to the after-the-fact permit. (The permit was never signed by the applicant, so no formal authorization was ever executed based on the consent decree.) In 2013, two neighbors objected to the permit, proposing instead that the levee should be breached and public access restored to Curles Creek.. However, the local state senator, Henrico County, Ducks Unlimited and the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Rice River Center supported the permit.24

One possible reason that environmentally-oriented organizations supported the landowners was their statement that they would not subdivide Curles Neck Farm. Suburban sprawl would have greater impact on the natural resources at Curles Creek than retaining the levee.

Granting a new VRMC permit would limit public use at one location and preserve the exclusive hunting access rights of a few property owners, but an administrative decision to authorize the new construction also bypassed the ownership issue. If VRMC had refused the permit, the property owners at Curles Neck might have funded a major legal fight and won a sweeping decision on Kings Grant claims, potentially restricting public access to tidal creeks throughout Tidewater.

Conservationists were willing to support the Curles Creek levee in part because it encouraged the wealthy landowners to keep their property undeveloped. If conservationists had united with the neighbors to push for removal of the levee, the worst-case scenario was that the landowners would respond by pursuing a lawsuit granting ownership of the creekbed based on their Kings Grant claim.

in 2013, opponents of the VRMC permit made their perspective clear regarding ownership of submerged land at Curles Creek

Source: Curles Neck Creek Tidal Estuary Restoration

The ecological values of the James River marshes in that area are obvious. US Fish and Wildlife Service's 1,329-acre Presquile National Wildlife Reserve, directly across the James River from Curles Creek, attracts as many as 10,000 geese and ducks on the refuge in the winter. Though the Fish and Wildlife Service authorizes hunting for white-tail deer on the refuge, the Federal agency has banned waterfowl hunting there since 1954. Geese and ducks that overwinter on Turkey Island are hunted on public and private lands elsewhere, including adjacent Curles Creek marsh.25

At the Rice River Center, two miles downstream from Curles Creek on the James River, a dam across Kimages Creek was removed to restore the natural tidal flow. The dam had been constructed in the 1920's, creating fresh-water Charles Lake. Many local people and campers at Camp Weyanoke had enjoyed fishing and swimming there, and there was local support for maintaining the dam.

The major modification of the natural landscape was no longer appropriate after VCU acquired the land and started an environmental study center, which focused on how big rivers operate naturally on the Coastal Plain. VCU was able to avoid expensive repair costs after a 2006 storm breached the dam, and it was removed in 2010 without significant controversy.26

in 1994, a dam maintained Charles Lake and blocked the natural flow of brackish water

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Westover 7.5.7.5 topographic quad (1994)

by 2013, natural tidal flow in Kimages Creek was restored (and Camp Wyanoke was VCU's Rice River Center)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Westover 7.5.7.5 topographic quad (1994) and Westover 7.5.7.5 topographic quad (2013)

In the end, the risk of losing a Kings Grant suit had to be compared to the benefits of restoring the natural tidal flow at Curles Creek. If a court ruled that the Kings Grant claim was valid, then residential development of the 5,500-acres Curles Neck Farm could have become the Tidewater equivalent of the River's Edge development on the Jackson River, on a much larger scale.

Curles Neck could have become the first of many subdivisions marketed as "a unique, conservation-based residential community boasting unparalleled access to the finest wild-trout fly-fishing waterfowl hunting on the East Coast."

In May, 2013, after a five-hour hearing, the VMRC issued the permit for expanding the Curles Creek levee in a 6-2 vote. The permit conditions addressed water management and anadromous fish migration concerns, but finessed the conflicting claims to ownership of the submerged land.27

Even if VRMC had won a court case regarding ownership and forced removal of the levee to restore public access to Curles Creek, the ability of the public to hunt waterfowl there could still be limited.

Under the Waterfowl Blind Laws enforced by Virginia's Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (DGIF), riparian landowners get priority for licensing fixed waterfowl blinds. Such blinds can be located each 500 yards, and people in boats may not hunt within 500 yards of any licensed blind, whether it is occupied or not. The landowner adjacent to Curles Creek could build blinds and thus exclude the general public from hunting - though removal of the levee would have opened up the creek for fishing, canoeing, birding, and other wildlife observation activities.28

Charles Lake was eliminated after the dam across Kimages Creek was removed, in contrast to Curles Neck

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Dam Removal in Virginia: "Dammed If You Don't, Undammed If You Do"

the dam for Charles Lake was removed in 2010, after storm damage in 2006

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Dam Removal in Virginia: "Dammed If You Don't, Undammed If You Do"

in 2015, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) declared that much of Jennings Creek in Botetourt County was a navigable stream, so the state (not adjacent riparian property owners) controlled access to the submerged bottom between the Mean Low Water mark on either bank

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online