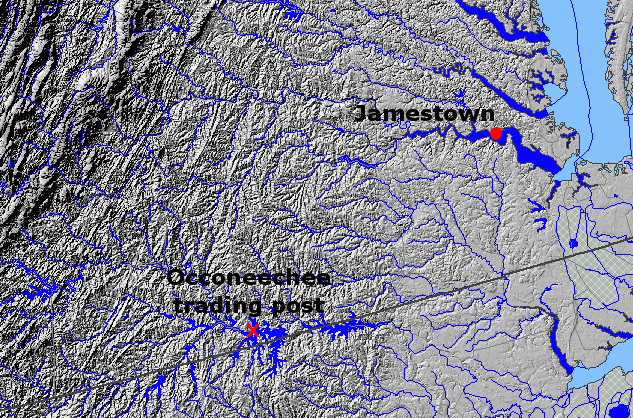

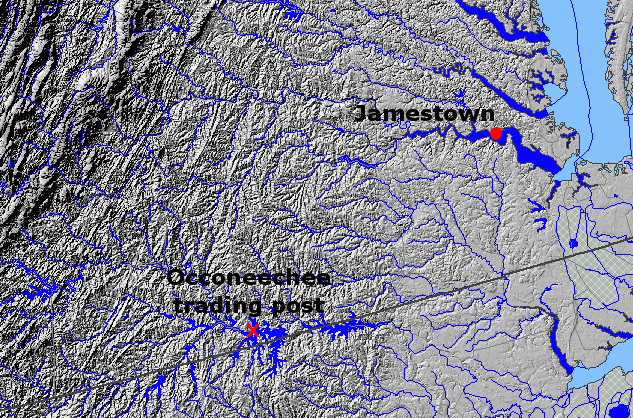

Occaneechi fur trading post, on the Roanoke River (now Kerr Reservoir)

Source: USGS National Atlas

Occaneechi fur trading post, on the Roanoke River (now Kerr Reservoir)

Source: USGS National Atlas

At times the English chose to acquire land in Virginia through force that displaced the Native Americans, and at times the colonial leaders preferred negotiations. In the General Assembly and in the taverns, colonists often debated the appropriate strategy. In 1676, that debate erupted into civil war in Virginia.

In 1675, there was a conflict between an overseer in Stafford County and members of the Moyumpse (Dogue) tribe over some hogs and payment for items acquired by the overseer. The overseer was killed, and the Native Americans fled across the Potomac River back into Maryland.

The Virginia colonists crossed into Maryland on a retaliatory raid. The colonists killed innocent Susquehannocks (not Dogues) despite the promise of a flag of truce. The Susquehannocks moved into Virginia and responded by attacking the homes of colonists on the edge of Anglo-Native American settlement (the "frontier").3

The conflict led to Bacon's Rebellion, a civil war among the Virginians that was fueled by the frontier settlers' frustration with Governor Berkeley's frontier policies. The colonists expanding into traditionally Native American spaces on the northern and western edge of the colony (such as Stafford County) were already struggling with low tobacco prices and high taxes. Frustration was exacerbated by the powerful gentry in Jamestown exempting themselves from paying those high taxes, adding to the burden of the small farmers.

The reluctance of Governor Berkeley and his wealthy councilors to provide military protection against attack by Moyumpse (Dogue), Susquehannocks, or Iroquois caused the struggling farmers on the frontier to rebel. As described by one of Virginia's first historians, Robert Beverley:4

The "splitting of the colonies into proprietaries" referred to the 1663 land grant by Charles II that ended up as North Carolina, plus the 1649 grant o seven supporters tha later was known as the Fairfax Grant. The Fairfax grant excluded the colonial government in Jamestown from issuing patents (land grants) for property between the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers, the Northern Neck, just as the colonial population was increasing enough to spur settlement north of the Rappahannock River.

By the 1670's, land adjacent to a navigable river connecting to the Chesapeake Bay was getting scarce. Virginia colonists were not happy at the prospect of having to move west of the Fall Line in order to obtain cheap land south of the Rappahannock River. There were no wagon roads at the time, so on properties wes of he Fall Line the cost to haul tobacco to a wharf for export was high compared to waterfront property.

The "heavy Restraints and Burdens laid upon their Trade by Act of Parliament in England" referred to the Navigation Acts, limiting tobacco sales to non-English buyers. Limiting sales to English merchants, thus reducing competition from the Dutch and others, led to lower tobacco prices paid to Virginians. Virginia colonists also objected to efforts to impose taxes that would be used simply to pay additional money to the tax collectors, which caused the tax collectors to support the governor and his cronies but created no benefits for most colonists.

The "Disturbance given by the Indians" was a one-sided description of the conflict caused by settlers moving into the territories long occupied by the Algonquian-speaking tribes north of the York River. The attacks by Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannocks on the Virginia and Maryland frontier in 1676 were triggered by the Anglo-Dutch war, manipulation of the Susquehannock populations by Maryland colonial officials, and retaliation-without-distinction policies of Virginia colonial officials. Similar "disturbances" in New England erupted in King Philip's War in 1675, between the Wampanoag/Narragansett/allied tribes and Massachusetts/Rhode Island/Connecticut settlers.

Governor Berkeley opened his jacket and challenged Nathaniel Bacon: "Here shoot me before God, fair mark shoot"

Source: National Park Service Sidney King painting, Nathaniel Bacon confronts Governor Sir William Berkeley

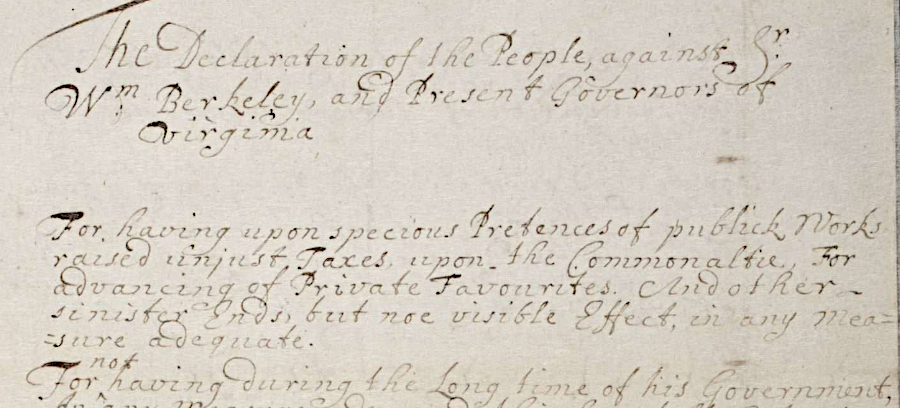

Nathaniel Bacon, a new immigrant from England who was not caught up deeply in the web of social alliances in Tidewater, published the "Declaration of the People of Virginia" on July 30, 1676. He demanded a military commission that would authorize him to attack Indians on the frontier.

Nathaniel Bacon, a member of the Virginia elite, ended up as a rebel

Source: Library of Congress Nathaniel Bacon engraving by T. Chambars

Bacon was a member of the gentry (the "elite" with political and economic power in the colony). Bacon and Berkeley negotiated unsuccessfully for an official colonial war to remove Native Americans from the frontier. Bacon finally instigated open conflict. His rebels burned the colonial capital of Jamestown, pillaged the houses of Berkeley's rich allies, and forced the governor to flee to the Eastern Shore.

Nathaniel Bacon's Declaration of the People of Virginia was issued on July 30, 1676

Source: Encyclopedia Virginia, Nathaniel Bacon's Declaration of Grievances (provided by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

In a dramatic confrontation at the statehouse in Jamestown, Bacon threatened to shoot the governor unless he provided official commissions for Bacon's rebel army. Berkeley responded boldly "Here shoot me before God, fair mark shoot."5

When Bacon threatened to conduct military operations against the Native Americans without authorization, Berkeley declared him a rebel. The response was a public wave of support for Bacon, reflecting discontent over the economic recession at the time as much as concerns about Native Americans.

The public response frightened Berkeley enough to force him to schedule an election for a new House of Burgesses. Bacon was elected, and Berkeley let him take his seat on the Governor's Council of State. However, Bacon quickly left Jamestown, rallied a mob, and attacked innocent Occaneechi, Tutelo, and Saponi Indians at their trading base at modern-day Clarksville at the confluence of the Dan and the Roanoke (Staunton) River.

Bacon forced the Occaneechi to surrender Susquehannocks that Bacon claimed were responsible for "outrages" on frontier farms. Bacon's forces then destroyed the Occaneechi village - even though the Native Americans there had done nothing to threaten frontier settlers. Destruction of Occaneechi Town would disrupt Berkeley's control of the fur trade, weakening him personally and perhaps creating some opportunity for others living on the frontier to make profits through trade.

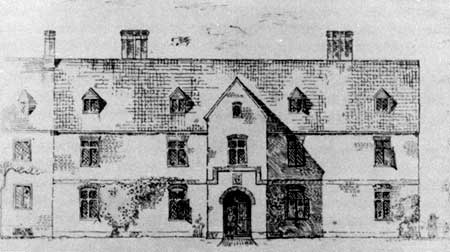

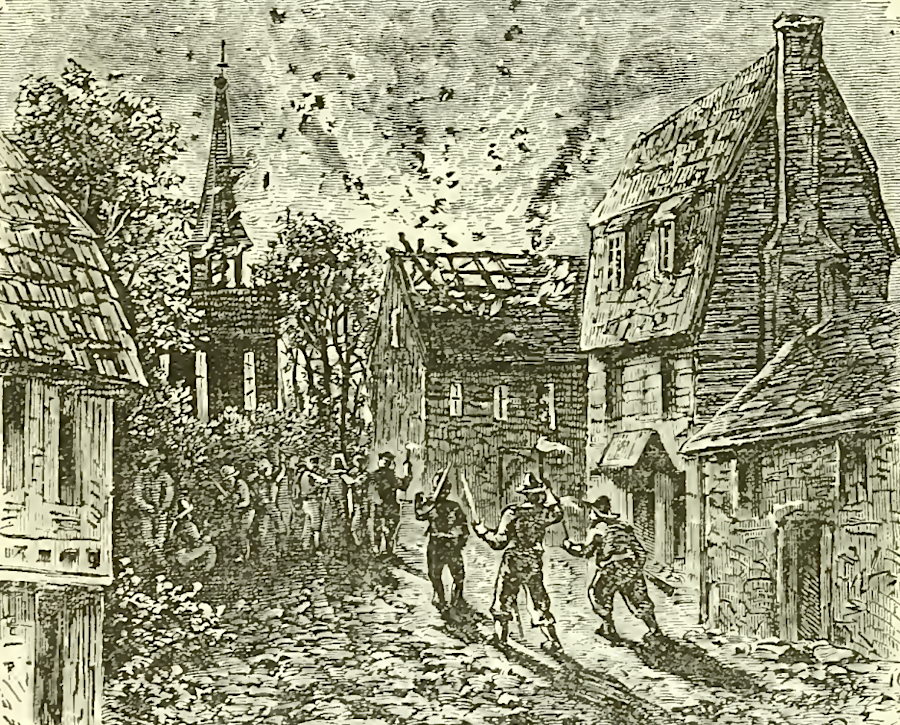

Bacon marched his small army back to the capital where the House of Burgesses, intimidated by the mob, passed legislation demanded by Bacon. Bacon burned Jamestown, including the statehouse, and plundered the plantation homes of the gentry who supported Governor Berkeley.

third statehouse at Jamestown, burned in Bacon's Rebellion

Source: National Park Service, America's Oldest Legislative Assembly and Its Jamestown Statehouse

The governor fled Jamestown and went to John Custis's Arlington plantation in Northampton County, on the Eastern Shore. When Bacon sent a flotilla to attack Berkeley in his last refuge, the governor's forces surprised and captured it. Berkeley sailed back to the west side of the Chesapeake Bay, captured many of the rebels after Bacon died of a "bloody flux," and proceeded to execute many of the top rebel leaders. (Berkeley's harsh response may have been spurred in part by laws that allowed him to seize the wealth of the rebels.)

Among Bacon's rebellious allies was William Drummond, a member of the gentry and a personal enemy of Berkeley. Drummond had been governor of North Carolina (Lake Drummond is named for him). After Drummond was captured, Berkeley greeted him with a malicious "Mr. Drumond! you are very welcome, I am more Glad to See you, than any man in Virginia, Mr. Drumond you shall be hang'd in half an hour." In fact, Drummond's trial did not occur until six days later, but he was hung within several hours of his conviction.6

The officials in London did not support the vindictive retaliation. Charles II is reported to have been surprised at Berkeley's executions, saying "That old fool has hanged more men in that naked country than I have done here for the murder of my father." Charles recalled Berkeley to England, where the governor died.7

To avoid capture by Nathaniel Bacon's army, Governor Berkeley fled from Jamestown to the original Arlington Plantation, owned by John Custis in Northampton County (route in red). In 1676 the British officials appointed by King Charles II ended up defeating the rebellious colonists. A century later, Lord Dunmore fled Williamsburg at the start of the American Revolution, to attack Norfolk and then to his final base at Gwynn's Island (route in yellow).

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service Wetlands Mapper

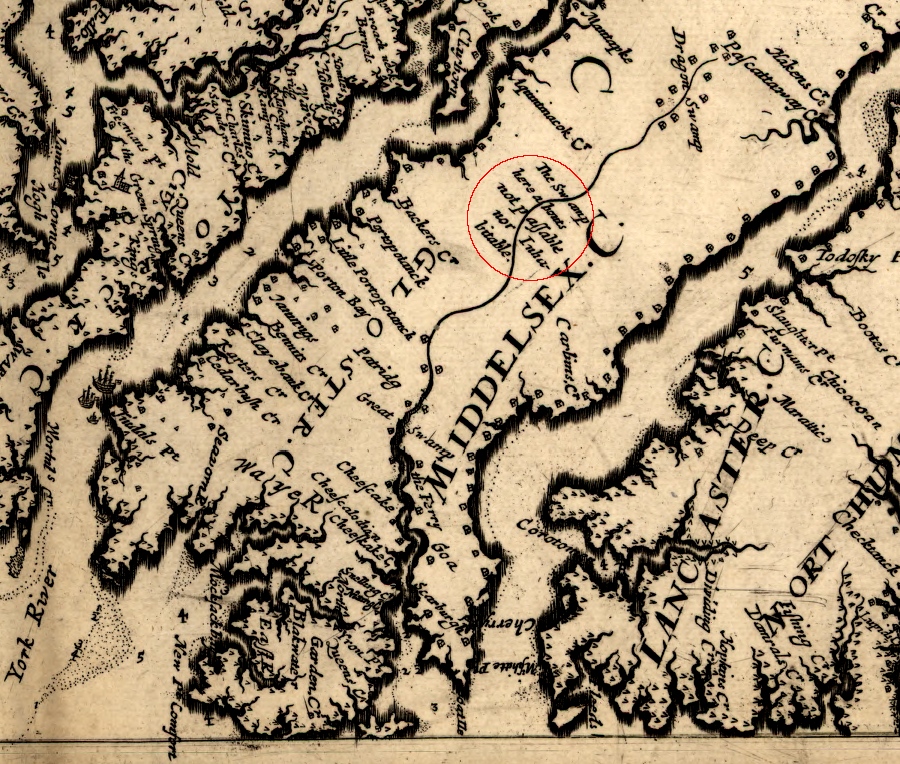

Bacon's rebels initially targeted Moyumpse (Dogue) and Susquehannock living in northern Virginia. Innocent victims in 1676 included the Pamunkey tribe. They were nearby, and the rebels were indiscriminate in their attacks. The Pamunkey escaped by fleeing into the swamps near the headwaters of the York River.

The equally-innocent Occaneechi tribe, southwest of Fort Henry (modern-day Petersburg) on the trading routes for furs, was less fortunate. Their trading post at modern-day Clarksville, Virginia was destroyed, shrinking their role as the middlemen in the trade between the English forts on the Fall Line and the backcountry in the Roanoke River and even Tennessee River watersheds.

to escape Bacon's troops in 1676, the Pamunkey retreated into the swamps along the Piankatank River, which a 1670 map described as "not passable nor inhabitable"

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman, with north oriented to the right rather than towards the top of the map)

Bacon's Rebellion was followed by the Treaty of Middle Plantation in 1677 with the Pamunkey, who were attacked by Bacon even though the tribes were theoretically under English protection since the Treaty of 1646. In 1677, the "Queen of Pamunkey" (Cockacoeske) was granted a reservation in King William County, establishing the legal basis for today's Pamunkey and Mattaponi reservations. Tribes that had not been part of Powhatan's paramount chiefdom also signed the treaty, including the Iroquoian-speaking Meherrin and Nottoway and the Siouan-speaking Saponi.8

Because the Iroquois were mobile, crossing boundaries of multiple colonies, Virginia could not negotiate by itself for frontier peace. In 1684, Virginia Governor Effingham joined with the colonial governor of New York to sign a treaty that brought a temporary easing of tension on the edge of settlement. New York governors would later call for Virginia support of the Iroquois who were assisting in attacks on the French and their allied tribes in Canada, but the Virginians were reluctant to fight just to protect the fur trade capabilities of the New Yorkers.9

Bacon's Rebellion demonstrated, among other things, that the success/failure of English settlement in North America would require cooperation among the colonies - and that success/failure of Native American resistance would require cooperation among the tribes.

the rebels led by Nathaniel Bacon burned Jamestown in 1676

Source: Mary Tucker Magill, History of Virginia for the Use of Schools (1873, p.102)

behind the chair of the Speaker of the House of Delegates in the State Capitol is a memorial to Nathaniel Bacon

Nathaniel Bacon burned Jamestown on September 19, 1676

Source: Harper's Encyclopaedia of United States History: from 458 A.D. to 1905, The Burning of Jamestown (by Howard Pyle, 1905, and as published on Wikipedia)