Railroad Junctions in Virginia

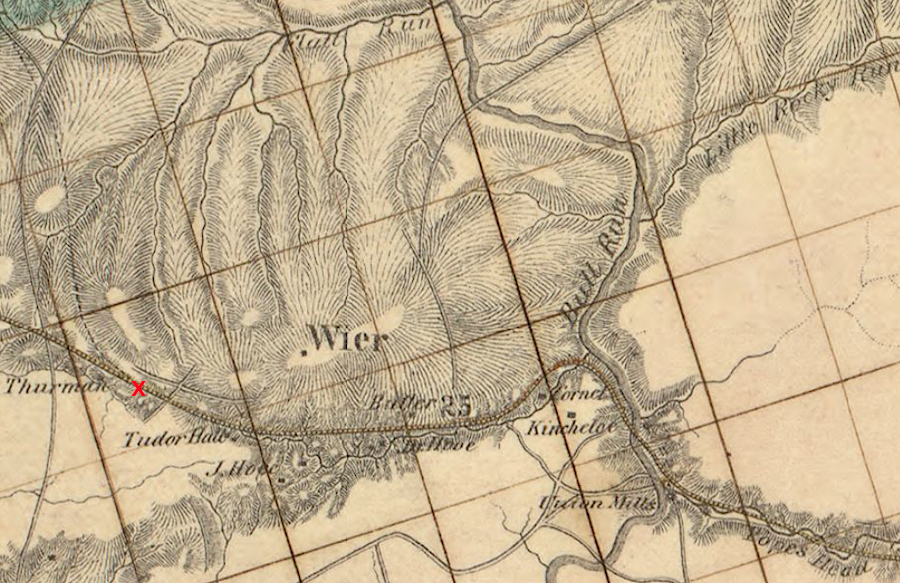

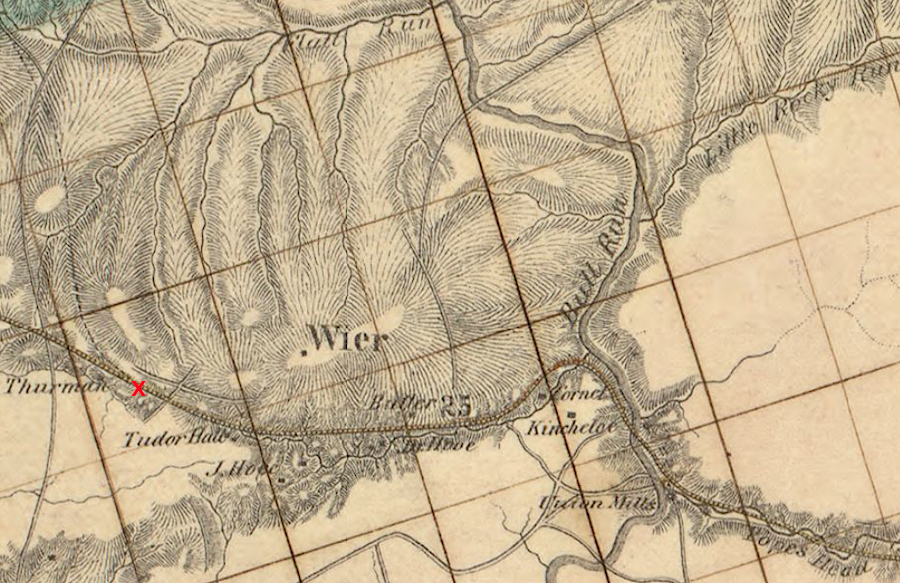

before two railroads created a junction in Prince William County, there was no reason for what became Manassas to develop there

Source: Library of Congress, Map and profile of the Orange and Alexandria Rail Road with its Warrenton Branch and a portion of the Manasses [sic] Gap Rail Road, to show its point of connection

Prior to the Civil War, railroads in Virginia were developed by Tidewater cities to steer traffic to competing ports on the Fall Line. Even though 40-60% of funding for initial railroad construction was provided by the General Assembly, the state's politicians represented sectional interests.

The pattern of railroad construction in the Shenandoah Valley before the 1860's shows most clearly that Virginia's port cities did not build a transportation infrastructure for the overall benefit of the state.

The tiny, undercapitalized Winchester and Potomac Railroad connected Winchester and the "lower" Shenandoah Valley to Harpers Ferry and ultimately (via the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad) to the port at Baltimore. There was a totally separate section of the Manassas Gap Railroad further south, connecting Mount Jackson and the middle of the Shenandoah Valley with Front Royal and ultimately Alexandria. Even further south, "up" the Shenandoah Valley, there was a separate section of the Virginia Central Railroad connecting Covington to Waynesboro and ultimately Richmond.

No railroad track connected Covington to Mount Jackson. No railroad track connected Mount Jackson to Winchester. The path of the Great Wagon Road, with a flat topographical route from the Shenandoah Valley to the Potomac River, was ignored in favor of building expensive track through the Blue Ridge.

The gaps between the three railroads in the Shenandoah Valley were intentional. After 25 years of intensive railroad construction in Virginia, in 1861 no track ran the length of the Shenandoah Valley. The Richmond-focused stockholders of the Virginia Central Railroad and the Alexandria-focused stockholders of the Manassas Gap Railroad did not want any of their business diverted to Baltimore via the Winchester and Potomac Railroad/Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

A charter authorizing construction of the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was delayed by members of the General Assembly representing Richmond and Petersburg. Leaders in those Fall Line cities did not want to see rail cars loaded with cargo bypass their ports, reducing local business and enhancing development in Hampton Roads.

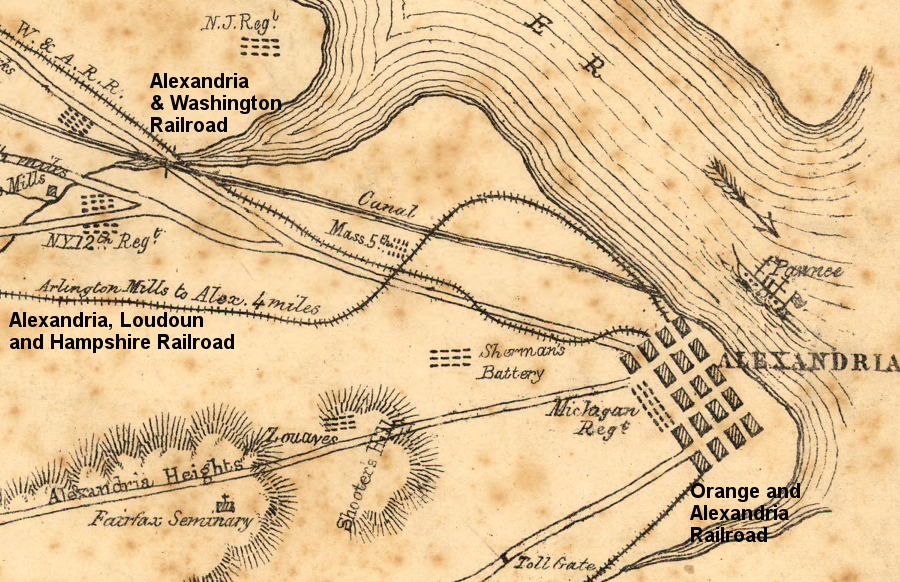

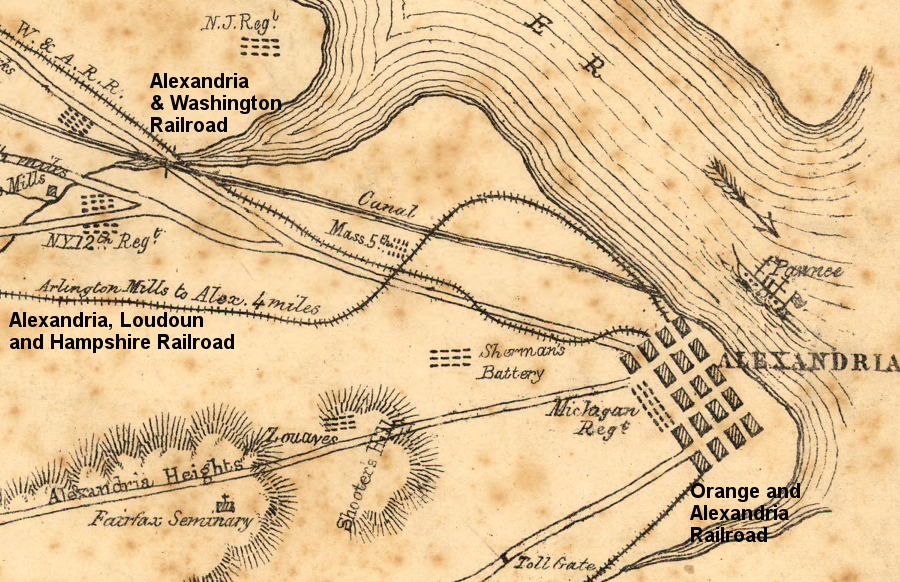

In 1861, competing railroads serviced the same communities at:

- Alexandria (Orange and Alexandria Railroad; Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad; Alexandria & Washington Railroad)

- Manassas (Orange and Alexandria Railroad; Manassas Gap Railroad)

- Harper's Ferry (Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; Winchester and Potomac Railroad)

- Gordonsville (Orange and Alexandria Railroad; Virginia Central Railroad)

- Charlottesville (Orange and Alexandria Railroad; Virginia Central Railroad)

- Hanover Junction, now Doswell (Virginia Central Railroad; Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad)

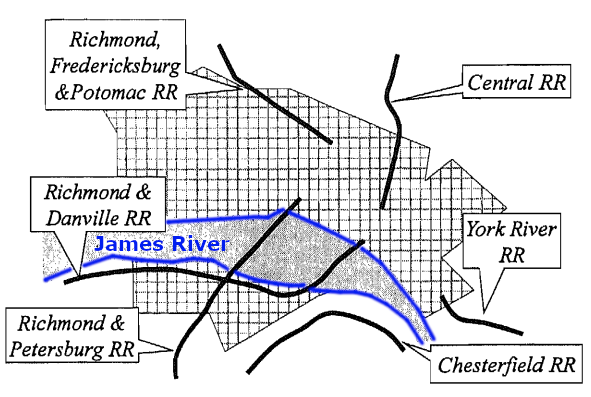

- Richmond (Virginia Central Railroad; Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad; Richmond and Petersburg Railroad; Richmond and Danville Railroad; Richmond and York River Railroad)

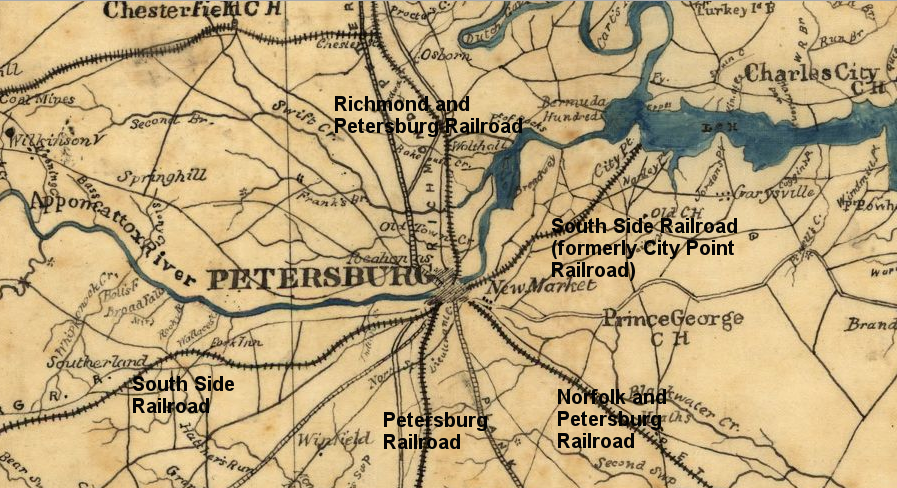

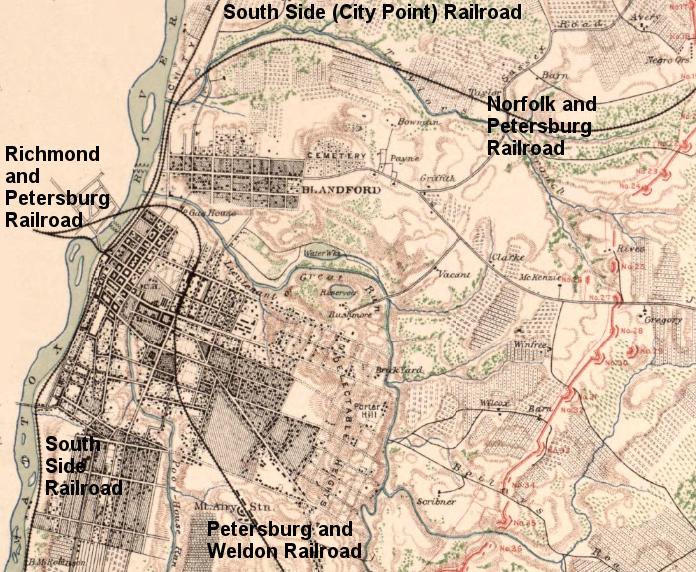

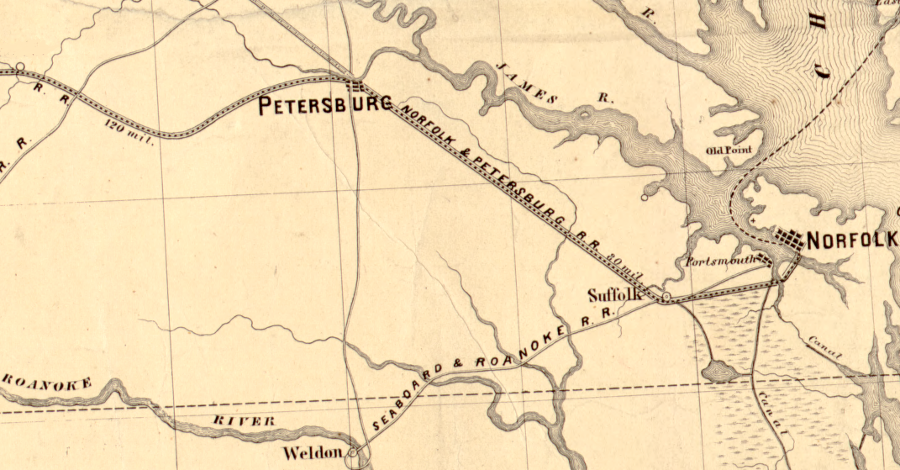

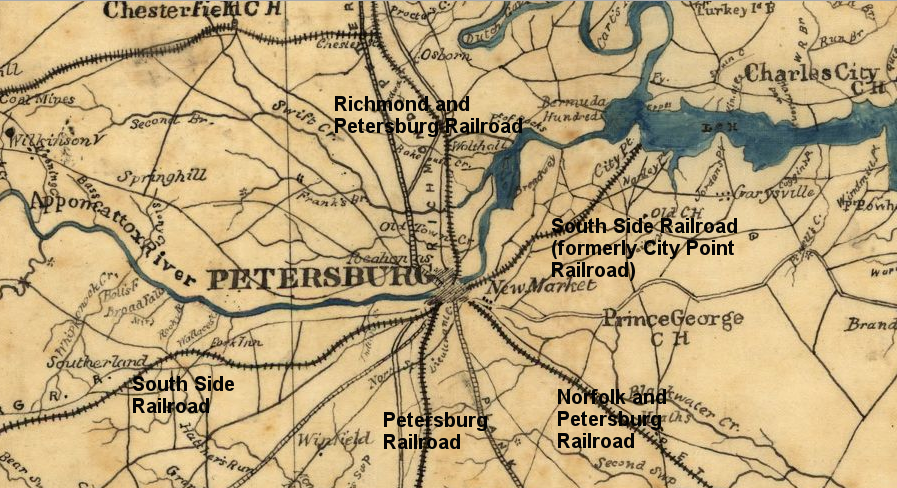

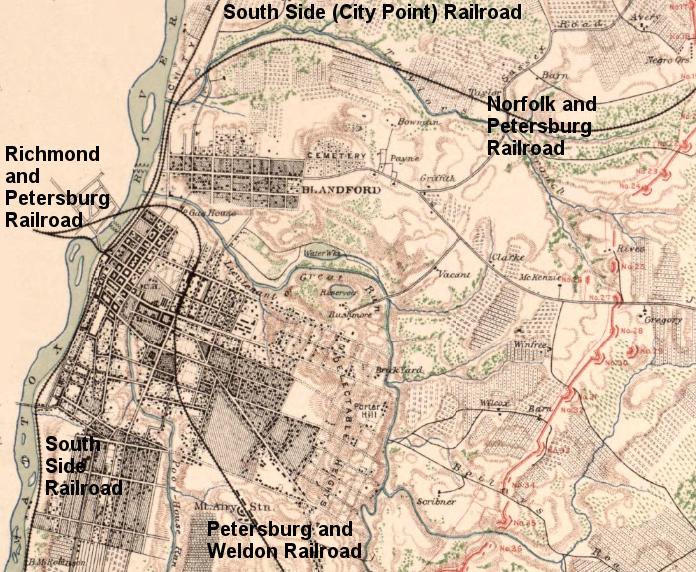

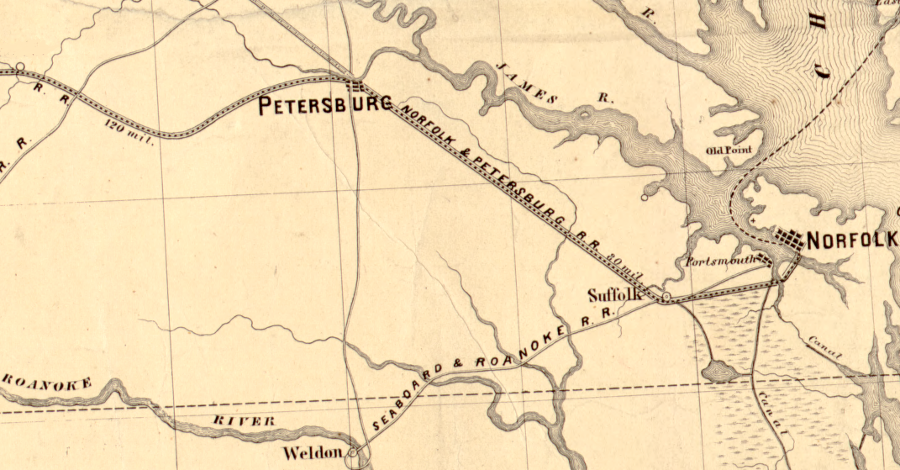

- Petersburg (Richmond and Petersburg Railroad; Petersburg & Weldon Railroad; South Side Railroad; Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad)

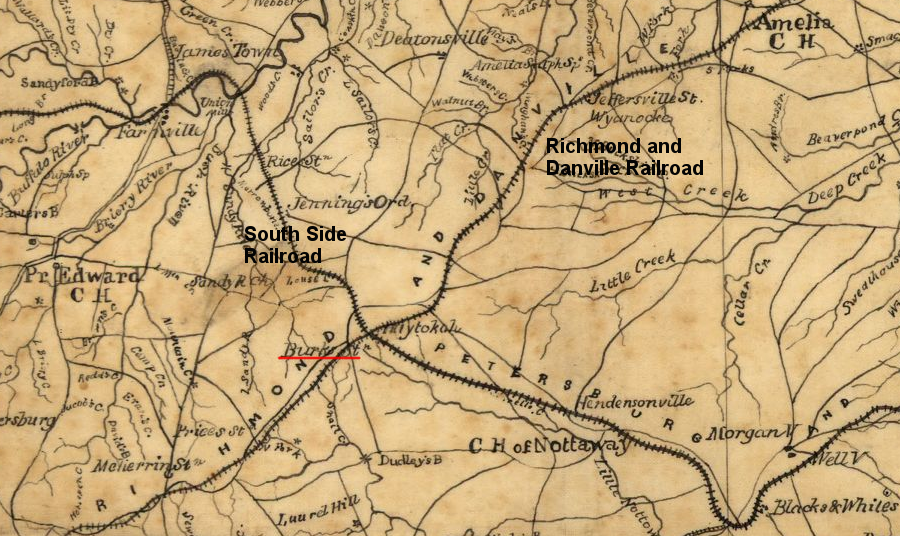

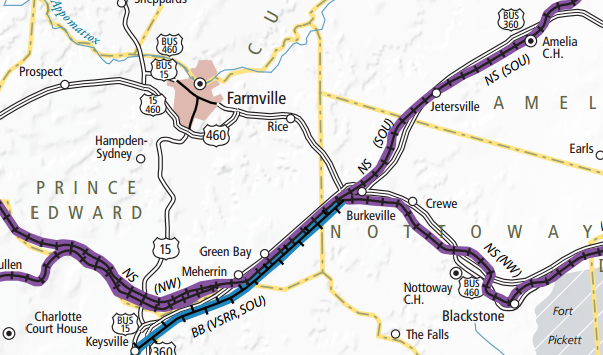

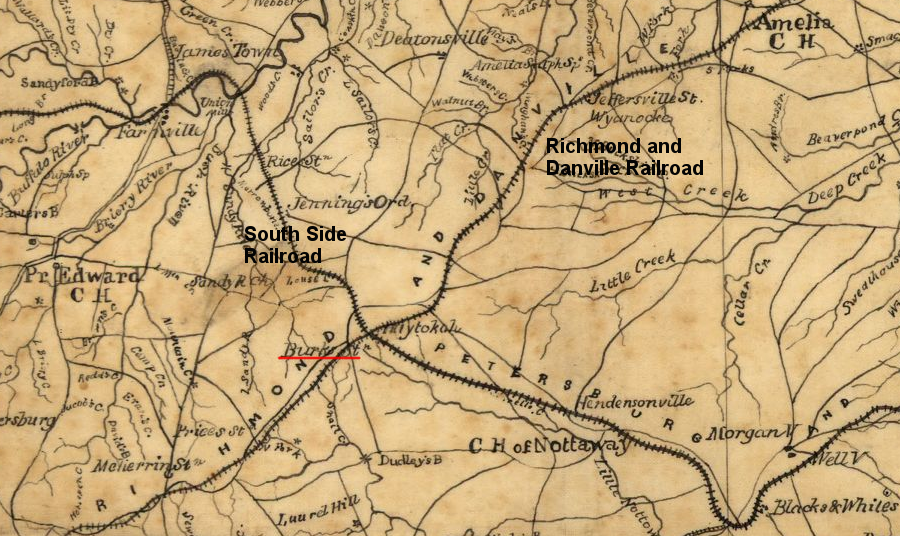

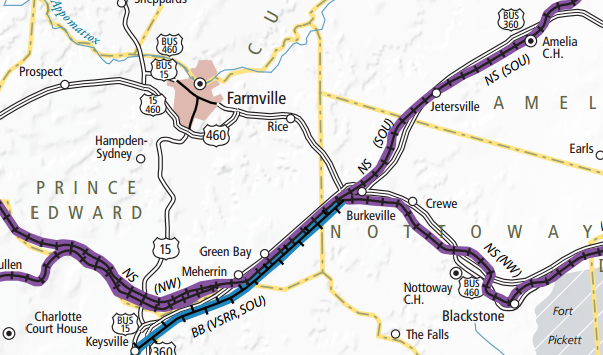

- Burke's Station, now Burkeville (South Side Railroad; Richmond and Danville Railroad)

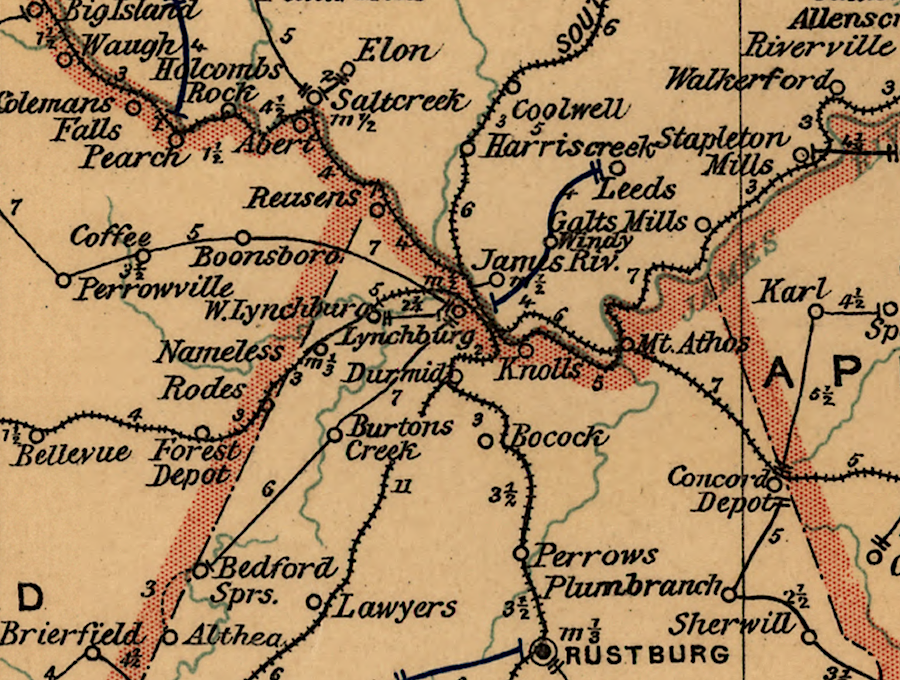

- Lynchburg (South Side Railroad; Orange and Alexandria Railroad)

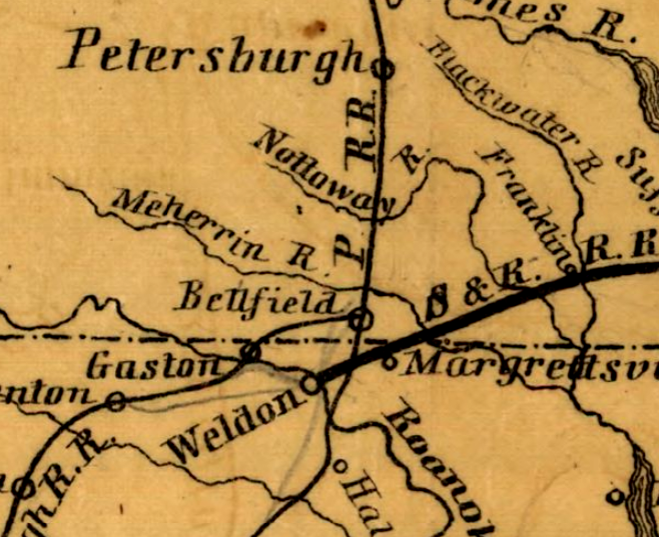

- Belfield, now Emporia (Petersburg & Weldon Railroad; Raleigh and Gaston Railroad)

- Suffolk (Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad; Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad)

during the Civil War, both the Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad and the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad ran through downtown Suffolk

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the siege of Suffolk, Va., 1863

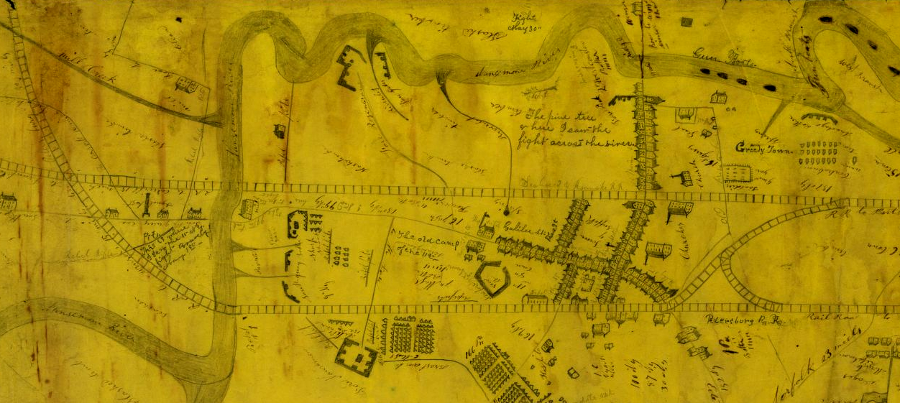

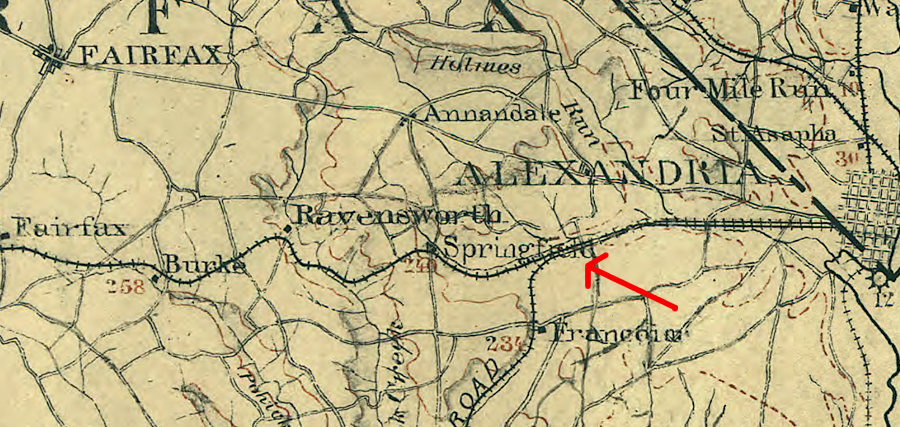

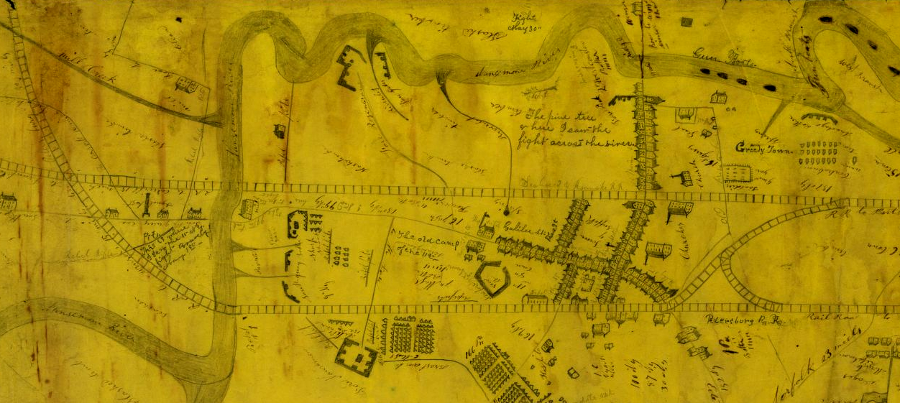

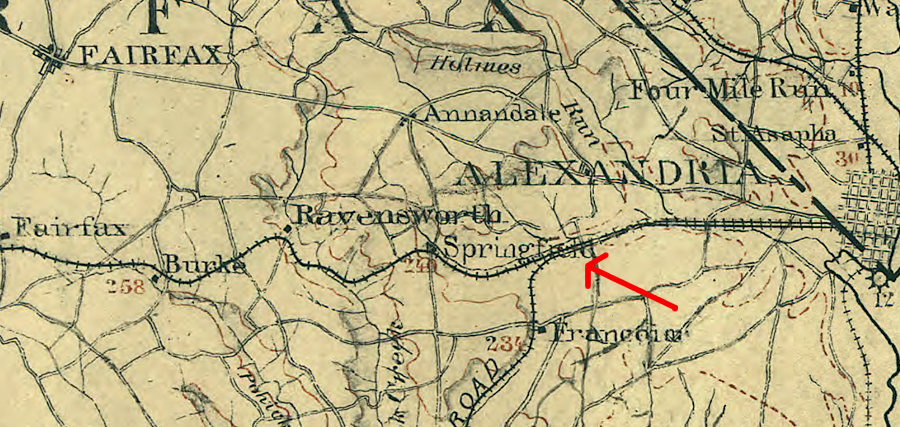

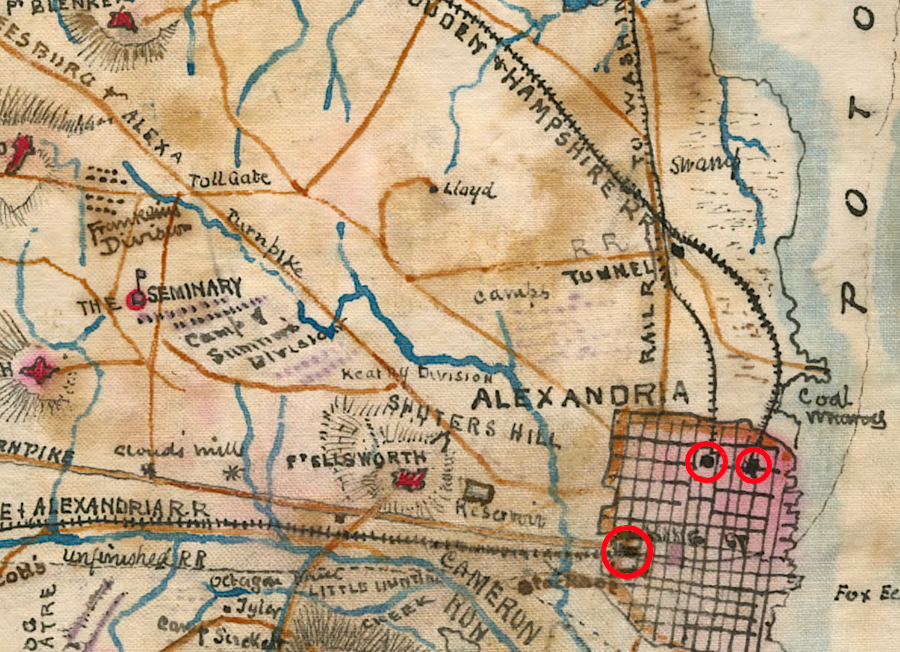

the Union Army seized Alexandria at the start of the Civil War in 1861 and finally connected the Orange and Alexandria Railroad; the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad; and the Alexandria & Washington Railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Sketch of the seat of war in Alexandria & Fairfax Cos (by V. P. Corbett, 1861)

two railroads chose to create a junction in the Piedmont of Virginia, and then the town of Manassas developed at that site

Source: Library of Congress, Colton's Virginia

the Virginia Central Railroad intersected with the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad at Hanover Junction, and with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad at both Gordonsville and Charlottesville

Source: Library of Congress, Colton's Virginia

the Orange and Alexandria Railroad and the Virginia Central Railroad at Gordonsville

Source: Library of Congress, Map and profile of the Orange and Alexandria Rail Road with its Warrenton Branch and a portion of the Manasses [sic] Gap Rail Road, to show its point of connection

Petersburg was a railroad center that provided supplies to maintain Richmond during the Civil War until the Union Army finally cut off the South Side Railroad, at which point Confederate officials abandoned their capital in April 1865

Source: Library of Congress, South central Virginia showing lines of transportation

prior to the Civil War, the South Side Railroad crossed the Richmond and Danville Railroad at Burke Station

Source: Library of Congress, South central Virginia showing lines of transportation

the rail line west of Burkeville to Farmville has been abandoned, but Burkeville is still a railroad junction with an interchange between the Norfolk Southern and Buckingham Branch railroads

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Virginia Rail Map

tracks of the competing railroads in Petersburg were linked after the Civil War started

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of the War of the Rebellion, Map of the Approaches to Petersburg and Their Defenses, 1863 (Plate XL)

the Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad brought Roanoke River traffic to Portsmouth, the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad brought Appomattox River and James River traffic to Norfolk, and the two lines crossed at Suffolk

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing route of Norfolk & Petersburg Rail Road and its connections with Ohio & Mississippi Rivers

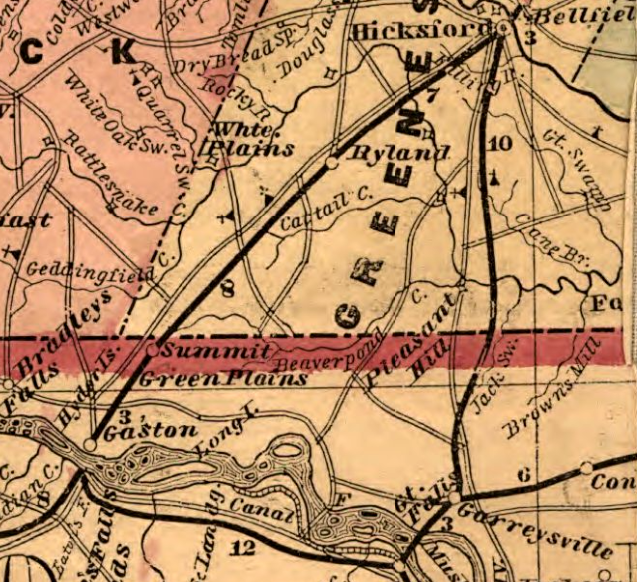

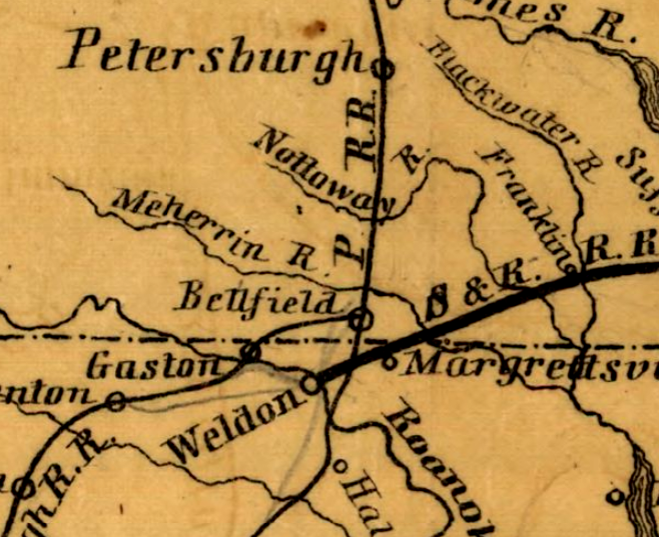

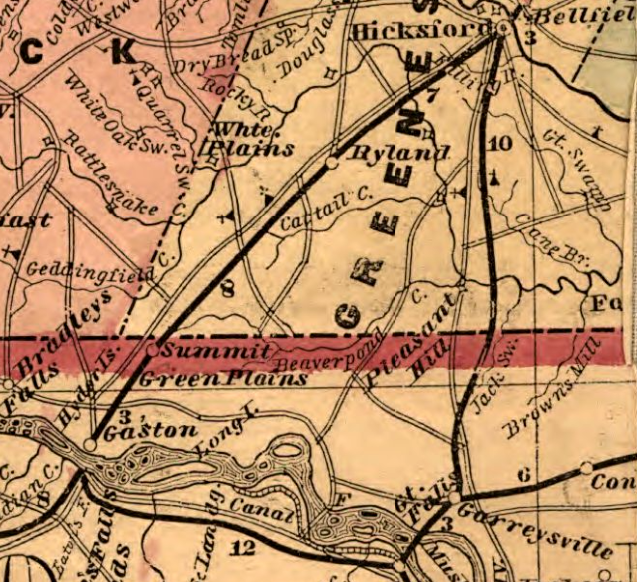

Petersburg built separate rail connections from Belfield south to Gaston and to Weldon, competing with the Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad for traffic floating down the Roanoke River

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Seaboard & Roanoke Railroad from Portsmouth, Va. to Weldon, N.C. showing its connection with railroad & steamboat routes

at the Meherrin River, where the towns of Hicksford and Belfield were later united into Emporia, separate railroad lines went south to the Roanoke River at Gaston and Weldon

Source: Library of Congress, Lloyd's official map of the state of Virginia from actual surveys by order of the Executive 1828 & 1859

When competing railroads crossed, locomotives and rail cars normally stayed on just one line. Even if the rail lines used the same gauge, cargo intended for a destination on the other railroad line was transferred to warehouses and then re-loaded on the rail cars of the other line. Passengers got off at a station and waited for a train from the other line.

There were two major exceptions. The Manassas Gap Railroad built its own track from the Shenandoah Valley through the Blue Ridge (at Manassas Gap and Thoroughfare Gap) to Manassas Junction, but never completed its "independent line" all the way to Alexandria. The Panic of 1857 limited the ability to borrow funds for continued construction beyond Manassas Junction, so the Manassas Gap Railroad paid the Orange and Alexandria Railroad to permit its trains to travel from the junction near Bull Run to the city of Alexandria on the Potomac River.

The Orange and Alexandria Railroad paid the Virginia Central Railroad to use its track from Gordonsville to Charlottesville. Before the Civil War, the Orange and Alexandria Railroad ran trains back and forth between Alexandria and Lynchburg, but the General Assembly did not authorize that company to build track between Gordonsville and Charlottesville. Instead, the Orange and Alexandria Railroad paid the Virginia Central Railroad for the right to operate trains on that stretch, until after the war a separate line was completed.1

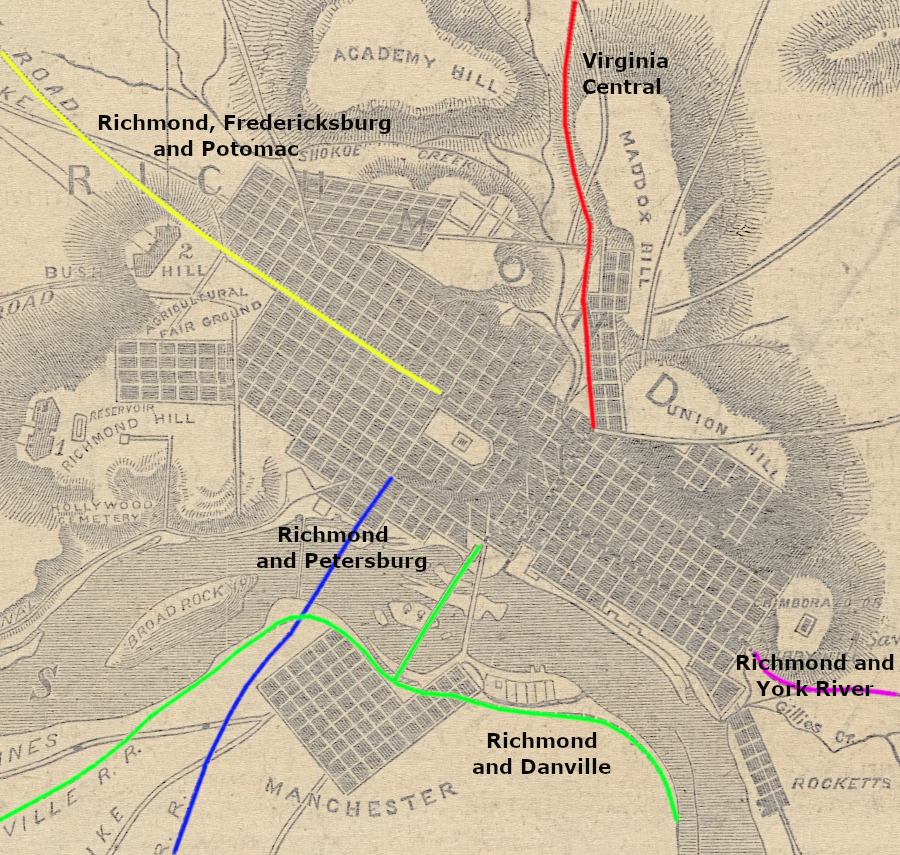

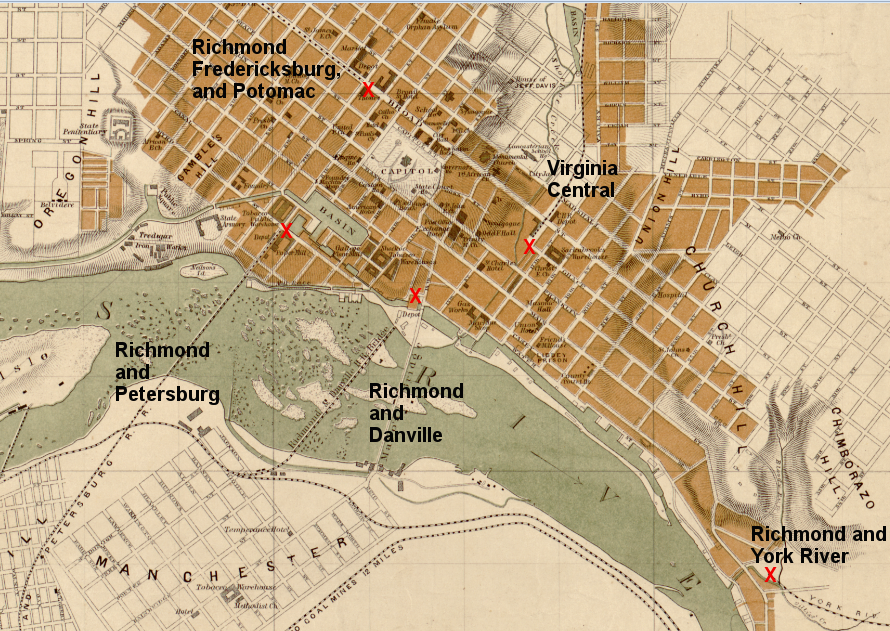

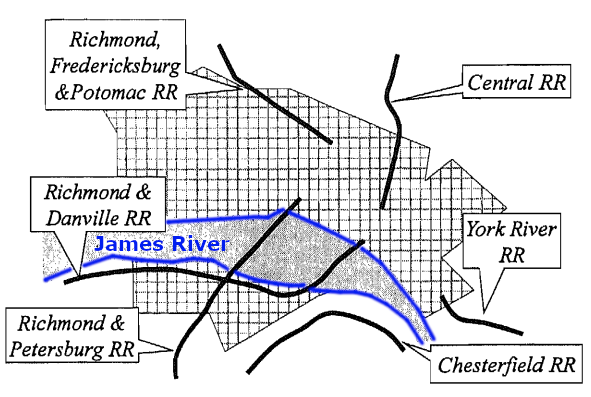

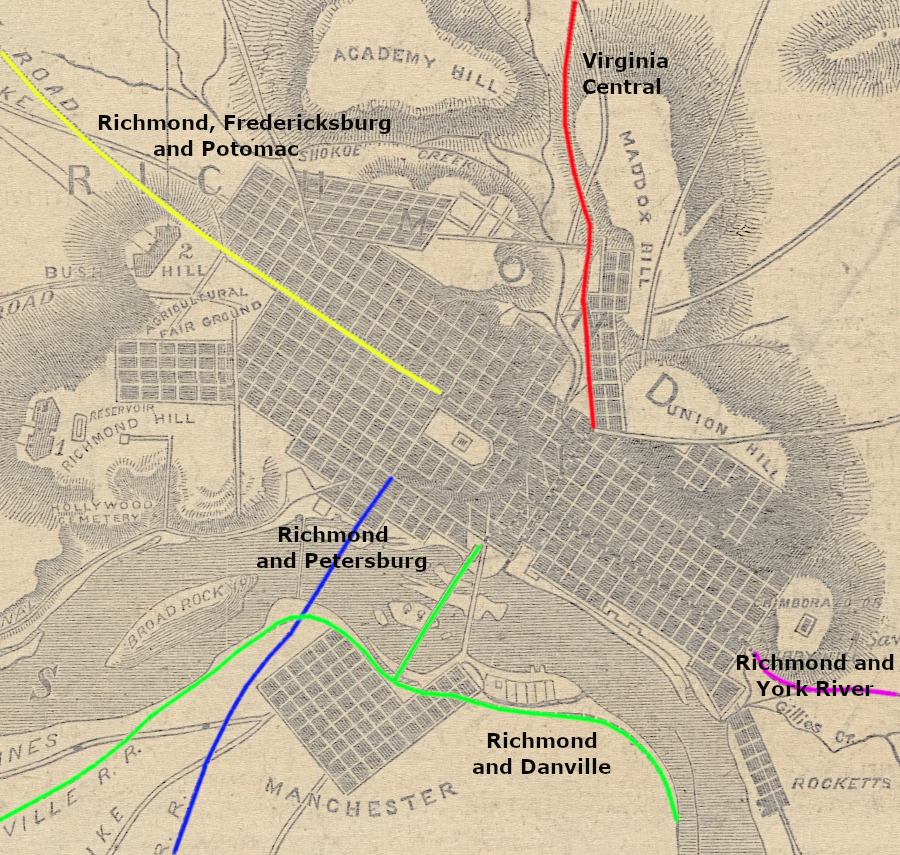

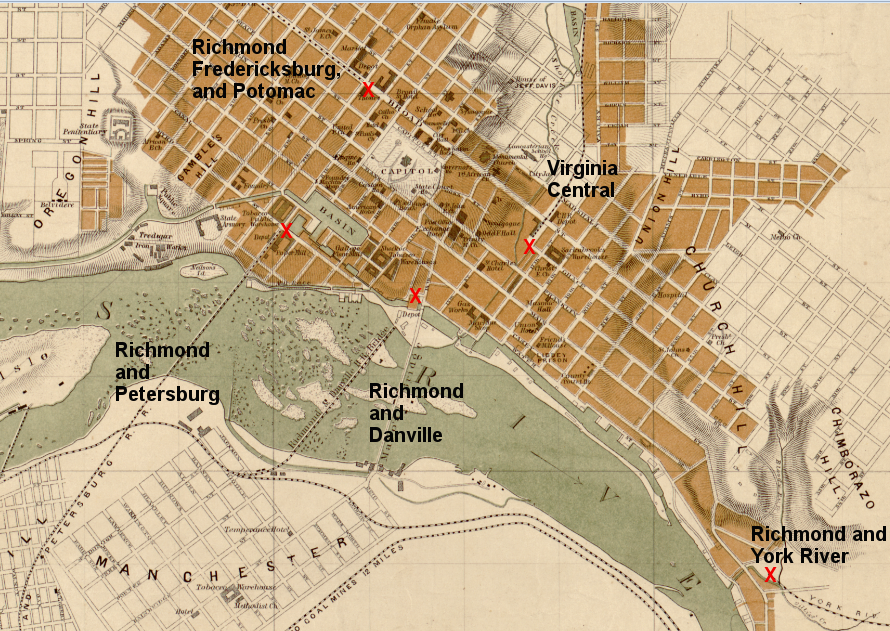

In Richmond, five different railroads had individual terminals in the city where passengers and freight were loaded onto trains. Each railroad built a separate station; there were no connections between the tracks of each railroad. The Chesterfield Railroad, carrying coal from the Midlothian mines, was a sixth unconnected railroad just outside the city.

there were six railroads in the Richmond area in 1861, without any joint terminals

Source: US Army Command and General Staff College, Rails to Oblivion: The Decline of Confederate Railroads in the Civil War

at the start of the Civil War, five railroads lacked a connection between their terminals in Richmond

Source: New York Public Library, Map showing the economic minerals along the route of the Chesapeake & Ohio Rail Way (1872)

Local officials discouraged rail lines from connecting with each other and carrying people/cargo directly through the city. Creating inefficiency by interrupting transport between competing rail lines created economic benefits for local businesses. They provided the wagons, horses, warehouses, and hotels required by passengers and goods traveling to their final destination, local officials supported local businesses, and the General Assembly did not mandate cooperation when issuing/revising railroad charters.

the five railroads that served Richmond in 1861 were not connected - each one had a separate terminal, so wagons carried cargo and passengers between them

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Richmond, Virginia

The Richmond and Petersburg Railroad built a bridge at its northern end across the James River to deliver/receive cargo on the Richmond waterfront. At its southern end, the railroad did not cross the Appomattox River to reach the center of Petersburg. The railroad's southern terminal was built on Pocahontas Island. Cargo and passengers were then required to go by wagon on a bridge across the river to connect with a different rail line.

At the start of the Civil War, the delays in transport at Petersburg constrained the delivery of supplies to support the Confederate Army. In response, the Petersburg Common Council authorized a direct rail connection across the Appomattox River, but required that it be used only for military traffic and must be removed at the end of the war.

The same action was taken in Richmond by its city council in 1861. It sought to limit the connections to temporary military uses only. Guaranteeing a return to inefficiency after the war would restore the jobs of teamsters who hauled goods by wagon, stagecoach drivers who carried passengers between terminals, and the businessmen who owned the companies:2

- Resolved: That the authorities of the State of Virginia be authorized to connect the railroads coming into the City, or any of them, by laying tracks through the streets of the City; said tracts to be used only for the purposes of the State, or of the Confederate States, during the war, and to he removed when no longer required for these purposes.

Main Street Station in Richmond was celebrated on a postage stamp in 2023

Source: U.S. Postal Service, U.S. Postal Service Reveals Stamps for 2023

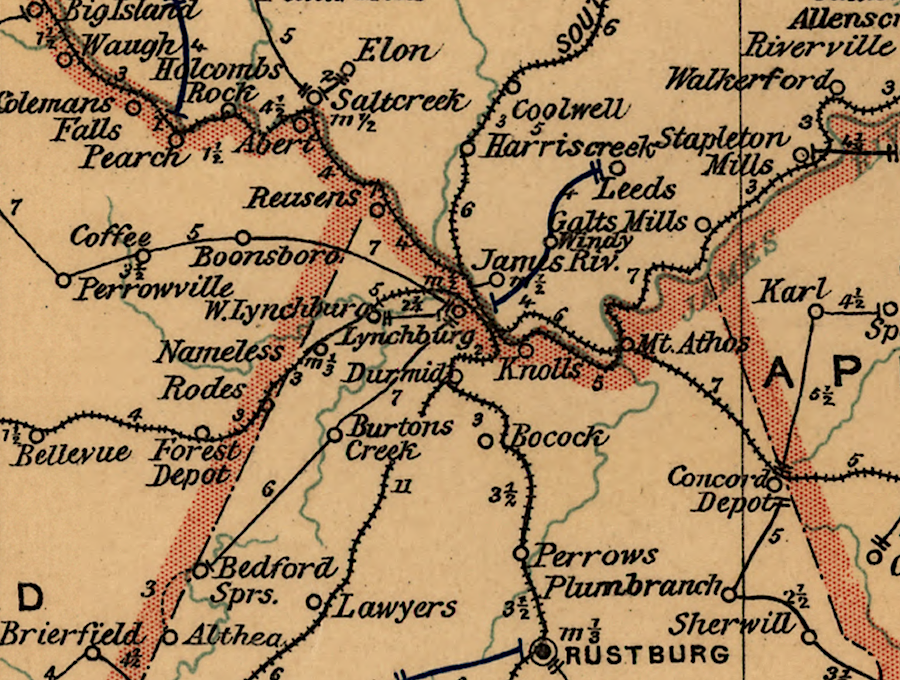

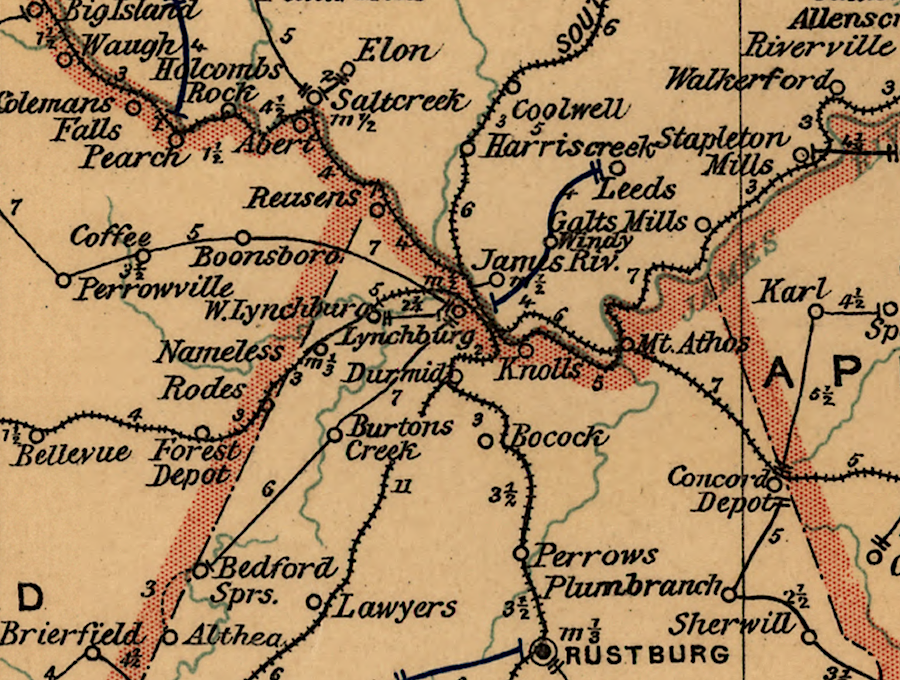

Lynchburg railroads in 1896

Source: Library of Congress, Post route map of the state of Virginia and West Virginia (1896)

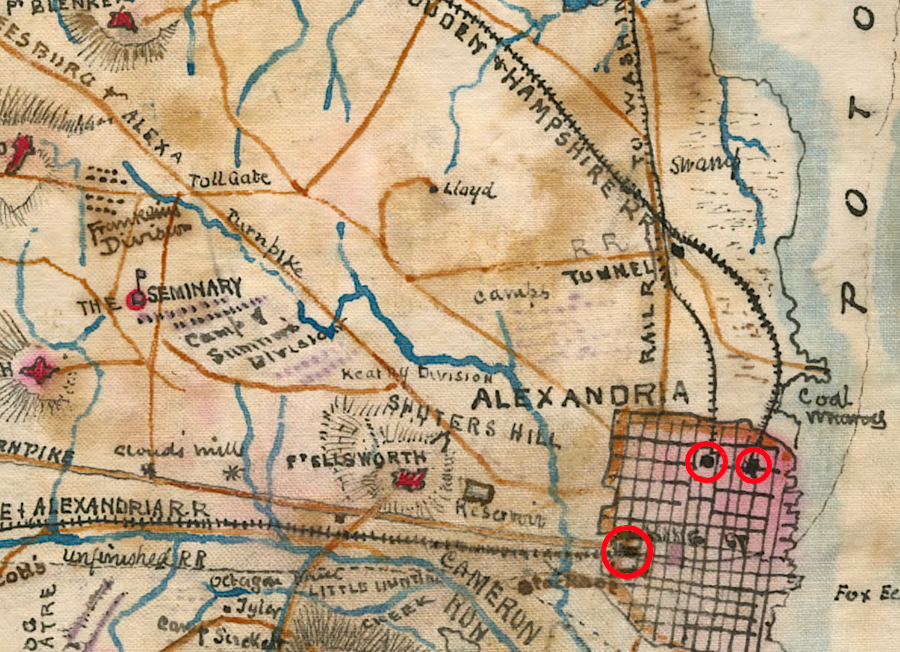

In Alexandria, the competing railroads also had separate terminals. As in Richmond, different investors were not inclined to share traffic with their rivals.

the US Military Railroad finally connected the three private railroads with separate stations in Alexandria

Source: Library of Congress, Map of n. eastern Virginia and vicinity of Washington ("McDowell Map," 1862)

The failure to connect railroads ensured wagon drivers ("draymen") had work hauling products between train stations, but it also had military consequences. Prior to the outbreak of fighting in the Civil War, Robert E. Lee - the military advisor to the governor of Virginia - was unable to get the owners of the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire (AL&H) railroad and the Orange and Alexandria (O&A) to build a piece of track connecting the railroads.

As a result, when the Yankees occupied Alexandria on March 24, two valuable locomotives were isolated on the AL&H. To keep them from the Yankees, the locomotives were driven west towards Leesburg. Before the Manassas Line was abandoned in March, 1862, the locomotives were removed from the AL&H and carried across Loudoun and Fauquier counties to the Manassas Gap railroad at Piedmont Station (now Delaplane).

Today, the old Manassas Gap Railroad is part of the Norfolk Southern. The track crossing the Blue Ridge between Manassas and Front Royal is known as the "B Line." Branches of the Piedmont Division of the Norfolk Southern are labeled in order, stretching south from Washington DC. The old Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire (today's Washington and Old Dominion biking trail) was the first branch line south of Washington, so it is the A Line. The second branch leaving at Manassas for the Shenandoah Valley became the B Line.

in 1872, the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad line was built parallel to the old Orange and Alexandria line, just west of Alexandria in modern Eisenhower Valley

Source: Library of Congress, Map of northern Virginia (1894)

After the Civil War, investors from outside Virginia gained control over different railroads. The out-of-state investors sought to increase traffic on their lines, and their preferred port cities were in Maryland and Pennsylvania rather than in Virginia. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad directed traffic to Baltimore near the northern end of the Chesapeake Bay, while the Pennsylvania Railroad sent traffic to Philadelphia on the Delaware River.

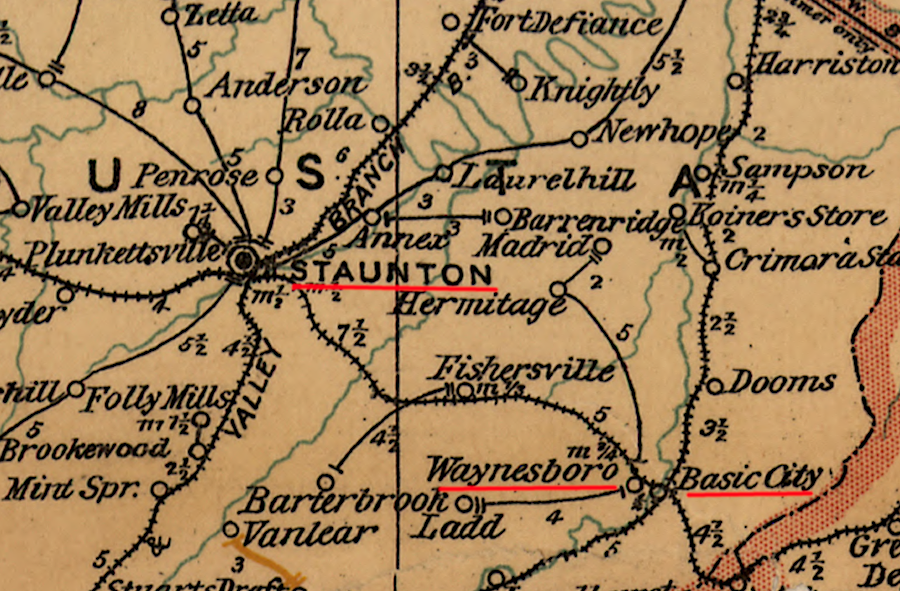

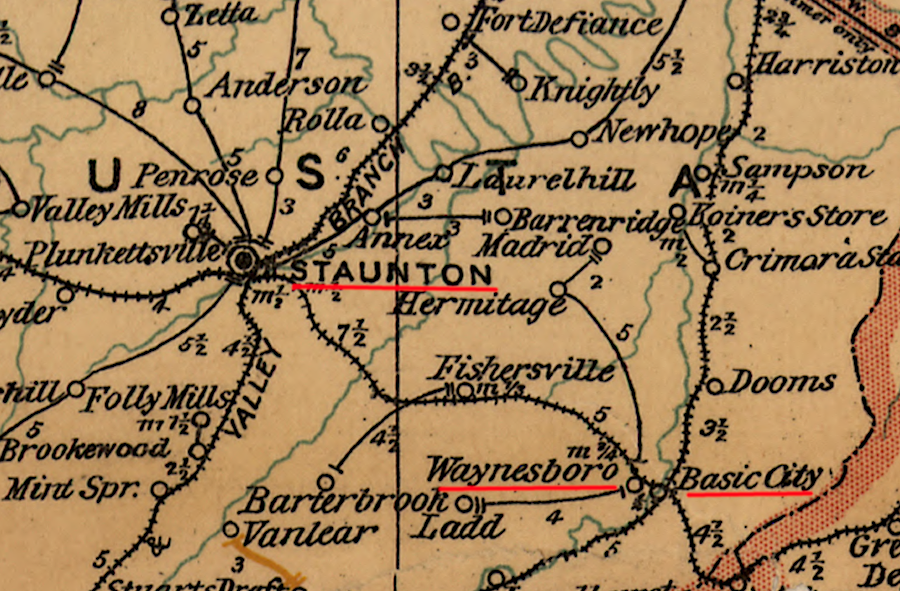

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad funded construction of the Valley Railroad, extending the old Manassas Gap Railroad west of Massanutten Mountain south to Staunton. The Pennsylvania Railroad financed construction of the rival Shenandoah Valley Railroad, with a connection to Hagerstown (Maryland) and Philadelphia.

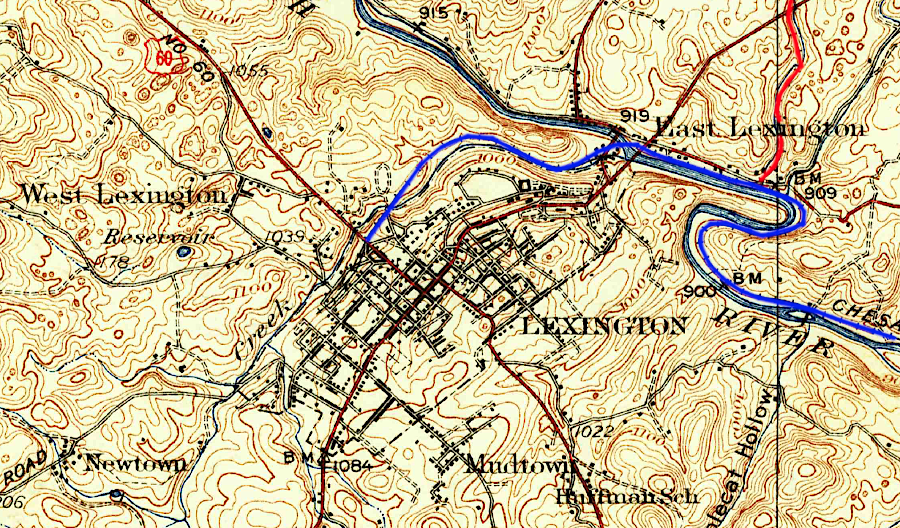

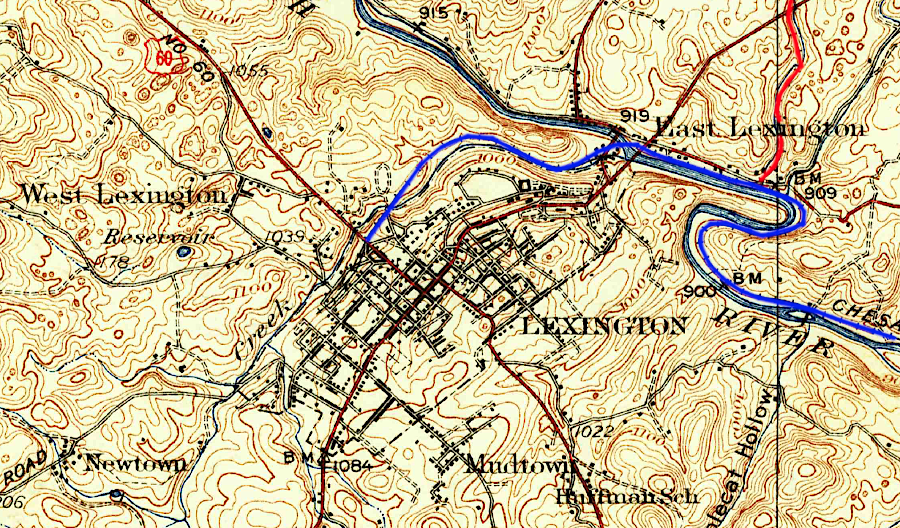

The Shenandoah Valley Railroad was located east of Massanutten Mountain to gain business from Virginia's iron furnaces, while the Valley Railroad connected the towns along the Valley Pike (now I-81). The Valley Railroad linked up with the old Virginia Central at Staunton, but construction further south ended at Lexington. Financial constraints stopped it short of its intended destination of Salem, where it could form a junction with the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad.

The Shenandoah Valley Railroad investors had more resources, and they completed that line south and linked to the Atlantic, Mississippi, and Ohio Railroad in 1881. Ultimately both lines were renamed the Norfolk and Western Railroad, and the junction where they joined developed into the city of Roanoke.

In 1883, the Valley Railroad finally reached Lexington. It connected just north of the Maury (North) River with a branch of the Richmond and Alleghany Railroad, leased by and later incorporated into the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railroad. The link meant that Lexington was served by two railroads until the Valley Railroad ended service south of Staunton in 1942.

both the Valley Railroad (red) and the Lexington Branch of the Richmond and Alleghany/Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad (blue) served Lexington between 1883-1942

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Lexington, VA 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1937)

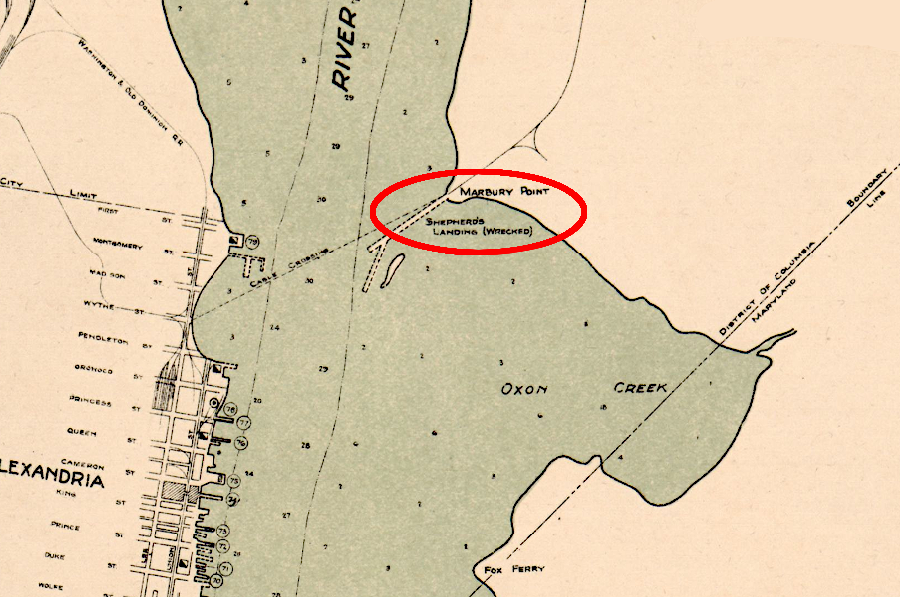

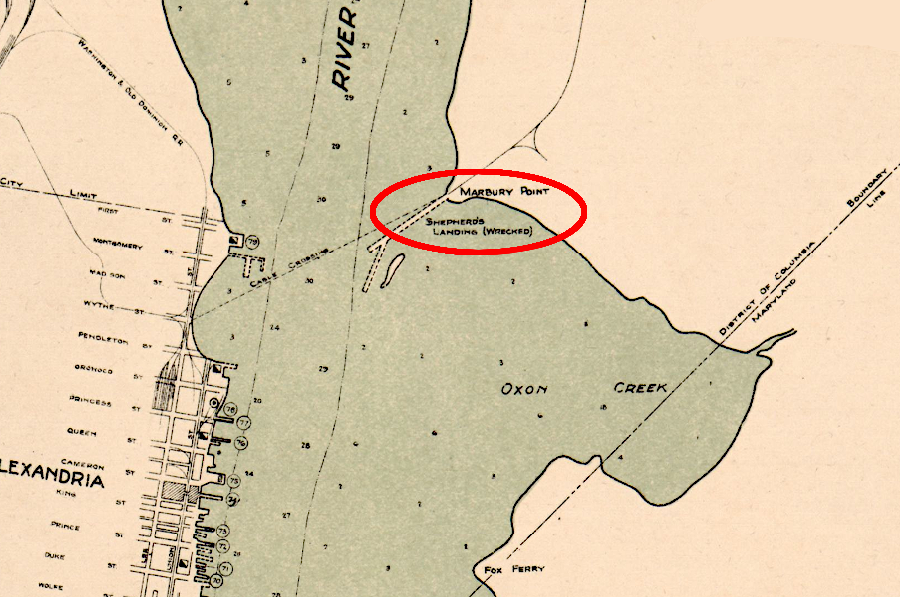

There was bitter competition between the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad to connect to Alexandria. Those northern lines sought monopoly control over crossing the Potomac River, to increase their traffic to southern states. During the Civil War, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad gained the right to use Long Bridge, but in 1870 the Federal government switched that right to just the Pennsylvania Railroad. In response, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad built the Alexandria Branch from Hyattsville, Maryland to Shepherd's Landing on the Potomac River. To cross the water, the B&O used car floats to ferry freight cars to a wharf in Alexandria from 1974-1906.

In 1906, six competing railroads opened Potomac Yard and started to interchange traffic there. The demand for increased rail capacity in World War II could not be accommodated by the existing infrastructure, so the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad built a railroad bridge across the river from Shepherd's Landing to Alexandria. The Emergency Bridge included a movable part to allow ships to pass, and that part was brought from a dismantled bridge in Michigan.

Trains of both the Pennsylvania and the Baltimore and Ohio railroads used the Emergency Bridge between 1942-1945, primarily to carry troops north.3

the US Army Corps of Engineers mapped Shepherd's Landing in 1923, facilitating planning for building the Emergency Bridge there in 1942

Source: Library of Congress, Port facilities at Washington D.C. & Alexandria, VA (US Army Corps of Engineers, 1923)

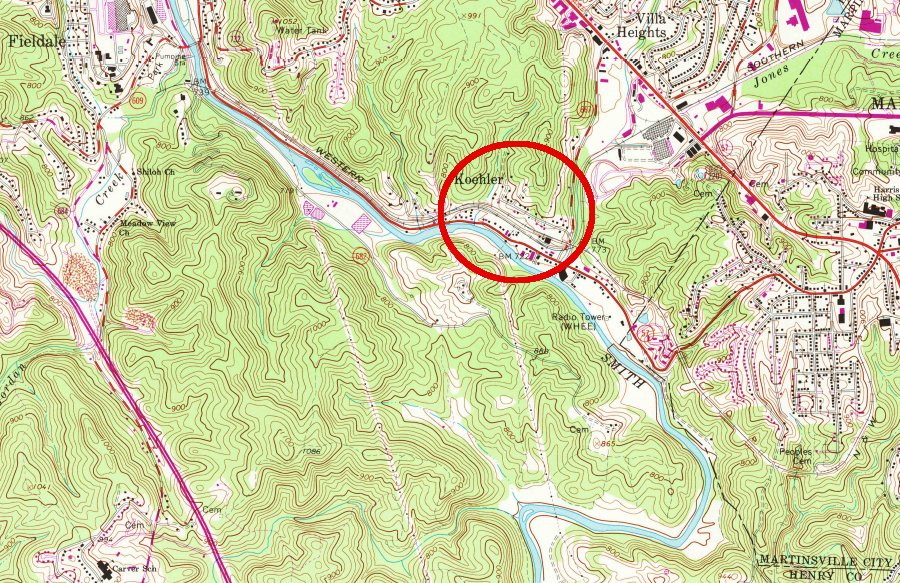

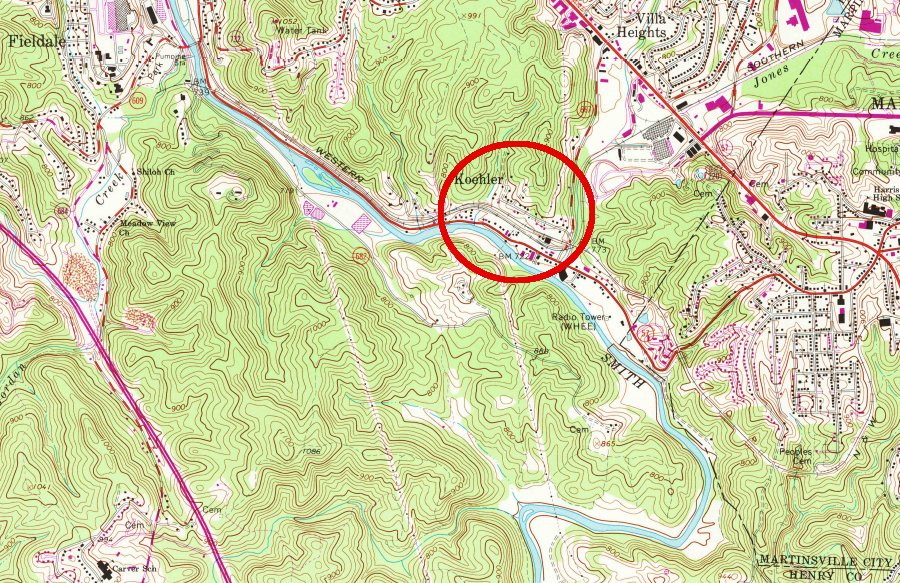

The smallest union station in Virginia was probably at Koehler. The Danville and Western Railway intersected with the Norfolk and Western's "Pumpkin Vine" route there.4

the Norfolk and Western Railroad and the Danville and Western Railway built a joint depot at Koehler, west of Martinsville

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Martinsville West, VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (1965)

Staunton and Waynesboro/Basic City each had two railroad connections in 1896

Source: Library of Congress, Post route map of the state of Virginia and West Virginia (1896

Lynchburg railroads in 1896

Source: Library of Congress, Post route map of the state of Virginia and West Virginia (1896)

Links

- City of Alexandria

- Richmond Magazine

References

1. Charles G. Siegel, "Orange & Alexandria Railroad - A Chronology," The Orange & Alexandria Railroad, http://www.nvcc.edu/home/csiegel/Chronology.htm (last checked July 4, 2016)

2. Meredith Bocian and John Salmon, "The Richmond and Petersburg Railroad during the Civil War," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, October 27, 2015, http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Richmond_and_Petersburg_Railroad_During_the_Civil_War_The; Lou Manarin, ed., Richmond at War: The Minutes of the City Council, 1861 – 1865, in Civil War Richmond, http://www.mdgorman.com/Other_Sites/city_council_minutes,_4_26_1861.htm (last checked July 3, 2020)

3. "The history of Baltimore & Ohio's Shepherd Branch," Classic Trains, December 14, 2001, https://ctr.trains.com/railroad-reference/operations/2001/12/the-history-of-baltimore-and-ohios-shepherd-branch (last checked March 29, 2020)

4. Kenneth Rickman, "History of the D&W," http://southern-railway.railfan.net/dw/ (last checked March 29, 2020)

in 1861, the three railroads serving Alexandria had three separate terminals

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the Battle of Fredericksburg, Va., Decr. 13, 1862 (by Robert Knox Sneden, 1862-65)

Railroads of Virginia

Virginia Places