eroded streambanks at Scotts Run, between Great Falls and American Legion Bridge

(carrying excessive runoff from impervious surfaces at Tysons Corner)

Virginia has committed to "Save the Bay," by signing the Chesapeake Bay Agreement. In theory, enought actions will be completed by 2025 to restore the Bay, overcoming the damage from modern development and making the Bay closer to the rich ecological resource that John Smith saw in 1608.

Today, excessive sediment and excessive nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorous) from three sources are the main threats to the Bay. The three sources of nutrients are wastewater treatment plants (at the end of the sewer lines, processing what we flush), agricultural runoff (from fertilizer and manure in fields), and urban stormwater runoff (from parking lots and rooftops). Runoff, especially urban runoff, erodes the edges of creeks. The obvious effect: trees fall down. Less obviously, the sediment eroded away is dumped into the Potomac River and ultimately the Bay, smothering the bottom.

eroded streambanks at Scotts Run, between Great Falls and American Legion Bridge

(carrying excessive runoff from impervious surfaces at Tysons Corner)

Wastewater plants have pipes that dump their treated water into creeks/rivers, so those "point sources" are regulated through National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits under the Clean Water Act. Agricultural and urban runoff does not enter creeks through just a few specific locations, so the runoff is called "non-point" pollution - and that pollution is not regulated through permits.

wastewater treatment plant at Lorton (what students flush on George Mason University's Fairfax campus ends up here, within less than a day)

Northern Virginia did not start treating sewage waste until the mid-1950's, but all sewers are connected to high-tech wastewater treatment plants now. Those plants have been upgraded through a massive infusion of Federal funding, plus higher user fees to customers. The nitrates/nitrites we ate with our vegetables/preserved bacon, and other sources of nitrogen that we sent down the garbage disposal/toilets, is converted into harmless N2 gas here through bacterial action in massive concrete tanks. It's been expensive, but pollution from that source has been limited through the use of the best available control technology.

Non-point runoff is harder to capture and process, however. There are no treatment plants at the edge of each horse farm in Loudoun or Great Falls, and there are no treatment plants at the end of the storm sewer systems. The solution to that pollution: stop it from entering the creeks, rather than pump all the creek water through an expensive filtering system downstream. (If you hear someone suggest that solution, ask them to calculate the cost of processing all the water in all the creeks... including how many power plants would be required to generate the energy required to run the facilities.)

temporary silt fence at construction site, installed until vegetation can be established to hold soil particles and minimize erosion

(capable of capturing more than half of construction runoff before it enters a creek... but even if silt fences are installed and maintained well, much sediment will get into the creek)

temporary silt fence, not maintained...

One low-cost way to reduce non-point pollution to is to establish buffer zones along all perennial streams (those that typically flow throughout the year), to prevent pollution from entering creeks that lead to the Chesapeake Bay. Sounds simple, right? Protect the shoreline of creeks, and let the natural vegetation in the buffer zone capture sediments in runoff before the particles fall into the creek.

Runoff would be slowed down, soaking into the ground., Some water would be absorbed by the vegetation, instead of racing rapidly from farm field or road into the creeks and causing a rapid spike in flow that erodes the banks.

Bull Run - effect of erosion downstream from Clifton and Pope's Head Creek

Much of the excessive nitrogen and phosphorous polluting the streams would be intercepted along with the sediment particles. The buffer might be fertilized slightly, enhancing growth of streamside vegetation, and the excessive nutrients and sediment would not reach the Bay. Let Mother Nature and Father Time do the work of cleaning urban or agricultural runoff, using natural processes in the buffer. Saving a few trees is far cheaper than building a new treatment system to process stormwater, to ensure nutrient-rich runoff does not kill the Bay.

So the state passed Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area Designation and Management Regulations ("Ches Bay regs"), and required that the regulations be enforced by those jurisdictions designated by the state as part of "Tidewater." Not all counties/cities in the watershed were included - Loudoun County and others upstream, with no shoreline affected by the rise and fall of the tides, are not required to comply with the Ches Bay regs.

The Ches Bay regs required originally that lands at, or near, the shoreline, be protected - but "shoreline" was not defined. The state then modified the Ches Bay regs to state that a 100-foot wide Resource Protection Area (RPA) buffer is required on each side of a perennial stream.

But those 100-foot buffer strips reduce the potential for building houses, or extra houses, on many parcels. Not surprisingly, landowners have contested the designation of no-build strips, mostly by contesting if a stream is "perennial." Since streams that are only intermittent (flowing for just a portion of the year) do not have a buffer, there's an incentive for property owners to classify their streams between July and early September during major droughts. County officials have to make a judgment call, adjusting for abnormal rainfall, if they want to argue that a dry streambed is in fact a perennial stream.

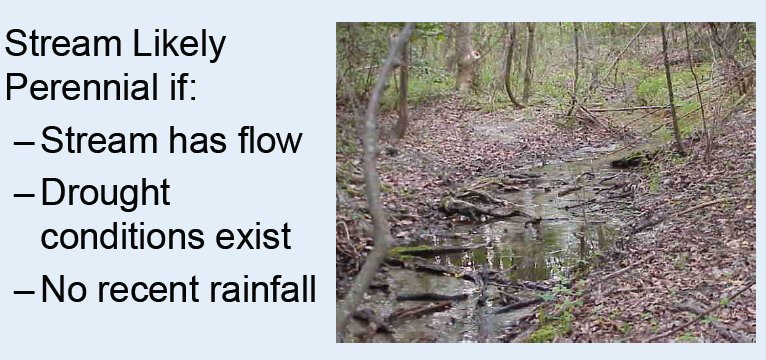

clues for classifying a perennial stream

(when weather conditions are normal, or drier than normal, and stream is still flowing in August... it's probably perennial)

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation

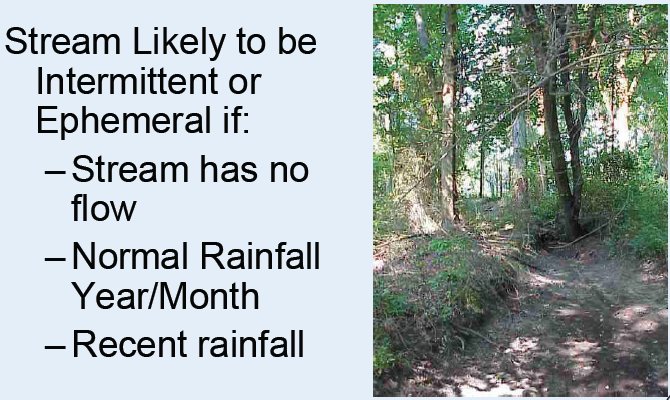

clues for classifying an intermittent stream

(when weather conditions are normal, or wetter than normal, and stream is not flowing in Spring... it's probably intermittent -

even though you may see a large stream channel, carved by significant but intermittent water flow)

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation

Read: