scientists can access some caves on Cedar Creek (Frederick County) via kayak, where the surface/groundwater connection is obvious

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Valley and Ridge, Piedmont, and Blue Ridge Aquifers

scientists can access some caves on Cedar Creek (Frederick County) via kayak, where the surface/groundwater connection is obvious

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Valley and Ridge, Piedmont, and Blue Ridge Aquifers

Caves are a unique habitat, and very simplified ecosystems due to the absence of light. Animals are far more common than plants in caves. Beyond the cave openings, there is no light for photosynthesis.

Without light, there are no plants. There are bacteria that rely upon chemosynthesis by oxidizing hydrogen sulfide and methane or reducing sulfides rather than carbon. Chemosynthetic bacteria are found at Movile Cave in Romania and hydrothermal vents at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Such bacteria also exist in Virginia, but they have not been found in caves near the surface. Virginia caves rely upon a food web based on photosynthesis, even though there is no light in the cave, as food from the surface is washed in or brought into the cave by animals.

In 1992, companies exploring for oil and natural gas in the Taylorsville basin northeast of Fredericksburg drilled into a pocket nearly two miles underground. They found microbes that relied upon reducing iron or manganese instead of oxidizing carbon. Those microbes had been living without access to the sun since the dinosaurs had left footprints in those sediments, 200-250 million years ago in the Triassic Period.

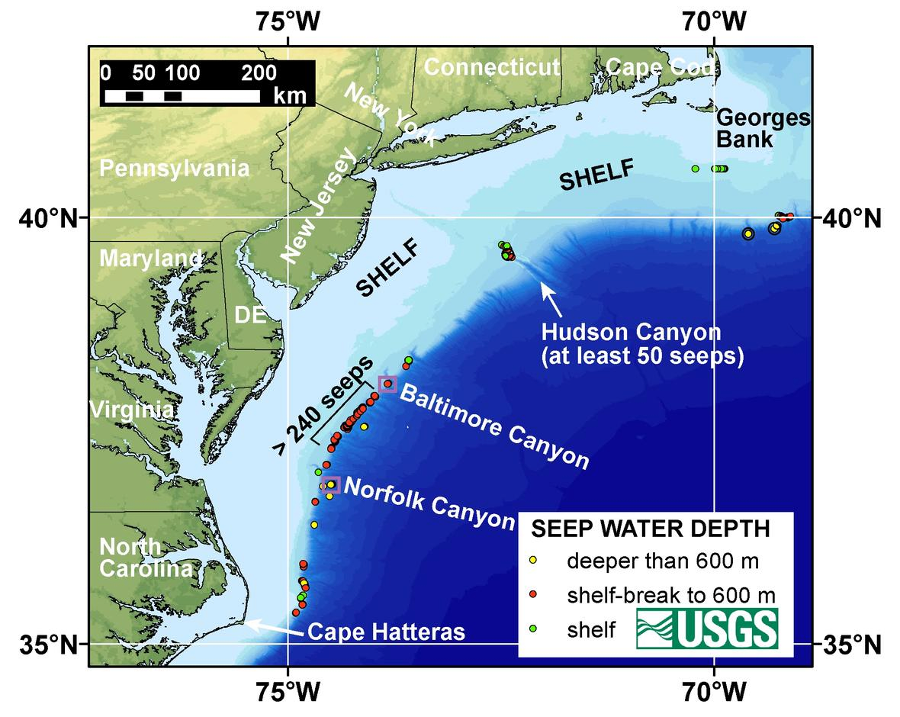

There are also chemosynthetic microbes at methane vents on the Outer Continental Shelf. The methane there has been generated for at least 15,000 years, since sea level rise covered the Outer Continental Shelf. The methane comes from organic matter decomposing in the seafloor sediments, rather than from oil/gas buried in deeper formations.1

microbes use chemosynthetic processes to generate food from methane at seeps on the Outer Continental Shelf, but such microbes have not been discovered in Virginia caves - yet

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Atlantic Methane Seeps Surprise Scientists

The food chain for animals that live exclusively in a Virginia cave is based on the little bit of detritus that washes in during storms, or is brought in by the animals that use caves for shelter but leave the cave for food. Bats feed outside the cave, and return with full bellies. The bats then create great mounds of guano underneath their roosting sites, far from where sunlight can reach. Various forms of life from bacteria to cave crickets can live on the energy provided by that food source.

Some animal species that evolved on the surface of earth have adapted to living within always-dark caves. One common adaptation is a low metabolic rate, since the availability of food is so limited. Bats, which roost in caves but feed outside where food is plentiful, maintain a high metabolic rate.

The technical term for cave animals living in water is "stygofauna." Terrestrial animals are troglofauna. Aquatic animals that survive only within caves, such as blind cave fish, are "stygobites." Terrestrial animals that survive only within caves are troglobytes, There are also stygophiles and troglophiles, animals that thrive better within the protected cave environment but also live outside caves.

There are at least 31 different cave-adapted beetles and eight species of bats living in Virginia caves. Blind cave fish species, troglodytes that survive only within a cave, are found in Tennessee and Kentucky, but all the fish found in Virginia caves washed in from a sinkhole, window, or swallet on the surface or swam upstream into the cave.2

Virginia caves are typically muddy, moist, cool - and dark

Artificial lights installed for commercial cave tours alter cave ecology. Visitors rely upon those lights to walk on the trail, and to see stalactites and other rock formations. Cave lights change a previously always-dark environment. If lights are left on long enough each day, algae spores can germinate and grow on moist cave formations. The chlorophyll used by the algae to photosynthesize food from the artificial light adds an unnatural green color and texture to the cave formations. To minimize the impact, cave guides turn lights on only when tourists are walking through sections of a cave.

The carbon dioxide emitted by cave visitors can affect speleothem formation. The growth of stalactites requires an excess of CO2 dissolved in the groundwater to be released into the atmosphere of the cave, so calcium carbonate will precipitate from droplets evaporating into the cave atmosphere. The National Park Service has documented where high cave visitation altered the air and water chemistry, reducing the growth of cave formations. When visitation was reduced, cave formations began to grow faster.3

In Virginia, caves are too dark for animals to enter very far except for bats. They rely upon a form of sonar rather than eyes to navigate without light. Salamanders, fish, and insects are protected against most predators in a cave. Moist, dark, protected caves offer an attractive habitat.

Larger animals have entered caves, and not all escaped. The four-foot long skeleton of a large cat, perhaps an American cheetah, was found in 2016 inside Burja Cave in Lee County.

After five years of preparation, including training a paleontologist to navigate 100 feet of vertical drops, a team of 11 cavers removed the nearly-complete skeleton. They had to crawl with ropes and gear for an hour inside the muddy cave. The bones, covered by a thin layer of calcite which had accumulated over the centuries, were removed slowly using dental picks and small tools. The fossil, named "Petra," is being studied and displayed at the Virginia Museum of Natural History in Martinsville.

The four-foot long skeleton had been intact, but was broken into smaller pieces in order to carry it through the narrow cave passages. The paleontologist explained:4

The cavers covered the bones in toilet paper and paper towels first, then bubble wrap and closed cell foam normally used for sleeping bag padding. The pieces of the skeleton had to fit into cave packs in order to be hauled up the vertical drops and out of the cave. Some bones, including the skull, were placed in large plastic containers as well.

Its age was estimated at 100,000-500,000 years, but the condition was excellent. One of the cavers who discovered the skeleton commented:5

the skeleton of a Pleistocene cougar or American cheetah was removed from Burja Cave in 2021

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), The Petra Project

Caves are a repository of prehistoric animals that flew or walked in, or fell in, but never escaped. Paleontologists study vertebrate and microvertebrate fossils collected from Starr Chapel Cave in Bath County, Burja Cave in Lee County, and others. Parts of shrews, bats, rabbits, raccoons, snakes, birds, frogs and fish document what entered a cave, or had bones wash into a cave. Even what appears to be a mastodon tooth has been discovered inside a Bath County cave.

Animals continue to get trapped in caves. Cavers exploring Giant Caverns in Giles County in 2024 were surprised to find a dog underground. They collected webbing and managed to wrap the dog in a made-on-the-spot harness, extracted it from the cave, and carry the lost animal to the local shelter.

The floor of Giant Caverns has many bones from animals that previously entered and never escaped. One of the rescuers commented:6

"Facultative" cave dwellers, such as a raccoon or human hunters in colonial days looking for shelter from a rainstorm, use caves when convenient. "Obligate" cave dwellers (stygobites/troglobites) have evolved to the point where they are no longer able to survive outside the cave. Some obligate cave dwellers have lost the use of eyes, which provide no benefit in a cave and require substantial energy to maintain. It is common for troglobites to be white as well, since the energy invested in creating proteins for colors provide no evolutionary advantage.

A reduction in metabolic requirements will enhance survival in a pitch black cave where food resources are very limited. The Lee County cave isopod has evolved so it is white, and does not waste energy growing and maintaining eyes.7

the Lee County isopod is not charismatic megafauna like a grizzly bear, but the first rule of environmental management is to "save all the pieces"

Source: Virginia Tech Extension Service, Endangered Species and Pesticide Regulation

Caves also provide a steady temperature, reflecting the average temperature of the area. Only near the entrance of a cave will the temperature change between day and night, and with the seasons. Virginia caves are about 54-56 degrees, every day, every hour. The one commercial cave in North Carolina, Linville Caverns, is always 52 degrees. It is located south of Virginia but at a higher elevation in the mountains, so its average temperature is cooler.8

Caves are not always a static environment; they can change dramatically at times. A summer thunderstorm can result in a rush of water into a cave, importing leaf debris, raising the temperature, and even drowning bats and breaking cave formations if the cave floods completely.

Humans exploring a cave can also be caught and drowned. Caving clubs known as "grottoes" warn new members to be cautious before entering a wild cave if rainstorms are likely in the area. While underground, people inside a cave will not hear thunder and know to head back to the entrance before water levels might rise and cut off the escape route.

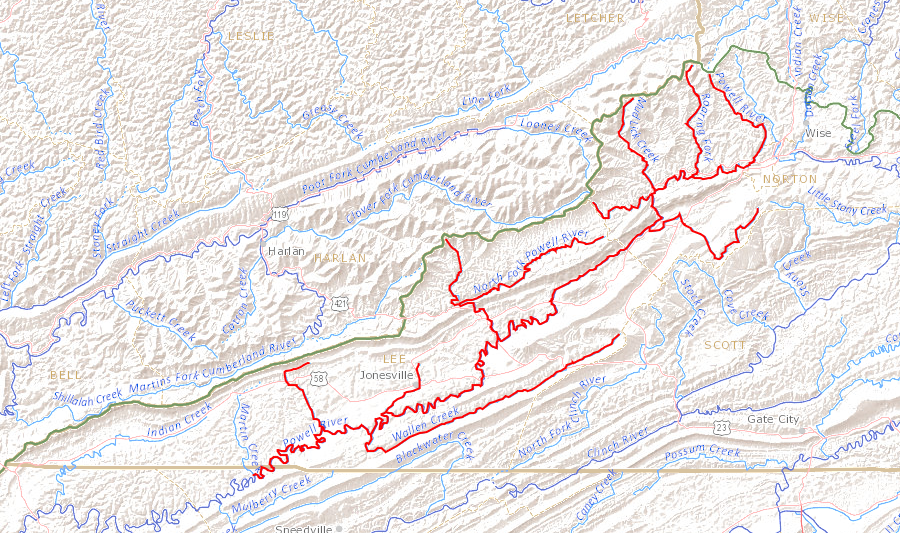

Caves are vulnerable to pollution from the surface. In the karst region of Lee County known as The Cedars, roughly 75% of the water reaching the Powell River travels as groundwater for at least a portion of that journey. Whatever was on the surface - manure from wildlife and cattle, hydrocarbons from highways, pesticides from agricultural operations, etc. - can be carried down into cave systems.9

the Powell River drains the eastern side of Cumberland Mountain on the Virginia-Kentucky border

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

Contaminants and nutrients introduced into the groundwater from surface application of fertilizer, from septic system leach fields, or from stormwater ditches. Whatever flows into sinkholes can reach the cave underneath and affect the sensitive biological balance.

Caves can suffer if the perception is "out of sight, out of mind" regarding waste disposal. Until 2001, the highway maintenance facility for the Virginia Department of Transportation in The Cedars karst region (Jonesville, Lee County) channeled its stormwater runoff directly into a sinkhole.10

In the 1980's, water seeping through piles of sawdust (leachate) from a local sawmill and flowing into Thompson Cedar Cave had very low levels of dissolved oxygen. The pollution appeared to eliminate the cave's local population of the Lee County Isopod (Lirceus usdagalun), which was listed as an endangered species in 1992. After most of the sawdust was removed, water quality improved. Biologists rediscovered the species within the cave in 2002, presumably after survivors in upstream refugia expanded their range into the restored habitat.11

rain seeps underground through sinkholes and porous limestone rock in karst landscapes, carry pollution into caves underground

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy (DMME), Sinkholes and Karst Terrain

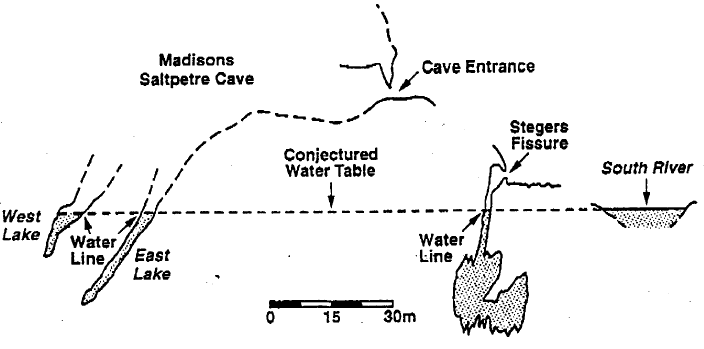

Preservation of the Madison Cave isopod (Antrolana lira) in the Shenandoah Valley faces a similar requirement to conserve the quality of groundwater. The Madison Cave isopod has been found only where fissures link the surface to the groundwater table near Harrisonburg. As described in the Final Recovery Plan:

fertilizer from cropland and manure from livestock can get into the groundwater of caves from small openings in the porous limestone bedrock and via rainwater flowing into larger openings

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Madison Cave Isopod (Antrolana lira) Recovery Plan (Figure 2)