eelgrass (Zostera marina) recovery has begun along the Atlantic Ocean side of the Easten Shore

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Eelgrass

eelgrass (Zostera marina) recovery has begun along the Atlantic Ocean side of the Easten Shore

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Eelgrass

Though forests and pastures are the most obvious vegetation to "landlubbers" in Virginia, the underwater grasses in the Chesapeake Bay are being monitored very closely by those trying to measure if we are saving or losing the Chesapeake Bay.

Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) mapped at Cape Charles

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Bay Grasses (SAV) in Chesapeake Bay and Delmarva Peninsula Coastal Bays

The 17 million people who live in the Chesapeake Bay watershed have upset the natural balance through a number of different stressors. Life adapts over thousands of years of time, but in the last 400 years, the impacts of increased urbanization have dramatically lowered the productivity and biodiversity of the Chesapeake Bay, especially the Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV).

Restoring the underwater grass is essential for restoring the crabs, bay scallops, oysters, and fish populations. The cultural patterns that were based on harvesting the food from the Chesapeake Bay cannot be sustained without recovery at the bottom of the food chain.

Grazing animals on land depend upon vegetation to provide food. Cattle eat hay, deer browse on branch tips, caterpillars chew on leaves. Similarly, many of the animals in the Chesapeake Bay depend upon the submerged vegetation; the food chain starts with vegetation at the bottom. In the water, various animals feed on the invertebrates that eat the Submerged Aquatic Vegetation, comparable to the way land-based birds eat caterpillars that eat leaves.

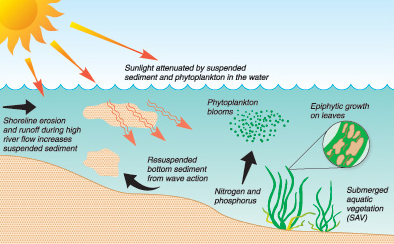

Algae is a source of food, but after it dies it decays and sucks oxygen out of the water. Excessive growth of algae, such as phytoplankton blooms, is followed by masses of decaying matter on the bottom of the bay, creating "dead zones" with inadequate levels of dissolved oxygen. Even Submerged Aquatic Vegetation, which generates oxygen in the daytime, needs sufficient levels of dissolved oxygen in the water at night to fuel its normal metabolic operations.

SAV is killed and submerged lands become underwater deserts when sediments block sunlight, or when oxygen levels drop to zero

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Synthesis of USGS Science for the Chesapeake Bay Ecosystem and Implications for Environmental Management

Without underwater pastures in the water, aquatic invertebrates have little food or shelter. Without the invertebrates in the food chain, estuaries no longer serve as nurseries for fish that feed on the invertebrates. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service:1

The recovery of the crab and rockfish populations will be enhanced if they have more food. The 2014 Chesapeake Bay Agreement included a specific outcome for Submerged Aquatic Vegetation:2

A key species of Submerged Aquatic Vegetation, eelgrass (Zostera marina), disappeared from the Atlantic Ocean side of the Chesapeake Bay after a 1933 hurricane. Prior to that event, a mold had already spread through the grass beds and disease had dramatically reduced the eelgrass. After the eelgrass disappeared and its sheltering habitat was no longer available, the bay scallop population plummeted.

In 1999, scientists noticed a patch of eelgrass had started to grow in a seaside bay. Seeds had naturally drifted to the site. The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) initiated a seed collection and replanting program to restore eelgrass in additional areas. Seeds collected in early summer by volunteers were kept in saltwater holding tanks until the Fall. Planting was easier than seed collection. The seeds were tossed off boats into the water, and sank naturally to the bottom.

Two decades of work for the Virginia Coast Reserve Long-Term Ecological Research project led to significant success:3

By 2025, seagrass had been restored across 14 square miles on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Eastern Shore. A University of Virginia professor noted:4

Seagrasses developed 70-100 million years ago, evolving from terrestrial grasses. They thrive in water at 60-68 degrees Fahrenheit, so warming temperatures are a threat. Summer peak temperatures are already reaching 82°F in the Chesapeake Bay, which is the upper limit for survival of eelgrass.5

pastures of eelgrass are essential for scallops, crabs, and fish

Source: National Park Service, Northeast Coastal and Barrier Network Species Spotlight: Eelgrass

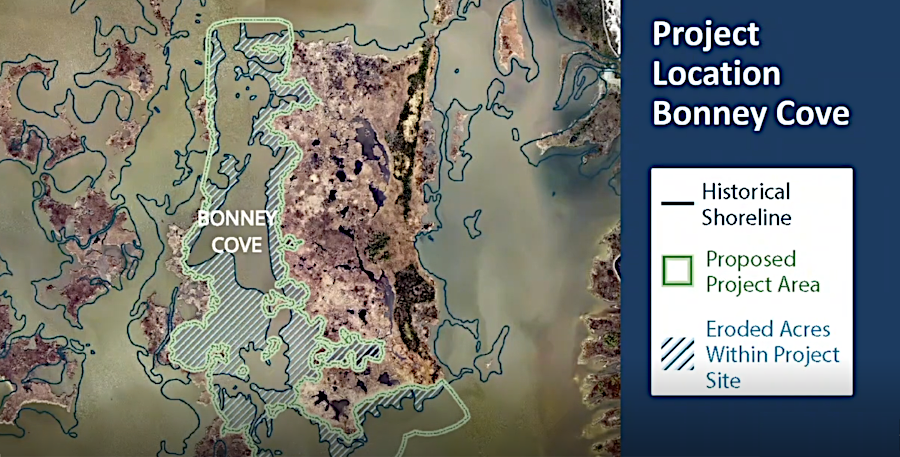

The City of Virginia Beach planned to restore Submerged Aquatic Vegetation in 47 acres of Bonney Cove in Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge. The city estimated that 70% of the underwater grasses - 2,000 acres of marshland - had disappeared; half of the open water was formerly marshland. City voters had approved a $567.5 million flood protection bond in 2021, and that bond included $31.4 million for the Bonney Cove project. The city also succeeded in getting additional grants for a project costing $46 million in total.

creating 50 acres of marshland in Bonney Cove was expected to reduce wind-tide flooding in Back Bay

Source: City of Virginia Beach, Marsh Restoration in Back Bay presentation to City Council May 27, 2025

The project involved creating 41 terraces, small islands that would interrupt the large stretch of open water and create sheltered underwater spaces for grasses to grow. Creating individual terraces rather than one block of land maximized the marsh edge where grasses would grow. In the end, there would be 13 acres of emergent marshlands, 14 acres of vegetated upland habitat, and 16 acres of submerged terrace habitat.

The terraces and grasses were expected to block some of the "wind-tide" effect, when southern winds pushed water from Currituck Sound up Back Bay and flooded developed properties along the shoreline.

About 260 acres of marshland have been lost within Bonney Cove; 50 acres of new marshland would be created by the project. The innovative approach to establish "green infrastructure" was preferred over two other alternatives: creating an artificial inlet to drain water into the Atlantic Ocean, or building an inverted siphon and pump station to remove excess water. The land above the surface created by 41 new terraces would be owned by the Commonwealth of Virginia, not the City of Virginia Beach or Back Back National Wildlife Refuge. However, the city would be responsible for maintaining the islands.

new terraces in Bonney Cove would provide shelterted habitat for growth of submerged aquatic vegetation

City of Virginia Beach, Marsh Restoration in Back Bay

Delays in getting the project approved cost the city an additional $9.9 million in grant funding. The Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) refused to approve a permit for use of submerged state-owned land because grasses had naturally returned on much of the bottom of Bonney Cove since the project was planned in 2020.

The city's project manager described the issue succinctly:6

The city's only options were to abandon the project or seek special legislation from the 2026 General Assembly directing the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to authorize the project.7

Source: City of Virginia Beach, Marsh Restoration in Back Bay presentation to City Council May 27, 2025