alewife are anadromous, spawning in Virginia's freshwater streams and living as adults in saltwater

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Alewife

alewife are anadromous, spawning in Virginia's freshwater streams and living as adults in saltwater

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Alewife

Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis), American shad (Alosa sapidissima), and hickory shad (Alosa mediocris) are anadromous fish. Adults migrate annually from the salty Atlantic Ocean into Tidewater rivers to spawn in freshwater.

The two herring species are so hard to distinguish in the water that they are commonly called "river herring." Alewife herring start spawning in late February, a month earlier than blueback herring. They migrate downstream after spawning, returning multiple times from the ocean to initiate a new generation. The young juveniles remain in freshwater streams until late Fall, when they swim downstream to the ocean or, in some cases, spend their first winter in the brackish water of the Chesapeake Bay.

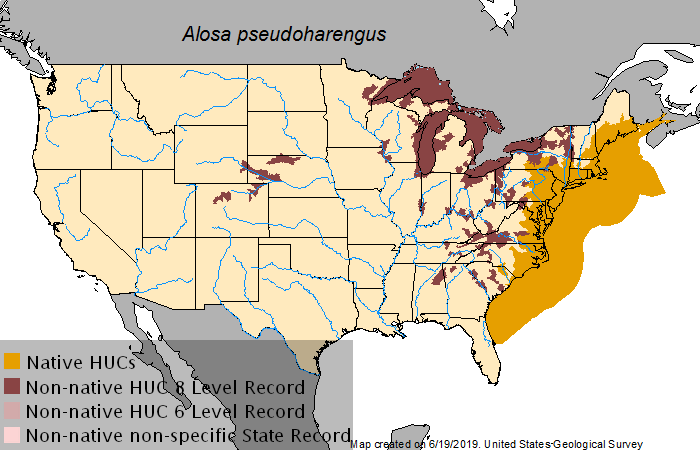

Alewife and blueback herring can tolerate freshwater throughout their entire lives. Fishery managers have established reproducing populations in freshwater rivers, the Great Lakes, and reservoirs.1

fisheries managers have extended the distribution of alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) to exclusively freshwater streams and lakes ("HUC"="hydrologic unit code")

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), NAS - Nonindigenous Aquatic Species, Alosa pseudoharengus (Wilson, 1811)

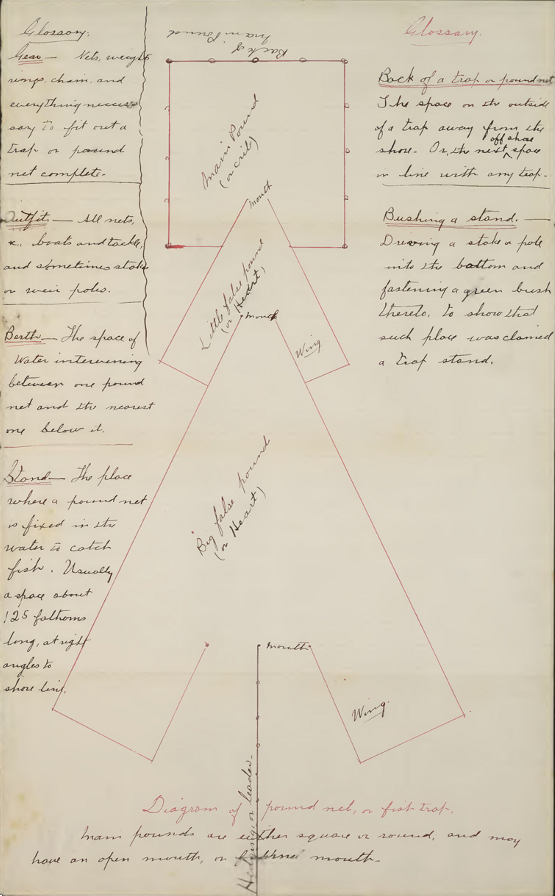

Native Americans fished for river herring and shad using a variety of techniques. English colonists settling at Roanoke Island observed Native Americans using "pound nets," which trapped fish as they swam underwater and provided a high amount of protein with minimal effort (other than installing and maintaining the net).

Colonists adopted the same technique, as well as casting nets from boats or the shoreline to intercept schools of migrating fish. In 1608, when John Smith explored up the Potomac River, he reported that fish were plentiful but the English lacked nets - so they tried to catch fish jumping out of the water by swinging an iron frying pan.

pound net used in 1900, placed in Potomac River so fish swim in (at bottom) and get trapped

Source: Library of Virginia, Out of the Box, Don't Bush My Stand

George Washington's most profitable activity at Mount Vernon was his fishing operation. Claims that the shad run up the Delaware River in 1778 kept soldiers camped at Valley Forge from starving may be overstated, but once the migration started the fish must have been a welcome food source before the troops marched away in June.

Source: YouTube, George Washington's Mount Vernon: Colonial Angling

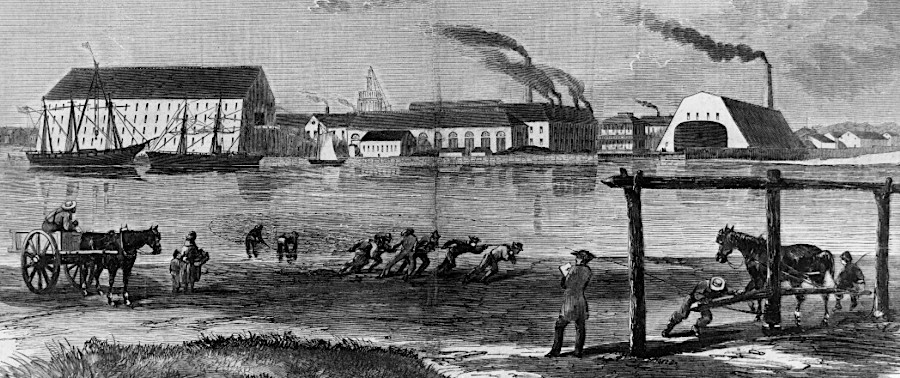

In the 1830's, fishermen caught 22,500,000 shad and 750,000,000 herring annually in the Potomac River. The fish were salted in barrels, then transported by wagon and ship to distant markets.

fishing with a net for shad in the Potomac River at the Washington Navy Yard in 1861

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, The Washington Navy Yard, with Shad Fishers in the Foreground"

Starting in 1949, the Wakefield Ruritan Club's annual "shad plank" in Sussex County was a traditional political ritual each April. Shad were nailed to hardwood planks and cooked over an open flame while politicians and reporters mingled, drank, and gossiped.

The participants were all white male Democrats until the early 1970's, when Virginia's political parties aligned with the national parties and conservative Republicans were allowed to participate. In 1977, when State Senator L. Douglas Wilder was a candidate for Lieutenant Governor, blacks and women were finally invited to the event.

The significance of the Shad Planking declined among Democratic candidates. In 2009, Democratic candidate Creigh Deeds bypassed the opportunity to speak at what was once a "must-do" for statewide candidates. At that time, the shad were still abundant enough to be featured at an event with over 1,000 people.2

the Shad Planking in Wakefield each April was a traditional political gathering for the last half of the 20th Century

Source: Wikipedia, Shad Planking

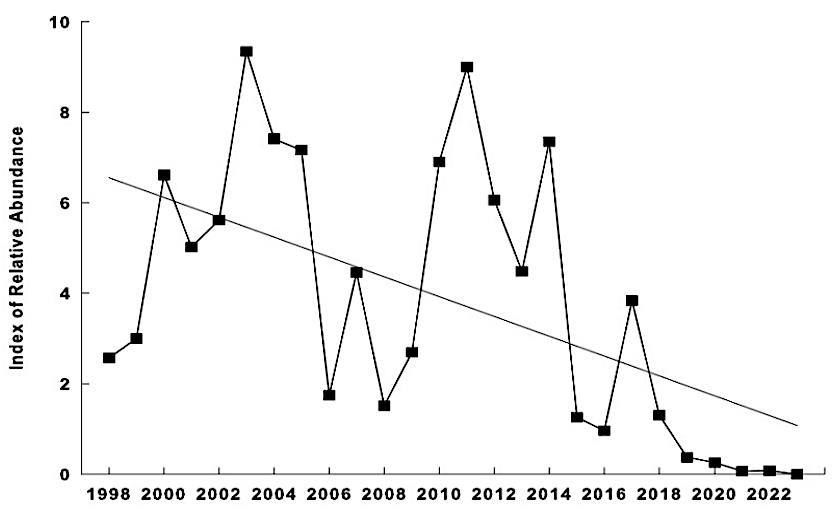

The numbers of what were once very common anadromous fish in Virginia have dropped dramatically due to overfishing, habitat destruction, and limited access to breeding sites due to dam construction.

Populations are measured by a "catch index" - how many of fish are caught per net, per day. Since sampling started in 1998, the catch index for shad in the James River has ranged from 9.3 fish caught per net per day (in 2003) to 1.2 (in 2015). In the York River, the catch index dropped from 14.7 (in 1998) to 1.9 (in 2015). In the Rappahannock River, the low catch index of 1.3 (in 1999) climbed to a high of 8.7 (in 2014), then declined to 5.1 (in 2015).

A fish ecologist suggested that the variation was not a reflection of success or failure in efforts to restore shad. Instead, the numbers had been reduced dramatically from the typical population before the arrival of English colonists 400 years ago, and changes in the catch index were not significant compared to the massive reduction from the original base population:3

Native Americans make fishhooks by carving bone

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Bone Fish Hook

Efforts to increase shad populations include banning commercial harvest in 1994, removing dams that have blocked shad from migrating upstream to spawning habitat in Virginia rivers, and raising shad in hatcheries and releasing the young fish upstream of the old dams to start new populations that might return to the stocked sites.

The Mattaponi Tribe opened a hatchery to raise shad in 1917. With state support, a new hatchery was built in 2000. The Mattaponi estimated that squeezing the "milt" (sperm) from a male shad onto the eggs increased fertilization success by 60%.

The Pamunkey Tribe opened their hachery in 1918. It closed in the 1940's, and the tribe then hatched shad by using tidal boxes. In 1989, with Federal funding, a new indoor hatchery was completed. The Commonwealth of Virginia provided support as well, and the hatchery was expanded in 1992 and again in 1994. In 1998, the Pamunkey begain marking hatchery-raised fish with Oxytetracyclin (OTC) so they could be identified when caught.

American shad (Alosa sapidissima)

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, American Shad (by Duane Raver)

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission has established a moratorium on even recreational fishing for river herring:4

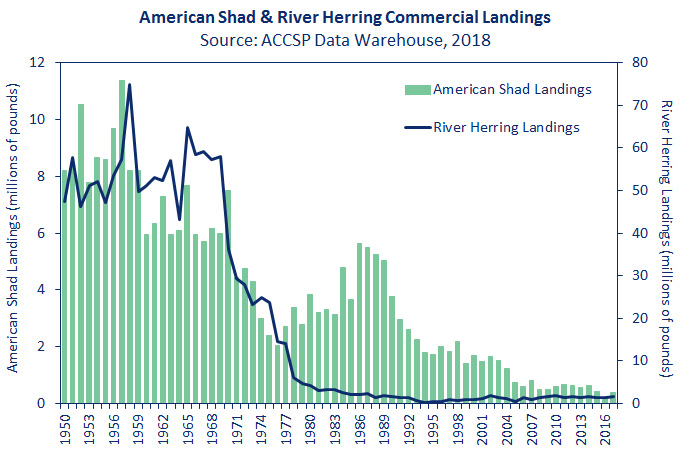

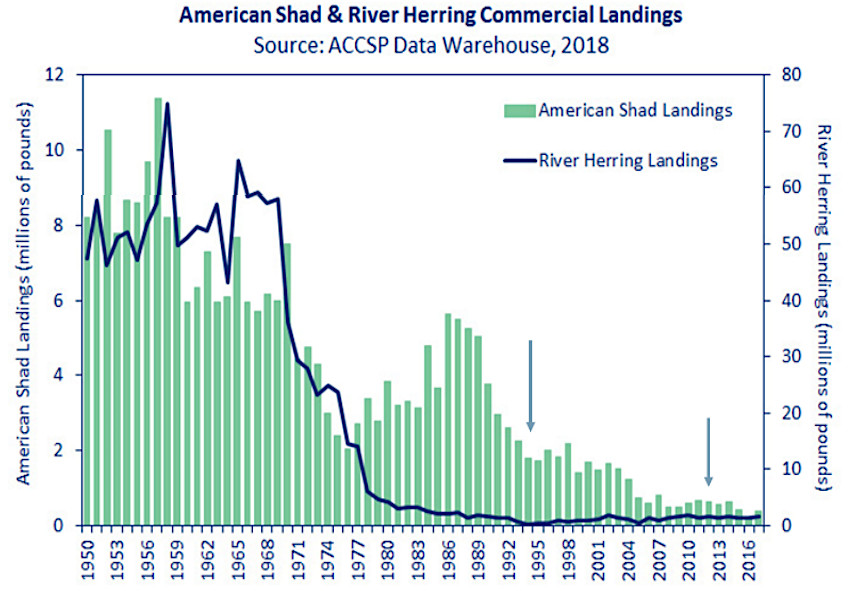

Maryland closed its commercial shad fishery in 1980. In 1982, the Potomac River Fisheries Commission (a joint program of both states) banned commercial fishing of shad in the Potomac River. It took Virginia until 1994 to end commercial fishing for shad in the state's portion of the Chesapeake Bay and inland waters. The James River shad harvest in 1993 was only 3,100 pounds, compared to 1 million pounds two decades earlier.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) manages shad and river herring in the Atlantic Ocean. It closed the at-sea fishery for shad in 2005. The 2007 coastwide stock assessment will be updated in 2020 for American shad. The 2007 report:5

excessive harvest and habitat alteration dramatically reduced shad/river herring populations, forcing an end to most commercial harvest

Source: Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, Shad and River Herring

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) rejected a petition to add alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) and blueback Herring (Alosa aestivalis) to the endangered species list in 2013. At the time, the harvest in the Chesapeake Bay had dropped 99% compared to the average in 1950-1970.

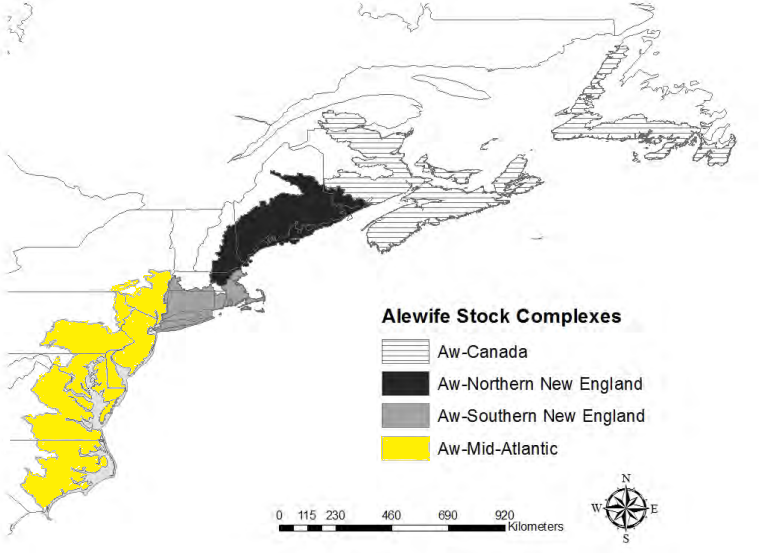

The Natural Resources Defense Council and Earthjustice appealed the reject, and in 2017 a Federal judge required the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to reconsider the petition. A 2019 species status review determined that there were four "distinct population segments" of alewife on the East Coast, with the most-southern segment living between the Hudson River and the Alligator River in North Carolina.

one of the four "distinct population segments" of alewife on the East Coast swims in Virginia waters

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Status Review Report: Alewife and Blueback Herring (2019)

There are five distinct population segments of blueback herring. The middle population lives between the Connecticut River and the Neuse River in North Carolina.

In the status review, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration again declined to list those two species as "threatened." The Federal agency concluded that there was a 30% moderate risk of extinction for the distinct population segment of alewife that swim in Virginia waters. For blueback herring, there was a 30% moderate risk and a 1% high risk of extinction. The survival of the species was expected because:6

The latest report from the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission remained pessimistic about river herring:7

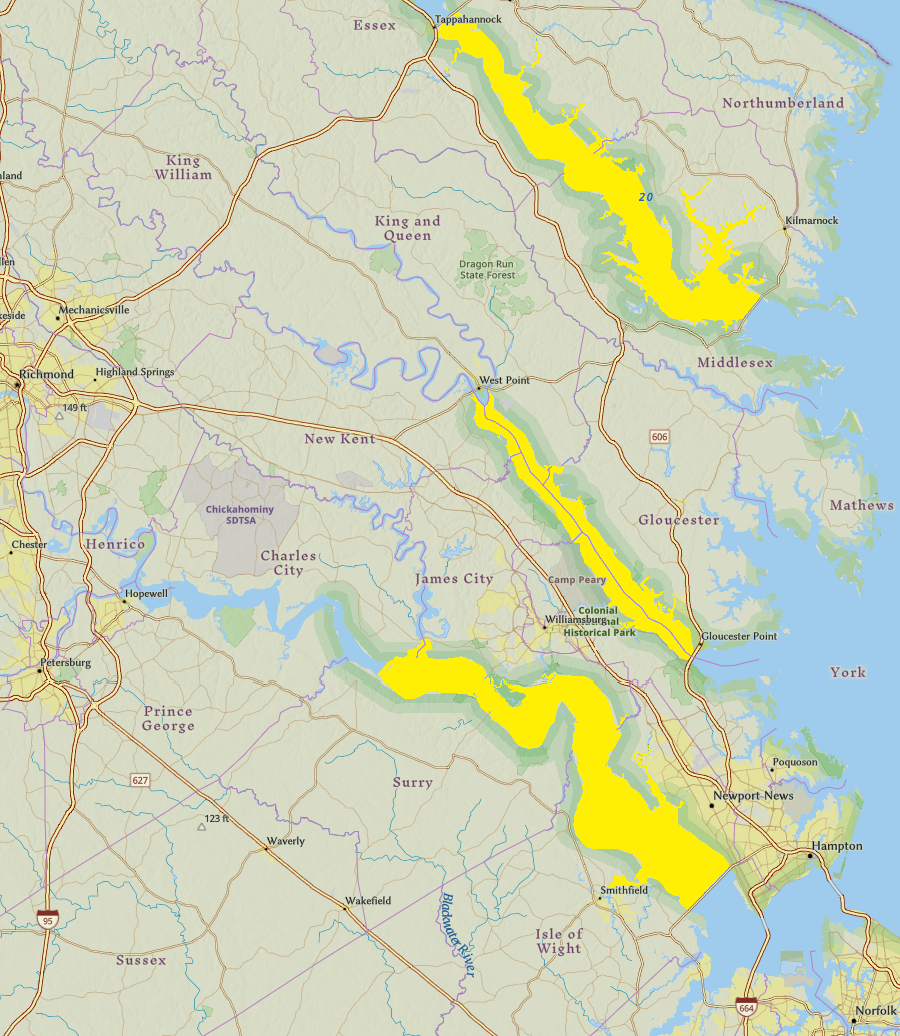

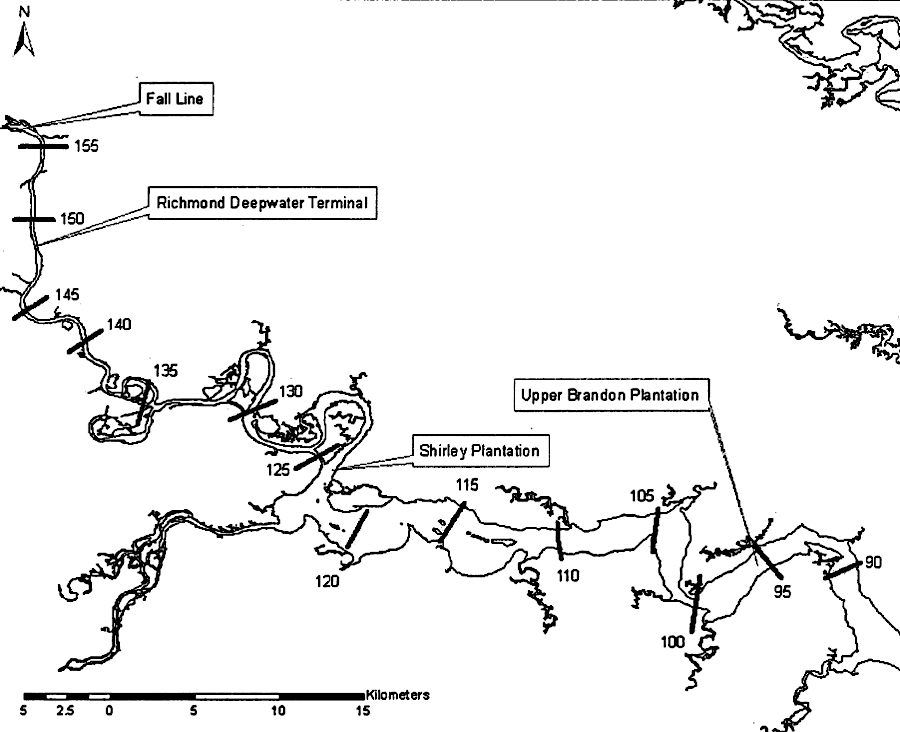

Commercial "bycatch" harvest of the American shad in the Chesapeake Bay and some Virginia rivers waters is permitted, but prohibited in the Atlantic Ocean. In the spring, the shad migrate up to the Fall Line, and recreational fishing is permitted above the bycatch boundary line defined for the James, York, and Rappahannock rivers.8

bycatch area where commercial fishermen are authorized to possess some American shad

Map Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin (ICPRB) initiated a restoration effort for Potomac River shad in 1995, and 18 million shad fry raised at the Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery were stocked in the river. In 2000, 10 miles of fresh water habitat was made available by creating a fish passage through the Brookmont Dam at Little Falls.

cutting a notch (red circle) in Brookmont Dam at Little Falls in 2000 opened 10 miles of habitat upstream

Source: GoogleMaps

The Potomac River population recovered enough to become an egg source for restocking the Rappahannock River. Adult shad captured in the Potomac River near Fort Belvoir and Mount Vernon supplied eggs for restocking 48 million shad fry in the Rappahannock River between 2002-2014. To replace the adults harvested for the egg collection, another four million shad fry were placed in the Potomac River. In 2012, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission declared shad in the Potomac River were a recovered and sustainable fishery.9

In contrast, efforts to restore shad by stocking hatchery-raised fish have failed elsewhere in Virginia. The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries invested in placing young shad in streams above dams that were going to be removed, to initiate a migrating population even while barriers were till in place and jump-start a recovery.

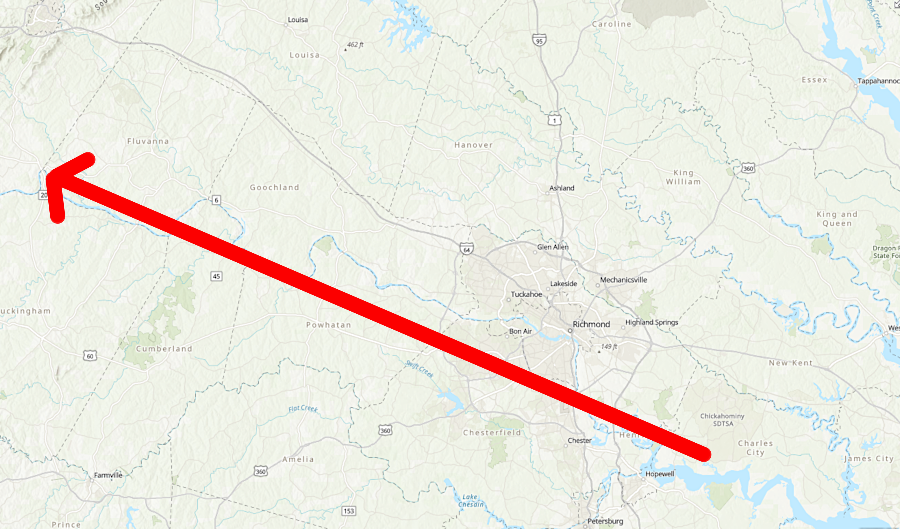

Shad were also stocked in the James River upstream of the fish ladder at Bosher's Dam in Richmond. Young fish raised at the US Fish and Wildlife Service Harrison Lake Fish Hatchery in Charles City County were trucked to Scottsville for release.

hatchery-raised juvenile American shad were transported upstream to Scottsville, but the restoration program failed to increase populations in the James River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Plans for releasing 10 million shad a year were constrained by the limited availability of female shad to provide eggs for the hatchery. Eggs from adult shad already migrating in the James River were preferred, but the hatchery supplemented them with eggs from shad migrating in the Pamunkey River and eventually the Potomac River. In the peak year (2000), 7 million fish were stocked.

Though in theory the re-stocking should have led to an increased population, the results were unsatisfactory. The Department of Game and Inland Fisheries decided in 2017 that the costs exceeded the benefits and ended the program. A fisheries biologist summed up the situation:10

In 2020, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission defined the shad population as "depleted." The construction of dams had blocked 40% of the spawning habitat, and only in the Rappahannock and York rivers were shad reproducing fast enough to sustain the existing low population numbers. Hatchery operations, limits on commercial fishing, and dam removal did not stimulate an expansion of the population.

One theory was that the invasive blue catfish and snakeheads were eating the young shad within the Chesapeake Bay, while other predators were eating the fish in the Atlantic Ocean. "Bycatch" of shad by commercial fishing boats targeting other species could also be a factor. Dolphins were predators, to such an extent that shad have evolved sound receptors to avoid dolphins that hunt using echolocation.11

In 2021, the shad population in the James River had dropped to the lowest level ever recorded. Less than 10,000 were thought to have reached Richmond, so the value of the Bosher's Dam fish passage project was diminished. The 1994 moratorium on commercial and recreational fishing, 25 years of restocking shad from a hatchery until 2017, and removing dams to increase access to upstream habitat had not led to population recovery.

fish passage projects have not led to shad recovery in the James River

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Shad Migration at Conowingo Dam (photo by Will Parson)

Threats to shad were numerous. The loss of underwater grass beds made juvenile shad more vulnerable to predators. Water intakes entrapped juveniles, while warmer water temperatures and industrial pollution in the river were thought to impact early development before young shad migrated to the ocean.

The head of the James River Association called for development of an emergency recovery plan, especially since their ocean life history was poorly known and by-catch from the mackerel fishery might be impacting shad populations. He declared:12

shad populations have plummeted

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), A Framework for the Recovery of American Shad (Alosa sapidissima) in the James River, Virginia (November 2023)

A 2023 report from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science provided a framework for recovery of American Shad in the James River tha would initially cost $2.6 million. The decline of shad populations had multiple causes, but a major factor was that the once-rocky bottom of the James River in Tidewater was now covered with silt. The silt coating blocked shad from laying eggs that would hatch successfully.

Recommended actions including research to identify how to reduce egg mortality caused by water intake facilities, plus re-starting the program to raise shad in hatcheries for release in the James River. The shad hatchery program had been cancelled in 2017, after biologists concluded that hatchery-raised shad were not increasing poplations in the wild. The 2023 study concluded that the remaining stock was largely due to previous hatchery input; spawning by wild shad was not expanding the population.

The report also recommended research to determine the impact of warming river temperatures. Shad begin migrating upstream when water reaches 41°F, with the peak of movement when the temperature is between 50-55°F. It is possible that climate change has caused migration to occur sooner, when food resources may not be plentiful yet.13

In 2024 the Virginia Coastal Conservation Association petitioned the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) to limit the harvest of shad by recreational anglers to just 10 fish per day. The proposal lacked scientific research to justify the limit, other than the obvious decline in the four species of shad and herring in Virginia, and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) did not support imposing a limit. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission rejected the petition, but the Virginia Institute of Marine Science agreed to start monitoring hickory shad populations in 2025.14

shad once spawned heavily in the James River upstream of Shirley Plantation to just above the fall line

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), A Framework for the Recovery of American Shad (Alosa sapidissima) in the James River, Virginia – November 2023 (Figure 2)

decline of the shad population in the James River

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), A Framework for the Recovery of American Shad (Alosa sapidissima) in the James River, Virginia – November 2023 (Figure 7)

the Roanoke colonists observed how Native Americans used pound nets to catch herring, shad, and other types of fish

Source: Newberry Library, Their Manner of Fishynge in Virginia (by Theodor de Bry, 1590)