I'm Charlie Grymes. Since 1998, I have been building this site. Slowly.

I'm Charlie Grymes. Since 1998, I have been building this site. Slowly.

I'm Charlie Grymes. Since 1998, I have been building this site. Slowly.

I'm Charlie Grymes. Since 1998, I have been building this site. Slowly.

Compiling a new geographic description of Virginia is a fun challenge - but many of the 1,000+ pages on the VirginiaPlaces.org website are far, far, far from finished. If you explore further, expect to find incomplete pages and content that needs to be updated/corrected/terminated with extreme prejudice.

On the maternal side, my relatives come from Halifax County. On my father's side, the Grymes family has been in Virginia since the 1640's. The paternal genealogy is easier to trace, since the last name has an unusual spelling.

Anglican minister Rev. Charles Grymes was caught up in the emerging religious conflicts in England associated with the rise of the Puritans and efforts to repress them by William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury. After my ancestor moved across the Atlantic Ocean, my side of the Grymes family stopped migrating. I am the 10th generation to live in Virginia.

I suspect Rev. Charles Grymes chose to move across the ocean because he was unable to keep his mouth shut. Come on a field trip sometime, and you might recognize the family trait has reappeared.

When Rev. Grymes wanted to get out of England as it veered towards civil war, the obvious place to go was the new colony of Virginia. At the time, Virginia was still a raw and uncomfortable place for new immigrants. All English settlements were located east of the Fall Line. Nearly every structure occupied by colonists was what today would be described as a "wooden shack." Native Americans still controlled most of the land, and no colonist had climbed the Blue Ridge yet.

The Grymes men bought estates back in the 1600's and 1700's, when land was cheap cheap cheap. Colonial law allowed men to dominate family finances and public roles. Various ancestors of mine were influential in the House of Burgesses and on the Governor's Council.

You might think we would be rich landowners today - but no, we have managed to buy high and sell low for generations. In the colonial days, there were family plantation homes scattered around Tidewater, such as Moratico on the Rappahannock River and the mellifluously-named "Grymesby on the Piankatank." They are all gone today.

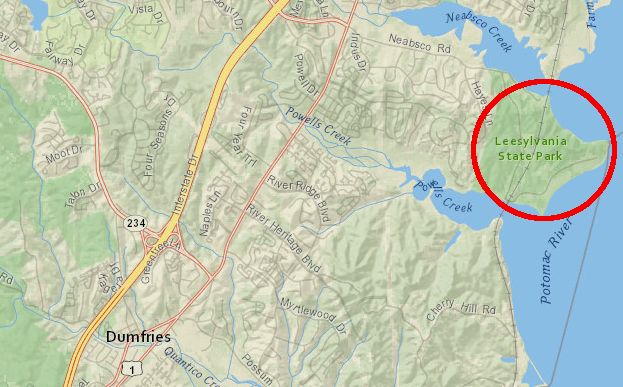

The Grymes women seemed to thrive in Virginia better than the men, in part because the women married well. One, Lucy Ludwell Grymes, was by family tradition the "lowland beauty" that caught George Washington's eye but rejected his advances. Young Mr. Washington was not good enough, or perhaps showed few prospects of obtaining enough wealth to ensure family comfort. Lucy Ludwell Grymes married Henry Lee II instead, and lived on the plantation that is today Leesylvania State Park. She and her husband Henry Lee are buried there.

Lucy Ludwell Grymes chose to live with Henry Lee at Leesylvania, after rejecting young George Washington

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Their first son was Henry "Lighthorse Harry" Lee, a cavalry officer who served General Washington well in the American Revolution. Lee said in his eulogy for Washington the famous lines First in War, First in Peace, and First in the Hearts of His Countrymen.

Unfortunately, young Henry Lee III must have inherited the financial talents of his mother's family. He died bankrupt, after failing to pay debts owed to George Washington (for a purchase of shares in the Dismal Swamp Company) and to many others.

His last son, Robert E. Lee, helped restore some luster to the Lee name as head of the Army of Northern Virginia during what was described into the 1960's as the "late unpleasantness." Just being a grandson of Lucy Ludwell Grymes makes him important to my family. His role in the Civil War is challenged today, but he deserves some respect for his service as president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, from 1865 to his death in 1870.

Not all of my family has been on the right side of peace, justice, and the American Way. One of my many-generations-ago ancestors was the District Attorney in New Orleans. John Randolph Grymes was prosecuting the local pirates until Jean Lafitte went on trial.

That led to an immediate career change. John Grymes ended his role as District Attorney and started a career as a private attorney, defending Jean Lafitte. At least someone in the family once made a little money, at least until the lawyer's fee was spent in Lafitte's local houses of entertainment on wine, women, and song.

My more-respectable, more-dull branch of the Grymes family stayed in Virginia. They migrated to Orange County and then Chesterfield County, before my grandfather settled in Richmond as a grocer.

the skyline of downtown Richmond includes (from left to right) the headquarters of MeadWestvaco Corporation, the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, and office towers housing financial and legal firms

Other branches of the family moved across the Ohio River. One came back to visit as a Union soldier. He wrote about marching with Sherman through Georgia in 1864, saying in a letter that "we enjoyed it hugely." I suspect that the Old Virginia side of the family did not have fond feelings towards him...

I retired in 2007 from a day job pushing paper as a Federal bureaucrat in a Washington, DC office. Before retiring, I became adjunct faculty at George Mason, teaching for the fun of it.

In my earlier days, I have laid railroad track in Richmond, shipped tobacco from auction warehouses and packed it into hogsheads in Florida/North Carolina/Kentucky, led cave tours and presented campfire talks as a National Park Service ranger in Missouri, and managed scenic easements on a Wild and Scenic River in Oregon for the Bureau of Land Management.

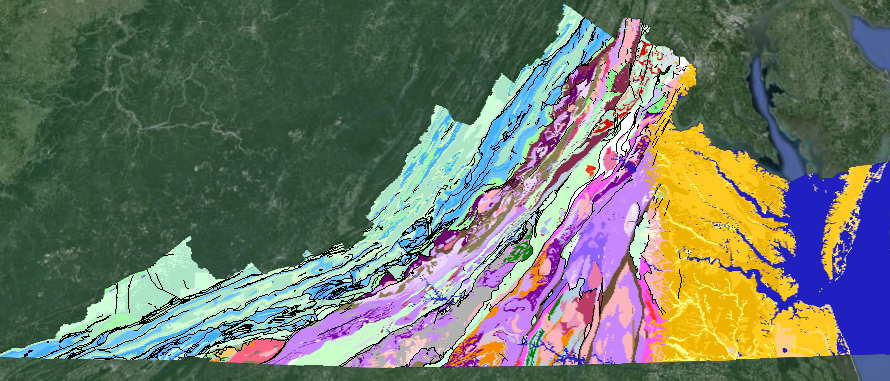

sediments from the Shenandoah Valley end up, after rainstorms, east of I-95

Source: Google Earth

I spent the last 20 years of my career working on information technology projects for the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the Department of the Interior. On a good day, I facilitated adoption of Geographic Information System (GIS) technology and crafted the initial policy and procedures as we implemented e-mail, websites, and other internet-based capabilities. Today, I am active in local history and environmental groups in Prince William County.

I taught the "Geography of Virginia" class at George Mason University as an adjunct instructor for about 15 years, starting in 1999. In addition to "Geography of Virginia," at various times I have taught field study classes ("Virginia From the Ground Up - Northern Virginia/Southwest Virginia/Shenandoah Valley"), plus courses involving communications and natural science in what was called New Century College at GMU.

My qualifications were mostly my curiosity, my willingness to research whatever I found interesting, and my knowledge from living in Virginia for six decades. There are places within the state that I have not visited in person... but few of them.

I checked off the "visited every county" list when I finally got to Gwynn's Island in Mathews County. That's where one ancestor had provided shelter to Lord Dunmore at he start of the American Revolution. The royal governor had fled Williamsburg in 1775. Dunmore was enjoying the hospitality on my relative's plantation, accompanied by sailors and marines from several British warships and an army recruited from Virginia loyalists and formally-enslaved people. When the 3rd Virginia Regiment appeared and artillery arrived from Gloucester, Dunmore - and my relative - had the good sense to sail away to New York City.

My academic credentials: I earned an "independent studies" diploma from the University of Virginia in 1975. I never chose a formal program of study, since as an Echols Scholar I did not have to declare a major. I was fortunate to find high-quality instructors who allowed me to do field research as independent study projects, rather than sit in a classroom listening to standard lectures.

I finished my Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS) degree at GMU in June, 2002. My MAIS project was an examination of the cultural and natural history of Prince William County in Northern Virginia. I earned two degrees, but never chose a major field of study that fit into the typical academic pattern. I chose not to pursue a PhD, but instead to continue my learning on independent tracks. Because I lack a terminal degree in the subject, in academic settings I do not describe myself as a "real" geographer.

I have been poking into the famous and unknown places of Virginia for decades. I find the challenge of understanding how places change over time to be fascinating. The idea that the sand grains on Virginia Beach could have come from Massanutten Mountain near Harrisonburg still intrigues me. When the thunderstorms of summer roll through, you'll find me in the cheering section rooting for another flash and bang in the sky, and wondering if erosion will expose new fossils in certain stream channels.

When the cardinal flowers appear in the wetlands in August, I know that those thunderstorms of summer are almost done. When ice and snow arrive, I grouse about the cold and burn firewood to keep warm, just like my ancestors did.

Studying the electrical grid and the pattern of oil/gas pipelines is entertaining, but experience is the best teacher. When a hurricane or at least a nor'easter arrives, I know the electricity could be cut off. A prediction of a heavy snowstorm means it is time fill up the bathtub with water.

I live in a house that is not connected to a municipal water system. When you depend on a well, the loss of electrical power means the loss of water too. Experience has taught those of us living on well-and-septic to stockpile gallon jugs of water in the crawl space, n order to flush a toilet when the water pump has no electricity. Knowing about infrastructure across the state is less important than having a reliable water supply within the house.

The patterns of people in Virginia intrigue me as much as the natural history. Folks in Southside really are different from people in Arlington, and the diversity of culture is not limited to just Virginia's urban areas. Across Virginia, we may all watch the same TV commercials (one reason our regional accents are fading), but we are not fully homogenized yet. On Monday mornings, you will find people talking about the latest NASCAR events in Pittsylvania County - but in Loudoun, discussion at the water cooler is more likely to be "think the Caps can win the Stanley Cup this year?" In Roanoke, sports talk focuses on football success at Virginia Tech more than basketball championships at UVA. (No one talks about football success at UVA; it appears some traditions are just unbreakable.)

The study of Virginia helps me understand why we have such differences. Geography, both physical and cultural, is more challenging than reading a detective story. It is also more fun to unravel. Different places evolved along different paths for different reasons, and connecting the dots can create a great picture of Virginia.

There are links between places that require both a scientific and historical perspective. Price Mountain coal was squeezed hard enough by the collision with Africa about 300 million years ago to become semi-anthracite coal. That is why fuel from near Blacksburg might have been used in 1862 to power the Civil War ironclad CSS Virginia when it fought the USS Monitor in Hampton Roads.

Virginia is a special place, worth exploring in depth. Getting stuck in traffic provides unplanned research opportunities to look outside the car window and ask "why does it looks like that, at this particular place?"

Erosion from fields created for growing tobacco, and from converting the forest into charcoal for the Neabsco Iron Furnace, caused the once-bustling port of Dumfries to become a backwater Today the mud-filled estuary of Quantico Creek is a natural resource wetland.

Prince William Forest Park has the cleanest natural water in Northern Virginia - though at one point, a pyrite mine poisoned it with acid runoff and heavy metals. The National Park Service reclaimed the mine site and Quantico Creek is healthy... but the historically interesting mining shafts are now completely obscured by an oh-so-boring stand of loblolly pine trees. The Federal agency examined the full range of "what happened here, what makes this place special" before deciding to replace history with nature.

Completion of the Shirley Highway from the Pentagon to the Occoquan River in 1950 triggered the construction of Marumsco Hills subdivision in Prince William County, followed by Lake Ridge, Dale City, Montclair, etc. Suburban sprawl in Northern Virginia still follows transportation corridors. In the near future, watch the Metrorail's Silver Line spur new subdivisions in Loudoun County, and how office buildings that are not located on bus/rail transit routes struggle to find renters.

When I started teaching "Geography of Virginia", regional geography classes at universities were being replaced by GIS courses that offered much greater job potential to students. The most recent textbook on the topic was 50 years old. There was dry, academic material about crops and capitals, plus a lot of historical information shaped heavily by outdated political attitudes.

To hold the interest of students and to keep from being bored myself by facts and data, I needed a textbook that told stories about places. My personal style is to learn from the specific to the general, to examine a specific place first and then discover the general causes and patterns that shaped that place. Central place theory, environmental determinism, and other fundamental Geography 101 concepts "come alive" when I can relate them to actual places.

To justify giving academic credit at the college level, I wanted students to be able to explain the "why of where" - why places in Virginia were different, and what had caused those differences. To me, the most interesting geography stories illustrate how physical and cultural patterns are related. People from the first Native Americans to the most recent immigrant have applied their geographic expertise when they chose where to live and work.

I wanted my students to be able to make better choices in real life after a semester, rather than just identify the top agricultural products and manufacturing regions. My goal was for the content to be relevant to modern-day decisionmaking, to provide context for real life choices rather than be completely forgotten after the final exam. Ideally, students would be more informed when deciding how far to commute for a job, or expressing a political opinion involving a Virgina-related issue.

So I developed the VirginiaPlaces.org website to serve as the missing textbook.

The content is based on personal experiences as well as re-packaging of much material published by others, which is cited in footnotes. There is a lot of "history" mixed in with the "geography." History is what happened at places, and geography is the places where stuff happened. Telling stories require setting the stage as well as action by characters.

George Mason University oversight of the content which I taught was light; I was fortunate to have a free hand to develop 15 weeks of material. I consciously highlighted topics which I thought were under-taught in other classes, and made the material as interdisciplinary as possible. Environment and history were taught to me as isolated topics with minimal relationship to each other outside of Civil War battles, so I incorporated environmental science whenever possible.

The toughest challenge was trying to make geology relevant to students who signed up for a regional geography class, and more than just a memorize-regurgitate-forget segment. Converting jargon-filled publication data into "why are we looking at a hill instead of a flat eroded plain, why did gold form here, and why is this pebble round" stories was tough. I was, at best, only partially successful at slipping geology material into different weeks in the semester. Watershed management was far easier to incorporate.

Even after 15 years of teaching, it was always a challenge to offer a little information in order to trigger enough curiosity to get students to ask questions, and only then tell "why" stories. Field visits were far more intellectually stimulating than my pontifications in a classroom.

This website attempts to describe some of the story of Virginia places. There is no paywall; feel free to browse. References are cited, but the interpretations and the mistakes are mine. Material is available for reuse under Creative Commons license, but double-check for permission if there is a link/footnote citing an original source. Don't be surprised if you find errors of fact and interpretation. Some of the material is 25 years old and needs to be refreshed.

Welcome. Explore. Enjoy.

Questions/comments? Contact me via e-mail at ![]()

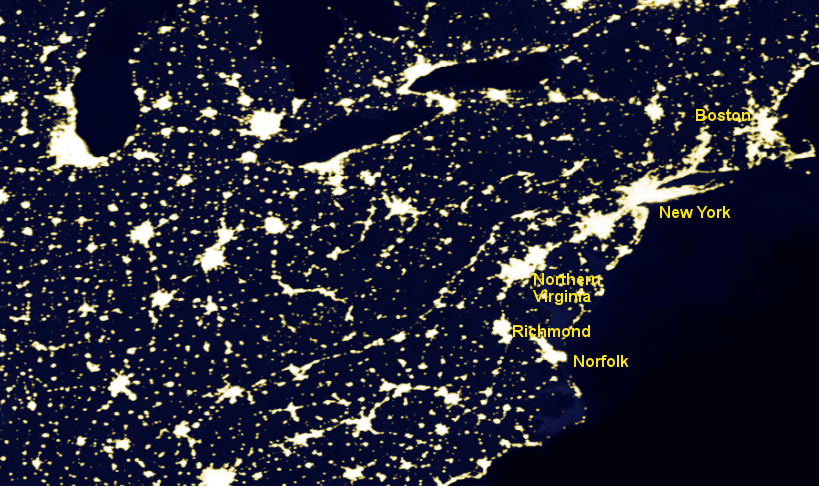

Virginia's largest urban areas are an extension of the Boston-Washington corridor

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Visible Earth