The Military in Colonial Virginia - an International Frontier

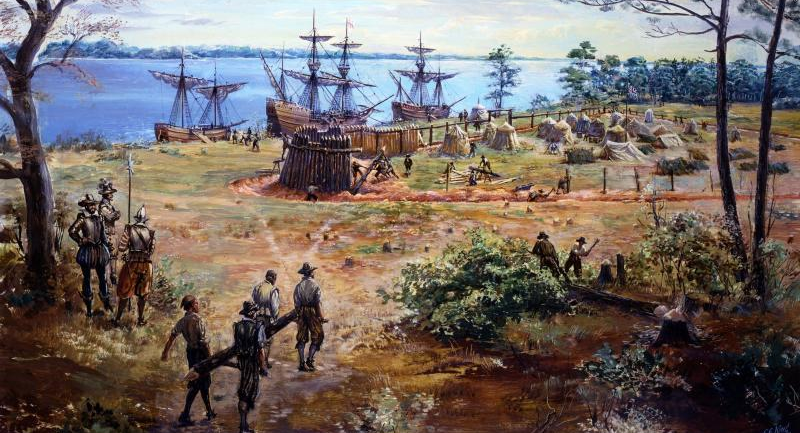

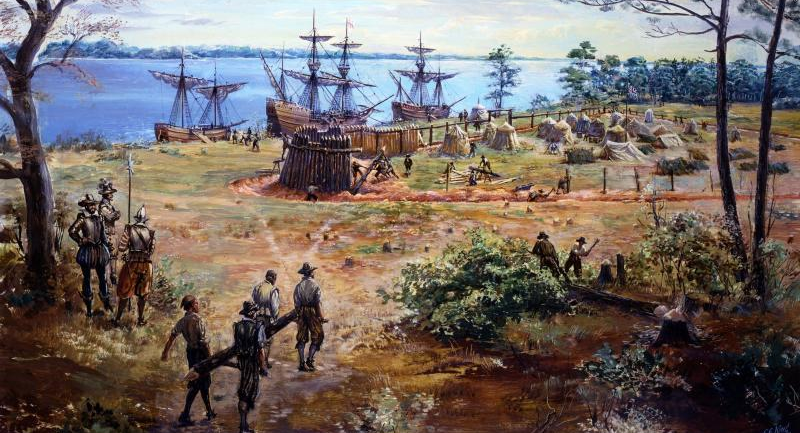

the Jamestown fort provided protection against Native American assaults, but its design ensured most cannon faced the river to protect against attack by European ships

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings, Colonists Landing at Jamestowne

Jamestown was an international seaport from the beginning, but Virginia was poorly protected by English forces based in Europe across the Atlantic Ocean. For the first 80 years of English settlement, the colony had to rely primarily upon its own resources to defend against attacks by Native Americans, assault by ships from other European countries, or raids by pirates. Blackbeard, the most famous pirate, was finally killed through the initiative of Virginia governor Alexander Spotswood in 1718.

The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 blunted the potential of Spain to invade England, but Spain remained dominant in the New World for another century. England's rise to international power began after William and Mary took the throne in 1688. However, in the early 1700's - a century after Jamestown was founded - the mother country still struggled to provide guardships to protect the tobacco fleet in the Chesapeake Bay from pirates.

Virginia colonists anticipated attack by the Spanish from the very beginning, and throughout the 1600's. In 1607 Edward-Maria Wingfield followed the directions issued by the Virginia Company and located the new colony upstream on the James River, rather than at the more-convenient location of Point Comfort.

the first English settlers at Jamestown came prepared to fight the Spanish

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings, Colonists Landing at Jamestowne

Spain feared colonies of other nations north of Florida would become bases for pirates to capture Spanish ships sailing from the Caribbean to Seville. In 1609 and 1611, King Phillip III of Spain dispatched expeditions to Virginia to spy on the Jamestown colony. His ambassador in London gathered intelligence as well.

The 1609 Spanish expedition was chased away from the Virginia coastline by English ships. The spies in the 1611 expedition were captured when they arrived at Fort Algernon at Point Comfort, rather than welcomed as fellow ocean-crossing European travelers. One spy, Don Diego De Molina, managed to smuggle a letter home that made clear Spain should destroy the English colony before it grew further. He encouraged Phillip III to:1

- ...stop the progress of a hydra in its infancy, because it is clear that its intention is to grow and encompass the destruction of all the West, as well by sea as by land and that great results will follow I do not doubt, because the advantages of this place make it very suitable for a gathering-place of all the pirates of Europe...

Spain never attacked the Virginia colony. The Spanish missed their best opportunity to conquer England itself when the Armada was defeated in 1588, but remained a threat to the British colonies in North America. In 1686 Spanish troops based at St. Augustine did destroy Stuart's Town near modern Beaufort, South Carolina. Stuart's Town was an attempt in 1684 by Scottish Presbyterians to start a colony separate from the new Carolina settlement at Charles Town. Stuart's Town survived only two years. After the Spanish attacked and burned it, the colony was abandoned.

By the time the English concluded their major Civil War in 1660, rejecting Puritan rule and restoring Charles II to the throne, the Spanish had lost control over the Netherlands and Portugal. Spain failed to use its wealth from Mexico and Peru to create a strong domestic economy, and their potential to expand further north beyond their base at St. Augustine disappeared by the end of the 17th Century.

It was the French, more than the Spanish, who challenged English authority most often in North America. The French under Louis XIV finally established a solid financial foundation for funding national expansion and paying for the strongest army in Europe. Had the French king chosen to send more than just a token number of troops to Canada and treated his colonies there as more than collection warehouses for the fur trade, France might have ended up the dominant military power in North America.

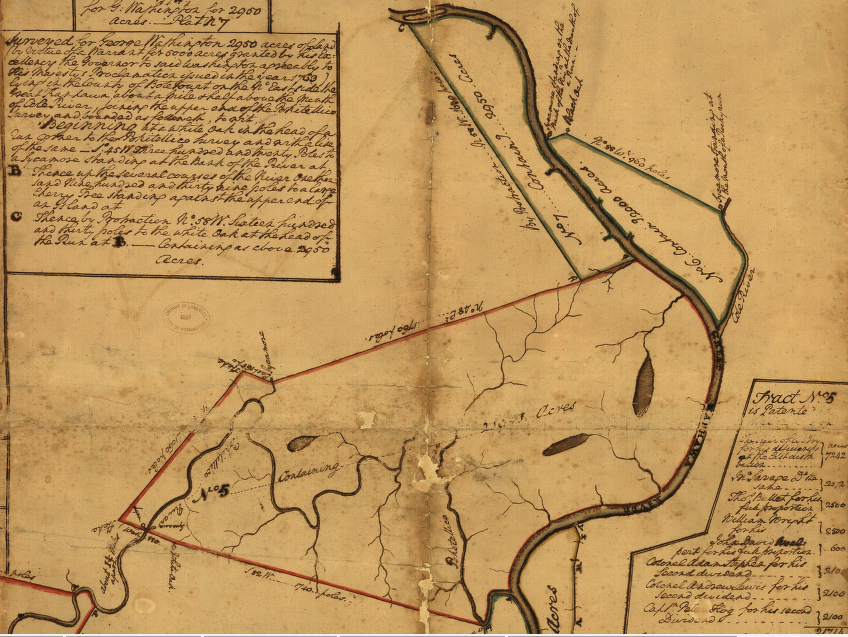

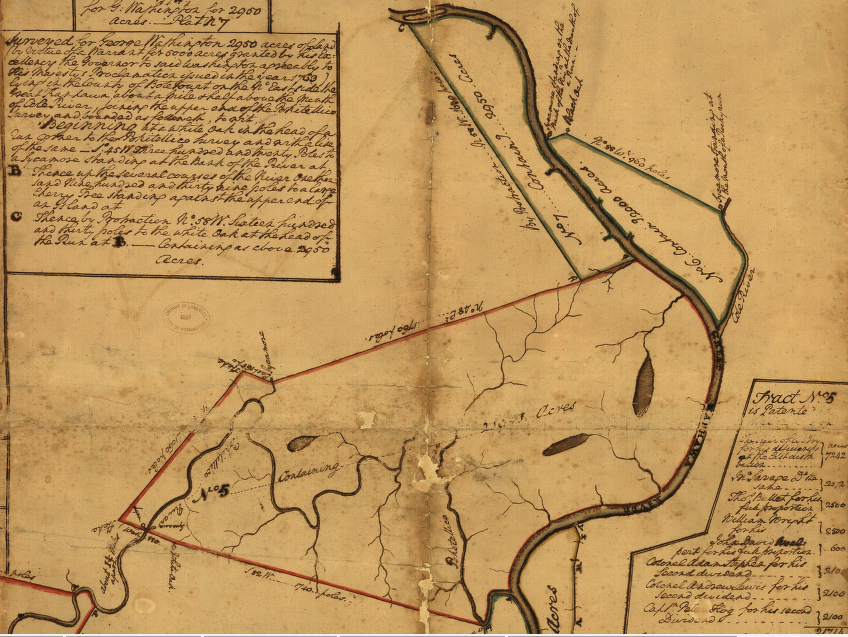

France exported its feudal society to Canada, including the seigneur system of land distribution where land was surveyed into long, rectangular strips with frontage on a river, bottomland for farming, and uplands for wood supply. In Virginia, land-hungry colonial leaders incorporated as much good farmland as possible in their metes-and-bounds surveys.

pattern of land ownership on St. Lawrence River downstream of Montreal still reflects the system of land distribution in New France

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

George Washington carefully surveyed his land claims on the Kanawha River to include the maximum amount of productive bottomland, leaving the less-valuable hills for land claimants who came later

Source: Library of Congress, Eight survey tracts along the Kanawha River, W.Va. showing land granted to George Washington and others

One weakness of French government in Canada was that power was divided between a governor, a Catholic bishop, and an "intendant" responsible for finances and legal activities. France tried to settle Canada by issuing land grants (seignories) comparable to the proprietary colonies of the English, such as Maryland, the Carolinas, and Pennsylvania. The king's friends tried to make their land grants profitable by requiring settlers to pay high fees for renting the land, rather than offering low land costs to maximize settlement and then trying to profit somehow from a growing colonial economy.

The French did try to spur settlement by offering some soldiers stationed in Canada a land grant, rather than shipping them home after the tour of duty had ended. Joseph Coulon de Villiers, sieur de Jumonville, was killed by George Washington's forces in 1754, triggering the French and Indian War - and he was in North America because his grandfather had been a soldier awarded a land grant.2

The French colonies also pre-dated the arrival of the English at Jamestown. In 1605, Samuel de Champlain started a colony at Port Royal in Acadia. It was a failure in part because Virginians under Samuel Argall destroyed this rival settlement in 1613. Quebec became the most successful French colonial capital, after Champlain founded that city in 1608.

In the end, the French were able to explore the North American continent and exploit the fur trade by doing business with Native American allies. French traders spread throughout the upper Mississippi River watershed, land that George Rogers Clark captured in the American Revolution and Virginia organized into Illinois County. The French never "adventured" enough money or people to dominate the continent, and lost Canada in the French and Indian War. Napoleon sold the last major French land claim in 1803 when another land-hungry Virginian, Thomas Jefferson, purchased the Louisiana Territory for the United States.

in colonial North America, French land claims (yellow) conflicted with English (light green) and Spanish (pink) claims

Source: Maine State Archives, "Amerique Septentrional," L'Amerique Septentrionale (1708)

The colonies themselves were too weak to supply troops for British imperialism, outside the colony, until the War of Jenkins Ear in 1739-42. Virginia recruits were involved in five separate conflicts between the English and their European rivals in North America and the Caribbean during the colonial era:

- King William's War, 1689-1697

- Queen Anne's War, 1702-1713

- War of Jenkins Ear, 1739-42

- King George's War, 1744-1748

- French and Indian War, 1753-63 (or the "Seven Years War," counting just the European phase)

The first three times, the colonial warfare was a reflection of the rivalries for power in Europe; most fighting was on the new England/Canada frontier. The last time, it was Virginia's expansion into French-claimed lands along the Ohio River that triggered the fighting. That war then spread to Europe and even India, becoming the first "world war."

Warfare in colonial Virginia was substantially different from warfare in Europe. It was far harder to raise an army and to supply it on the edge of European civilization. There were surpluses of tobacco and timber in the English colonies, but not of men, clothing, weapons or food. Capture of fortified houses west of the Blue Ridge required little expertise or equipment for siege warfare, but also provided far less plunder than the capture of cities in the dukedoms of Europe.

The training of the colonial militia was occasional and usually informal. Militia musters were primarily social events, unless there was an immediate threat of some sort. Though farmers on the western frontiers maintained weapons for personal use, the assembly of county militias often demonstrated that the community was unable to defends itself against anything other than a quick raid by a band of Native Americans. (The Second Amendment in the US Constitution defined the right to bear arms by a well-regulated militia... which was not well-regulated during most of the colonial era.)

No Virginia towns were fortified against attack by naval bombardment until after the American Revolution. The primary defense during the colonial era was the British Navy, which also protected the tobacco ships which sailed annually to England.

European colonies on Caribbean islands were prepared to repel attacks by foreign navies, but Virginia's General Assembly was unwilling to finance substantial forts or a standing army. The main security against foreign attack was the strength of the British navy, financed by residents in Great Britain rather than by direct taxes on the colonies. The size of the military was controlled by Parliament, which was reluctant to approve taxes except in time of war.

There was little need of a European-style army in Tidewater Virginia. The Spanish in Florida were few and far away, as were the French in Canada. The Virginians were not prepared to fight a sustained battle against any army. The Native Americans did not line up in ranks and fire in unison - so why should the Virginians organize according the European model and fight according to European tactics, when the main threat on the frontier were American Indians?

In January 1776, at the start of the Revolutionary War, Rev. Peter Muhlenberg was representing Dunmore County at the Fourth Virginia Convention in Williamsburg. The convention gave him the responsibility to raise soldiers for the 8th Virginia Regiment and to serve as its commander.

He returned to his county to recruit soldiers, and arranged to give a farewell sermon at the Beckford Parish church in Woodstock. Though ordained as an Anglican minister, he was a Lutheran in his personal beliefs.

According to a story told by his great-nephew in 1849, Rev. Muhlenberg finished with a flourish. He removed his ministerial robe and revealed he was dressed underneath in military uniform, with a sash and sword, and said (possibly in German rather than English):3

- ...there was a time for all things, a time to preach and a time to pray, but those times had passed away . . . that there was a time to fight, and that time had now come!

A different version of the story, written in 1778 by a a Revolutionary War surgeon and thus less prone to alteration over time, says Rev. Peter Muhlenberg was wearing his uniform openly when he entered the pulpit and started his sermon. Both versions claim he recruited 300 soldiers for his regiment, with drums beating at the church door, before leading his men to Suffolk in March.

Most likely, the local commanders (captains) of the 10 companies did the majority of the recruiting seeking to raise 68 men to serve in each company. A stirring speech from the Colonel of the regiment, with the eloquence of an experienced minister, certainly would have helped. About 1/3 of the recruits who joined the 8th Virginia "German" Regiment were German-speaking Virginians.

The story of peeling back clerical robes to reveal a military uniform may have been manufactured later. The image of Rev. Muhlenburg dressed in the blue uniform of a general may also be incorrect. In 1776, the most common clothing worn by the recently-recruited Virginia troops was a hunting shirt.

The Rev. Muhlenberg was popularized in the Shenandoah Valley during World War I and World War II in an effort to show that German-Americans were loyal patriots during the American Revolution. His log church, thought to have been located at the intersection of Main and Court streets in Woodstock, has not survived. However, the modern Muhlenberg Lutheran Church in Harrisonburg commemorates the event with a stained glass window showing the minister speaking at the pulpit with a sword hanging by his side.4

Links

References

1. "Letter of Don Diego De Molina, 1613," in Narratives of Early Virginia, 1606-1625, http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/jamestown-browse?id=J1045 (last checked October 13, 2013)

2. Christina Dickerson, "Diplomats, Soldiers, And Slaveholders: The Coulon De Villiers Family In New France, 1700-1763," PhD dissertation, Vanderbilt University, 2011, p.xiii, http://etd.library.vanderbilt.edu/available/etd-03222011-085548/unrestricted/DickersonDissertation.pdf; "Stuart's Town," South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/stuart%C2%92s-town (last checked August 8, 2025)

3. Michael Cecere, "The Fighting Parson’s Farewell Sermon," Journal of the American Revolution, April 15, 2020, https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/04/the-fighting-parsons-farewell-sermon/; Henry A. Muhlenberg, The Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg of the Revolutionary Army, Carey and Hart, 1849, pp.53-54, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000315636 (last checked April 16, 2020)

4. Michael Cecere, "The Fighting Parson’s Farewell Sermon," Journal of the American Revolution, April 15, 2020, https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/04/the-fighting-parsons-farewell-sermon/; Henry A. Muhlenberg, The Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg of the Revolutionary Army, Carey and Hart, 1849, pp.53-54, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000315636; "'A time to pray and a time to fight'," Cardinal News, December 12, 2023, https://cardinalnews.org/2023/12/12/a-time-to-pray-and-a-time-to-fight/ (last checked December 13, 2023)

The Military in Virginia

Virginia Places