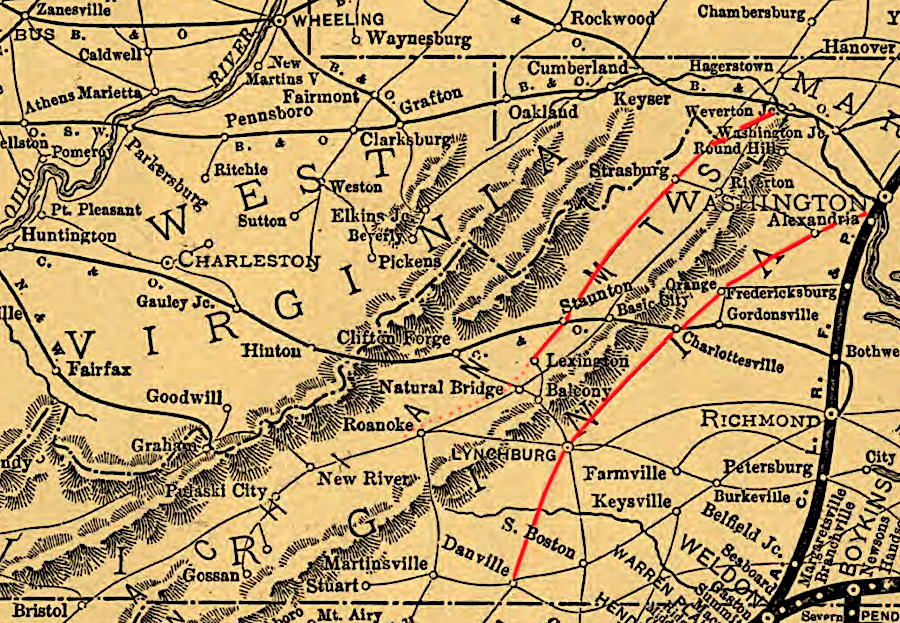

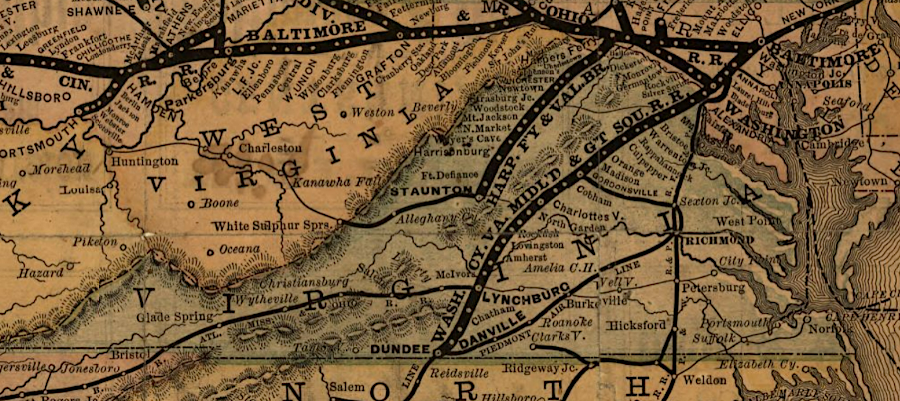

at its peak, the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad controlled track to Staunton and Danville

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road with its branches and connections (1878)

at its peak, the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad controlled track to Staunton and Danville

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road with its branches and connections (1878)

The Virginia General Assembly issued a charter for the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad on March 8, 1827. The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad ultimately became one of three mainline systems linking Chicago to the East Coast, together with the Pennsylvania and New York Central railroads.

Merchants in Baltimore invested in the railroad because they anticipated how the Erie Canal would draw western trade to New York City, Pennsylvania’s canal system would pull trade to Philadelphia, and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal would increase business at Georgetown and Alexandria on the Potomac River. To be a competitive port for products coming from the Ohio River Valley, Baltimore needed to construct its own transportation network through the Allegheny Front to the Ohio River.

A canal was not a feasible choice; there was no river valley extending west from Baltimore that would allow for construction of a water-based transportation corridor. The solution was to use new technology and construct what became first common carrier railroad in North America. The intended endpoint was 400 miles west on the Ohio River, which was finally reached in 1852.

Choosing to invest in a railroad was a gamble. At the time, it was not clear that locomotives could haul substantial amounts of freight; rail systems in other states were using horses and mules. The first steam-powered intercity railway line in the world did not open until 1830, with the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in Great Britain and then the South Carolina Railroad at the end of the year. The B&O relied upon horses and mules until 1831, when it purchased its first steam-powered locomotive.1

When the Baltimore merchants obtained the charter, no one in the United States had demonstrated that it was even possible to build a railroad through the mountains. The investors had to speculate on the costs and time required for the project:2

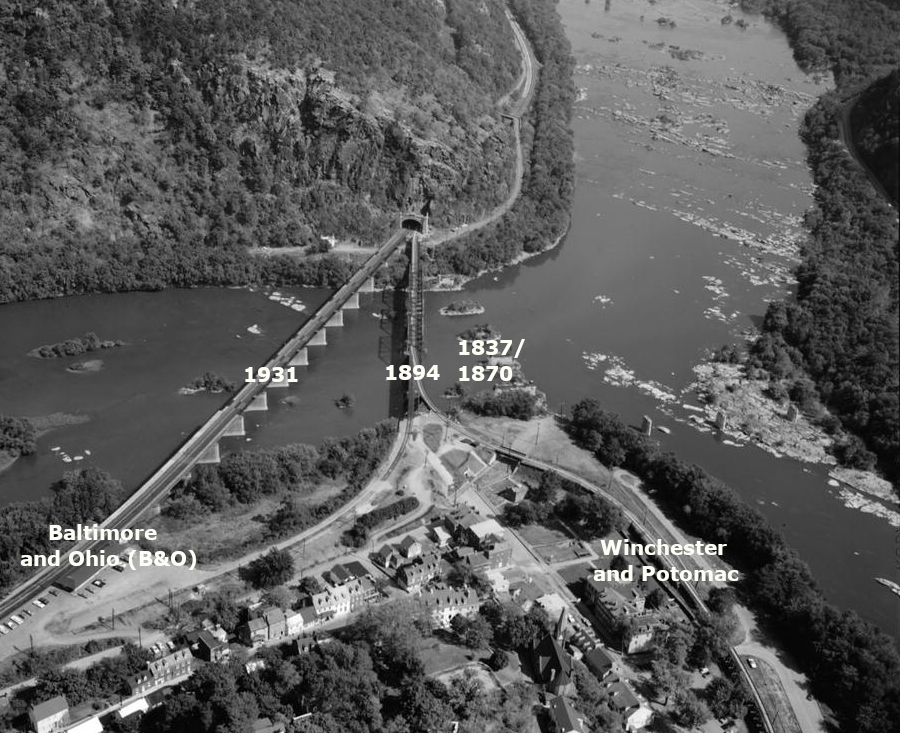

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad reached Maryland Heights, across the Potomac River from Harpers Ferry, in 1834. In 1837 it completed a bridge across the Potomac River and created a junction with the Winchester and Potomac Railroad. That railroad contributed a small percentage of the costs to build the brdge, which was designed to create a direct connection between the two lines.

Baltimore & Ohio Railroad bridge at Harpers Ferry in 1858

Source: Edward Beyer, Album of Virginia

After the original design of the bridge was adopted, the Winchester and Potomac Railroad decided that it would not allow the B&O to share its route for six miles up the Shenandoah River. That decision forced the B&O to build due west from the bridge, making a sharp turn to go through the Federal armory along the Potomac River shoreline before building up the Elks Run valley. The Potomac River route also required modifying the bridge's design, adding two piers and creating a Y-shaped intersection (a "wye") to maintain the connection to the Winchester and Potomac Railroad.

After the wooden railroad bridge was destroyed in the Civil War, an all-iron truss bridge was built in 1870. The bridge designer, Wendel Bollman, reutilized the piers of the 1837 structure.

An 1894 replacement bridge reversed the pattern of the wye; the mainline of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was made straighter on the West Virginia side after a tunnel was cut through Maryland Heights. By 1894 the Winchester and Potomac Railroad had been incorporated into the B&O as the Valley Branch, so the new bridge design decisions were based on just the pattern of traffic. The 1870 bridge was converted for use by vehicles and pedestrians.

Later, a 1931 bridge eliminated most of the B&O's curved track through Harpers Ferry. The 1894 bridge was dedicated wholly to trains on the Valley Branch going to and from Winchester, and it is still in use. The 1870 bridge was washed out in a 1936 flood, but its piers are still visible.

the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad has built multiple bridges across the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry

Source: Library of Congress, Aerial View Of The "Point" At Harpers Ferry, Looking East

The original plan to build track on the Maryland side of the river to Cumberland had been sacrificed in earlier negotiations with the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. The railroad obtained the right to build alongside the canal from Point of Rocks west 13 miles to Harpers Ferry, but at that water gap the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was obliged to cross the river to the Virginia shore. Without that agreement, the first Baltimore and Ohio Railroad track in Virginia would have been located 60 miles further west as the railroad built from Cumberland, Maryland towards the Ohio River.

Between 1839-1842, Baltimore and Ohio Railroad track was extended from Harpers Ferry westward through Virginia. The track crossed the Potomac River again into Maryland near Cumberland. Coal shipped east from Cumberland became a steady generator of revenues.3

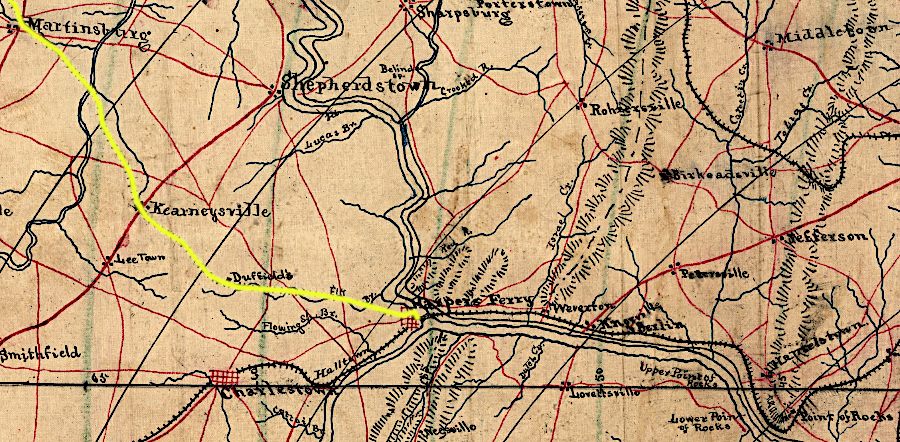

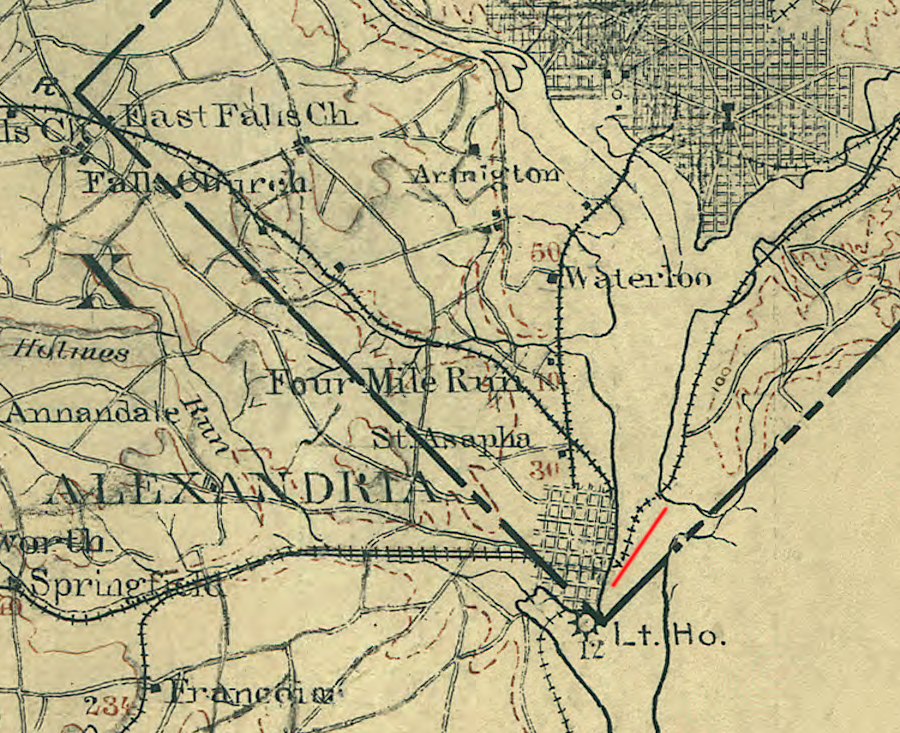

the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad built west from Harpers Ferry to Martinsburg, because the C&O Canal gained exclusive rights to the north bank of the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Map of portions of Virginia and Maryland, extending from Baltimore to Strasburg (186__)

Selecting the route to go west from Cumberland to the Ohio River was a difficult decision. Since Maryland's boundary did not include the western end of the railroad at the Ohio River, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad needed to get charters from the legislatures in Virginia and/or Pennsylvania. Charters were the essential legal authorizations for the railroad company to build track in the those states.

The 1827 Virginia charter had authorized the railroad to go as far as Parkersburg at the mouth of the Little Kanawha River, but imposed a 10-year deadline for completion. When that 10-year time expired, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had reached only to Harpers Ferry. A charter amendment was required from the Virginia General Assembly.

The specific spot to be reached on the Ohio River was not just a technical decision based on using the topography to minimize steep grades and expensive river crossings. The choice of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's Ohio River endpoint was complicated by economic and political rivalries between Pittsburgh, Wheeling, and Parkersburg.

Pittsburgh had 70,000 residents and industries beginning to take advantage of the nearby coal and iron ore. Building track to Pittsburgh would get the railroad to the Ohio River by the shortest route, and offered the potential for substantial freight traffic.

The National Road, the first interstate highway built with Federal funds as an "internal improvement," had been completed from Cumberland to Wheeling in 1818. It was clear that Wheeling would develop as a commercial center, even though there were only 11,000 residents when the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was choosing its western endpoint.

At that time there were only 1,400 people living at Parkersburg, but it was the upriver stopping point for year-round steamboat traffic on the Ohio River. Building due west from Cumberland to Parkersburg would cost less to construct than angling northwest to Wheeling, and Parkersburg offered the shortest route for extending the railroad further west to Cincinnati and St. Louis.

The legislatures in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia were lobbied heavily by the east coast port cities that feared/wanted a particular route to the Ohio River. Richmond merchants wanted to retain the trade it already received from Parkersburg via the Northwestern Turnpike, which would grow with completion of the James River and Kanawha Canal. The backers of the canal feared competition from a railroad that would haul freight and passengers to Baltimore. Philadelphia merchants were financing construction of the Main Line Canal and then its replacement railroad. They too objected to authorizing a Maryland-based railroad to send western Pennsylvania trade from Pittsburgh to Baltimore.

The Virginia charter was modified in 1838 to extend the 10-year deadline for completion, and the new charter included two key modifications. The railroad was required to build to Wheeling, and to stay within Virginia between Harpers Ferry-Cumberland (except for the last six miles). The new requirements ended consideration of an all-Maryland route via Hagerstown to Cumberland, which would have left Harpers Ferry on just a branch line with an extension via the Winchester and Potomac Railroad to Winchester.

The Pennsylvania legislature had issued a charter in 1828 for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to build from Cumberland to Pittsburgh, but required completion within 15 years. The railroad had reached Cumberland in 1842, building all but the last few miles within Virginia. If the B&O was going to build track from Cumberland northwest to Pittsburgh, it required a new charter from the Pennsylvania legislature.

The company received a new Pennsylvania charter in 1846 that permitted the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to build to Pittsburgh, but the charter included a provision that blocked the authorization if the Pennsylvania Railroad managed to raise a specific amount of capital within a year. Getting the Pennsylvania legislature to grant the 1846 charter to the B&O gave Pittsburgh two chances to become a railroad destination, and ultimately stimulated Philadelphia investors to finance completion of the Pennsylvania Railroad across the state. A B&O connection to Pittsburgh was not opened until after the Civil War.4

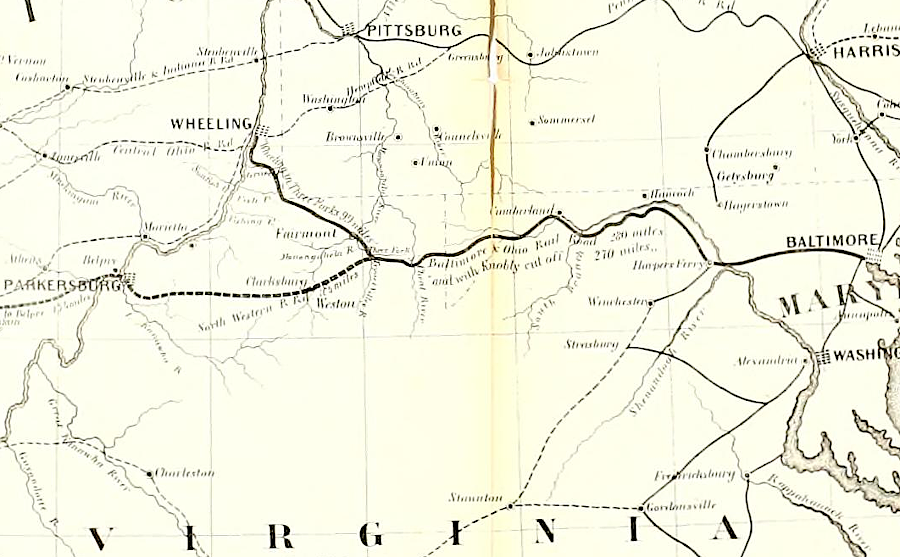

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad reached Wheeling in 1852, as required by its 1838 Virginia charter. It simultaneously planned to build to Parkersburg using the Northwestern Virginia Railroad, which was chartered by the Virginia legislature in 1851. The City of Baltimore and the railroad investors financed construction from what became Grafton to Parkersburg on the Ohio River. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad assumed operational control over the Parkersburg Branch in 1856 and started operations the next year.5

the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad built to the Ohio River at Wheeling and via the Northwestern Virginia Railroad to Parkersburg, with a junction at Grafton

Source: A history and description of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad (p.13)

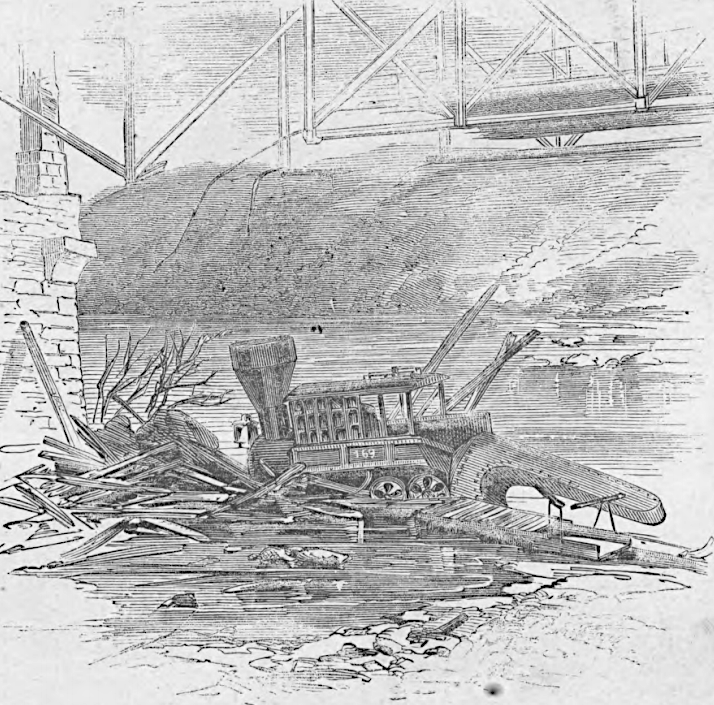

At the beginning of the Civil War, Virginia forces under command of Thomas (later "Stonewall") Jackson controlled Harpers Ferry. Before withdrawing in June 1861, those troops transported much of the Harpers Ferry Armory machinery to Richmond and burned the bridge over the Potomac River. Jackson also removed tools, telegraph wire, and other equipment from the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad shops at Martinsburg and destroyed locomotives and rail cars there. One engine was on the Winchester and Potomac Railroad tracks when the bridge was burned. A few days later, a detachment returned and drove the engine off the end of the bridge, crashing it into the Potomac River.

Confederates drove a B&O locomotives off the end of the burned bridge at Harpers Ferry

Source: Harper's Weekly, Harpers Ferry (July 20, 1861, p.455)

According to one tale, perhaps a myth manufactured by a Confederate general after the war, Jackson also captured over 40 B&O locomotives by an ingenious scheme. He had initially allowed trains loaded with coal for the US Navy to pass through Harpers Ferry, but then restricted the hours of operation to just two hours/day. That supposedly created a traffic jam with trains lined up at Martinsburg headed east and at Point of Rocks headed west. At a chosen moment, Jackson's men destroyed tracks and trestles, trapping locomotives and cars at Martinsburg.

At the end of June, under the leadership of Thomas Sharp, Confederate forces began hauling rail cars down the Valley Pike from Martinsburg to Strasburg. At the beginning of July, Jackson ordered the cars and locomotives destroyed. Harpers Ferry was too hard to defend, and the Confederate Army withdrew 40 miles south to Winchester.

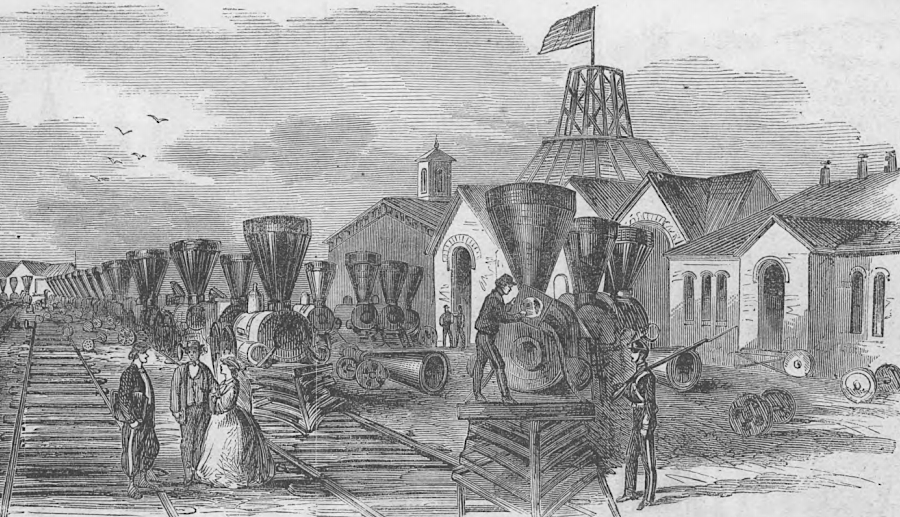

The locomotives lost at Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg were valuable to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, but it had 236 locomotives in the company's fleet. In contrast, all 15 of Virginia's railroads in 1861 had a total of just 136 locomotives, most of which were not as powerful as those on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

In August 1861, the Confederate Army returned to Martinsburg. Thomas Sharp had workers remove 14 locomotives that had been scorched but not destroyed by fire. The engines were partially disassembled to lighten their weight, then hauled along the Valley Turnpike by teams of up to 40 horses to Strasburg. Two were abandoned on the turnpike, but 12 were reassembled and taken via the Manassas Gap Railroad to Richmond for repair. At the same time, two Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire locomotives were hauled overland from that railroad in Leesburg to the Manassas Gap Railroad depot at Piedmont Station (now Delaplane).

Sharp also managed the removal of 73 miles of rails from the roadbed, enough to replace rails on 36.5 miles of track in areas controlled by the Confederates.

Moving the locomotives stopped in October, with one still sitting on the turnpike. In the Spring of 1862, that last locomotive was placed on the tracks at Strasburg, pulled to Mount Jackson, then hauled by road again all the way to Staunton. By that time, the Union Army controlled the Manassas area and there was no potential of moving the locomotive via the Manassas Gap Railroad to Richmond. The locomotive had to be hauled overland to the Virginia Central line.6

Stonewall Jackson's men destroyed B&O locomotives at Martinsburg in June 1861, then retrieved some and hauled them to Strasburg

Source: Harper's Weekly, Destruction of Locomotives at Martinsburg, VA (August 3, 1861, p.491)

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, with assistance from the Union Army, rebuilt the bridge at Harpers Ferry - and rebuilt it again, after Confederates burned it again in 1862. After being interrupted between Cumberland and Point of Rocks from May 1861-March 1862, the B&O managed to operate regularly throughout the Civil War despite multiple raids that destroyed track, trestles, and equipment. The ability of workers and managers to maintain service, as much as possible, kept it from being seized by the Federal government and turned over to the US Military Rail Road.7

After the Civil War, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad sought to acquire railroads in Virginia and extend its network deep into the southern states. The competing Pennsylvania Railroad had a similar strategy. Both sets of northern investors took advantage of the depressed stock values of Virginia railroads. They had been heavily damaged during the war, and revenues from traffic was low as the economy slowly recovered.

As part of its expansion plan, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad gained control of a route east of the Blue Ridge by combining what had originally been the Orange & Alexandria, Manassas Gap, and Lynchburg & Danville railroads into the Washington City, Virginia Midland & Great Southern Railroad. The "Virginia Midland" linked Alexandria with Danville.

However, the Pennsylvania Railroad used its control of the Baltimore and Potomac (B&P) Railroad and built a "branch line" into Washington, DC. In 1872 it blocked the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad from accessing the Washington, DC end of the Long Bridge (the railroad version, built in 1863 just downstream from the 1835 passenger bridge). The Pennsylvania Railroad also built the Alexandria and Fredericksburg Railroad south from Long Bridge, creating a connection at Quantico with the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac (RF&P) railroad.

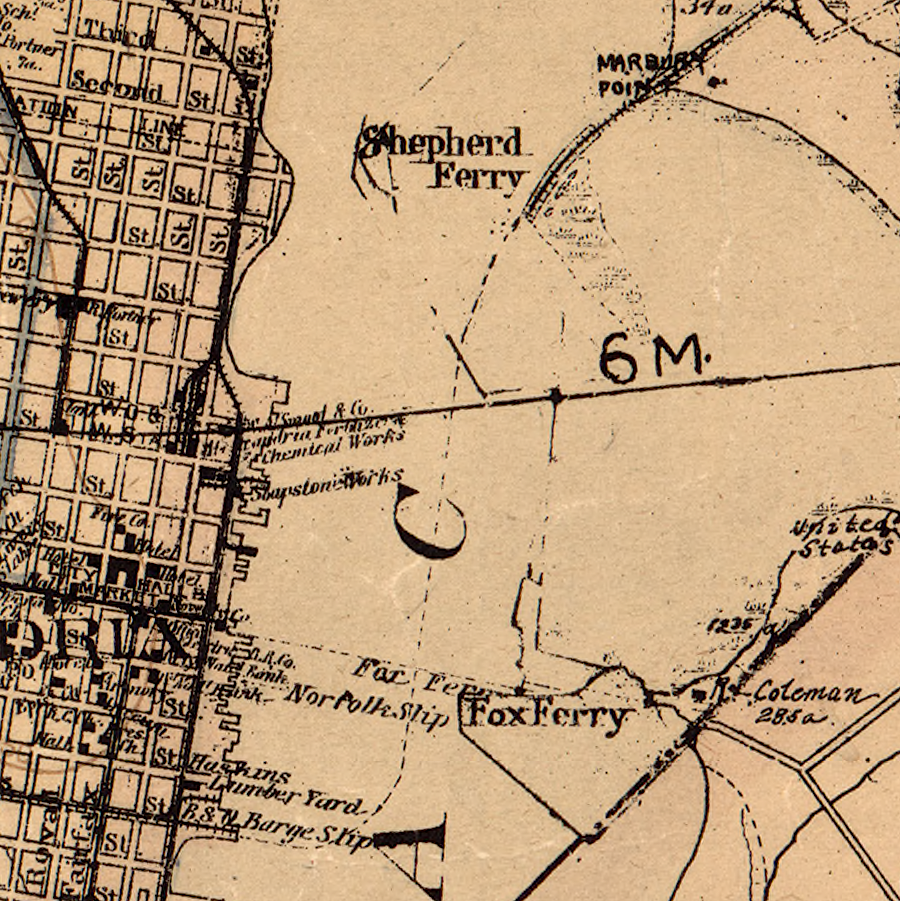

When the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad lost the ability to use Long Bridge to move freight across the Potomac River between Virginia and Maryland, the Pennsylvania Railroad had a strong competitive advantage. To regain the ability to cross the river, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad built a 12-mile branch line south from Hyattsville to Shepherd's Landing on the Maryland shoreline. Locomotives loved cars onto a car float in which tracks were installed, and it barged freight cars across the Potomac River to Alexandria. That inefficient connection was used until 1906, when all the railroads serving Alexandria opened Potomac Yard to interchange cars.

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad also planned to build its own bridge across the Potomac River upstream of Washington DC near Chain Bridge, with track in Virginia to connect to the Virginia Midland Railroad. In 1892 track was built from Silver Spring to Chevy Chase, Maryland, but then the railroad ran out of money. The Georgetown Branch has since been converted into the Capital Crescent Trail.8

West of the Blue Ridge, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad extended south of Winchester by leasing existing track between Strasburg and Harrisonburg that had been built originally by the Manassas Gap railroad. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad financed the Winchester and Strasburg Railroad, which built new track which closed the gap between those towns in 1870.

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad also financed the separate-but-allied Valley Railroad, which built track south of Harrisonburg. The goal was to connect with the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad/Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad at Salem. That would provide an alternative route to the Shenandoah Valley Railroad. That competitor was building track from Hagerstown, Maryland to Front Royal, then further south between Massanutten Mountain and the Blue Ridge.

Both the Valley Railroad and the Shenandoah Valley Railroad planned to connect with Virginia and Tennessee/Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad in the Roanoke River valley. Traffic initiated from within the valleys of the Shenandoah, James, and Roanoke rivers would not justify the expensive extensions being financed by the competing investors. However, a connection to Georgia would result in enough through traffic to Baltimore or Philadelphia to be profitable.

Both the Pennsylvania and the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) railroads retrenched their plans to extend their networks to Atlanta and other Southern cities. Borrowing capital became too expensive and profits from their investments in southern railroads were inadequate.

The Valley Railroad finally lost the race to connect with the Virginia and Tennessee/Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad. The Shenandoah Valley Railroad completed its trunk line first extending south from Hagerstown in 1882. It joined the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad at Big Lick, a location soon renamed Roanoke.

After linking up, the Shenandoah Valley Railroad and the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad merged into the Norfolk and Western Railroad. That ended the potential for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to connect the Valley Railroad at Salem. The Norfolk and Western Railroad would not be interested in interchanging north-bound traffic with a competing railroad, and would generate revenue by sending as much freight as possible east along its track trough Lynchburg to the port city of Petersburg.

Both the Pennsylvania and the Baltimore and Ohio railroads sold much of their stock in the southern railroads, and concentrated instead of extending their networks westward to the Mississippi River.

After the economic recession known as the Panic of 1893, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad went into bankruptcy. The 1896 bankruptcy ended expansion plans; instead, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began to contract. It lost control of the Washington City, Virginia Midland & Great Southern Railroad (Virginia Midland Railroad) and the lease of track south of Strasburg. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad did retain its control over the Winchester and Potomac and the Winchester and Strasburg railroads, stretching between Strasburg-Harpers Ferry.9

In 1899, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central found a way to reduce competition and ensure rates would stay high enough for railroads in the Mid-Atlantic region to be profitable. An open effort to use a Joint Traffic Association to control rates of 31 railroads operating east of Chicago had been blocked by an 1898 ruling by the US Supreme Court, which judged the association to be a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central bypassed that problem by purchasing enough shares in their competitors to gain control, then ensuring that the rates for shipping coal and other products would allow all of the lines to make a profit. Loans from New York banks financed implementation of the "Community of Interest Plan."

The Pennsylvania Railroad purchased enough shares to gain control of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. That allowed them to finally arrange more efficient shipments across the Potomac River.

The stimulus for change came from the Seaboard Air Line. In 1900, it obtained a charter from the Virginia General Assembly to build track from Richmond to Washington. Since 1872, the Pennsylvania Railroad had relied upon the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac (RF&P) Railroad to deliver traffic to one of the Pennsylvania Railroad's subsidiaries at Quantico. Virginia planned to sell its shares of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad to the Seaboard Air Line, so the Pennsylvania Railroad was threatened by a new competitor.

The solution was to create the Richmond and Washington Company in 1901. It was jointly owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, the Southern Railway, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, the Seaboard Air Line Railway, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Also in 1901 the Pennsylvania Railroad acquired control of its competitor, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, as it emerged from bankruptcy.

The Richmond and Washington Company, which was created to be a "neutral" service provider to the different owners, was given control of the tracks from Quantico to Washington, DC. It was also given the responsibility to operate the car float across the Potomac River between Shepherd's Landing-Alexandria. In 1906, car float operations ended when the different railroads serving Alexandria opened Potomac Yard and began to interchange freight there. Passengers were able to move between the six different railroads starting in 1905 after Alexandria Union Station opened. Union Station in Washington, DC opened in 1908.

For three years between November 1942-November 1945, an Emergency Bridge was constructed for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad between Alexandria and Shepherd's Landing. A bridge in Michigan was disassembled and shipped to Alexandria, then reinstalled on top of temporary wood pilings. That connection was needed to accommodate the increased traffic during World Way II. The bridge provided a backup in case German saboteurs managed to destroy Long Bridge.

Only northbound freight trains used the Emergency Bridge, with typically 6-7 trains using it each day. It was too low for ships to pass underneath, so the swing bridge was left in the open position most of the time.

after the Civil War the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad gained control of a trunk line east of the Blue Ridge, and tried to build a parallel route west of the mountains

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Seaboard Air Line and its principal connections north, south, east & west, 1896 (Rand McNally and Company)

In 1960, after the Interstate Commerce Commission allowed the Norfolk and Western Railway to purchase the Virginian Railway, it was clear that other railroads would consolidate. As trucking and pipelines captured traffic that used to move by rail, the profitability of the railroads had declined steadily. It was no longer cost-effective to maintain multiple lines of track which served the same destinations.

The New York Central proposed that it merge with the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway rejected the proposal, and instead started a bidding war to acquire the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The New York Central lost the battle. Though it did acquire over 20% and could block the C&O from filing a consolidated tax return with the B&O, it chose to sell its shares to the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in 1961.

In 1962, the Interstate Commerce Commission authorized the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad to acquire control of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The combined system could compete better against the recently-merged Norfolk and Western/Virginian railways, and respond to what one commissioner described as the "complete inability of the B&O by itself to improve its financial condition."

In 1973, the B&O, C&O, and Western Maryland Railway formed the integrated Chessie System. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad technically remained an independent corporation, and it absorbed the Western Maryland in 1983. As described in a report to the US Senate:10

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad lasted until April 30, 1987. It was folded into the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, which four months later was folded into CSX Transportation. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad lasted 160 years, the longest of any US railroad company.11

the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was forced to barge railcars across the Potomac River, from Shepherds Ferry to Alexandria waterfront, between 1872-1904

Source: Library of Congress, Baist's map of the vicinity of Washington D.C (1918)

the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad built track to Marbury Point in Maryland, to ferry cars to Alexandria

Source: Library of Congress, Map of northern Virginia (1894)

the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad controlled multiple railroads in Virginia in the 1870's

Source: Library of Congress, General map of the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road & its connections (1878)