State Capitol, in Richmond |

"downtown" Ballston, in Arlington County |  beaver pond near I-66 in Prince William County |

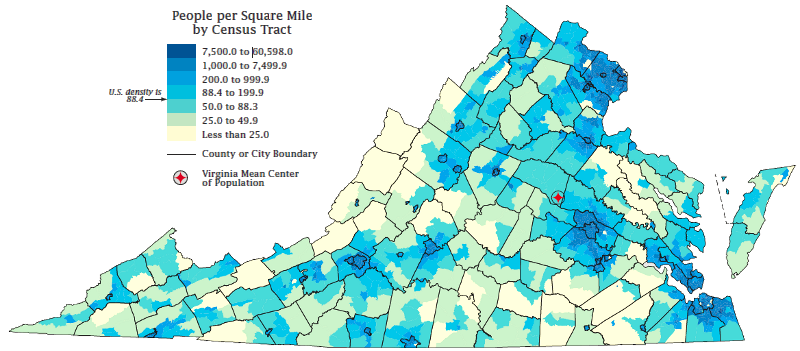

Virginia has about 40,000 square miles of land. There are 640 acres in a square mile, so some quick pecking on the calculator will show that Virginia has over 25 million acres.

The standard suburban tract home is built on a quarter-acre lot (with a white picket fence and a dog, according to the stereotype). The backyards of those homes serve as personal parks for the residents. If we developed every acre in Virginia in the suburban land use pattern, there's enough land for 100 million backyards in Virginia (25 million acres/.25 acres per housing unit...)

We don't have 100 million backyards where everyone can play, of course, because not every acre in Virginia is dedicated to housing - though people living in sprawling suburbs in Hanover County, Chesterfield County, City of Suffolk, Loudoun County, and similar high-growth communities may be wondering when the last fields and forests will be converted to subdivisions.

If you assume all families will live on a quarter-acre lot, we could fit 100 million housing units (with white picket fences, a dog, and 2.1 kids...) into the 25 million acres in Virginia. In this exercise, we're not squeezing 100 million people into Virginia. We would be squeezing 100 million housing units - houses, apartments, condos, trailers, etc. - into Virginia. Because the average occupied housing unit (i.e., each "household") has more than 1 person, we could squeeze more than 100 million people into Virginia... if the entire state was developed into stereotypical suburbia with 1/4 acre lots.

According to the Bureau of Census, the average housing unit in the US ("Persons per household") has about 2.6 people. If we squeezed 100 million housing units into Virginia, developing every acre of land for housing, Virginia could accommodate 260 million people (85% of the entire population of the US).

Some might consider it a nightmare scenario of excessive development, to fill the entire state of Virginia with 260 million people in 100 million households, each on quarter-acre lots. Such a hypothetical "build out" of 100% of Virginia as a suburban neighborhood would eliminate all the natural spaces, and much of the habitat for wildlife. Look around on your next commute to work or to school. You will see paved roads and parking lots, commercial districts, 1-and 2-story townhomes and houses, maybe even tall apartments, rural farms, and undeveloped natural areas (including rivers). There's a great deal of diversity in Virginia's land use pattern, not a standard quarter-acre lot model.

State Capitol, in Richmond |

"downtown" Ballston, in Arlington County |  beaver pond near I-66 in Prince William County |

Roughly 2/3 of Virginians own their own home - check out the "Homeownership rate" statistic on QuickFacts. However, just owning a backyard does not eliminate the desire for public recreation facilities. Not every recreation opportunity is available in the average backyard. Backyards are suitable for summer cookouts and playing with the dog, and a few backyards have a swimming pool - but do you have friends or family with a personal 18-hole golf course, or lake suitable for canoeing? How many friends of yours have a trout stream, or a backyard large enough to allow deer hunting? Does your family own beachfront property on the Atlantic Ocean?

Most outdoor recreational opportunities require a community to invest in acquiring land or building facilities. The most-expensive recreational facilities - major amusement parks such as Kings Dominion and Busch Gardens - are provided by the private sector. Community associations sell memberships to swimming pools in many suburbs. "Country clubs" offer access to golf courses, tennis courts, and a variety of active recreation opportunities as well as a chance to socialize. Private clubs offer restricted access to prime hunting and fishing areas.

In addition, a wide range of public areas are available for everyone to use because the community of citizens, through their government agencies, have acquired land in Virginia for public use. All the land in the state (and even some of the river bottoms and bottom of the Chesapeake Bay) was granted to private individuals since the English arrived in 1607. However, some of Virginia has been re-acquired by the government. Some of the acquired property is used for government office buildings or may be closed to public access (especially military reservations), but examples of public recreation sites managed by different levels of government include:

The location of the public parks, forests, wildlife refuges, etc. are not scattered at random across Virginia. There's a relationship between the physical geography (don't look for ski resorts on the flat Coastal Plain), the density of the population, and the local land use patterns.

People in urban areas are more densely crowded together. Urban residents may have more shopping options, but they have more paved-over areas and less open space with grass and trees. Urban communities have more tax dollars to use in purchasing and developing public recreational areas, such as public golf courses and waterparks with pools and waterslides - but the cost per acre of the urban land is much more expensive.

Local governments tend to invest in small parks for active recreation, especially ballfields near subdivisions. Taxpayers demand that ballfields be located close to where the people live, so local baseball and soccer teams can use them after work during the summer. When a developer "proffers" to build a park, as a condition of approval for a new subdivision in urbanizing Northern Virginia, Richmond, or Hampton Roads, the future residents of that subdivision want the park to be in easy walking distance. (It does not always happen that way, depending upon how county officials approve rezonings and subdivision site plans. For example, in the last 10 years the developers who built new subdivisions on Linton Hall Road in Prince William County, such as Braemar, were allowed to locate "community recreation sites" at Valley View Park, several miles away.)

In most states, urban residents have ballfields nearby but normally have to drive far from their homes to go hiking in a large natural area. For example, in California the Los Angeles residents drive several hours to reach the wide open spaces in the California/Nevada desert, while San Francisco residents escape to Yosemite National Park.

Virginia does not fit that pattern, however. The majority of the Virginia population is concentrated in three places - Northern Virginia, the Richmond area, and Hampton Roads. In the eastern urban concentrations of Norfolk-Virginia Beach-Newport News, Richmond-Petersburg, and Washington, there are several large public parks maintained as natural or cultural areas.

In Northern Virginia for example, the George Washington Memorial Parkway, with a trail along the Potomac River, is right next to Alexandria. Fairfax and Prince William residents can explore over 15,000 acres at Prince William Forest Park and Manassas National Battlefield Park, or nearly ten times that amount at Shenandoah National Park. "Open space" is still nearby for even urban Virginians, so long as they have a car.

The Federal government has designated large areas for public use on the Coastal Plain of Virginia. Civil War battlefields and national wildlife refuges make a surprising amount of open space available in urbanized areas along the Fall Line, and downstream towards the Chesapeake Bay. Federal parkland along the Potomac River provides easy access to walking and biking trails in the most-heavily populated section of the state. In addition, state parks in Virginia Beach (First Landing State Park and False Cape State Park) plus the public beaches along the Atlantic Ocean allow Hampton Roads residents easy access to the oceanfront.

In the smaller cities west of the Fall Line (Bristol, Roanoke, Lynchburg, Danville, and Charlottesville), there is quick access to the Thomas Jefferson National Forest, the George Washington National Forest, and the Blue Ridge Parkway. The Federal government provides vast acreage for outdoor recreation in natural areas throughout Virginia - but if you want to play baseball or soccer on a developed field, then you will have to call your local parks and recreation department or your local school system. Local taxes pay for "active" recreation sites (tennis courts, swimming pools, golf courses, ballfields), while Federal taxes pay for "passive" outdoor recreation sites used for hiking, birdwatching, and hunting.

As the demand for developed "active" recreation sites such as ballfields increases, local governments will increase the supply near the schools and thus the homes of the increasing Virginia population. In some cases, private clubs will meet these needs. However, a clear geographic split between where people live and where they can enjoy natural areas is likely to develop in the near future.

It's hard, if not impossible, to increase the supply of natural areas to match population growth in the urban centers of Virginia. It is too expensive to tear down suburban/urban housing to create new parks. As a result, the population will grow in urban areas and demand for outdoor recreation opportunities will increase, but the supply will still be at a distance. Expect Virginia's rural highways to get more and more crowded with cars, as families travel to "get outdoors." Those people who want to live within walking distance of forests with hiking trails and deer hunting opportunities will have to buy vacation homes or even condos in the woods, in places like Wintergreen Resort, Shawnee Land, or Wilde Acres.

|

|  |

Views from Wintergreen Resort in Nelson County | ||

Population growth is likely to be concentrated in the existing urban areas and the suburbs that ring the cities, with only a small percentage of new residents moving to the rural counties on the Appalachian Plateau or in Southside. It's too expensive now to buy large blocks of undeveloped land in Loudoun, Prince William, Fairfax, or Arlington counties, but the political demand to open up more natural areas will not disappear. The most recent significant land purchase for a state conservation area was the acquisition of Merrimac Farm Wildlife Management Area in Prince William County in 2007.

The likely result of high demand for new public parkland in regions with high land costs: new natural areas in high-density regions will be acquired by the government and opened up to public visitation - but these areas will be small, measured in tens/hundreds of acres. Large natural areas, measured in thousands of acres, will be acquired far away from Virginia's urban areas, because of the lower cost of land where population density is lower.

The state park system looked for land near Northern Virginia, using proceeds from the 2002 bond referendum to acquire and open more parks. The closest they are likely to come to Northern Virginia is Shenandoah County and Stafford County. New lands along the North Fork of the Shenandoah River have been purchased at Toms Brook (in Shenandoah County), and the Widewater peninsula (in Stafford County) will become a state park. The Crows Nest site in Stafford could have become a national wildlife refuge, but the Federal Government shifted focus from land acquisition to the reduction of backlogged maintenance. With strong support from local officials, the State of Virginia purchased Crows Nest and created a "Natural Area Preserve."

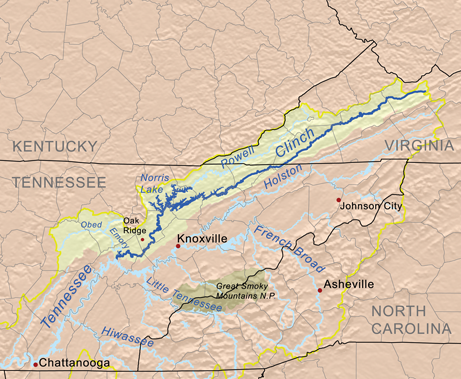

| Some places are more valuable than others. The Clinch River Valley in

southwestern Virginia is one of the top biodiversity "hotspots," with an

unusual richness of species, in the United States. During the last period

of glaciation, the Tennessee River was isolated from other drainages in

the Ohio River watershed. Many species of mussels depend upon fish, in a

complex life cycle, to exchange genes with other mussels in the river. After

the glaciers cut off fish migration, species of mussels in the upper Tennessee

River watershed (including the Clinch River) diverged from each other through

natural evolutionary processes. By the time the glaciers melted about 15,000

years ago, southwestern Virginia was home to many new species of mussels.

The Nature Conservancy has been purchasing undeveloped lands in the Clinch River watershed, in part because the wildlife values are so high for due to the rare species of mussels in that Tennessee River tributary. One Tennessee scientist described the nearby Powell River as1

Another major consideration is that the land in southwestern Virginia is low-cost. Population density there is low, and population growth is low. The demand for land is low, and therefore the prices are low. With limited funding, the Nature Conservancy can protect more land and more miles of river in Southwest Virginia than at Virginia Beach or in Loudoun County, where price/acre is much higher. That's one reason Federal plans to purchase more wildlife refuge acreage in Virginia are centered on the Rappahannock River. A critical mass of land (and wetlands) that is still suitable for geese and deer can be acquired downstream from Fredericksburg, at a lower cost/acre than in Northern Virginia or Hampton Roads. Land would be even cheaper in Buckingham or Cumberland counties... but they are inland, away from the migratory flyways of waterfowl. The cost of land may be low in Buckingham or Cumberland counties, but the "rare and need protection" wildlife values there are also relatively low. The Last Great Places acquisitions of The Nature Conservancy were not designed just to acquire the greatest number of acres at the lowest cost; the goal was to acquire the most valuable habitats.

|

land acquisition costs in the Clinch River basin are far cheaper than in Northern Virginia Source: Wikipedia, Clinch River |

Based on land acquisitions to date for conservation purposes, Pittsylvania County has been less of a priority than protecting areas in Smyth County. You can see the impact of Fairfax County's commitment to protect stream valleys, starting with acquisition of buffer strips along stream channels as county officials approved new subdivisions since the 1960's.

You can also see in Northern Virginia the effectiveness of private conservation organizations, primarily the Piedmont Environmental Council, in establishing conservation easements along the Blue Ridge between Albemarle County and the Potomac River: