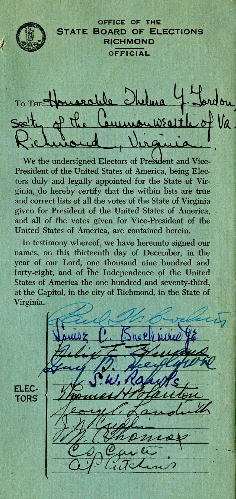

Virginia's 11 members of the Electoral College met at the State Capitol in 1948 and certified that Harry Truman had won the presidential election in the state

Source: Library of Virginia, Electoral College Digital Collection Released

Virginia's 11 members of the Electoral College met at the State Capitol in 1948 and certified that Harry Truman had won the presidential election in the state

Source: Library of Virginia, Electoral College Digital Collection Released

When the US Constitution was ratified in 1788, Virginia had the largest population of the 13 states. It was given 12 votes of the 81 votes in the Electoral College for the 1789 presidential election, while Pennsylvania and Massachusetts were given 10 each.

Those Virginians who were eligible to vote chose one elector each in 12 separate election districts.

However, one of the 12 voting districts did not return results, so only 11 Electors were chosen and one of those did not cast a vote. The 10 electors who participated, each cast two votes as described in Article II of the US Constitution. All electors from the 10 states who participated in the 1789 Electoral College process voted for George Washington, but the electors split their second vote among different candidates. Washington received 69 votes and became President. John Adams received the second-highest number, 34 votes, and became Vice-President.

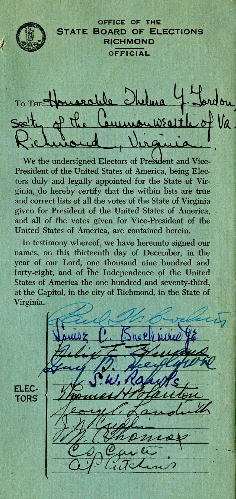

in 1789, only Patrick Henry "stood for election" to be chosen as an elector in District 10

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

The total of the 20 votes cast by the 10 electors from Virginia were:1

George Washington - 10

John Adams - 5

George Clinton - 3

John Jay - 1

John Hancock - 1

The mechanism of electing one person in separate districts was used for the first three presidential elections, with one district per elector. In some districts there was only one candidate for elector, such as in District 10 where only Patrick Henry sought the role in 1789. In other districts, members of the elite competed with each other to be chosen. All were supportive of George Washington in the first two elections, but split their votes for the other candidate who then became Vice-President.

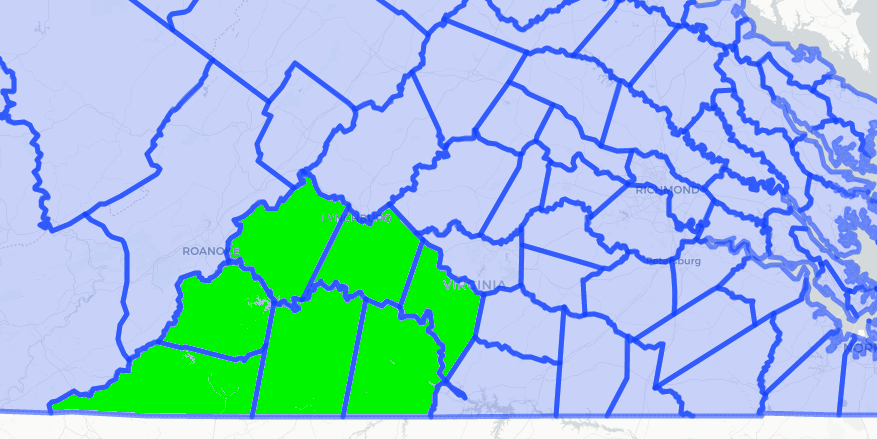

After the 1790 Census, Virginia was allocated 19 members in the House of Representatives. The General Assembly divided the state into 21 new districts for voters to choose one elector per district.

in the 1790's, voters chose individual electors in 21 separate districts rather than selected a statewide slate

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries

In 1792, the Virginia electors cast 21 votes for George Washington and another 21 votes for George Clinton. Washington was re-elected president in 1792, unanimously again, because all electors in the other 14 states voted for him. However, all electors did not support George Clinton. Some electors voted instead for John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Aaron Burr. The count of the electoral votes for two candidates were transmitted to Philadelphia, where the US Congress declared Washington to be President and John Adams to be Vice-President again on February 13, 1793.

In 1796, each elector again cast two votes as described in Article II of the US Constitution. In nine of those states, the legislatures had chosen the electors. In Virginia and six other states, they had been chosen by popular vote. Virginia's 21 electors cast a total of 42 votes in the Electoral College:2

Thomas Jefferson - 20

Samuel Adams - 15

George Clinton - 3

George Washington - 1

Thomas Pinkney - 1

Aaron Burr - 1

John Adams - 1

The one Virginia vote for John Adams came from the elector in District 21, consisting of Loudoun and Fauquier counties. Federalist Leven Powell was opposed to planter aristocracy. After he founded the town of Middleburg, he named the streets after Federalist leaders such as Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Pinkney.

In District 21 in the 1796 election, Powell won 592 votes while Democratic-Republican Albert Russell captured only 313 votes. Powell became the only Virginian to cast his Electoral College vote for John Adams, along with one other southerner from North Carolina. Adams won the presidency with 71 votes in the Electoral College. He needed 70 for a majority, so the two electoral votes he received from Virginia and North Carolina provided the margin of victory.

Thomas Jefferson received a total of 68 electoral votes and became Vice-President. In the first presidential election where political parties were a factor, the country ended up with a Federalist President and a Democratic-Republican Vice-President. It is the only time members of two rival political parties were elected together, though later there were splits between Presidents and Vice-Presidents after their election together.

After the 1796 election, Alexander Hamilton lobbied the electors in hopes of preventing John Adams from becoming President. Thomas Pinckney had run together with Adams, with a clear understanding that Adams was the candidate for President and Pinckney for Vice-President.

Hamilton proposed all Federalist electors should vote for Pinkney, but some should withhold votes for Adams. That scheme would make Pinkey the President and Adams, with fewer votes, the Vice-President. Hamilton's scheme was focused on South Carolina electors, since Pinkney was from South Carolina. The maneuver backfired, in part because in 1796 slow communications prevented electors from coordinating their actions on the day they met. Federalist electors who supported Adams decided not to vote for Pinkney:3

Starting in 1800, all Virginian voters chose a statewide slate of electors rather than vote in separate districts, but each district had one member of the slate. Since 1800, the presidential candidate who has won a plurality of the popular vote has received 100% of the electoral votes from Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson had urged the switch from single-elector district voting, which split the state's electoral votes by the winner in each Congressional district, to awarding all of Virginia's electoral votes to just one person. In a 1968 decision by the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Williams v. Virginia State Board of Elections, the judges rejected an effort to force the state to allocate its electoral votes by district. They noted Jefferson's reasoning in their decision:4

Political parties choose the electors who will be on the slate. Every four years the voters make clear their preferences for candidates when they vote for a slate of electors, but the only Virginians who ever vote directly for a president are the electors, Virginia's members of the "Electoral College."

The 1800 election was the last in which each elector voted for President, and the candidate receiving the second-most votes became Vice-President. After the 1796 experience, none of the electors supporting the Democratic-Republican ticket withheld a vote for Aaron Burr to ensure he would get at least one less vote than Thomas Jefferson. As a result, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr each received 73 electoral votes. With the tie, no one had a majority.

As planned by the Constitution, the 1800 choice for President was made by the House of Representatives, in which each of the 16 states had one vote. Burr refused to acknowledge Jefferson was the "top" candidate who should become President, and the final decision by the House of Representatives to choose the second President from Virginia came only after a lengthy process.

To avoid a repeat, Article II of the US Constitution was modified by the 12th Amendment. Since 1800, electors have cast a specific vote for President and a separate vote for Vice-President. Candidates have run for President without a partner running for Vice-President and candidates have run for Vice-President without being tied to a Presidential candidate, as in 1840.

In 1824, John C. Calhoun ran for President but ended up as Vice-President. He was the second choice of advocates for both John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. While those advocates split on the choice of President and forced the decision into the House of Representatives, electors who supported both candidates cast their second vote for Calhoun and elected him as Vice-President.

The 12th Amendment does not eliminate the potential for another tie. In the 2020 election, both Joe Biden and Donald Trump could have ended up with 269 votes in the Electoral College, forcing the decision to the House of Representatives to choose the President. Both Kamala Harris and Mike Pence could have received 269 electoral votes, forcing the decision to the US Senate to chose the Vice-President.

After the initial vote in 1789, the allocation of electoral votes has been based on the number of members in the US Senate and House of Representatives. All states always have two Senators. However, the national census every 10 years determines the population, and may alter how many members of the House of Representatives are allocated to a state.

The 1810 election was the last in which Virginia had the greatest number of votes in the Electoral College. Reallocation of representation in the House of Representatives after the 1810 Census resulted in New York getting 27 members. With two senators, New York ended up with 29 electoral votes. Virginia and Pennsylvania each were allocated 25 members in the House of Representatives, and thus 27 electoral votes.

The size of the House of Representatives has changed over time as well as the number of residents in each state. Virginia lost significant population with the creation of Kentucky in 1792 and West Virginia in 1863, and the state has never regained its former role as a dominant force in national elections. In the 2020 presidential election, Virginia had 13 electoral votes while California had 55.5

The formula for determining the number of members each state would have in the House of Representatives was one of many compromises made at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. The southern states were granted extra political power by including 3/5 of the enslaved people when determining the population of each state. Though often described as a racist decision to enhance the power of slaveowners, the 3/5 formula had been developed earlier for a different purpose.

The formula was based on a compromise in 1783 which was designed to punish the southern states by counting 3/5 of the enslaved people when determining the amount of taxes due to the national government. That tax formula was recycled in 1787 to determine the population to be counted for representation in the House of Representatives.

The Confederation Congress was designed to be a weak national government, and always struggled to collect funding from the more-powerful state governments. In 1783, the Congress sought authority to tax imported goods. An "impost" tax would affect the northern states the most, since shipping activity was greater in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia compared to the major southern post at Charleston.

Initial efforts to authorize a 5% impost failed, due to sectional disputes reflecting the different sectional impacts. Advocates for generating adequate revenue for the national government made a second proposal, for a 2.5% impost plus a supplemental tax based on a state's population. The supplemental tax would generate the revenue that would be lost by cutting the impost to 2.5%, and was to be generated by a formula based on a state's total population.

To balance the tax burden equitably between northern and southern states, the backers of the proposal designed it so southern states would pay extra. That was accomplished by including 3/5 of the enslaved people in calculating total state population, so southern states would pay a 15% higher percentage of the supplemental tax. Southern states with 41% of the white population would pay 47% of all supplemental taxes.

The 2.5% impost plus supplemental tax proposal was also rejected by the Confederation Congress. Failure to adopt any formula to generate adequate revenue left the national government unable to perform a key function. The Confederation Congress could not fund military defense against Native American raids in the western borderlands or European threats along the Atlantic coastline.

The failure of the initial form of national government, based on the Articles of Confederation, led to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. After ratification in 1788, the new Constitution replaced the Articles of Confederation with a new form of national government. The new Federal structure could finance military responses, after a series of compromises designed to ensure all states felt adequately represented.6

One of those compromises was to create an indirect process for choosing the president and vice-president. The idea that the president and vice-president should be elected by popular vote was controversial during the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

Under the "Virginia Plan" introduced by James Madison, the national legislature would choose the chief executive for a fixed term of 6-7 years, and reappointment would be prohibited. That matched the approach used in Virginia at the time. After 1776 the General Assembly chose the governor for a one-year term, and he (only males were eligible...) could serve a maximum of three consecutive terms.

The compromise solution was to improve the balance of power among the three branches of the new Federal government. The people, rather than the US Congress, would elect the President. However, those meeting in Philadelphia in 1787 feared that direct election of the President might result in an uneducated electorate (a "mobocracy") choosing a charismatic individual who could become a tyrant/king. The Constitution created a process for indirect election. Each state was authorized to choose electors through whatever process it wanted, and then those electors would choose the president and vice-president. That would allow the electors to block a demagogue from becoming President, while still preventing the US Congress from having excessive power.

States were allocated electors in part based on their population, but every state had at least 3. In the new US Congress, each section of the United States had the ability to block a national policy which would be unacceptable to a region, but individual states lost their veto power over national action.

In the 1787 Constitutional Convention, the compromise proposal that created the Electoral College was crafted by the Committee of Unfinished Parts. The compromise that based presidential elections in part on state populations (including 3/5 of the enslaved people) gave the southern states greater political power, reassuring them that the new Federal government would not be able to force an end to slavery.

Since 1789 the electors in each state have met, voted, and sent their results ultimately to the president of the U.S. Senate (i.e., the Vice-President) for official tabulation of the President.

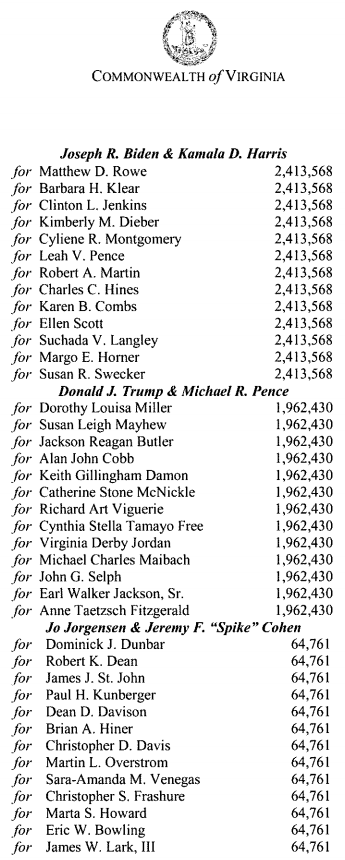

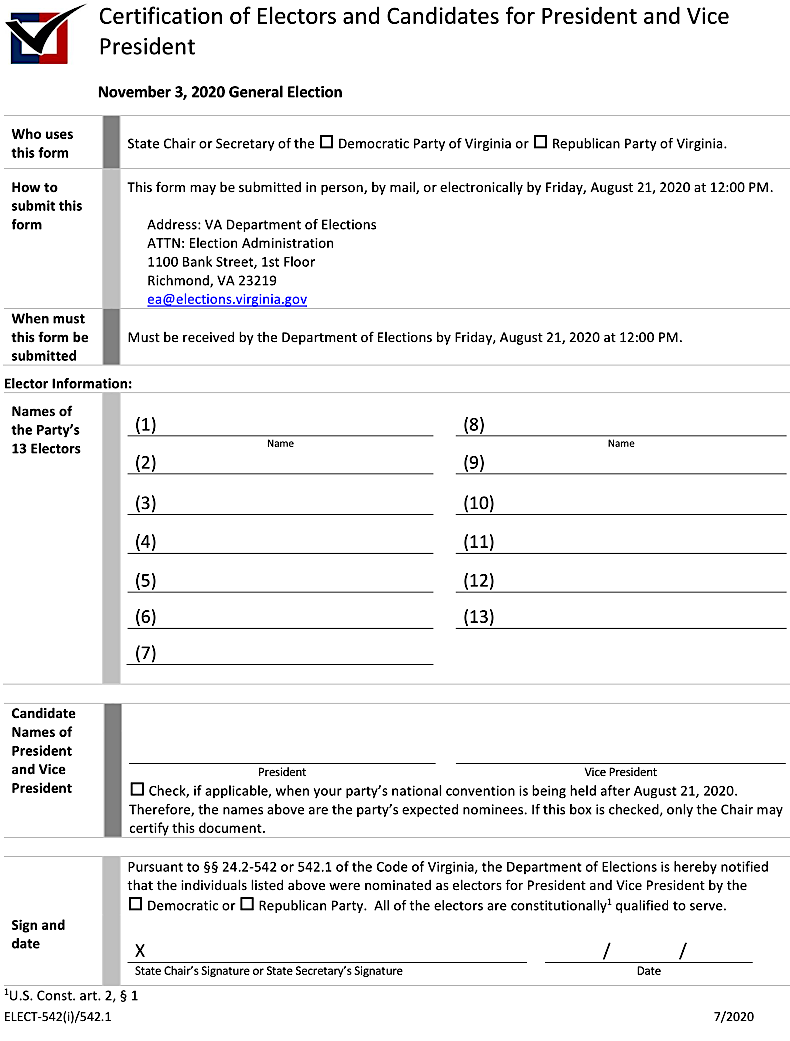

The modern process in Virginia includes a meeting of the State Board of Elections to report the official, certified vote count. The governor then signs a Certificate of Ascertainment which lists, by name, the electors for each candidate and the number of votes each received.

the 2020 Certificate of Ascertainment documented votes for three slates of electors, since that year three candidates for President and Vice-President were on the ballot

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Certificate of Ascertainment (December 8, 2020)

After the electors meet in each state, the Certificate of Ascertainment recording the winner of the electoral votes in Virginia is sent to the National Archives in Washington, DC. The Archivist at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) forwards all state-supplied reports of their electors to the president of the Senate, who is the Vice-President.

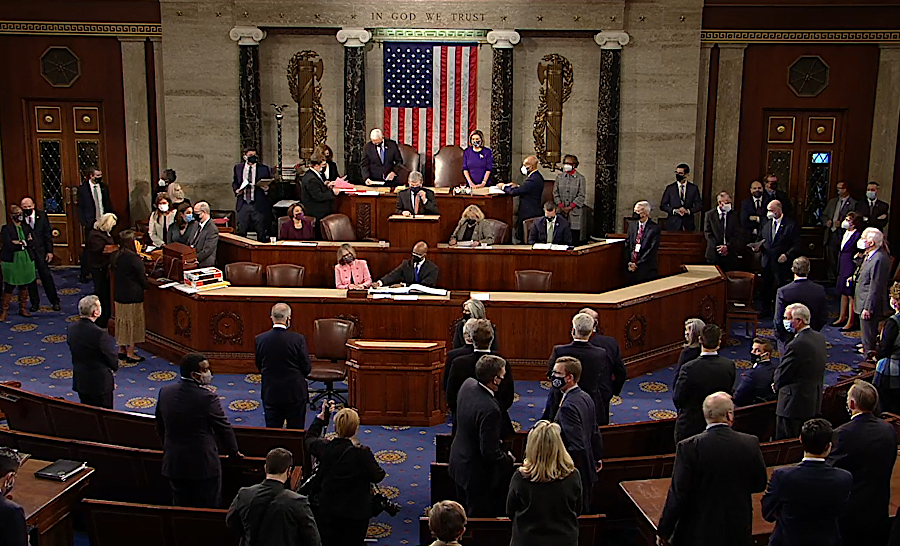

The totals for each state are read at a joint meeting of the two houses of Congress on January 6. In 2021, demonstrators invaded the US Capitol on January 6 in hopes of disrupting the count and blocking Vice-President Mike Pence from reading the results that Joseph Biden had won a majority of the electoral votes. The attack on the Capitol was designed to help President Donald Trump remain in office beyond the end of his term.

the 2021 attack on the Capitol included chants to "Hang Mike Pence" in order to block the President of the Senate from reading of the Electoral College results

Source: Tyler Merbler, Gallows V

Virginia always plans to complete recounts and resolve all challenges to votes within 35 days after the election. The 1877 Electoral Count Act law established the significance of that date. Completing a state's vote count within the deadline creates a barrier to state-level election challenges, a "safe harbor" for electors to know their results will be considered official when opened by the president of the US Senate:7

The electors then meet in the State Capitol 41 days after Election Day (the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December) to officially cast their 13 votes for the winning candidate. The results are sent to Washington DC, where the president of the Senate opens the votes at a joint meeting of the Senate and House of Representatives on January 6.

Each state sends multiple certified copies of the vote by electors to Washington, to ensure that the state's decision is documented. In 2021, a mob stormed the Capitol during the count of electoral votes. The intruders could have destroyed/altered the documents, except staff fleeing the House of Representatives chamber and two Senators took with them the mahogany boxes with the election certificates from the states.

Federal law specifies the requirements in detail:8

in 2021, documents submitted by the states were protected by staff who grabbed the mahogany boxes when a mob stormed the Capitol and breached security

Source: Twitter, Sen. Jeff Merkley (January 6, 2020)

With rare exceptions, candidates win a majority of electoral votes, the official submissions are not challenged, and the announcement of the winners in the joint session of the US Congress involves no drama. Two exceptions were in 1800 and 1824, when the failure of any candidate to achieve a majority triggered a referral to the House of Representatives for selection of a President and to the Senate for choice of a Vice-President. Once, in 1876, multiple slates of electors were submitted to the president of the Senate. A unique process was used to resolve the conflict, resulting in Rutherford B. Hayes getting a bare majority of the electoral votes and becoming President in 1877.

The Constitution determined that the US Senate would choose the Vice-President if no one receives a majority of the Electoral College votes. That has happened in 1800 and in 1837. In 1824, John C. Calhoun won a majority of votes for Vice-President while the choice of a President was referred to the US House of Representatives.

Virginia's electors have at times been "faithless," ultimately voting for a candidate other than the person they supported on Election Day. In 1836, Presidential candidate Martin Van Buren had teamed with Kentucky Senator Richard Mentor Johnson on the Democratic Party ticket. In that election, the pair defeated multiple candidates nominated by the emerging Whig Party.

Van Buren and Johnson clearly won the 1836 election in Virginia. However, Johnson had made one of his enslaved women a common-law wife. His behavior, including the birth of two interracial children, scandalized the Virginia electors. All 23 chose to be faithless electors and cast their Vice-President ballots for William Smith of Alabama instead. As a result, Johnson received only 147 electoral votes - one less than the majority of 148. The US Senate, dominated by the Democrats, quickly chose Johnson to serve. That problem was avoided in 1840, when Martin Van Buren chose to run for re-election alone without any candidate for Vice-President. Johnson ran for re-election on his own in 1840, but both were defeated by the Whig ticket of Virginia-born William Henry Harrison and Virginia-resident John Tyler ("Tippecanoe and Tyler too").9

The Constitution allows each state to determine its own procedures for choosing electors. In many states, presidential electors were chosen by the legislature initially. Virginia always selected electors by popular vote, though restrictions on who could be a voter blocked participation by women until 1920 and limited access by minorities until the 1960's.

In two presidential elections, Virginia cast no electoral votes. In 1864, Virginia had seceded from the Union and joined the Confederate States of America; there were no Virginia electors for either Abraham Lincoln or George McClellan that year. In 1868, Virginia was governed as Military District #1 under the Reconstruction laws. For a second time, along with Texas and Mississippi, Virginia did not participate in the Electoral College.10

The Constitution makes no reference to any electoral "college." The electors meet on a specific day which is set by Congress, but gather in 50 individual states and the District of Columbia. They never assemble altogether in one place, in order to cast their votes as a body. As a result, the electors have less opportunity to engage in horse-trading among themselves and negotiate to vote for a candidate who had not received the most votes in their state.

To increase the legitimacy of the final Electoral College decision, by 2020 there were 33 states that had passed laws that require their electors to cast their ballots for the candidate who won the most votes in their jurisdiction. The District of Columbia has done the same. In 15 of those states, electors could be punished in same way for being a "faithless elector" and voting for someone else. The leadership in state political parties controls the nomination of electors and selects loyal partisans, but occasionally someone will "go rogue."

Before the 2020 election, electors had cast 23,507 electoral votes in 58 elections. In some years, electors have not appeared as scheduled to cast a vote. In those years, the state's submission of its electoral vote total was lower than authorized.

Only one elector ever has voted for the opponent rather than for their candidate. In 1796, an elector in Pennsylvania was pledged to John Adams. He voted instead for Adams' rival Thomas Jefferson.

There have been 164 other electors who did not vote for the presidential candidate or vice-presidential to whom they were pledged. In 1872, 63 of them were supporters of Horace Greeley, the Democratic Party candidate defeated by Ulysses S. Grant. Greeley died before the Electoral College met, creating a unique circumstance. Three of his 66 electors still voted for him.

Virginians have been involved in other faithless elector decisions, beyond the one who supported Thomas Jefferson in 1796 and the 23 who defected from Vice-Presidential candidate Richard Mentor Johnson in 1836. In 1808, six electors of the Democratic-Republican Party from New York failed to vote for James Madison as President. Instead, they cast ballots for George Clinton, who was Thomas Jefferson's Vice-President and running with Madison in 1808. Clinton was a former governor of New York, and had failed to get the party's nomination but evidently retained some supporters.

In 1820 an elector for James Monroe in New Hampshire cast his vote for John Quincy Adams, who was not a candidate that year. No one had run against Monroe in 1820, but the elector was faithless because he felt that unanimous support was not appropriate.11

After John F. Kennedy narrowly defeated Richard M. Nixon in 1960, some electors sought to alter the outcome. All eight of the Mississippi electors and six of the eleven from Alabama were not pledged to any candidate. Kennedy had won those two states, which were part of the "Solid South" supporting Democrats ever since Reconstruction. However, the Democratic leadership in those states was concerned that Kennedy's support for civil rights might trigger more changes in the traditions and laws that maintained segregation and suppressed non-whites.

One option was to switch the electoral votes and choose Lyndon B. Johnson as President and relegate Kennedy to the powerless office of Vice-President, and an alternative was to withhold enough electoral votes to throw the choice to the House of Representatives. The advocates for blocking Kennedy also suggested that all of Nixon's electors should join with them to choose a person who had not run in 1960 as President. The Governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, encouraged electors to choose Sen. Harry F. Byrd of Virginia as President and Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona as Vice-President.

The effort fizzled in the end. Kennedy received 303 electoral votes, and needed only 269 for a majority. However, 15 electors (one faithless elector from Oklahoma, plus eight unpledged electors from Mississippi and six from Alabama) cast votes to Sen. Harry F. Byrd rather than Kennedy. All 14 of the South Carolina electors supported Kennedy for President, but voted for Sen. Strom Thurmond rather than Sen. Lyndon Johnson for Vice-President.

In 1961, as president of the Senate, Vice-President Nixon opened the 50 envelopes submitted by the electors in each state and read the results. Going alphabetically as specified by Federal law, Nixon read the results from Alabama first. After announcing five votes for Kennedy from the pledged electors and six votes for Byrd from the unpledged electors, Nixon demonstrated his sense of humor by pausing to comment:12

In 1972, a Virginia elector pledged to Richard Nixon voted instead for the Libertarian presidential candidate. In 2016, Vice-Presidential candidate Tim Kaine was deserted by 5 electors, but faithless electors from Colorado and Minnesota were replaced according to state law so those votes went to Kaine.

The US Supreme Court ruled in its 2020 case Chiafalo v. Washington that electors are not free agents; state laws that replace faithless electors could be enforced. There were no "faithless" electors in 2020.13

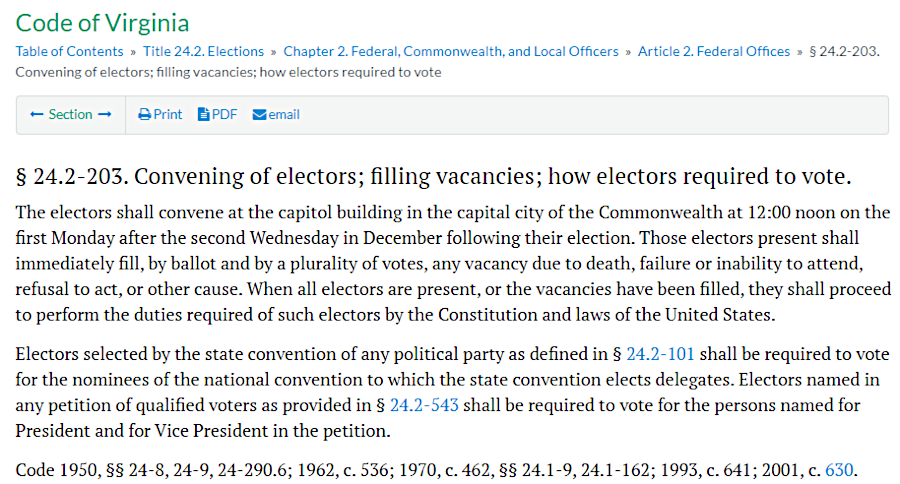

Virginia in one of the 33 states in which electors are required to vote for the candidates of the political party which nominated them. There is no penalty imposed on a Virginia elector who might cast a vote for a different person, and no provision to replace such an elector immediately so all of the state's 13 electoral votes reflect the candidate who won a majority of the popular vote. Virginia is one of 48 states, plus the District of Columbia, that use the winner-take-all approach to allocating electoral votes. Only Maine and Nebraska do not apply the unit rule and allow more than one candidate to receive electoral votes.14

the Code of Virginia has no provision for punishing or automatically replacing faithless electors

Source: Code of Virginia, Section §24.2-203. Convening of electors; filling vacancies; how electors required to vote

Multiple presidents have been elected without winning a majority of the popular vote - John Quincy Adams (1824), James Polk (1844), Zachary Taylor (1848), James Buchanan (1856), Abraham Lincoln (1860), James Garfield (1880), Grover Cleveland (1884, 1892), Benjamin Harrison (1888), Woodrow Wilson (1912, 1916), Harry Truman (1948), John F. Kennedy (1960), Richard Nixon (1968), Bill Clinton (1992, 1996), George W. Bush (2000), and Donald Trump (2016).15

Between 1992-2020, Democratic candidates had received more votes nationwide than the Republican candidate in every election except in 2004, but George W. Bush and Donald Trump still became president in 2000 and 2016 because they captured a majority of votes in the Electoral College. As seen by the Democrats in particular, allocation of electoral votes by state resulted in discrimination against the nationwide popular will. Swing states received excessive attention, while candidates visited states known to be reliably Republican or Democratic were visited mostly for fundraisers.

Advocates for a different approach, with different results, argued that the majority of voters rather than 538 electors should select the president. A Constitutional amendment could eliminate the Electoral College, and declare that the candidate with the greatest number of popular votes nationwide should be declared the winner.

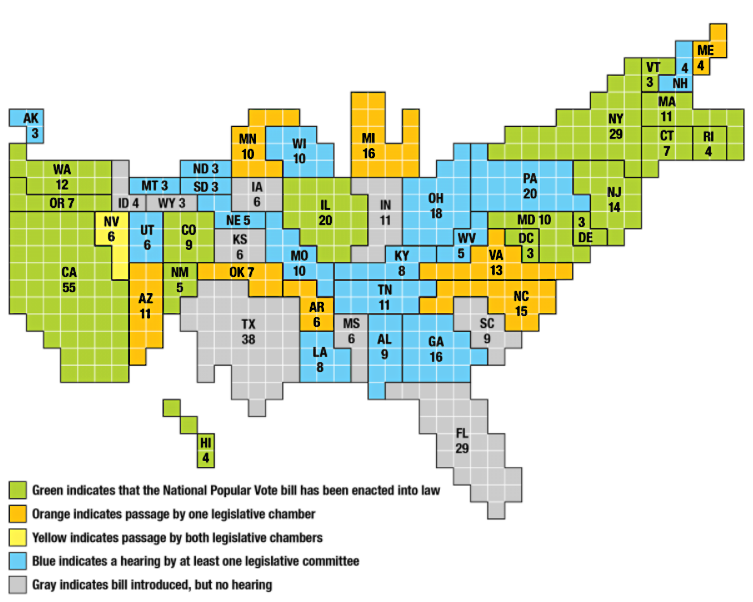

There was no expectation that a constitutional amendment would be approved by the 2/3 of the members in each house of the US Congress and ratified by 3/4 of the states to eliminate the Electoral College, so an alternative approach has been proposed. A National Popular Vote bill ("Agreement Among the States to Elect the President by National Popular Vote") could be adopted by states with at least a majority of 270 electoral votes. Through the agreement, the states would individually direct their electors to support whichever candidate won a majority of the popular vote at a national level.

By the end of 2020, 15 states and the District of Columbia had approved the bill. In states with an additional 88 electoral votes, at least one chamber of the legislature had approved it. States with 74 more electoral votes would have to adopt the National Popular Vote bill before presidential elections would be determined by just the popular vote.

At that point, the Electoral College would become irrelevant without a constitutional amendment. Because each state had individually approved the Agreement Among the States to Elect the President by National Popular Vote, there would be no opportunity for the US Congress to approve or reject it as an interstate compact. In 2020, the Virginia General Assembly rejected a proposal to approve the National Popular Vote bill. The House of Delegates approved it, but the proposal was rejected in the State Senate.16

in 2020, states with 74 more electoral votes still had to approve the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact for it to go into effect

Source: National Popular Vote, Status of National Popular Vote Bill in Each State

Bypassing the Electoral College would result in some electors dismissing the popular vote within their particular state. Instead of being consistent with the will of the voters within their state, some electors would vote for the candidate who had won the greatest number of votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

The National Popular Vote bill would award all of a state's electoral votes to one candidate. Another option is to allocate votes based on the percentage won by each candidate. Under that approach, third party candidates are more likely to win a few electoral votes. If that had been used in 2016, two third-party candidates would have won three electoral votes. Hillary Clinton would have ended up with 268 votes, and Donald Trump with 267. Neither earned a majority (270) votes. The revised process could kick such results to the House of Representatives for a final decision. The process could allow for a decision based on the plurality of votes - so a person who won a minority of popular votes and a minority of electoral votes could become President.

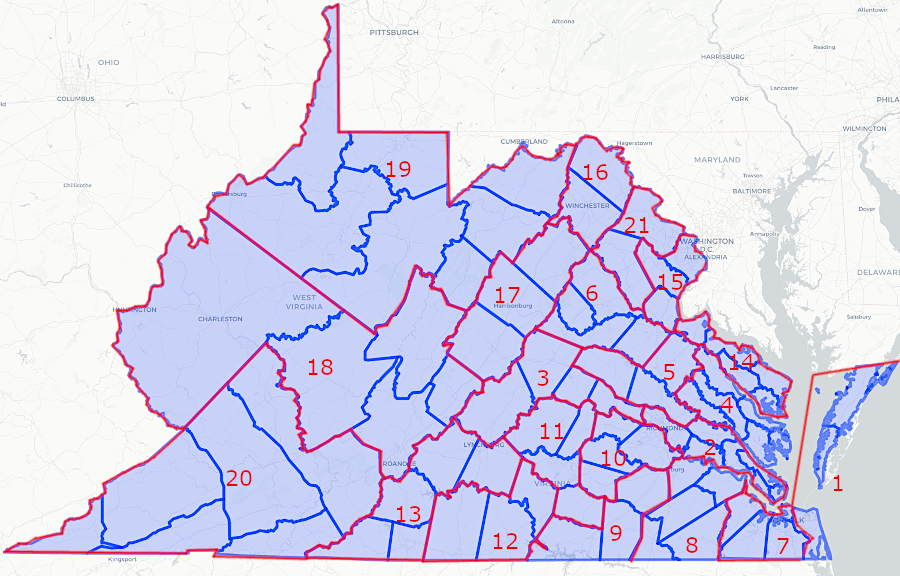

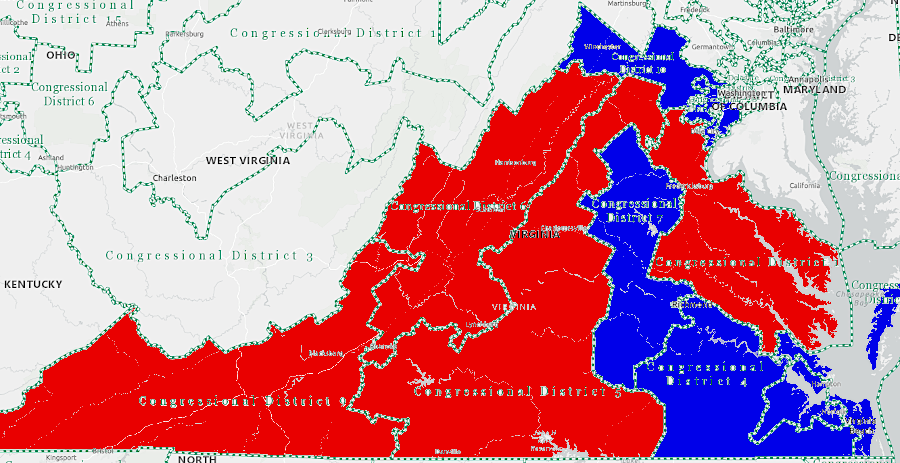

Another alternative to the Electoral College is a "proportional results" system. That could be implemented by using the process in place in Nebraska and Maine. Every state could allocate electors based on the winner in each separate district drawn for electing members to the House of Representatives, and award the two remaining electors based on statewide totals. In 2020, Donald Trump would have won four electoral votes and Joe Biden would have earned just nine in Virginia, rather than the winner-take-all total of 13 votes.

Proportional results based on Congressional district would amplify the incentive to engage in partisan redistricting. In the Seventh District in 2020, Biden defeated Trump by just 49.63%-48.53%

in 2020, allocating electoral votes by Congressional district would have given Donald Trump four votes in Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Map

Another option would require a second, run-off election between the top two candidates if no one gained a majority of popular votes, or of electoral votes. Yet another possibility would be to adopt the parliamentary system used in England, where the party with the majority of members in the House of Representatives would choose the President.

A more-radical proposal to determine who would serve as President was suggested after the 2020 election by Virginia State Senator Amanda Chase, a candidate for the Republican nomination to run for governor in 2021. She suggested using force to ensure her preferred candidate who had been defeated in the 2020 election would remain in office:17

The Trump campaign in 2020 engaged in a last-ditch effort after losing in both the popular vote and in the Electoral College. The incumbent president refused to concede that he lost, and sought to block states from certifying their results with the 35 days established as the "safe harbor" by the 1887 Electoral Count Act.

President Trump also sought to overturn the election results by having state legislatures appoint a new slate of electors or to direct existing electors how to vote.

At the time, however, no state had passed any law authorizing their legislature to ignore the decision of the voters on Election Day and substitute the legislature's preference instead. The only mechanism at the state level would have been to claim the 2020 election had "failed" as defined in the Electoral Count Act of 1887, due to illegal voting or corrupted vote counting machines.

That 1887 law incorporated a provision first passed in 1845 in the Presidential Election Day Act, when the US Congress established a standard day for presidential elections. At the time, states were allowed to set their own date for choosing electors, so long as it was within a 34-day window preceding the first Wednesday in December. That enabled a form of voter fraud known as "pipe-lining" when people who had voted in one state were brought to another state to vote again.

Pipe-lining was particularly egregious in the 1840 election, leading to the adoption in 1845 of a national standard for Election Day. New Hampshire required candidates to get a majority of votes rather than just a plurality, and at times a second vote was required. In Virginia, sheriffs conducted elections in which voters called out their choices. The "viva voce" process was difficult if the weather was harsh or roads were muddy, so poll books might be kept open for a second day to ensure all voters could get to the courthouse. The 1845 law and then the 1877 law allowed states to establish procedures for appointing electors if the process on Election Day "failed."

In 2020, President Trump hoped Republican-controlled legislatures, in states which had voted for Joe Biden, would claim the right to declare a "failed" election and send a Republican slate of electors to the president of the US Senate. Trump also hoped both houses of Congress would accept the slate submitted by legislatures, and reject the slate elected by voters.

No legislature acted on that suggestion. Trump tweeted angrily at the Georgia Governor and Secretary of State, but the two Republicans continued to affirm that the vote was fair and accurate in their state. On December 14, the day for electors to meet in 2020, the Republican slate of electors cast purely ceremonial votes for Trump in a small room in the state Capitol. The official electors met in the Senate chamber and cast 16 official electoral votes for the Democratic candidate, since Joe Biden had won Georgia in the election.

That technique had worked in 1960. Both Republican and Democratic electors in Hawaii voted that year. The recount switched results so Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy ended up winning in Hawaii. It mattered that the "losing" side had submitted its results, so the president of the Senate could count them in 1961.

In Michigan, the Republican electors appeared at the state capitol building prepared to cast their votes for Donald Trump even though Joe Biden had received the most votes in that state in 2020. Law enforcement officials turned them away from the capitol complex, which was locked down to ensure the safety of the 16 members in the Electoral College there.

In Arizona, a group of Republicans submitted an unofficial (fake) slate of electors to the National Archives casting Arizona's 11 votes for Trump. The official Arizona electors met that year in an undisclosed location for extra security, while the fake group tried to assert Joe Biden's victory was illegitimate and submit fraudulent material to Federal officials:18

political party leaders choose electors that will support the party candidates and not be "faithless" voters

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Party Certification of Presidential Primary Candidates (ELECT-542)

The US Congress has not been consistent in defining what constitutes a "majority" of electoral votes. When a Kentucky elector could not travel in time to the meeting of electors in 1808 and vote for James Madison, the state submitted seven rather than eight votes. Congress acted as if there were only 175 rather than 176 total electoral votes, and only 88 rather than 89 were required to have a majority. Madison received 122 electoral votes, so the issue was not treated as significant.

The math used in 1809 to determine a majority of electoral votes was repeated in 1813, when only seven of the eight authorized electoral votes were received from Ohio. Congress dropped the "majority" from 110 to 109 votes, a difference which had no impact on the re-election of James Madison. A similar approach was taken in 1816, when three Maryland electors and one from Delaware did not vote. Congress reduced the total required to claim a majority in 1816 from 111 to 109, and James Monroe became the fourth Virginian to serve as President.

The math used in 1820 for Monroe's re-election in not clear. Three electors died before casting their votes. The National Archives records the whole number of electoral votes in 1820 as 235 and the required majority as 118 votes, but the joint session of Congress recorded only 232 votes actually cast.

During the Civil War and Reconstruction, 11 Southern states did not submit electoral votes to the US Congress in 1864 and three submitted no votes in 1868. However, there was no need to determine if the majority required for election was reduced to the majority of the states which did submit votes in 1864. Abraham Lincoln won 212 electoral votes, so he earned a majority even if the missing 88 electoral votes from 11 southern states were calculated. Similarly, Ulysses S. Grant earned 214 electoral votes in 1868, so there was no debate about requiring the House of Representatives to choose the President because someone could claim that no candidate had earned a majority.

Virginia was divided into two states in 1863, so the western portion of what was Virginia in 1860 was able to submit electoral votes. Five electoral votes from West Virginia were counted in both 1864 and 1868.19

The first objection to counting a state's electoral votes was in 1817. The concern was whether Indiana had completed every step necessary to qualify as a state, and thus qualify to submit electoral votes. The same issue rose again in 1821 regarding Missouri's status as a state. Congress chose to count the votes, knowing they would not affect the outcome of the election. When the status of Michigan was unclear during the electoral vote count in 1837, Congress chose to create an "alternative" list of vote totals and to count Michigan's votes only if they did not affect the result. Martin Van Buren won 170 votes (counting the three from Michigan), far beyond the 148 required for a majority.

The submission from Wisconsin in 1857 was challenged because electors had not met on the assigned day. A severe snow storm had interfered with travel, and the Wisconsin electors met one day late. The issue could not be reconciled, and Congress never made a decision. The confusion did not affect the results; James Buchanan was the clear winner, whether or not the Wisconsin votes were counted.

In 1869, there were objections to the submission from Louisiana. The legitimacy of the Reconstruction-era government was questioned, but the votes ultimately were accepted. A similar objection to Georgia's votes in the 1868 election was resolved by creating an "alternative" tally, but Ulysses S. Grant won easily so the votes did not affect the decision.

The first time the US Congress rejected an electoral vote was in 1873. Three votes from Georgia for Horace Greeley, who had died before the election, were rejected. All other electors for Greeley cast their votes for other candidates, and those were accepted by the Congress.

Congress also rejects the eight electoral votes submitted by Louisiana and the six submitted by Arkansas. The issue was the legitimacy of the electors and whether the submissions had been properly certified. President Grant was re-elected without those 14 electoral votes. Challenges to eight electoral votes submitted by Mississippi and eight from Texas were rejected by Congress; those votes were counted.20

The Electoral Act of 1887 created a procedure for the US Congress to reject the submission of a report from state electors. A member of the Senate and a member of the House of Representatives can object to whatever the president of the Senate (in 2021, Vice-President Mike Pence) reads at the joint session, then the US Congress would have to determine a state's results. A majority in each house, voting separately after just two hours of time allocated for debate, would have to approve the objection before contested votes would be excluded.

The 1877 law left unclear if rejection of a state's votes would alter the total number of electoral votes a candidate had to win in order to have a "majority." One concern expressed in the debate about the law was that rejection of votes might leave no candidate with a majority of the total, forcing the choice of a president into the House of Representatives. The alternative approach would be to reduce the total required to earn a "majority," if some electoral votes were not counted.

Only twice since 1877 have members of the House and Senate objected to the Certificate of Ascertainment submitted by a state. In 1969, a North Carolina elector pledged to Richard Nixon voted instead for George Wallace. When the result was read in the joint session of Congress, a Democratic Representative and Senator objected. The counting stopped, and the House and Senate then debated separately whether the vote should be rejected.

Advocates for rejection highlighted the need to deter the threat of faithless electors becoming rogue kingmakers. Those opposed to rejection argued that step should be reserved for just cases when Congress received two sets of returns. In the end, the North Carolina slate was accepted by separate votes in each house and the counting of electoral votes resumed.

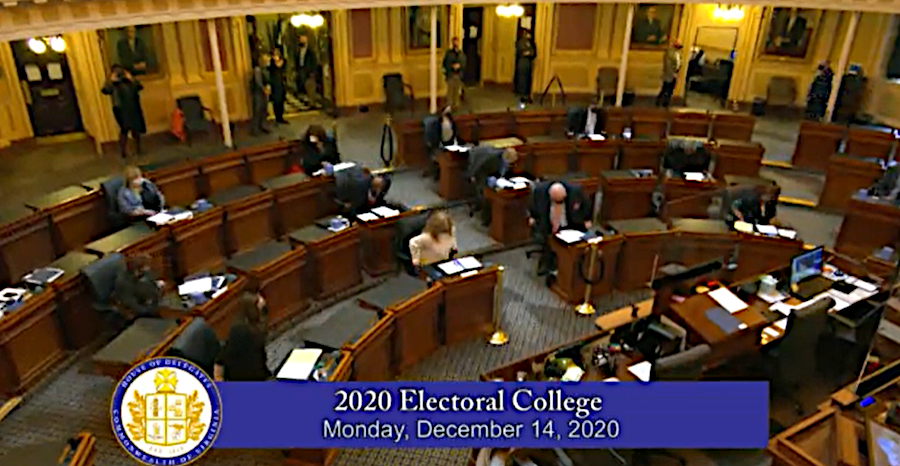

in 2020, Virginia's 13 electors livestreamed their meeting the House of Delegates chamber with no members of the public, due to COVID-19 pandemic

Source: Virginia General Assembly, Virginia Electoral College (December 14, 2020)

One other objection occurred in 2005. A Representative and a Senator who supported Democratic candidate John Kerry challenged the submission from the Ohio electors for re-electing George W. Bush. The objectors highlighted voting irregularities that had been reported, particularly in low-income and African-American neighborhoods. Both houses decided to accept the Certificate of Ascertainment from Ohio, with a 267-31 vote the House and a 74-1 vote in the Senate.21

How President Trump expected to get a majority in the Democratically-controlled House of Representatives to object to the submissions from state electors was unclear.

One possible way to bypass that step was a lawsuit filed by the Texas Attorney General and supported by 126 of the 196 Republicans in the House of Representatives, including all three from Virginia. The suit asked the US Supreme Court to prevent counting the 62 electoral votes from Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan and Wisconsin. If those states were excluded, then Biden's total would drop from 306 to 244. Trump received only 232 votes, but denying Biden a majority (270 votes) would throw the choice of President into the House of Representatives. The US Supreme Court, including three members appointed by Trump, dismissed the lawsuit without a hearing.

In response to Trump's extraordinary efforts to have objections by House and Senate members ultimately overturn the results of the 2020 election, Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) commented:22

in 2021, members of the US House of Representatives and US Senate objected to electoral votes which had been officially submitted by several states, and vote was delayed when Trump supporters stormed the Capitol

Source: Joint Session of US House of Representatives and US Senate (January 6, 2020)

The 1876 election created a precedent, where a commission was chosen to resolve the conflict. The difficulty of resolving the disputed electoral votes in 1876 led to passage of the Electoral Count Act 11 years later. That 1887 law established that states should certify their electoral results according to existing state law.

However, the Electoral Count Act did not prohibit state officials from certifying multiple slates, perhaps after passing a law that would allow substituting their preference and ignoring the votes of a plurality/majority of the voters in their state. Hawaii sent two slates to the president of the Senate in 1960, after a recount changed results and determined John F. Kennedy had won a majority of votes. Vice-President Nixon chose to ignore the Republican slate, and no one contested his decision.23

In 1968, George Wallace ran as an independent candidate and received 46 electoral votes. His goal was to block the Democratic and Republican candidates from getting a majority of electoral votes, then negotiate a deal in the House of Representatives with one of those candidates who would adopt some of Wallace's policies. If Wallace had won Tennessee and Hubert Humphrey had won Ohio, then the strategy would have worked.

The vote of the North Carolina faithless elector for Wallace in 1969, and concerns regarding George Wallace's attempt to create a brokered deal in the House of Representatives, led to action in the US Congress to eliminate the Electoral College. The House of Representatives passed a bill in 1969, 339 to 70, to elect the President and Vice President by direct popular vote. President Nixon endorsed it, and 3/4 of state legislatures were expected to ratify it - but a filibuster by Senators from Southern states killed the bill.

The proposal for election by a plurality of the popular vote was revived in 1979. That time, a majority of Senators approved the bill. However, Constitutional amendments require a supermajority approval by 2/3 vote, and the majority in the Senate fell short. Only once has a Senate supermajority endorsed a change in the Electoral College. In 1950, the Senate approved the Lodge-Gossett Amendment in a 64-27 vote. It would have allocated electoral votes in proportion to the popular votes in each states, but the House of Representatives killed that bill.

When a Virginia convention ratified the US Constitution in 1788, the states had significantly different populations. Virginia, with the largest population, had 12 times the population of Delaware. Today, California has 65 times the population of Wyoming. The impact of giving every state equal representation in the US Senate, and at least three electoral votes, gives smaller states an even greater impact in electing the President and Vice-President.

According to the National Archives:24

the vote of Virginia's electors formally determines the state's winner of the presidential race every four years

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries, Finishing touches (by Charles Henry Sykes, 1940)

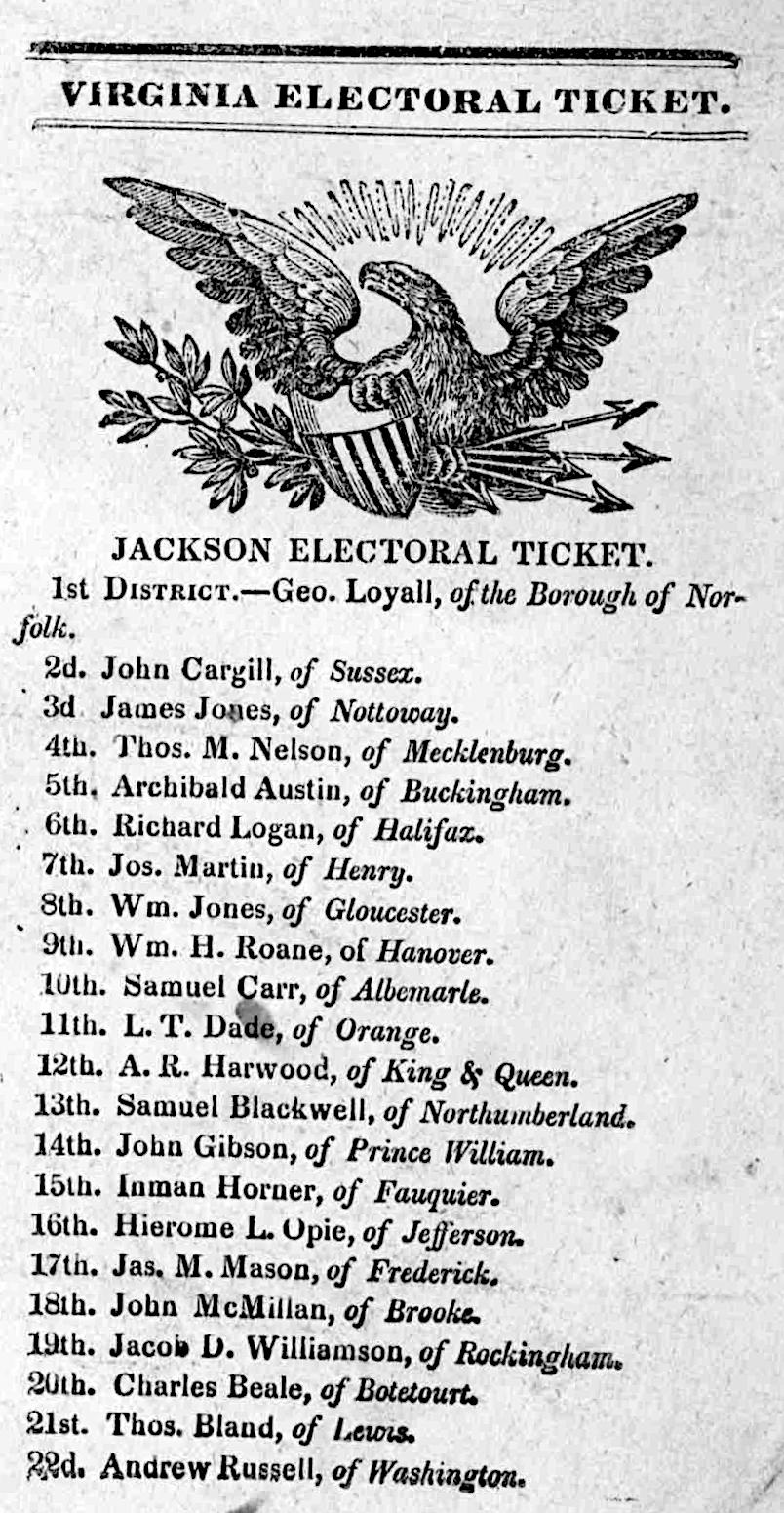

the electoral slate for Andrew Jackson in 1832 had one member from each Congressional district

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia electoral ticket (1832)

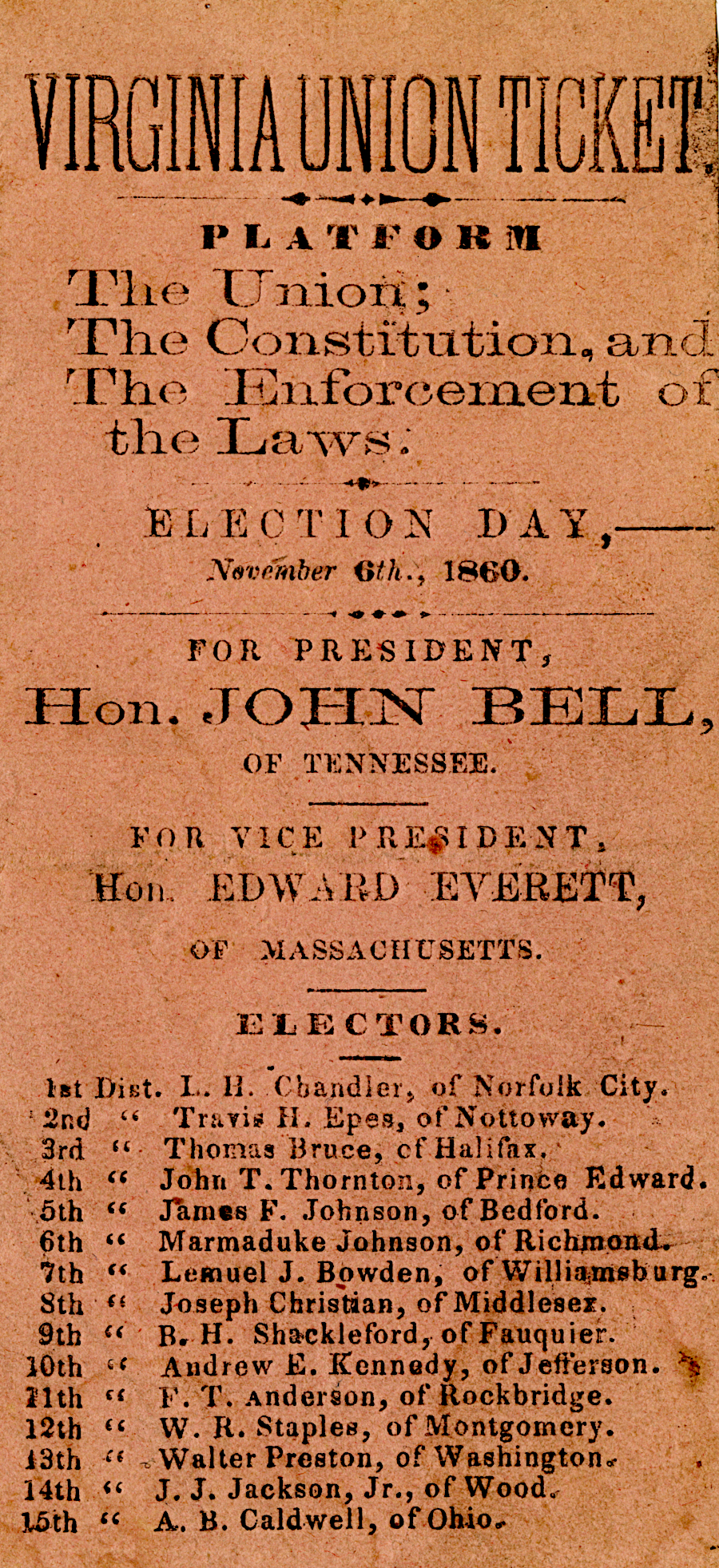

in 1860, Virginia had 15 electoral votes

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Virginia Union Ticket, 1860

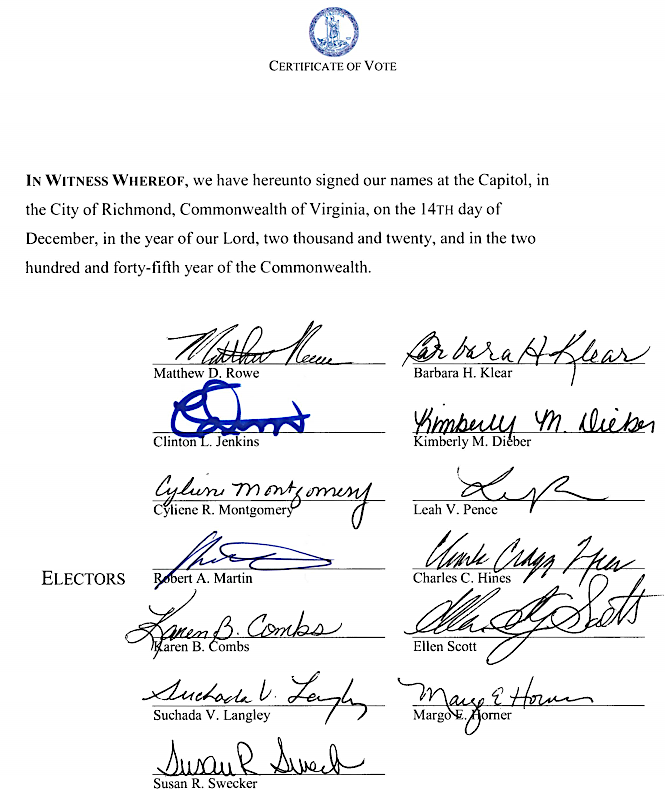

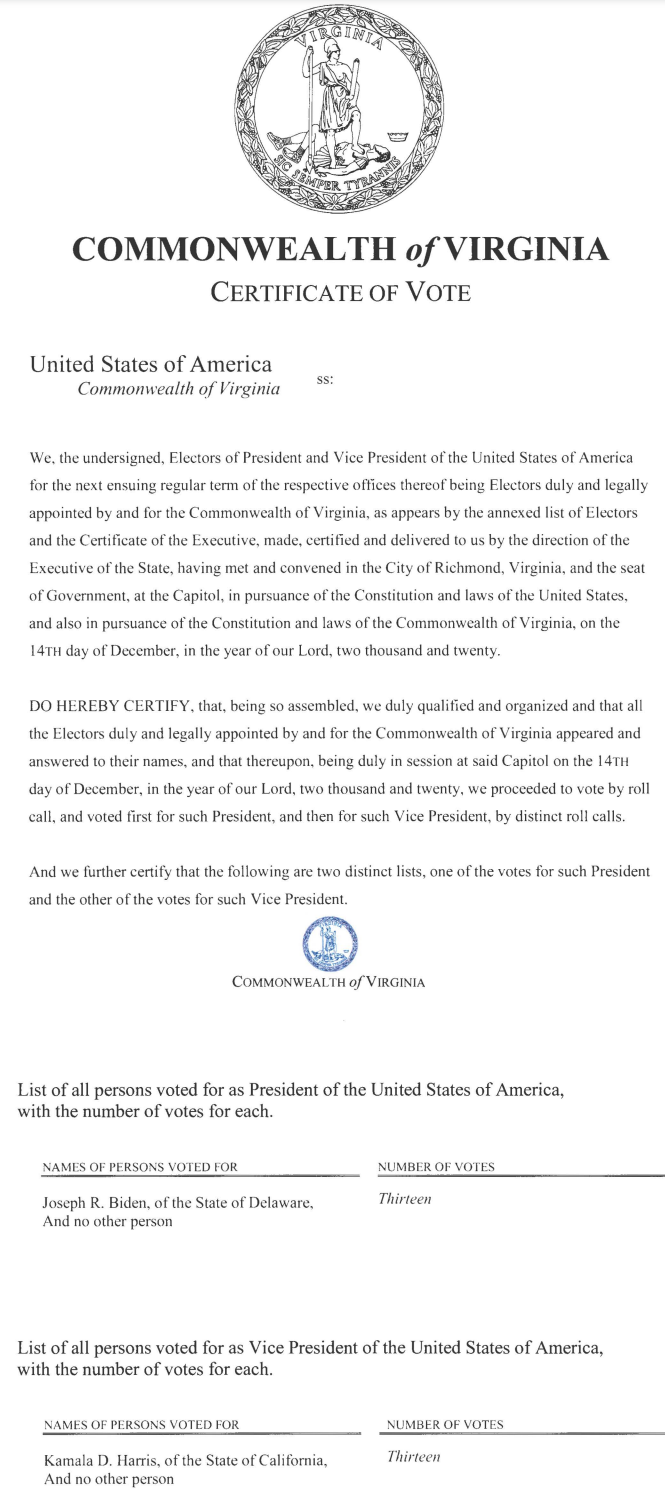

Virginia's 13 electors in 2020 voted for Joseph Biden as President and Kamala Harris as Vice-President

Source: National Archives, 2020 Electoral College Results