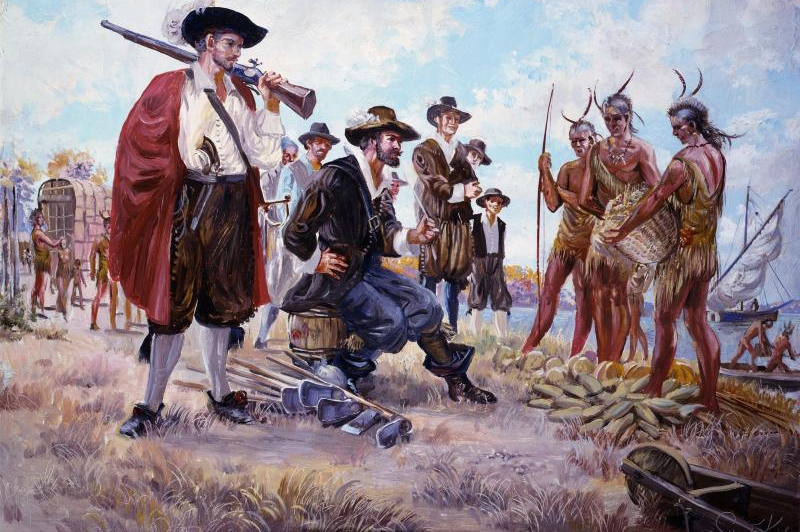

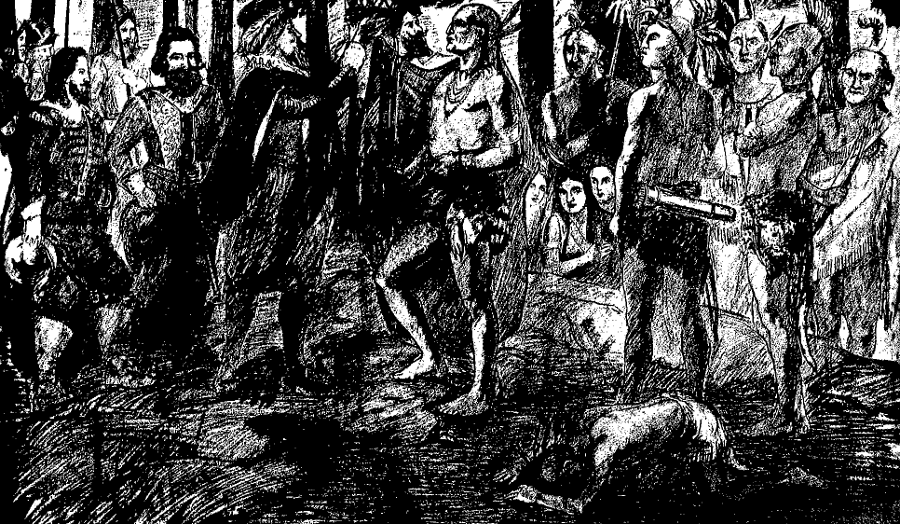

Native Americans and English traders both came armed, and did not assume every deal would be negotiated peacefully

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings, John Smith Trading With the Indians

Native Americans and English traders both came armed, and did not assume every deal would be negotiated peacefully

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings, John Smith Trading With the Indians

The English sailing to Jamestown understood that the occupants of the New World might be hostile. The detailed story of Father Juan Baptista de Segura's short stay in 1570-71 may not have been known to the English, but those on the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery knew that the Roanoke Colony had disappeared 20 years earlier.

Relations between the English colonists and the Native Americans in Virginia were hostile from the very first day. When the English first came ashore at Cape Henry on April 26, 1607, two of them were wounded by arrows from Native Americans.

The English response, after they explored inland and rowed across Hampton Roads to discover Point Comfort, was to build a cross at Cape Henry. They could have built a fort there, but the instructions were to move inland.

Shortly after arriving at Jamestown Island three weeks later, Edward Maria Wingfield (first President of the Council) ordered that just a brush barrier be constructed to protect the colonists on unoccupied Jamestown Island. A brief flurry of arrows then convinced the Council that a stronger fort had to be constructed immediately.

The English were worried about more than just the Native Americans under Powhatan's control. Our only contemporary image of that Jamestown fort comes from the Spanish archives, which retained a copy of the 1608 drawing provided by a spy to Spanish ambassador Pedro de Zúñiga. John Smith or his cartographer may have produced the map, which was sent to London and perhaps intercepted there by the Spanish.

sketch of triangular fort at Jamestown

Source: The "Zuniga Chart" of Virginia, 1608

The English were wise to worry about their European rivals. There really was a threat of invasion of Virginia by international enemies, in addition to the domestic threat from Native Americans that were being displaced, in 1607.

re-creation in 2006 of James Fort palisade, along the James River

(the modern John Smith statue faces what would have been the main entrance to the fort)

Under international law - as the Europeans defined it - the English were entitled to claim Virginia by right of discovery. The European nations knew the lands in the New World were not "empty." However, the Europeans asserted rights to lands that were not occupied by any *Christian* prince.

The colonists made their claim to Virginia clear with a religious symbol, by erecting a cross at Cape Henry when they arrived. The English claimed exclusive territorial title by right of discovery, and the cross alerted any other Europeans that the colonists would defend that claim.

Europeans also claimed lands by right of conquest. After the English defeated an enemy, they felt entitled to claim exclusive rights to the lands of the enemy.

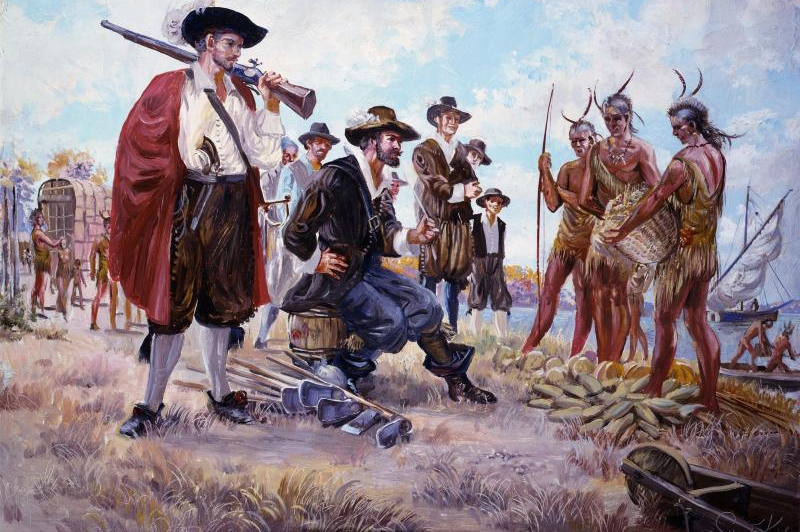

Powhatan also asserted a claim to the territory of defeated enemies and rivals. In the mid-1590's, 15 years before the English colonists arrived, he expanded the boundaries of his paramount chiefdom, the territory the Algonquian-speaking Native Americans called Tsenacommacah.

He seized control of the town of Kecoughtan, at the tip of the Peninsula and site of the modern city of Hampton. The group living there may have been allied with other tribes in southeast Virginia/northeast North Carolina. Powhatan's warriors killed the weroance (chief), along with many members of the tribe occupying that land. Powhatan repopulated the site with his subjects and installed his son Pochins as the new weroance.

Powhatan also conquered the Chesapeake tribe in what today is Norfolk/Virginia Beach, and seized control over their territory. According to William Strachey, Powhatan ordered the slaughter of the tribe to block a prophecy of his priests that "from the Chesapeake Bay a nation should arise which should dissolve and give end to his empire."1

location of different tribes in Virginia in 1607

derived from Virginia Department of Historic Resources - First People: The Early Indians of Virginia, portrayed on Frye-Jefferson map (1751)

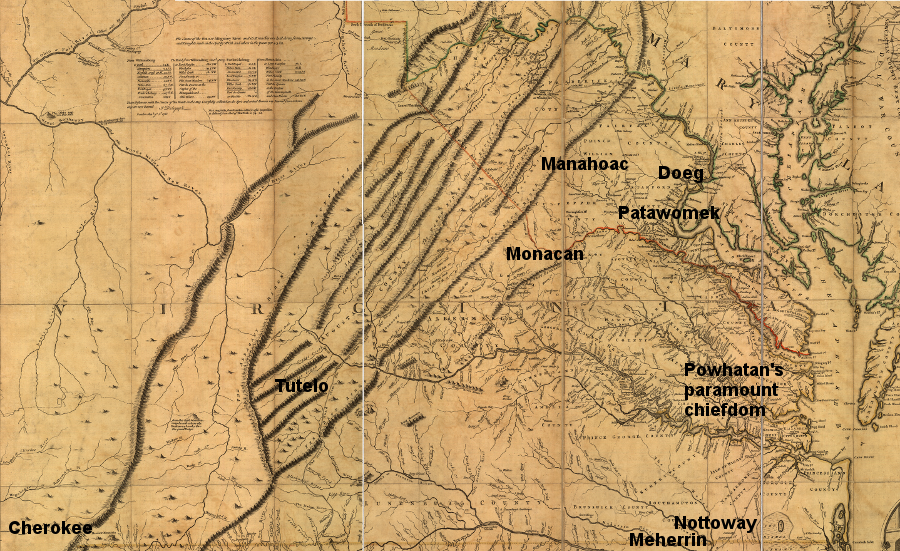

Powhatan was the leader of the Virginia tribes who occupied the lands where the English arrived. There were other non-Algonquian tribes in 1600 west of the Fall Line, and Algonquian-speaking tribes north of the Rappahannock River that did not consider Powhatan to be their paramount chief, but the English happened to sail into Powhatan's turf. His authority over 30+ tribes was enhanced by his skill asserting his dominance through dress, architecture, and behavior as well as through force.

John Smith was clearly impressed when he first met Powhatan ("their Emperour") in his capital in January, 1608:2

Powhatan established his leadership role with drama as well as force

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith

Powhatan did not try to expel the English from his territory, Tsenacommacah. He knew how much effort was required to carve a canoe with shell and fire, and to create wooden palisades that protected towns. The strange-talking, light-skinned, bad-smelling "tassantassas" with the sharp iron tools and guns had value.

Powhatan's primary war aim was to acquire technology and status goods (shiny glass beads and copper) from the English, without losing control of his territory to the European arrivals.

Powhatan's people had little access to the stone needed for their knives, points, axes, and other tools. Tsenocomoco was limited to the Coastal Plain where thick layers of loosely-consolidated sediment covered the bedrock. The Algonquian-speaking tribes under his control had to trade with rival Siouan-speaking Manahoac and Monacan living above the Fall Line, or expose gathering parties to attack while searching for good stone among the cobbles in the rivers at the Fall Line.

If Powhatan could obtain a new source of tool-making material from the English, and get a material (iron) better than stone, then he would be in a greater position of strength. With new weapons, he might even gain the power to expand Tsenocomoco westward into the Piedmont.

Powhatan's strategy, the way he implemented his war aims to obtain prestige goods and iron tools from the English, was to control food supplies. Starving colonists would be dependent upon him. His tactics, the way he implemented his strategy, was to mix diplomacy with fighting.

He was not the first or the last Native American leader who sought to mix accommodation in order to obtain trade with resistance in order to protect territory. When the first colonists arrived in Maryland, they met with the local weroance of the Piscataway tribe and indicated he wanted to settle in the area. The Native American leader told Governor Calvert:3

The English war aims were equally simple: extract wealth from Virginia, preferably in the form of gold, silver, and jewels that would be valued in Europe. They too hoped to avoid fighting.

The English would have been happy to fight if it would lead to immediate looting of a hoard of gold/silver, as the Spanish experienced in Mexico and Peru. In Virginia, John Smith's involuntary visit to Werowocomoco in 1608 revealed that Powhatan had no stockpiles to steal other than corn. For the colonists, military activity was a distraction from the planned accumulation of wealth.

The first settlers at Jamestown expected to defend their new territory from the Spanish, Dutch, and French. For those colonists who were planning to be in Virginia only briefly, fighting to acquire long-term title or ownership of the land from the Indians was a low priority.

Like the leaders on the Council, the top employees of the Virginia Company planned to get rich. They also planned to return to Europe; the first English immigrants to Virginia were not refugees who planned to cross the Atlantic Ocean once and never return "home" to England. The Virginia colonists were not religious zealots seeking freedom to live and worship differently in a new land, or political dissidents seeking to create a new society.

For every supply ship that arrived at Jamestown, there was a ship sailing back to England that offered a chance to go back. Though the Virginia Company planned to establish a permanent colony, the personal objectives of the early colonial leaders were different. They planned to stay in Virginia only temporarily. All of the early leaders at Jamestown who survived the first years, including John Smith, did return back to England.

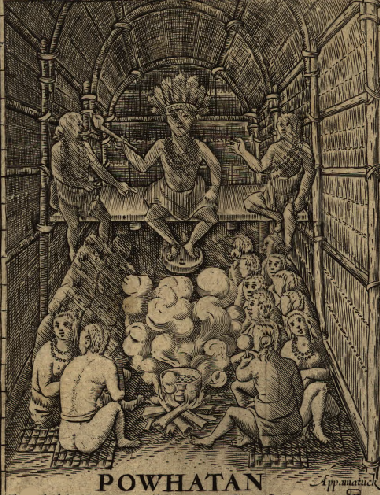

The English quickly realized that the Virginia colony was not going to be a source of mineral wealth comparable to the areas occupied by the Spanish. Virginia would not offer a get-rich-quick opportunity, but did offer avenues to wealth and influence. The Virginia Company directed Christopher Newport to crown Powhatan. Defining him as a subordinate leader to the King of England may have provided more benefits within the web of court relationships in London than in Virginia.

Captain Christopher Newport had to press hard to get Powhatan to kneel slightly, when he placed a crown on his head at Werowocomoco

Source: Bureau of Indian Affairs, Famous Indians

In 1610, the English decided there was nothing in Virginia worth certain death from starvation. Those who had survived the Starving Time in Jamestown, or wintered on Bermuda after the shipwreck of the Sea Venture, recognized that they had too little food to survive until a harvest.

All of the colonists climbed on board their ships and sailed downstream towards England. At Mulberry Island near the mouth of the James River, however, they met Lord de la Warre with a resupply. The English returned to Jamestown, glad that they had not torched their fort and houses as they had abandoned the town.

Bottom Line: Powhatan's alternating pattern of hot and cold war would have been a spectacular success, had the retreating English not met Lord de la Warre's resupply. Powhatan would have retained control of the Peninsula and the rest of his confederacy, along with the prestige copper and functional iron tools he had acquired from the English.

Lord De la Warre arrived in the nick of time on ships with cannons, prepared to fight any Spanish ships that might threaten Jamestown

Source: National Park Service, Sidney King collection of paintings created for the 350th Anniversary of Jamestown

Lord de la Warre personally assumed control of the colony in 1610 when he arrived, supplanting Sir Thomas Gates as acting governor and permanently ending the president-council structure. Powhatan was forced to deal with a more-aggressive occupier.

The English intensified their military efforts. By burning Indian cornfields and displacing Native American residents from their traditional townsites, the Virginia Company asserted permanent control over much more territory. Lord de la Warre's use of scorched-earth tactics was comparable to those used by the English in Ireland, as the English seized control of that island from the Celtic residents.

The new governor was effective at implementing the commercial aims of the Virginia Company. The investors wanted to establish a permanent community in Virginia. That would provide company employees a stable base from which to seek wealth from undiscovered resources, and perhaps to find a Northern Passage facilitating trade with China.

The successful basis of the colony was a surprise to the investors. Virginia survived due to agriculture rather than mining or trade, or production of energy-intensive products such as glass.

Growing corn and wheat was originally just an incidental aspect to colonial settlement. John Smith and other early leaders struggled to get the Jamestown residents to farm or even to fish. Colonists finally realized that growing their own food was a necessity because supplies from England and the local Native Americans were unreliable, and the Virginia Company relaxed its work requirements so colonists could grow food for themselves rather than just for the company storehouse.

In 1613 John Rolfe planted a crop of tobacco with seeds imported from the Caribbean islands. After that crop was sold in Europe for a high price, competing successfully against Spanish-imported tobacco, the Virginia Company changed the goals for its business venture in Virginia.

The company's new purpose for investing in the colony was still to gain wealth, but through agricultural production. "Virginia leaf" became more popular in Europe than the harsher-tasting "Spanish leaf." In those days, there were no filters or flavorings like menthol to smooth the smoke, so the quality of the tobacco was critical to the taste.

harvesting tobacco leaves on the Peninsula in the 1600's before drying and "prizing" them into hogsheads (barrels) for shipping to Europe

Source: National Park Service - Sidney King collection of paintings created for the 350th Anniversary of Jamestown

The Virginia soils on the Peninsula were naturally fertile, but would yield good tobacco crops for only 2-3 years with no fertilizer. After the nitrogen and other nutrients in the soil was exhausted, the English needed to occupy fresh territory. That pushed the colonists to expand their boundaries into territory that had been controlled by the tribes under Powhatan's authority. The English seized the existing fields and even towns of the Indians, because the trees had already been cleared and they were the most-convenient lands for growing a new crop of tobacco.

Tobacco changed the business priorities of the Virginia Company in England, and tobacco changed the operations of the company's representatives in Virginia. Tobacco made control over territory, and private ownership of land, far more important.

In contrast, the French along the St. Lawrence River relied upon fur trading for profits and displaced few Native Americans in order to grow food to support the small population living in Quebec and other trading posts. The Spanish in Florida had small garrisons to prevent France and other nations from establishing privateering bases on the North American coast. The Spanish garrisons could rely upon food grown locally by Native Americans who were willing to trade, in part due to conversion and acculturation by Catholic priests.

The English often tried to acculturate the Powhatans and convert them to the English religion and lifestyle. However, the English efforts at Christianizing the "heathen" were much less intense than the Spanish efforts further south in Florida.

The Catholic Church was an independent power that had its own desires to increase its influence by winning converts in the New World. The Anglican church in England was much more subordinate to the monarch, after King Henry VIII split the English church away from the control of the Pope in Rome and seized the monasteries. That event, long before Jamestown, may have been a key reason why the English colonists in Virginia treated the Native Americans differently from the Spanish.

The English tactics were similar to Powhatan's - spurts of overt hostility, mixed in with attempts to replace open warfare with a warm peace or at least a cold war. Neither side wanted to invest the resources in constant, intense fighting. Powhatan had more people, but the English had better technology.

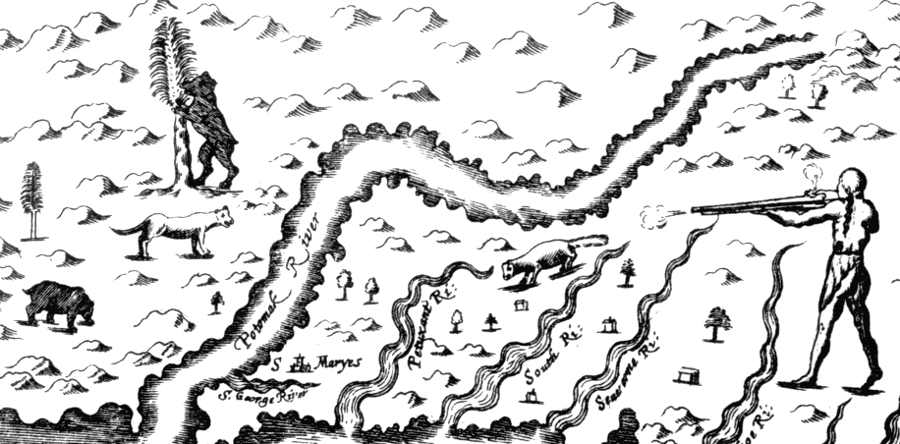

Native Americans gained access to guns and gunpowder soon after the English arrived at Jamestown

Source: "The Maps and Map-Makers of Maryland," A Land-skip of the Province of Maryland (by George Alsop, 1666)

The technology-limited Native Americans had to trade with the English for guns and gunpowder, since they were unable to manufacture their own. The English needed food and purchased deerskins and other goods for export. had water-based mobility, but they were not completely safe in their sailing ships. They had to keep a guard against a canoe-based attack, when the sailing ships were near the Virginia shoreline. Think the English believed their way of life was as superior as their technology, and that the Algonquians would be willing (or could be coerced) to abandon their traditional culture?

John Rolfe's marriage to Pocahontas was one temporarily-successful attempt to establish peaceful coexistence between the English and the Native Americans. Powhatan and the English both took a calculated risk when they approved that marriage, and it led to eight years of peace.

the marriage of Pocahontas to John Rolfe led to an eight-year pause in warfare between the Native Americans and the colonists

Source: Wikipedia, Pocahontas

The Virginia colony could have created a blending of two cultures, with the Algonquians adopting English technology and the colonists adopting farming, hunting, and housing patterns from the Native Americans. Both cultures could have modified their perspective on land ownership and racial identify, shifting from "us vs. them" to a society where intermarriage and mixed offspring were common.

By 1622, the colonists were encouraging the Algonquians to visit regularly in the English houses and to adopt English patterns of life. However, Opechancanough's uprising sought to eliminate the "other" culture from Virginia, and brought an end to the concept of integrating the Native Americans into English culture. 400 years later, history books are just beginning to consider the Algonquian perspective on colonization.

The marriage of Pocahontas and John Rolfe can be viewed as a prelude to the final decision by the English to suppress the Algonquian culture in Virginia. She navigated the rituals of English society, in the colony and finally in London. After 1613, it was a one-way street for Pocahontas to "become English," at least in her superficial characteristics of dress and language, while her English husband adopted few if any Algonquian habits.

For centuries, English/American artists have emphasized how Pocahontas adopted English manners and dress. By the time she was captured in 1613, she may have already been married to an Algonquian named Kocoum and may have had tattoos on her face (a symbol of high status)... but no English portraits show her with tattoos.

One possibility: Pocahontas may have been happy choosing John Rolfe as her new husband, rather than returning to her tribe. In her old culture, she was just one of many children fathered by the paramount chief. Powhatan used her as an ambassador to the Patawomeck tribe - and when they sold her to Captain Samuel Argall for a copper kettle, Powhatan did not complete negotiations to ensure her return.

In English society, however, Pocahontas was quickly provided status as someone very special, a "princess" with a father who was the equivalent of a king. Perhaps she chose, willingly, to switch rather than to fight.

On the other hand, it's an old saying that people fight for "their way of life." Maybe Pocahontas voluntarily adopted a new culture after her marriage, blending her old and new culture together so she got the best of both worlds - or she may have simply masqueraded as English, but was still a fully-Algonquian woman dressed in different clothes. She died three years after marrying John Rolfe, so there is inadequate evidence to assess her motivations.

Pocahontas is on official seal of Henrico County

It is clear that few other Algonquians chose to trade lifestyles. The Europeans had little success converting the adult Algonquians to adopt English religion, clothing, or housing - though the Algonquians were quite sophisticated in their capacity to acquire and use English technology, while still living in Algonquian towns, growing crops the Algonquian way, and dressing in the Algonquian style.

The hard life for an indentured servant in the colony attracted immigrants from England primarily because Virginia offered a chance to acquire land from Powhatan and his subordinate tribes. To the Algonquians, English title to land they already controlled was no incentive. The English had a little success with the young Algonquian children that Powhatan and his successors permitted to live in English households, but that ended in 1622.

how the interior of an English colonist's house may have appeared in 1622

Source: National Park Service, Sidney King collection of paintings created for the 350th Anniversary of Jamestown

By March 22, 1622, Powhatan had died and been replaced by Opechancanough. A thumbnail description of the situation by Phillip Levy summarizes what he faced:4

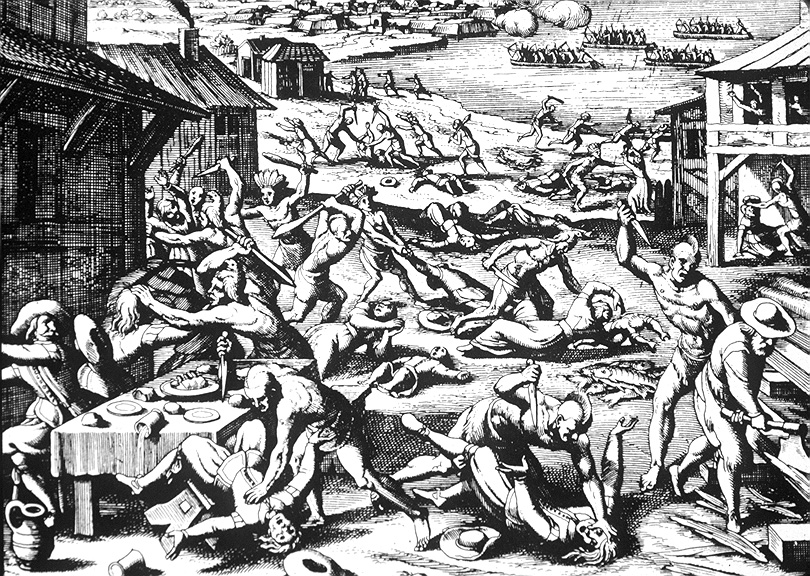

The English did not view Opechancanough as overtly hostile, and the Native Americans retained easy access to the English houses. As a result, Opechancanough was very successful in surprising his enemies on March 22. The Algonquians were visiting and working as usual, indoors and outdoors, with the English that day.

Starting at noon, however, the peaceful conversation stopped. The Algonquians started attacking English men, women, and children with knives, hatchets, and farm implements. About 350 English died in the uprising, which the English labeled a "massacre."

Theodore De Bry engraving of March 22, 1622

Source: Indians of North America - Theodore De Bry Woodcuts

That event marks the end of Powhatan's strategy of accommodation in order to achieve rare goods and technology, while constraining the English to a small portion of Tsenacommacah.

The 1622 uprising also marks the end of English accommodation. For the English, peaceful coexistence was replaced by a policy of excluding the Algonquians from English settlements, literally building a wall across the Peninsula. Native Americans were required to wear official badges when trading with the English, in territory once occupied by the Chickahominy, Paspahegh, Kiskiack, Kecoughtan, and other tribes.