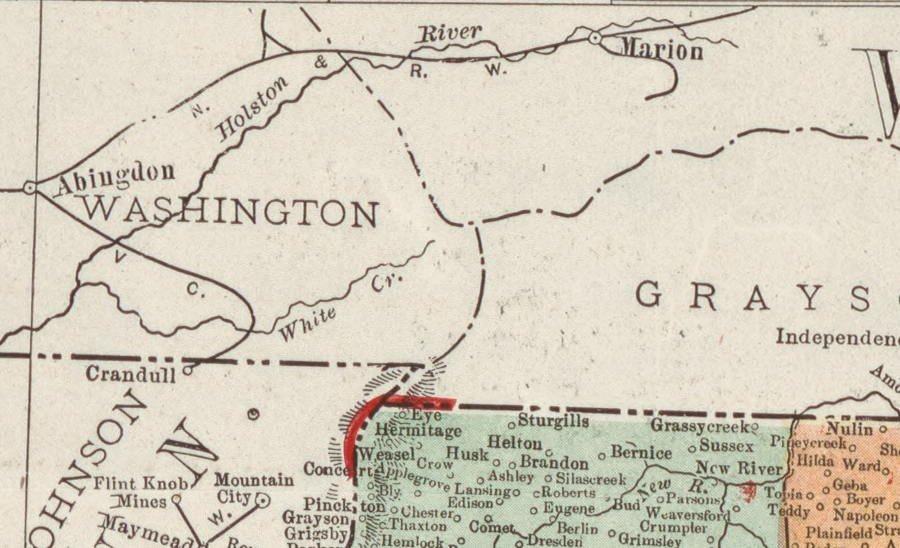

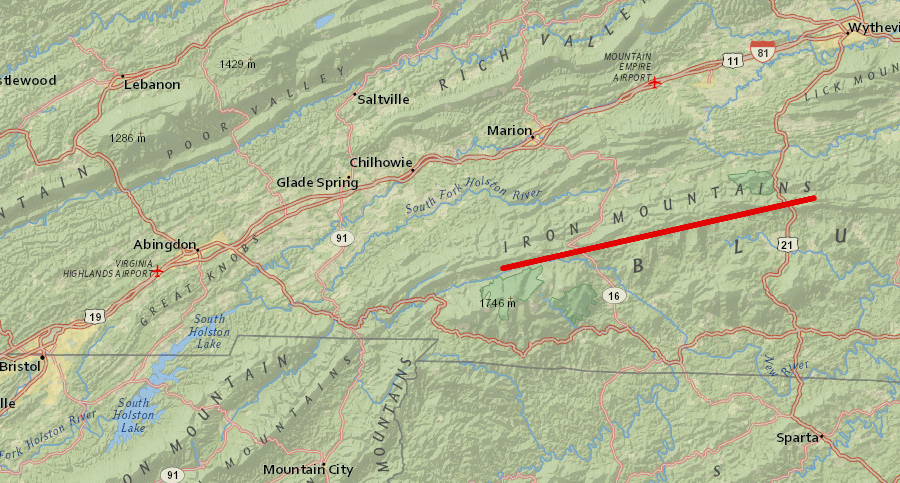

the Virginia-Carolina Railroad (red) and the Beaver Dam Railroad (yellow) moved timber products through the Blue Ridge to mills and market via Abingdon in 1911

Source: US Geological Survey, Abingdon, VA 1:125,000 scale topographic quadrangle (1911)

the Virginia-Carolina Railroad (red) and the Beaver Dam Railroad (yellow) moved timber products through the Blue Ridge to mills and market via Abingdon in 1911

Source: US Geological Survey, Abingdon, VA 1:125,000 scale topographic quadrangle (1911)

Abingdon investors tried to build a railroad east into the mountain of North Carolina, starting with the Abingdon Coal and Iron Railroad in 1885. Former Confederate General John D. Imboden speculated that the Iron Mountains had commercial quantities of iron and the region could become a steel producing center, just as he had speculated earlier that Big Stone Gap could become a boomtown.

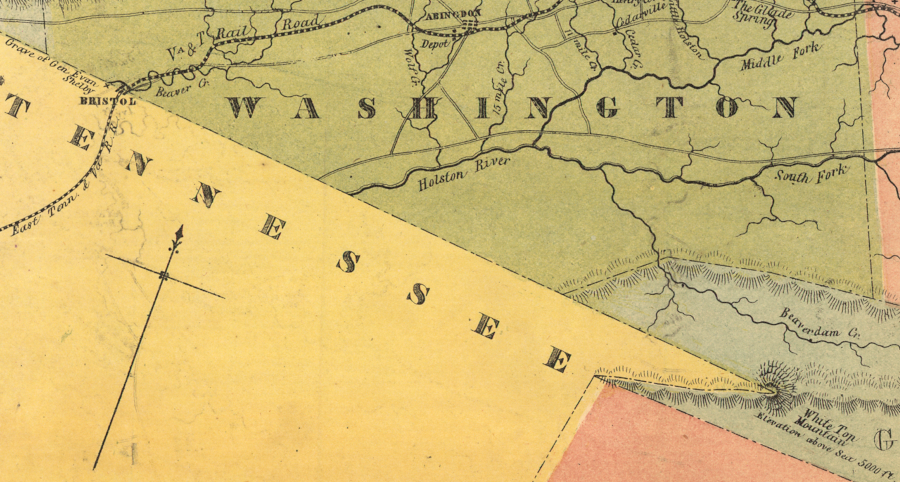

the Virginia and Tennessee brought the first railroad to Abingdon six decades before the "Virginia Creeper" was built to Whitetop Mountain

Source: Library of Congress, Map & profile of the Virginia & Tennessee Rail Road (William Willis Blackford, 1856)

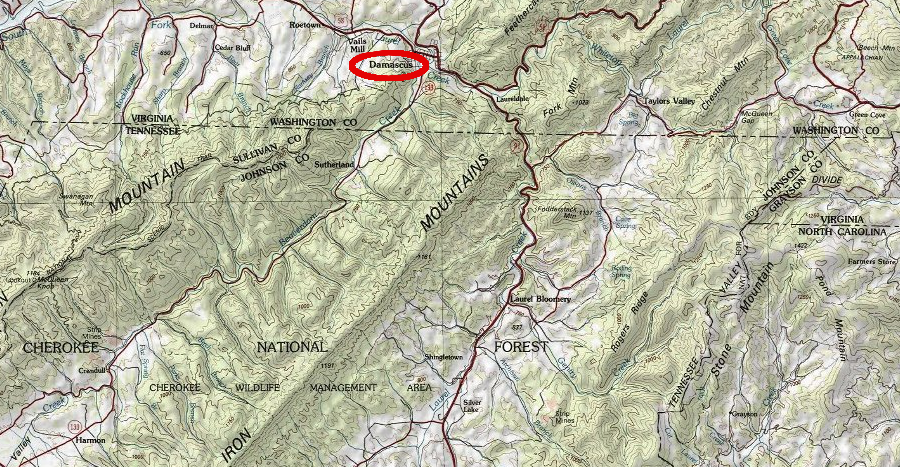

General Imboden bought land around Mock's Mill, named after early pioneer Henry Mock.

when General Imboden purchased Mock's Mill, there was no railroad connection to the Norfolk and Western Railroad

Source: US Geological Survey, Abingdon, VA 1:125,000 scale topographic quadrangle (1888)

Imboden renamed the community "Damascus" in 1886. The city of Damascus in Syria was famous for manufacturing swords with high-quality steel.1

General Imboden renamed Mock's Mill as Damascus, anticipating steel production like that in swords from Damascus, Syria

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Abingdon Coal and Iron Railroad was unable to get enough investors to finance construction. Its proposed successor, the Virginia Western Coal & Iron Railroad, also failed to get funding. It was reorganized as the Virginia-Carolina Railroad in 1900, and finally found a key investor that allowed construction to begin.

The key was getting support from the Norfolk & Western Railroad. That railroad saw potential profits in hauling timber from red spruce and white pine in the mountains. The Norfolk & Western Railroad did not own the timberland or the trees; it relied upon lumber companies and the Virginia-Carolina Railroad to generate freight traffic.

After the Norfolk & Western Railroad committed its support, the Virginia-Carolina Railroad laid track from Abingdon to Damascus. The first train arrived on February 7, 1900.2

Much freight came in the early years from Tennessee via the separate Beaver Dam Railroad. That line shipped lumber from the Empire Lumber and Mining Company mill in Crandull, Tennessee. The Beaver Dam Railroad ran north to a junction with the Virginia-Carolina Railroad at the Tennessee-Virginia state border, one mile from Damascus.

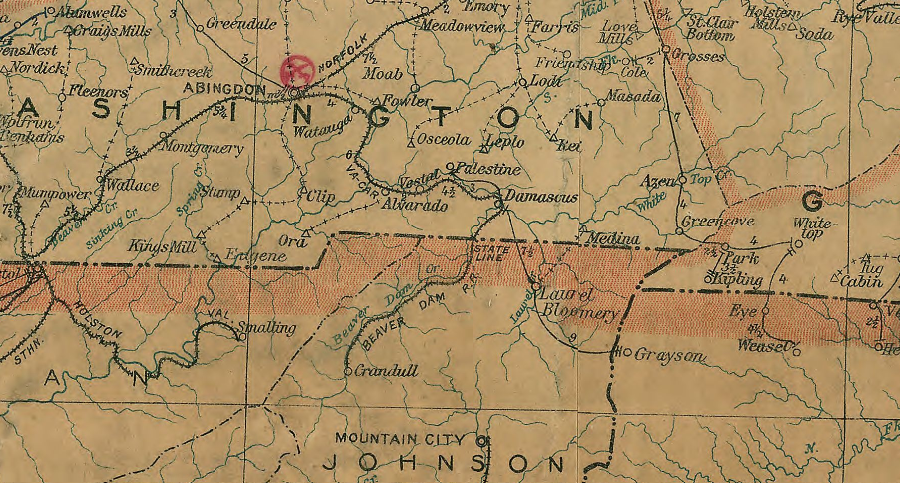

the Beaver Dam Railroad connected to the Virginia-Carolina Railroad, before construction of the extension to Whitetop and then Todd, North Carolina

Source: Library of Congress, Post route map of the states of Virginia and West Virginia (Postmaster General, 1906)

the Beaver Dam Railroad shipped Tennessee lumber to Virginia mills

Source: National Archives, System Index Map - Beaver Dam Railroad (ca. 1915–ca. 1920)

To get to the Virginia border, the Beaver Dam Railroad cut a 22-foot long tunnel through a spur of Holston Mountain in Tennessee and created the Backbone Rock Tunnel. Ripley's Believe It or Not once stated that the 48-foot long Bee Rock tunnel in Wise County, Virginia is the "world's shortest railroad tunnel" and Virginia tourism sites occasionally repeat the claim, but clearly the Backbone Rock Tunnel in Tennessee was shorter.3

the Virginia-Carolina Railroad did not go past Damascus to Whitetop in 1905

Source: Library of Congress, North Carolina (Rand McNally and Company, 1905)

The Virginia-Carolina Railroad was extended from Damascus to Whitetop in 1912. With that connection, a once-isolated place high in the Blue Ridge grew into the community of Whitetop with over 500 residents.

the Whitetop station on the Virginia-Carolina Railroad spurred growth of a community with 500 residents

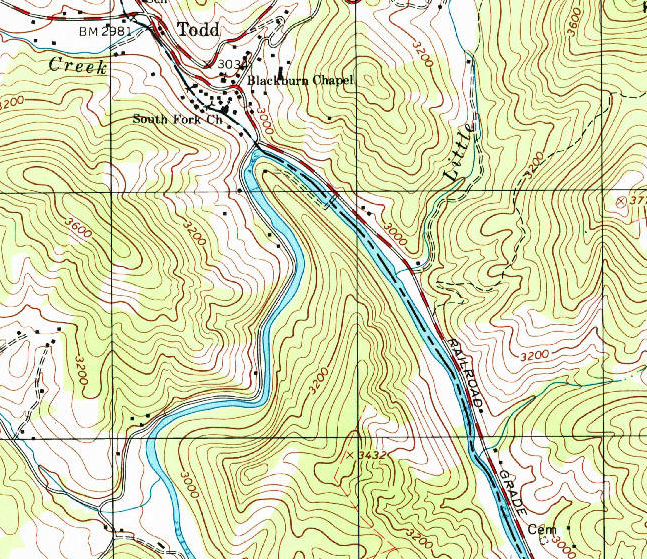

Virginia-Carolina Railroad construction ended in North Carolina at Todd, a place previously known as Elk X Roads and Elkland. The first train arrived there in 1915, and the population of that town also grew to 500. Elkland Depot at Todd was the end of the line, with a manually operated turntable to move the direction of the engines.

When the Hassenger Lumber Company built a mill at Azen (which it renamed "Konnarock"), it built a two-mile railroad to connect with the Virginia-Carolina Railroad. Its railroad, the Virginia-Carolina & Southern Railway, eventually was added to the Virginia-Carolina Railroad.

the Virginia-Carolina Railroad profited by hauling timber products, not iron, from the Iron Mountains of Virginia and North Carolina

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

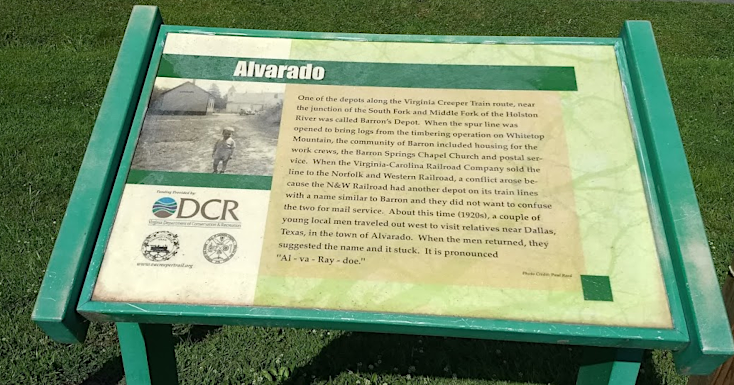

The Norfolk & Western Railroad acquired the Virginia-Carolina Railroad formally in 1919. One station on the line was renamed. There was a Barron's Depot on the Virginia-Carolina Railroad and another station with a similar name on the Norfolk and Western Railroad. Barron's Depot on the Virginia-Carolina Railroad became the Alvarado station.

Barron's Depot on the Virginia-Carolina Railroad was renamed Alvarado station after the Norfolk and Western Railroad purchased the Virginia-Carolina Railroad

Technically the railroad was the Abingdon Branch of the Norfolk & Western Railroad, but locally it was known as the Virginia Creeper. The curves, steep 7% grade, and 108 bridges required trains to move slowly over the 77 miles of track.

Diesel locomotives replaced coal-fired steam engines in 1957.4

Though the railroad did not profit from hauling iron or coal, it did transport copper ore. The Ore Knob copper mine in Ashe County, North Carolina reopened in 1953. The Virginia Creeper serviced the mine until it closed in 1962.

In 1933, the 14 miles of track between Todd and West Jefferson, North Carolina was abandoned. The timber had been cut over, the replantings by the US Forest Service would not grow to commercially-valuable size for decades, and the Great Depression limited business significantly. Operations on the line ceased completely on March 31, 1977 after a flood damaged the track and trestles.5

When the Norfolk and Western Railroad abandoned the Abingdon Branch, local governments briefly considered combining together to purchase and maintain railroad operations. The freight traffic was too thin, the difficulties of cooperating across county/state boundaries were too complex, and the challenges of obtaining reliable funding were too great.

The tracks and crossties were sold and removed in 1977. Trestle Number 6 burned slightly during removal of the crossties. They were bolted to the rails, and the cutting torch used to separate them caught the creosote-rich trestle on fire.

The right-of-way within North Carolina returned to the adjacent landowners, as was stipulated in the original purchase deeds. The option of putting the North Carolina right-of-way into a rail bank for potential re-use in the future was not pursued. If the land had been placed in a rail bank, the right-of-way would have been kept legally viable. Until needed again, a trail would have been a legitimate use of the railroad bed.

Railroad Grade Road along the South Fork of the New River near Todd, North Carolina marks the former route of the Virginia-Carolina Railroad

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Todd NC 1:24,000 scale topographic quadrangle (1998)

Within Virginia, the Virginia-Carolina Railroad had purchased the land outright for its rail line. As a result, the Norfolk and Western Railroad owned the right-of-way within Virginia as deeded land, and sold that property in three segments.

The US Forest Service acquired the right-of-way between the state line and Damascus, and added it to the surrounding Jefferson National Forest. Damascus quietly acquired the four-mile stretch between the town and its wastewater treatment plant at Drowning Ford on Laurel Creek, to ensure its rights to keep the sewage line already buried in that stretch.

distance marker on the Virginia Creeper trail

Acquisition of the remaining right-of-way between the sewage plant and Abingdon for a rails-to-trails project was more contentious. The idea of creating a trail was popular, based in part on the recent success of the Washington and Old Dominion (W&OD) rails-to-trails project in Arlington County. Trail advocates obtained a state grant to cover the purchase costs.

However, one person owning land adjacent to the railroad in Washington County convinced other landowners that the Norfolk and Western Railroad would give them the right-of-way at no cost, as had happened in North Carolina. The elected supervisors in Washington County were unwilling to support the trails project, so long as many property owners (and voters) thought there was a chance to get the right-of-way next to their land for free.

A lawsuit filed by 13 property owners delayed the trails project, but was ultimately dismissed. County supervisors finally gave the landowners several months to make their own bid to buy the railroad property. When no bid materialized, the City of Abingdon and the Town of Damascus used the state grant to purchase the western end of the right-of-way.

the Virginia Creeper trail passes through both private property and the Jefferson National Forest

A title search had revealed that the purchased right-of-way was located in just the City of Abingdon, and was not part of Washington County. Abingdon and Damascus officials had worked well together through the acquisition debates, and they agreed that the deed should transfer ownership to both communities rather than just to Abingdon.

One quirk in the trail ownership is where the railroad crossed into North Carolina, then a mile later re-crossed the state line back into Virginia briefly before entering North Carolina again. That small section in Virginia, beyond where the trail ends, is also co-owned by Abingdon and Damascus.

The town, city, and Federal agency invested in converting the railroad line into a 34-mile recreational trail. A grant from the Tennessee Valley Authority funded purchase of lumber for building new decks for walking across the trestles, and Job Corps camps provided labor.

Some adjacent property owners persisted in their opposition, blocking the Virginia Creeper Trail with logs, hay bales and gates. One rancher even put bulls on his property next to the unfenced right-of-way and placed a "Big bull in this field. Cross at own risk!" sign on the trail.

Arsonists torched Trestle No. 6 completely in 1983.

Back in 1977, all the trestles had been sold and were scheduled for removal. Advocates for converting the Abingdon Branch into a recreational trail negotiated with the cooperation of the Norfolk and Western Railroad, to acquire those trestles from the Chicago Salvage Company, which had purchased them for their scrap value.

The arson-destroyed Trestle No. 6 was replaced at great expense. Another trestle from a different abandoned railroad near Yadkinville, North Carolina was disassembled there, transported to the Virginia Creeper Trail, and reassembled. A tornado destroyed Trestle No. 7 on April 28, 2011. It was rebuilt in 2013-14.

A key advocate who nurtured the project described his occasional frustrations with the slow pace of completing the project:6

trestle #38 on the Virginia Creeper trail

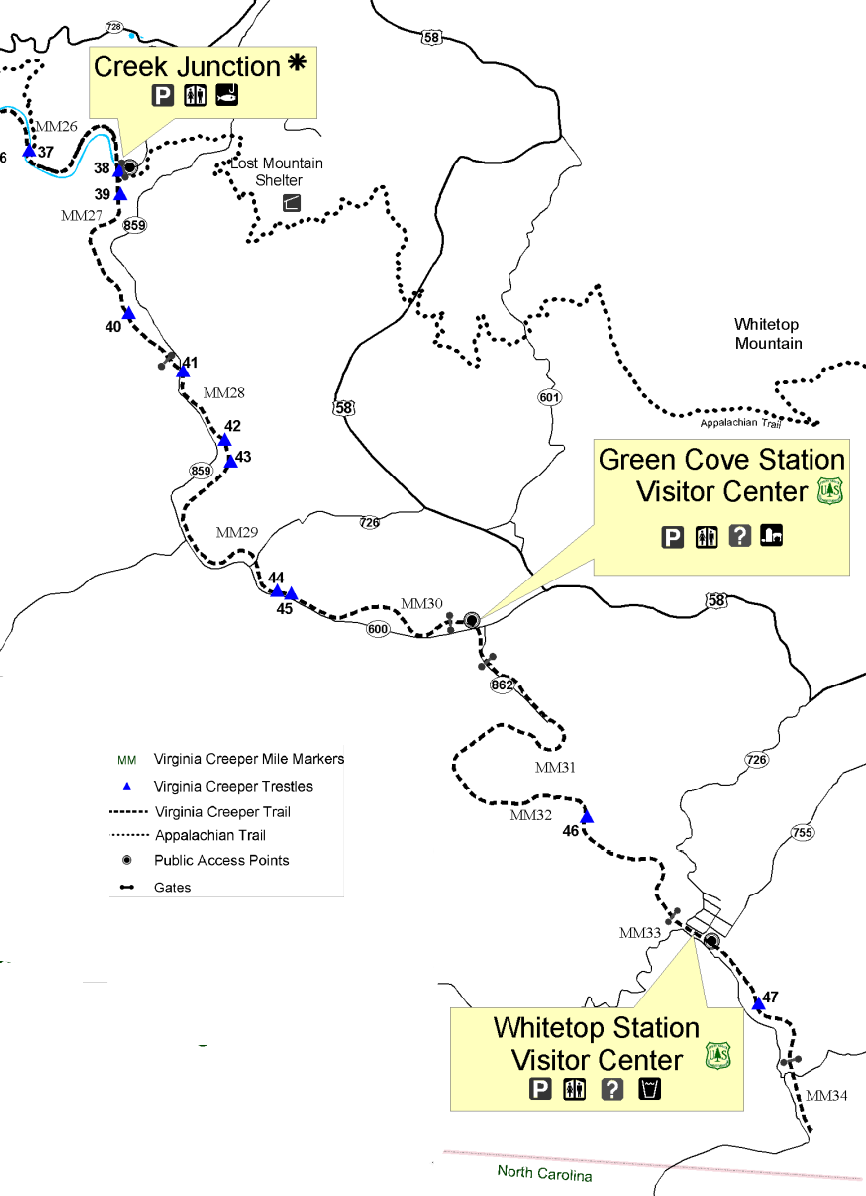

The portion owned by the US Forest Service is within the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area. The visitor center at Whitetop Station is a replica of the original train station, and the Green Cove visitor center is in the original train station building.

the Green Cove station is the only original train station remaining on the Virginia Creeper trail

The trail has a surface of limestone and cinders from the steam engine days, and local bike shops cater to customers who shuttle to Whitetop and enjoy a 16-mile downhill ride to Damascus. Hikers and horseback riders also take advantage of the shared-use trail.

the Virginia Creeper trail parallels Whitetop Laurel Creek downstream of Taylor's Valley

The trail opened in segments as it was built, and it was not fully completed until 1987. Visitation grew from 25,000 per year in 1997 to 200,000 people per year two decades later. The success of the Virginia Creeper Trail was recognized by the Rails-To-Trails Conservancy in 2014, when it inducted the trail as the 27th member of its Hall of Fame.

The tourism business is a large part of the local economy in Washington County, Virginia. Damascus is a famous "trail town" on the Appalachian Trail. The trail is on Main Street, marked by a brick sidewalk. The town hosts an Appalachian Trail Days Festival in the springtime and always welcomes hikers. Businesses in Damascus depend upon hikers and other tourists to purchase supplies, meals, and hotel rooms.

bike rental operations in Abingdon and Damascus offer shuttle rides to the top of the Virginia Creeper trail at Whitetop

Abingdon is home to the William King Museum of Art and to the Barter Theater, the "state theater" of Virginia. Those interested in a high-end hotel can stay at the Martha Washington Inn & Spa. The original living room of the 1832 house at the core of the building is now the lobby of the hotel. Abingdon has placed the last steam engine used on the Virginia-Carolina Railroad at the trailhead east of town, while Damascus has a caboose.

The Virginia Creeper Trail Club is the local non-government organization that organizes clean-ups and does maintenance projects, helping to repair the 47 trestles on the trail. Planning and conflict resolution among the primary stakeholders is handled via Trail Advisory Board. It has members from Abingdon, Damascus, the US Forest Service, the Virginia Creeper Trail Club, and adjacent private property owners for the 16 miles of trail not within the boundaries of the Jefferson National Forest.7

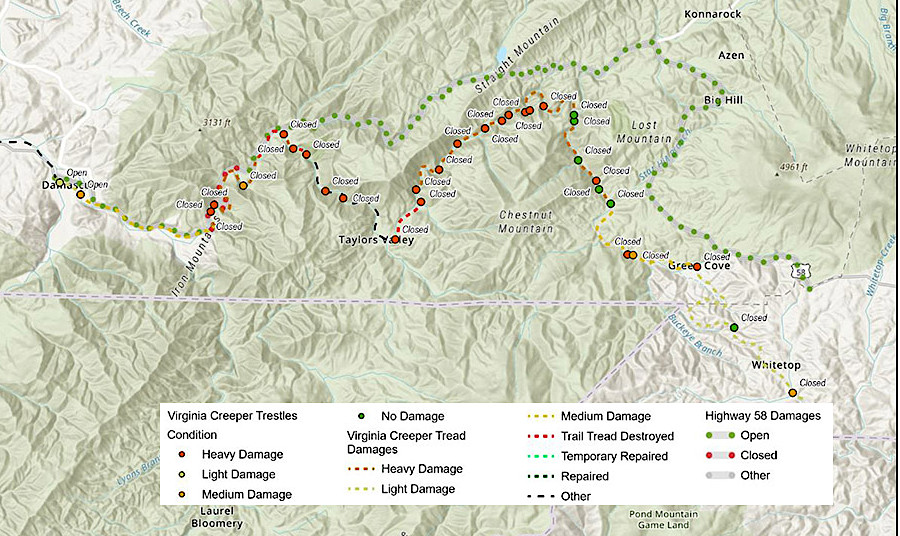

Source: Abingdon Convention and Visitors Bureau

On September 27, 2024, remnants of Hurricane Helene triggered major flooding in the Blue Ridge of western North Carolina and Southwest Virginia. Floodwaters in Whitetop Laurel Creek damaged most of the 32 trestles on the Virginia Creeper trail between Whitetop Mountain and Damascus, and 18 were destroyed. Sections of the trail were completely washed away; there was massive damage from Damascus to Whitetop Mountain.

Source: Beautiful Virginia, How long is it really going to take to fix the Creeper Trail??

Whitetop Laurel Creek washed out Trestles 19, 34, and 35

Source: Virginia State Trails Advisory Committee Meeting, Virginia Creeper Trail - Status Update (November 14, 2024)

The western half of the trail, between Damascus and Abingdon, was reopened quickly. Rangers at the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area estimated that portions of the trail would be closed until mid-2025. Three weeks after the damaging storm, the executive director of the Virginia Creeper Trail Conservancy was optimistic that Damascus would remain Trail Town USA and the trail would be rebuilt:8

The stretch of trail between Abingdon-Damascus quickly reopened. US Congress passed a disaster relief bill in December, 2024. It included $600 million to restore the Virginia Creeper Trail from Damascus to Whitetop Mountain, primarily on lands administered by the US Forest Service. Trail restoration was seen as key to economic recovery in the area, which required bringing back tourists.9

Cost estimates to repair the trail were $200-300 million, a significant portion of the $600 million estimated for watershed and forest restoration for all of the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests. In November 2025, the US Forest Service awarded a contract for $240 million to rebuild the upper 17 miles of the trail connecting Whitetop Station to Damascus. That averaged out to be $14 million per mile.10

flooding from Hurricane Helene in 2024 washed trestle 18 onto trestle 19

Source: US Forest Service, Hurricane Helene Information - Virginia Creeper Trail

flooding triggered by heavy rainfall caused Whitetop Laurel Creek to erode sections of the roadbed of the Virginia Creeper Trail

Source: US Forest Service, Hurricane Helene Information - Virginia Creeper Trail

the Green Cove station has items on the shelves that were sold in the early days of the Virginia-Carolina Railroad

an exhibit at the Green Cove station shows how store charges were documented in a McCaskey Receipt Register in the days before credit cards

the Virginia Creeper Trail, unlike the Virginia-Carolina Railroad, does not extend into North Carolina

Source: US Forest Service, Virginia Creeper Trail Map