black bears are omnivores, and can live in a wide variety of habitats

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, The Virginia Appalachian Carnivore Study: Black Bears & White-tailed Deer in the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia

black bears are omnivores, and can live in a wide variety of habitats

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, The Virginia Appalachian Carnivore Study: Black Bears & White-tailed Deer in the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia

Virginia has black bears (Ursus americanus) which range in color from light brown to dark black. There are no grizzly or polar bears in Virginia.

Black bears gorge during the Fall on acorns and whatever else they can find, then stay in a den (usually a hollow tree) during the winter. In years when oak trees produce a lot of acorns, bears travel less for food and hunters harvest fewer bears.

Bears emerge occasionally on warm days in the winter. In the Spring, they will start ranging through their territory for food and mating. In western Virginia, bears that emerge from hibernation are more likely to feed on fawns (as do bobcats and coyotes). Most are scavenged, but some fawns are hunted by bears. The 2025 Virginia Appalachian Deer Study did not document hunting of adult deer, but their carcasses were scavenged for food.

The study documented that 2/3 of a bear's annual diet was fruit and seeds. Including acorns, nuts, fungus, and leafy matter, bears were 90% vegetarians. However, in the spring deer composed over 12% of their diet.

Females mate every other year, and force their cubs to "move on" after the second winter.

mothers of black bears force their cubs to find their own territories after the second winter of care

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bear cub at Shenandoah National Park

Those young bears must find their own territory, and will appear in suburban areas. When the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources is called because bears are eating at birdfeeders, dog food bowls, and garbage cans in back yards, or found wandering on the Washington and Old Dominion (W&OD) Trail in Fairfax County, the state agency focuses on managing the people rather than the bears. If left alone, the bears will wander away and cause no harm. If people try to chase a bear away with sticks, shouting, and arm-waving, they may irritate the bear and get slapped.

When bears decide that a corn field offers a reliable food source, farmers can lose up to 20% of their crop. Special permits for animal damage control allow farmers to hunt bears prior to the official opening of the season, and in some cases even to kill bears at night. In 2013, the natural acorn crop was poor around Shenandoah County, and bears caused an unusual amount of damage in farm fields while looking for substitute food prior to the long winter denning. The bear population is also increasing, creating more bear-human conflicts.1

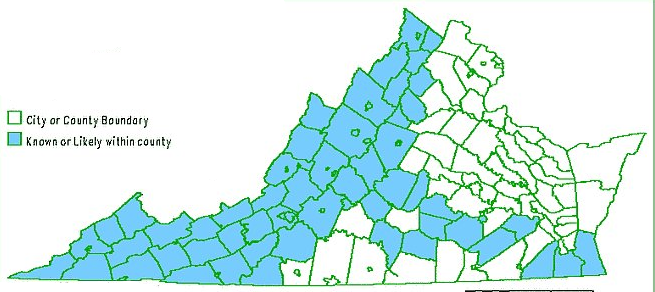

in 2003, black bears were not residents of Northern Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Black Bear (Ursus americanus)

Unprovoked attacks by bears are rare. When hikers in parks and forests encounter bears, usually the bear simply moves away. Occasionally, however, a person will walk between a mother bear and her cubs, or a hiker's dog might challenge a bear. One such incident in 2014 resulted in a hiker in the George Washington National Forest getting clawed and bit, requiring a trip to the hospital in Winchester.2

Moving "problem bears" is expensive, and requires identifying an isolated location for a problem bear's new home. In 2025, after the Maryland Department of Natural Resources relocated a bear that appeared in a Prince George's County backyard, it wandered into the Town of Herndon. It climbed a tree on Elden Street, becoming a popular celebrity town officials named "Elden."

After deciding the young bear was unlikely to wander naturally out of suburbia, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources tranquilized Elden and relocated him a second time to an undisclosed location in the Shenandoah Valley.

when he arrived in Herndon, Elden wore a GPS collar installed when relocated by Maryland wildlife officials

Source: Herndon Police, Instagram post

The National Park Service transports an average of 5-10 bears annually that were too intrusive into campgrounds at Great Smoky Mountain National Park in Tennessee/North Carolina. The bears are released in Cherokee National Forest with ear tags, but nearly 75% are never seen afterwards. The National Park Service wildlife biologist said, at the start of a project to track the bears with Global Positioning System (GPS) collars:3

black bears climb trees to find shelter, or escape hunters with dogs

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, American Black Bear

Bears were in Virginia before people. They migrated from Siberia about 7-8 million years ago.

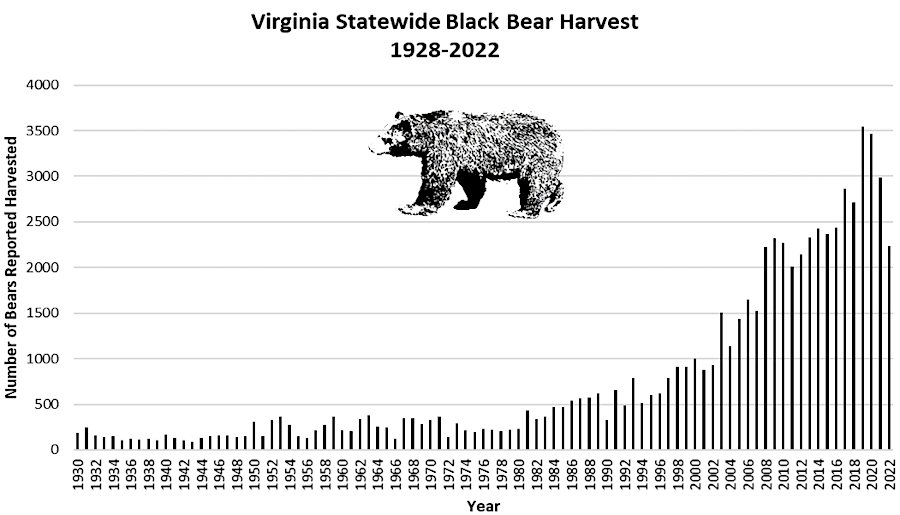

The bear population declined in Virginia as farming replaced forested habitat with cropland and hayfields in the 1800's. Overhunting reduced the population to 1,000-1,500 bears before the state implemented hunting seasons and wildlife management programs in the early 1900's. The largest remaining population of black bears east of the Blue Ridge before hunting controls were implemented was in the Dismal Swamp.4

Abandonment of marginal agricultural lands in the 1900's, especially in mountainous areas, led to reforestation and expanded habitat suitable for bears.

The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (now Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources) adopted Black Bear Management Plans in 2001 and 2012. They identified areas where bear populations should be managed to increase, decrease, or remain the same.5

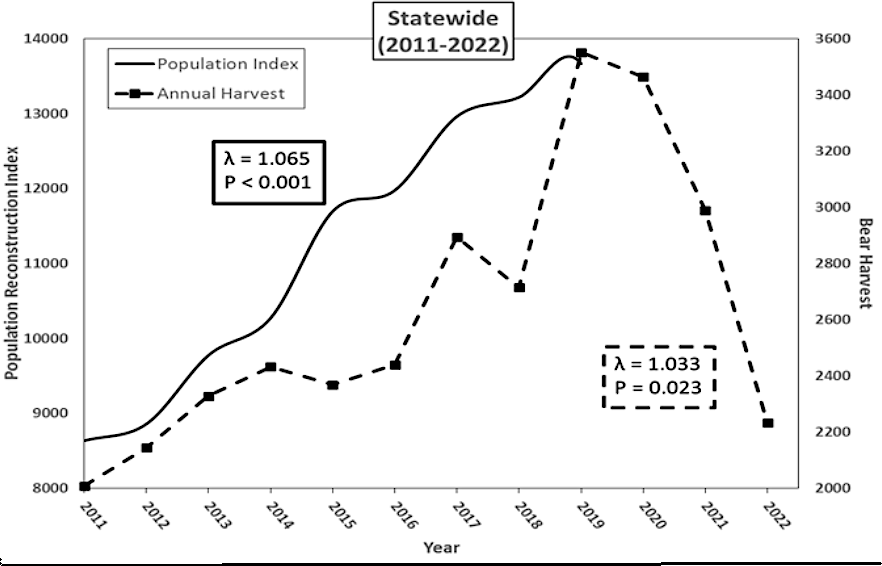

Bear management was so successful that the state agency began to seek population reductions starting in 2017, similar to how restoration of deer has led to a management focus to maintain the population rather than expand it in certain counties. Hunting seasons were expanded, to prevent an excessive population growth that would become troublesome for residents.

Hunting regulations require that successful bear hunters remove and send a premolar tooth to agency biologists. The teeth are used to determine the age of bears killed by hunters, and to calculate changes in the black bear population each year.

hunting is the primary management tool used to keep the black bear population in balance with the available habitat

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Virginia Bear

Management Plan 2023-2032 (Figure 14) and Virginia 2025–2026 Black Bear Harvest

The population has grown from 1,000 black bears at the start of the 1900's to 18,000-20,000 bears in 2021. What is now called the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources considers the bear population to be "robust." The 2020-21 harvest of 3,464 black bears was the second highest in the history of the state, exceeded only by the harvest a year earlier.

By 2022-2023, only 2,232 bears were killed during the bear hunting seasons. The decline was expected, since populations had been reduced after firearms season expansions in 2017 and 2019. A good acorn crop also made it harder for hunters to encounter bears. An outbreak of sarcoptic mange, a skin disease, had temporarily reduced the population in the northwestern counties.6

Reforestation and state-led wildlife management programs have been so successful at recovering the black bear population that they are now spreading into suburban areas, even taking dips in swimming pools. A bear specialist commented in 2023:7

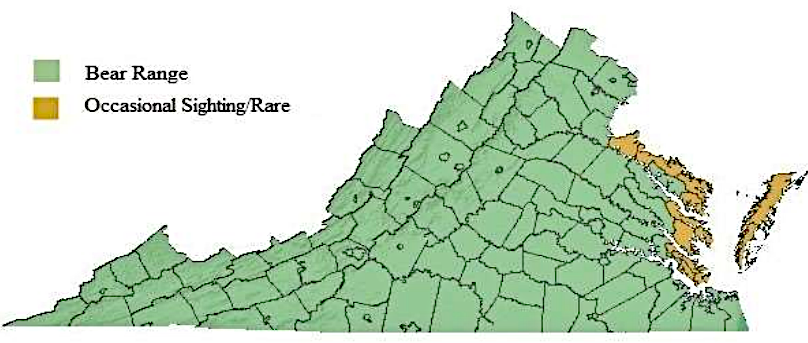

The willingness of young black bears to migrate into developed residential areas in the search for territory not already claimed by an adult was revealed clearly in 2024. A bear was killed by a car on I-395 in Arlington County at the Pentagon City/Reagan National Airport exit on June 15, 2024. Multiple bear sighting had been reported in the area, including one near Arlington National Cemetery.

The Animal Welfare League of Arlington warned residents not to be too ambitious in trying to take pictures when bears wandered through suburban areas, because they were wild animals and a potential hazard. The group noted:8

the expanding black bear population has expanded their range into suburbia

Source: jjjj56cp, bear on deck-- through the doors

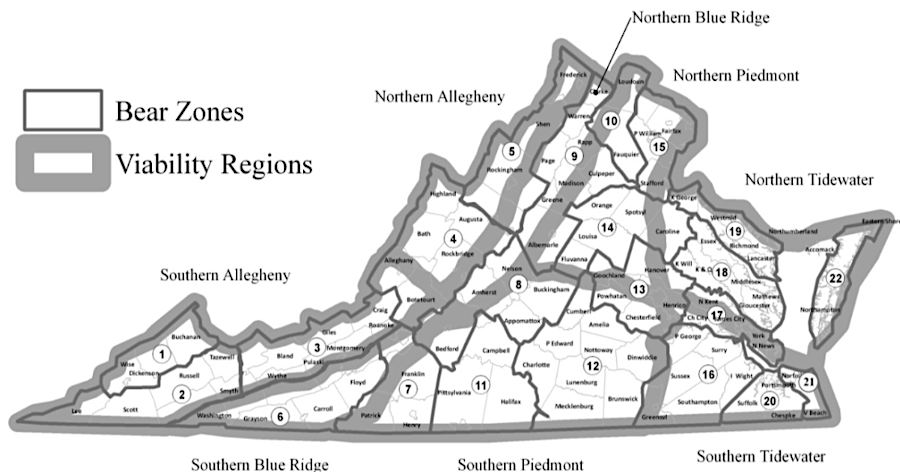

The Virginia Black Bear Management Plan (2023–2032) identified eight "viability regions" for managing bear populations, separate from the bear zones defined for hunting regulations. A management goal was to maintain a viable bear population within each of Virginia's physiographic provinces

The 2023–2032 plan increased emphasis on facilitating human-bear coexistence, but acknowledged that long-term population viability was more important even if it exceeded the cultural carrying capacity.

state wildlife managers have defined "viability regions" in addition to "bear zones" for hunting regulations

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Virginia Bear

Management Plan 2023-2032 (Figure 25)

In most areas of Virginia, residents have been tolerant of the expanding black bear population and established a leave-each-other-alone approach to large predators passing through back yards. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources manages a toll-free wildlife conflict helpline (855-571-9003) to respond when bear behavior threatens humans in some way, such as breaking into cars and houses where they smell food.

Less than 10 times a year, agency staff have to kill a nuisance bear that has become too habituated to humans. More often, state officials issue a "kill permit" to farmers who are losing an excessive amount of crops and wildlife to bears. Of the 236 kill permits issued in 2024, only 16 were to remove bears in residential areas.

nd animal control officials do not routinely capture and relocate bears in Virginia, because all of the suitable habitat away from human developments is already occupied by other bears. Relocating "Elden" from Herndon in 2025 was an exception, triggered by the publicity spectacle and an assessment that the bear was likely to continue to wandering through DC-area suburbs raher than move into a rural area.

Breaking-and-entering black bears are a common problem in Virginia. Attractants such as food smells, such as pet food left out for dogs and cats, invite bears to enter structures. One simple solution for homeowners is to place a bowl of ammonia next to doors and windows; bears find that odor of ammonia to be unpleasant.

Bearwise basics for residents in bear habitat are:9

In Montana and other western states, grizzly bears are expanding from the remote high country into valleys with houses. There are no grizzlies in Virginia today and little possibility of them migrating here anytime soon, but that species creates a different level of risk. Confrontations with grizzlies are more dangerous than interactions with black bears. In western states and Canada humans are being killed and mauled annually by grizzlies, and dangerous bears are being killed in response. People with children are purchasing guard dogs that were raised previously to protect just livestock.10

by 2021, black bears still had not returned to the Eastern Shore

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, 2023-2032 Virginia Bear Management Plan (draft) (Figure 7)

Source: Wildlife Center of Virginia, Preparing Orphaned Bear Cubs to Be Returned to the Wild