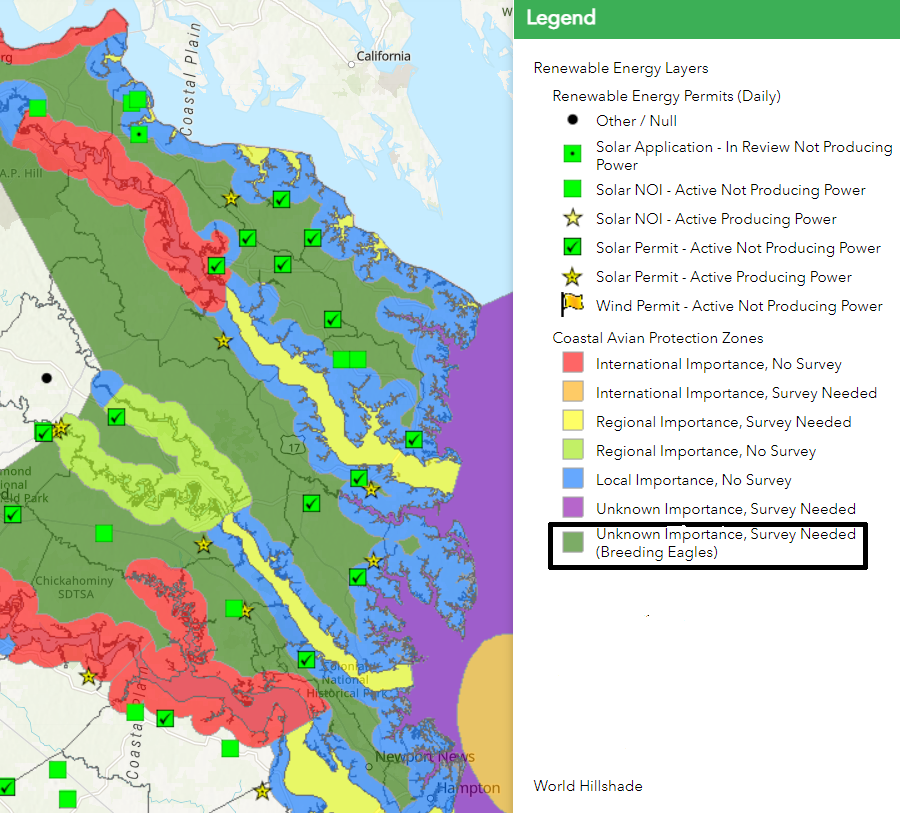

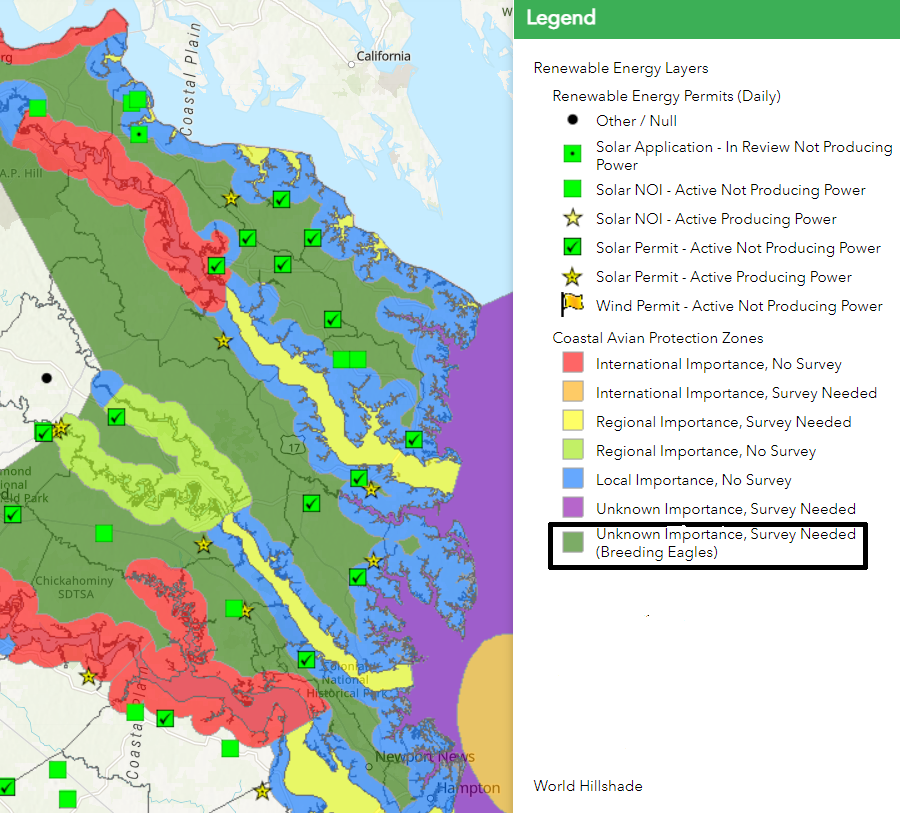

state agencies consider eagle nesting sites when issuing permits for renewable energy projects

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Environmental Data Mapper

state agencies consider eagle nesting sites when issuing permits for renewable energy projects

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Environmental Data Mapper

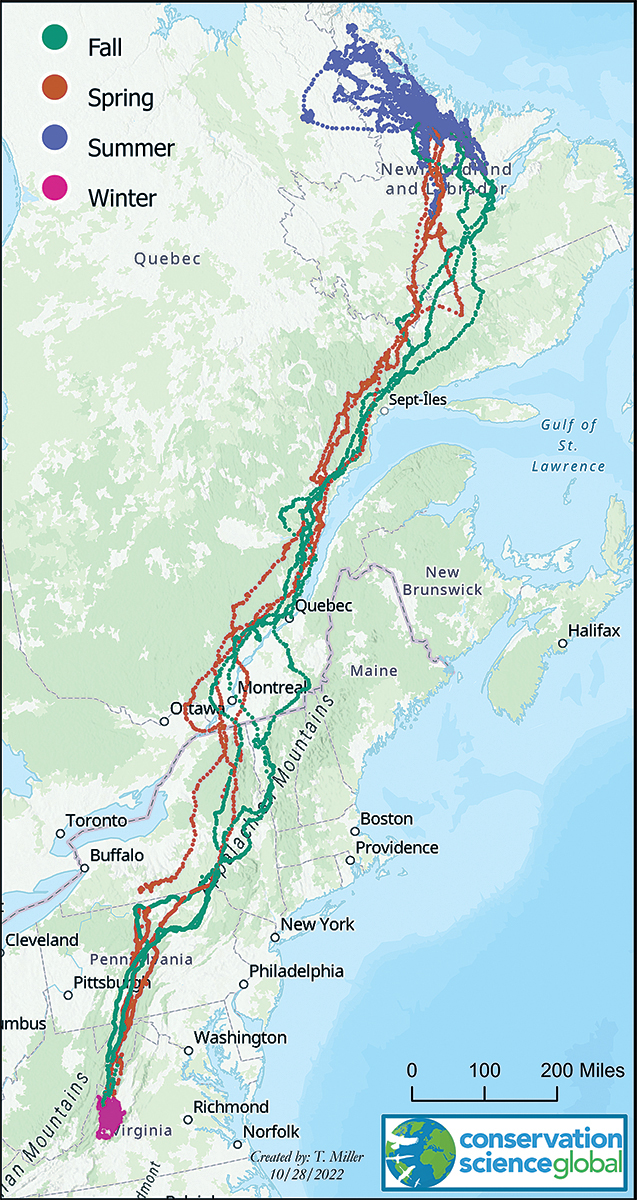

Golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) migrate through Virginia, primarily along the edge of the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Front. Tracking with GPS transmitters starting in 2009 revealed that golden eagles which breed in northeastern Canada migrate through Pennsylvania and winter in Virginia in the Appalachians.

Bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), a separate species, nest and live all year within the state.1

Today, the Chesapeake Bay has the densest breeding population of bald eagles in the United States outside of Alaska. The Potomac River between the Route 301 bridge and Reagan National Airport is a "bald eagle concentration area," with plenty of fish to eat and shoreline trees that provide excellent habitat for nesting.2

On February 1, 1969, Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge was established to protect the habitat and eagles nesting along the Potomac River in Fairfax County. It was the first Federal refuge established for the protection of an endangered species. It includes the 207-acre tidal freshwater "Great Marsh" with a large Great Blue Heron rookery.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service facility was renamed Elizabeth Hartwell Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge in 2006, to honor a woman who started as a "garden club housewife" and ended up as the "Eagle Lady." She was responsible for the peninsular ending up as a wildlife refuge instead of the proposed Kings Landing development, with 20,000 residents.3

bald eagles hunt primarily for fish, but will scavenge from deer carcasses as well

Source: National Park Service, Design for the Verso of the Great Seal of the United States

The bald eagle population in the Lower 48 states has rebounded since being classified as an endangered species in 1967. The species was reclassified from "endangered" to "threatened" in 1995. It was removed from the Threatened and Endangered (T&E) Species list in 2007, though it still receives special attention from the 1940 Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

The two greatest threats to bald eagles in the 1960's were the loss of habitat and the impacts of DDT. Today, the greatest threat is chronic lead poisoning.

The lead is ingested when eagles feed on deer which have been killed by hunters. Lead bullet fragments are in the deer carcasses, and the eagles scavenge the remains during the winter when other food is scarce.

Though the lead poisoning reduces the population of bald eagles by about 4%, it is a sign of the success in the recovery of the species. As noted by a spokesperson for the Wildlife Center of Virginia in Waynesboro:4

The successful population rebound of bald eagles along the Chesapeake Bay, now 3,000 pairs creating the largest concentration of eagles in the lower 48 states, may have peaked. All the suitable habitat is occupied during the breeding season. Nesting success has dropped, as adult males are forced to spend time defending the nest rather than gathering food.

By 2023, eagles were:5

The bald eagle has been a national symbol since it was chosen for the Great Seal of the United States in 1782. The US Congress did not formally designate any species as the "national bird" until the bald eagle was given that label at the end of 2024. The oak had been designated as the official National Tree in 2004, and the bison/buffalo was designated as the national mammal in 2016.6

the US Congress chose the eagle for the Great Seal in 1782

Source: National Archives, Design for the Verso of the Great Seal of the United States

bald eagles have a white head and tail; golden eagles do not

Source: Virginia State Parks, Bald eagle in flight at Chippokes State Park and WR - Golden Eagle 8

path of a golden eagle with a GPS tracker between 2012-2015 that summered in Labrador and wintered in Highland County

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Discovering Virginia’s Golden Eagles