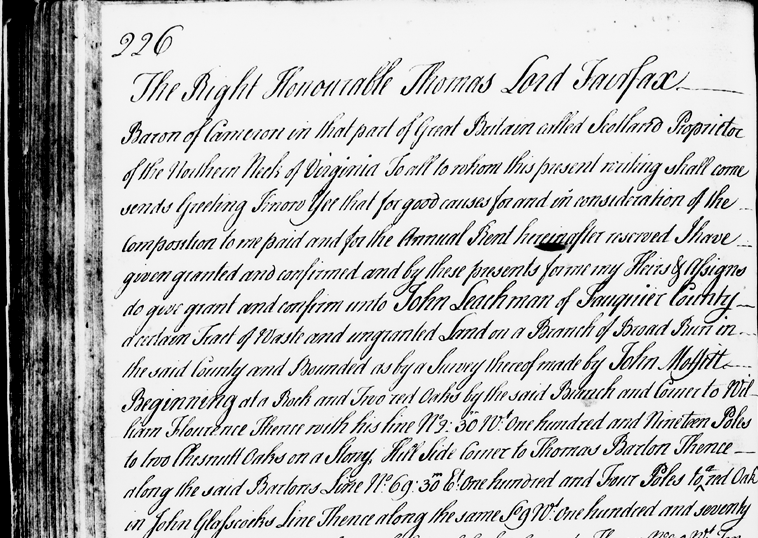

land patents were handwritten documents in the colonial era

Source: Library of Virginia, patent for Wren, James. grantee (April 5, 1773)

land patents were handwritten documents in the colonial era

Source: Library of Virginia, patent for Wren, James. grantee (April 5, 1773)

The English who settled in Virginia starting in 1607 asserted that they owned the land. During the colonial period, individual colonists acquired real property primarily through grants from the Virginia Company and then aby headrights, treasury rights, and military warrants.

With rare exceptions any pre-existing ownership rights of the Native Americans, the current occupants, were dismissed. At various times the English stated simply that they owned the land through Right of Discovery and Right of Conquest. Treaties were negotiated with different tribes in the 1600's and 1700's to extinguish Native American claims, but land was seized rather than purchased from the original inhabitants. The chain of title for parcels in Virginia starts with colonial records created by the English.

Charters issued by James I did acknowledge the land claims of the Spanish in the New World, based on prior settlement. The first charter issued to the Virginia Company in 1606 authorized the investors "

The Europeans who settled first at Jamestown were employees of the Virginia Company. The investors in that company controlled all the initial English land claims in the colony. That total ownership claim was altered by 1613, after which land titles for individuals were established by company land grants to individuals and to "particular plantations." After King James I revoked the Virginia Company's charter in 1624 and Virginia became a royal colony, land was privatized by treasury rights, headrights, land bounties used to recruit soldiers, and land grants awarded by kings in England and by colonial officials in Williamsburg.

The Virginia Company was not a successful business before it expired in 1624. The Spanish had found gold in the Caribbean, then seized vast wealth from organized Native American societies in Mexico and Peru - but there was no gold on the Coastal Plain of Virginia, and the paramount chiefdom led by Powhatan offered no stores of mineral wealth to exploit. When Captain Christophr Newport sailed back to England from Jamestown on June 22, 1607, the Susan Constant and Godspeed carried lumber and barrels of dirt that did not contain valuable minerals.

John Rolfe demonstrated how the company could make a profit by shipping tobacco in 1614. His crop was grown from Nicotiana tabacum seed. That might have been acquired while shipwrecked on Bermuda, or from sailors who visited Jamestown in 1611 or 12.

Rolfe demonstrated there was a demand for tobacco grown in Virginia rather than purchased from Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. The profitable crop helped the Virginia Company recognize that agriculture rather than the discovery of minerals could generate a positive return on investment.The investors realized that farming was the answer, and the Virginia Company had both land to grow tobacco and customers in England. The problem was finding enough laborers to plant and cure the tobacco in Virginia.

Tobacco farming required large amounts of land because the plant exhausted key nutrients in the soil, particularly nitrogen, in just 2-3 years. New fields had to be cleared and planted regularly, so growing tobacco required owning large tracts of land.

The Third Charter in 1612 had granted the company all lands between 34-41 degrees. In the Second Charter issued in 1609 the Virginia Company obtained all the land "from Sea to Sea West and North-west."2

The missing third key requirement was labor in Virginia. Producing tobacco required many people to do the actual farming. At the same time as tobacco revealed a basis for profit in Virginia, the company was struggling to find new workers willing to be transported across the Atlantic Ocean. Emigrating to Virginia was a high risk decision. When Captain Christopher Newport returned to Jamestown with the First Supply in Jamestown i 1608, only 38 of the 104 colonists he had left behind were still alive.

Negative reports from returning colonists discouraged even the poor in England from choosing to go to Virginia. After the Starving Time of 1609-1610, Lord de la Warre (as governor) and Sir Thomas Gates (as first marshal) had turned Jamestown into an armed camp with military discipline. They issued Laws Divine, Moral, and Martiall to control the behavior of the company's employees and soldiers.

Growing tobacco was a labor-intensive operation; large numbers of workers were needed to plant, weed, and harvest the crop. Owning a massive block of land in Virginia generated no profit for the investors unless there were farmers growing tobacco on that land. The Virginia Company needed to increase immigration to Virginia, and to decrease emigration of servants who had completed their time of required service.

The company adapted. Investors retained dreams of finding valuable minerals or generating profits from manufacturing items in Virginia such as glass, but the revised business plan took advantage of the company's greatest asset - its ownership of a vast amount of fertile land.

In 1613, Governor Sir Thomas Dale began to grant three-acre parcels to colonists willing to stay after their seven-year indentures expired. Those who stayed could work for themselves on their private three-acre plots, rather than serve the company by working full-time on its common land.

In 1616, colonists in Virginia ("ancient planters") were given 50 acres in exchange for remaining rather than returning to England. Since the Virginia Company had no cash to distribute as a dividend in 1616, investors were also each given rights to claim 50 acres. Another 50 acres were granted for each new share purchased in the joint stock company, for twelve pounds ten shillings per share. The right to purchase land, in exchange for a payment of twelve pounds ten shillings into the company's treasury, established the principle of land sales for cash.3

Any additional investment in the company became a speculation on the value of the land, rather than on the potential for company profits from manufacturing, mining, or trading.

In 1617, the company declared that all new immigrants to the colony who paid their own costs for transportation would be rewarded with 50 acres of land. Immigrants unable to pay their own costs would also be worth 50 acres each, but the immigrant would not get that land.

For each new immigrant ("head"), the company granted a "headright" to survey and own 50 acres of land to the person who financed the trip. The headrights could be sold, so ship captains and could sail home with cash for investors rather than paper claims to land that they did not desire to own.

The "headright" system did not provide 100% free land to the initial investor. Transportation costs were as high as six pounds per person in the 17th Century.

Englishmen interested in a free trip to Virginia could sign contracts to provide seven years of labor, earning 50 acres of land at the end of their term of service. The opportunity to own land was the primary attraction for colonists to risk a trip across the Atlantic Ocean to the colony in Virginia in the Seventeenth Century. In England, social and economic mobility was limited. Few of the farmworkers had an opportunity to acquire land and enter the gentry class. Travel to Virginia was risky, but the chance to end up as a landowner provided strong motivation.

In 1618, the dividend was increased to 100 acres/share. Colonists who had financed their own trip to Virginia before 1616 were also given rights to claim 100 acres. To qualify, new colonists had to stay three years or die in Virginia before three years were completed. The first 50 acres would be distributed in an initial division of land, and the additional 50 acres would be distributed once the initial division of land was occupied by colonists:4

The Virginia Company also invited investors to create "particular plantations" or "hundreds" in the colony, separate from the company-managed communities such as Jamestown and Henricus. The company granted large amounts of land to investors willing to recruit settlers and establish new communities in the colony. Those communities would not be responsible to company officials; decisions made in Jamestown would not apply to the particular plantations.

The settlement of Bermuda set an example of providing investors some extra control over the settlements they sponsored. The island was surveyed and specific parcels of land called "tribes" (later called "parishes") were allocated to individual investors.

In Virginia, those who established particular plantations could also be company officials. The decision to create independent units within the colonies created confusing loyalties and conflicts of interest, but did stimulate some of the company's investors to provide new funding for colonization.

An investor who chose to fund a "particular plantation" rather than buy more shares in the Virginia Company was betting on the success of colonizing Virginia, independently from betting on the success of the Virginia Company. Tobacco could be grown profitably and shipped to market in Europe, and doing so on private land minimized the risks that the Virginia Company might not generate an overall profit.

to maximize profit from tobacco production, colonial investors acquired title to private parcels separate from the Virginia Company's lands

Source: Colonial National Historical Park, National Park Service, Tobacco Production

By creating private land rights, the London Company traded total control over its land in exchange for profits from handling tobacco and collecting the equivalent of property taxes ("quitrents") at the rate of 2 shillings/100 acres. It was a long-term strategy.

The Virginia Company loosened its control even more in 1618. A faction of investors led by Sir Thomas Sandys outmaneuvered its opponents in the company. They forced Sir Thomas Smith out of the role of Treasurer, which was equivalent to Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Office, and issued the 1618 Charter of Orders, Lawes, and Privileges.

That "Great Charter" was a set of instructions from the investors in London, not a fourth charter from the king. It gave greater responsibility for local government to the colonists, and authorize the first General Assembly which met in 1619. Under Sir Thomas Sandys, the company expected that granting land and freedoms to colonists would increase the population enough so investors could finally make a profit.5

Governor Wyatt issued patents to land based on headright claims until the Virginia Company failed. After Charles I took direct control of the colony in 1625, his appointed royal governors continued to issue headrights. The colony, rather than the private company, collected the annual quitrents of 2 shillings/100 acres.

Quitrents were based upon the concept that the King of England or a feudal lord was entitled to require a person to provide military services in exchange for the right to live on the land. That claim could be replaced by the resident's agreement to pay quitrents instead. The authorization of quitrents, with land held in "free and common soccage" without a commitment of personal service, permitted a resident to sell the right to live on the land.

So long as the next person paid the quitrents, land tenure no longer was limited to members of a family who had made an obligation to a feudal lord. Quitrents facilitated the creation of a real estate market, with willing buyers and sellers who did not need the lord's permission for a transaction.

In the Virginia colony, quitrents were supposed to be collected by the local sheriff and used to defray the costs of administering the colony. Quitrents and per-capita (capitation) taxes were raised as needed so England did not need to pay colonial officials from the treasury in London. When Lord Fairfax acquired the large grant of the Northern Neck, he collected the quitrents from that area.

Collection of quitrents outside of the Fairfax Grant ended in 1777. Practically, the 1777 law also ended quitrent collection within the Fairfax Grant by allowing anyone who paid a quitrent there to deduct it from their taxes.

The award of 50 acres for everyone imported into Virginia incentivized people in England to sign indentures and spurred wealthy individuals to find and transport indentured servants to Virginia. Within 50 years, 70,000 people came to Chesapeake region.6

Servants would work 3-7 years clearing new land, moving the edge of English settlement further west into the North American continent and increasing the volume of tobacco exports. At the end of their term of indenture, the contracts usually required that the freed servant be given some basic clothing and farming equipment.

There was no automatic grant of land to immigrants. If an indentured servant had been transported by a investor who claimed the 50-acre headright, then that servant did not acquire title to any land despite their term of service.

Without land of their own, the freed servants had four choices. The first three were to return to England, negotiate a deal to work for someone else in exchange for support and wages, or find unclaimed land on the edge of settlement and become a squatter.

The fourth option was to purchase low-cost land (typically on credit), then "improve" it by cutting down the trees and preparing fields suitable for growing crops such as corn and tobacco. That was the dream of many of those who signed indentures, trading up to seven years of labor for the chance to become a landowner. Those who lived through their period of indenture struggled to become landowners, but the potential in Virginia was greater than that in England until the 1660's.

As the forested frontier was converted into farms, many of the servants managed to become landowners. In Virginia, they could provide their children a better opportunity at gaining wealth. The risks were high, but so were the rewards.

The former servants may have been cash poor, but they could buy land on credit from one of the many members of the gentry. The gentry were the wealthy top 5% at the top of Virginia's stratified society.

Some were "Cavaliers," supporters of King Charles I who had moved to Virginia during the English Civil War. They arrived with sufficient wealth to acquire large tracts of land, speculating that it would gain in value over time. The investment was successful when someone acquired title to large blocks of land at a low cost per acre, and then to found settlers willing to pay a higher price per acre for small parcels.

Abuses of the headright system allowed some people to expand legitimate claims. Some ship captains arranged for county officials to award headrights for sailors who came to Virginia but did not stay. Sometimes both a ship captain and a person paying the transportation costs obtained headrights for the same individual(s) transported to Virginia. In most straightforward corruption, a claim could be filed for more immigrants than actually arrived in Virginia and granted by the Secretary of the Colony in exchange for other favors.

Virginia planters who imported slave labor from the West Indies or directly from Africa were awarded 50 acres per slave, just as they were awarded 50 acres per indentured servant. Both large and small landowners imported slaves, or purchased them from ship captains who brought them to the colony for sale.

George Menefie was the first to claim a large number of headrights for one shipment of slaves, obtaining 1,150 acres for the 23 slaves he imported along with 37 other (white) servants in 1638. The headright claims for the indentured servants listed the names of the individuals, but the claims for slaves rarely identified individual slaves.7

The colony had an excess of land and a shortage of people. It was public policy to encourage population growth through immigration, and to induce immigration through promises of cheap land. This policy was not limited to the colonial era. The United States passed the Homestead Act in 1864, to provide free land and encourage immigration to the unsettled western area. The Homestead Law was not repealed until 1976, with passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act.

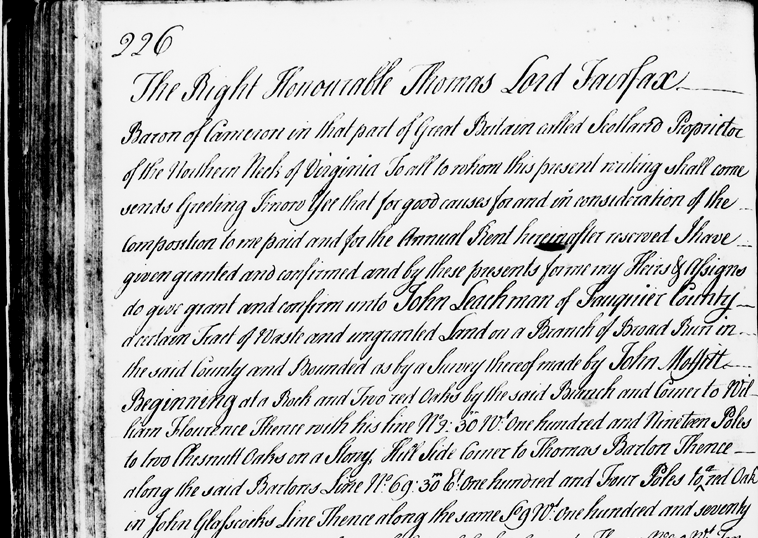

in the Northern Neck, Lord Fairfax could sell land in whatever sized parcels he wished, without regard to headrights or treasury rights

Source: Library of Virginia, patent for Crossthwait, William. grantee. (November 10, 1751)

Technically, the headrights system lasted from 1618 until cancelled by the General Assembly in 1779. Starting in 1699, after European immigrants became harder and harder to attract, the colony began to sell "treasury rights." They allowed purchasers to claim 50 acres for 5 shillings, without having to import an immigrant.8

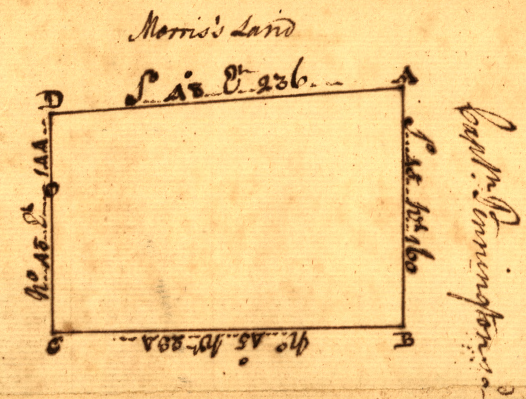

The process of converting a headright or treasury right into a deed of land ownership involved several steps. In theory, the process prevented invalid headright or treasury right documents from being used to acquire land.

The process started when the person claiming headrights went to a county court and got the justices to certify how many people had been imported. That certificate of importation would be provided to the Secretary of the colony in Jamestown or, after 1699, in Williamsburg. The Secretary then issued a document, a "right," certifying how many acres were authorized for survey. After 1699, a person could purchase a treasury "right" directly from the Secretary.

The documentation from the Secretary, the "right" based on importing people (headright) or a purchase (treasury right), would be delivered to the county surveyor. That person, or someone hired to do the work, would identify parcels matching the total acreage authorized. The county surveyor, an appointed official responsible to the county court, would deliver the survey to the Secretary in Jamestown/Williamsburg.

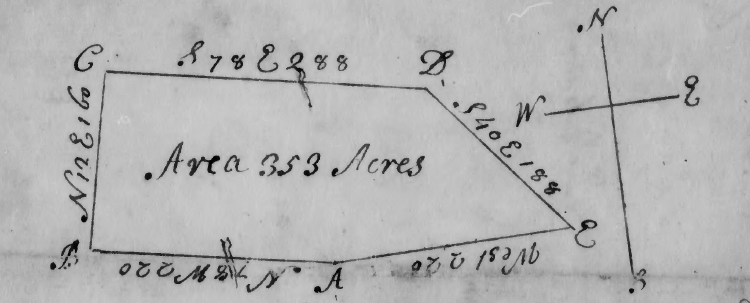

colonial surveys were simple documents, referencing features on the ground such as red oak trees

Source: Library of Virginia, survey for Wren, James. grantee (April 5, 1773)

The Secretary of the Colony prepared a "patent" (land deed, known later as a "grant") based on the survey. He kept one copy and forwarded another to the Governor. After the Governor approved the patent, the copy would be delivered to the new landowner.

The chain of title starts with the patent issued by the Secretary and bound into books at his office. Land was subdivided, re-surveyed, and re-sold over the years, but the Secretary was not involved in subsequent land transfers. Later deeds and surveys documenting new parcels and new ownership were recorded in the files of just the local county court.

Once a patent was issued, the land was supposed to be settled within a period of three years. Unless trees were cleared and crops planted, ownership was supposed revert back to the colony. That requirement was designed to spur settlement and deter land speculation, and affected individual "minor" grants.

The rules were applied differently to larger grants. Land speculation was a major part of the gentry's acquisition of wealth and power throughout the colonial period.

The son of King Charles I awarded the largest land grant. The son was rallying supporters to eventually defeat the Puritans led by Oliver Cromwell, who had deposed Charles I and executed him. In September 1649 the son, who was in exile in France but became King Charles II in 1660, awarded all the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers to seven supporters. Eventually the sixth Lord Fairfax inherited all the claims, and the Fairfax Grant totaled 5.2 million acres.

In the 1700's, the governor and his Council of State gave large grants to lands in the Piedmont to members of the gentry. The Tidewater elite controlled the Council that (together with the governor) issued land orders and grants for chunks of land measured in tens of thousands of acres. The governor and Council extended deadlines required for settling large grants, such as the 100,000 acres given to Jost Hite in 1730, when the land speculators were unable to recruit the number of settlers required within the time frame of the land order.

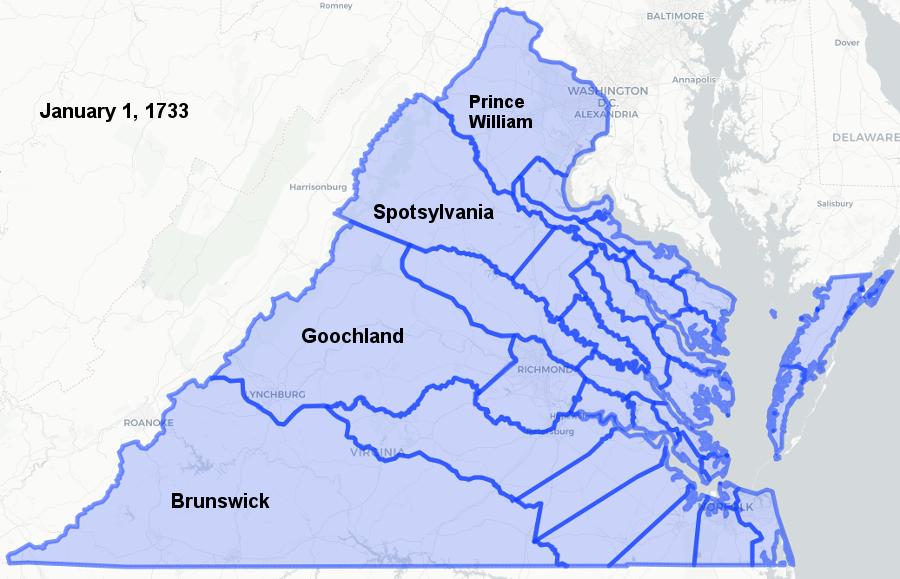

The Williamsburg officials also altered the standard procedures for acquiring clear title to land, in order to stimulate settlement west of the Blue Ridge in the 1730's. There were no county courts administering land west of the Blue Ridge until the creation of Orange County in 1734.

Treasury rights and headrights required actions by county surveyors and justices of the peace, but in 1730 Governor Gooch and the Council calculated that the threat of French and Native American incursion on the western edge of the colony was too great to wait for the General Assembly to establish new counties. They issued nine vaguely-worded land orders for 385,000 acres to land speculators between 1730-1732, in the expectation that the speculators could recruit Protestant, white settlers to establish small farms west of the Blue Ridge.

Governor Gooch and the Council were willing to give large land grants west of the Blue Ridge to people other than the Tidewater elite, who had monopolized grants of large parcels in the Piedmont east of the Blue Ridge. A primary concern was to populate the Shenandoah Valley with people who would be loyal to the Virginia colonial government before the French could establish control there by working in partnership with their Shawnee and Delaware allies.

until Orange County was created in 1734, no Virginia county court or surveyor operated west of the Blue Ridge

Source: Newberry Library, Atlas of Historical County Boundaries - Virginia

The Virginia gentry dominated the Council even more than it controlled the House of Burgesses. Though the governor was appointed by the king in London and given instructions to direct the royal interests in the colony, land policy ended up being designed to increase the wealth of the Virginia elite and governors accommodated themselves to the "First Families of Virginia" (FFVs). The process for transferring small parcels to land claimants via headrights and treasury rights was decentralized to the county level, but the Council and governor retained the power to award larger land grants:10

Those who obtained warrants, surveyed tracts, and actually acquired the documents which certified their exclusive ownership of a particular parcel (land patents), might sell 100 acres for as much as three pounds (60 shillings). For land purchased by a treasury right at 10 shillings/100 acres, that was a 600% markup - but far cheaper than the price required for land in Pennsylvania, which sold at 10-15 pounds/100 acres. When Virginia created a Land Office in 1779 and began to sell unappropriated western lands to finance Revolutionary War costs, the price was 40 pounds for 100 acres.11

On the edge of settlement, freed indentured servants and immigrants moving south from Pennsylvania established their own codes for acquiring land. By occupying land far from a county court, new settlers could clear forests and create farms without paying anyone for the land rights.

The first colonists to occupy a valley would select the best land for a farm, using their knowledge of different tree species to recognize sites with the most fertile soil. Planting a field demonstrated a commitment to occupy land, and established a "corn right" for 100 acres. Building a cabin created a "cabin right." Cutting down trees defined boundaries of other claimed land, known colloquially as a "tomahawk right."

Public awareness of a claim, and its boundaries, was a key to acquiring title to land in colonial Virginia. Witness trees and surveyor's monuments showed responsibility of development had been shifted from the king/queen in London. The transfer to private ownership was a public process that ended with a document. The word for that document, "patent," was derived from the Latin word for "open."

The patent granted all rights for further development of parcel to new owner. Colonial governors were supposed to require that at least three out of every 50 acres was improved/cultivated before transferring the rights of the king/queen. Building a 16 x 20 foot "claim house" qualified as improvement, but no one had to live on the land in person.

Colonists thought cultivating the land generated a right to own the land. Claims of Native American, based on use of hunting/grazing without obvious transformation of the landscape, were finessed.12

Backcountry land claims were large enough to support a family. Later settlers would generally respect such claims, unless they were so extensive that the boundaries reflected an effort to "lock up" high-quality land for speculation rather than actual use, and choose other property to carve their farms out of the forest.

A person would arrive, often years later and assert the land was their property, based upon some legal documentation processed at the county court or further away in Williamsburg. At that point the first settlers had two choices. They could abandon their farm and move further west, or agree to pay for the land.

Abandoned farms might have higher theoretical value, since land was cleared and some fences and buildings might still be usable, but those with a legal right then had to find a buyer. Squatters who chose to stay were charged a higher price than they would have paid for a treasury right, but typically paid nothing for years of previous use and might receive generous terms to pay over several years.

A third option, to resist the claim of the person with legal rights to the land, was tried at least once. George Washington visited western Pennsylvania in 1784, and found squatters on lands he had been awarded for his service in the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. The occupants were Scotch-Irish Presbyterians who had lived there for a decade.

They felt their improvements, and resistance to incursions by Native Americans, qualified them to be owners rather than renters with an obligation to pay an absentee landlord. Washington's prominence as the military hero of the American Revolution did not awe the group, who called themselves the Covenanters after Presbyterian Scots who had opposed Charles I in the 1640's. After Washington made clear that he had the resources to ensure his ownership of the land through the courts, 13 of the Covenanters decided it would be better to pay and acquire clear title.

However, Washington drove too hard a bargain and set a price of twenty-five shillings an acre. It could be paid in three annual installments, but he insisted on interest. The Covenanters refused to pay, Washington filed suit in Pennsylvania court in 1786, and a jury awarded him title to the 13 farms. The Covenanters maintained their righteous attitude and abandoned their farms rather than pay George Washington. He still owned the farms when he died in 1799.13

On the Northern Neck, there was a slightly different process for selling land. Charles II granted that territory to six allies in 1649, and had the power to control land transfers after the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy. Lord Culpeper ended up as the primary owner of that grant, as well as governor of Virginia.

Demand for land north of the Rappahannock River increased during his lifetime, but he received little revenue from the grant. There were two major land sales completed before 1689, and they were handled by Lord Culpeper in England. After he died in 1689, his wife Margaret Culpeper inherited his 5/6th's share. Her daughter owned the remaining 1/6th share. Thomas Sixth Lord Fairfax eventually began to manage the Northern Neck land claims for his wife and mother-in-law.

Lord Fairfax appointed land agents who lived on the Northern Neck to sell parcels from what became known as the Fairfax Grant. The land agents for the proprietor included Philip Ludwell, George Brent, and William Fitzhugh. They processed the paperwork for Northern Neck grants (i.e., land sales) rather than the Secretary and Governor in Jamestown/Williamsburg.

Warrants authorizing surveys of parcels within the boundaries of the Fairfax Grant could be provided to surveyors other than the official county surveyors. George Washington completed several in Frederick, Hampshire, and other counties outside of Culpeper where he was the county surveyor in 1749-50.14

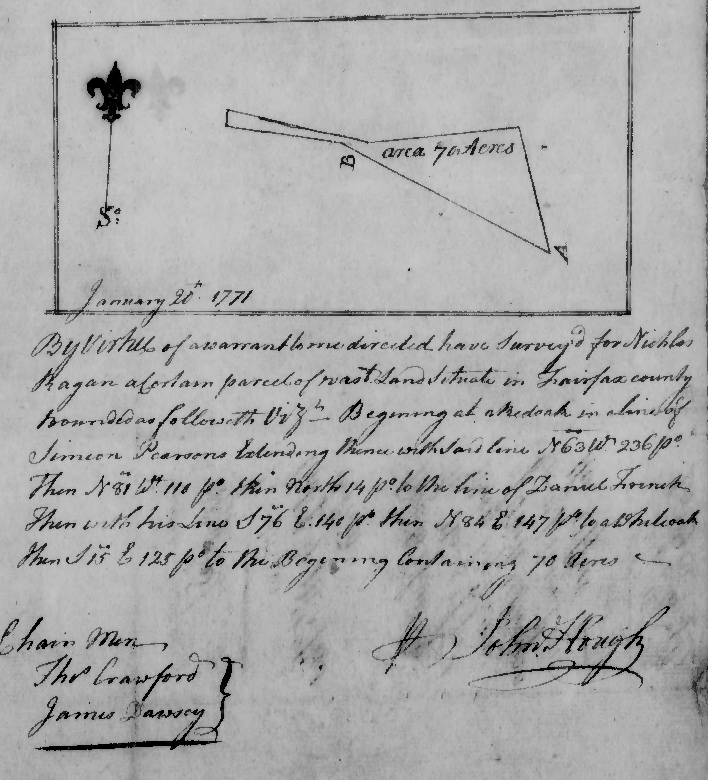

George Washington surveyed parcels pursuant to warrants from the Proprietors Office

Source: Library of Congress, Plat of survey for John Lindsey of 223 acres in Frederick County, Va. (by George Washington, 1750)

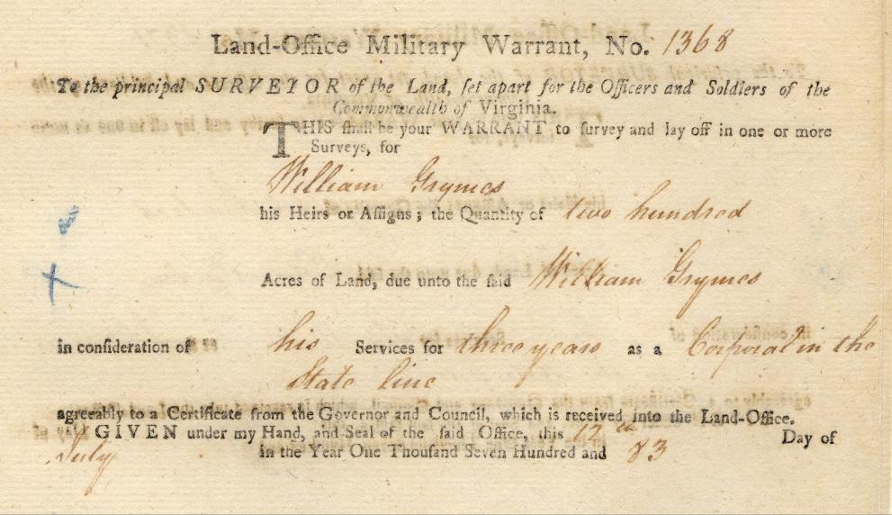

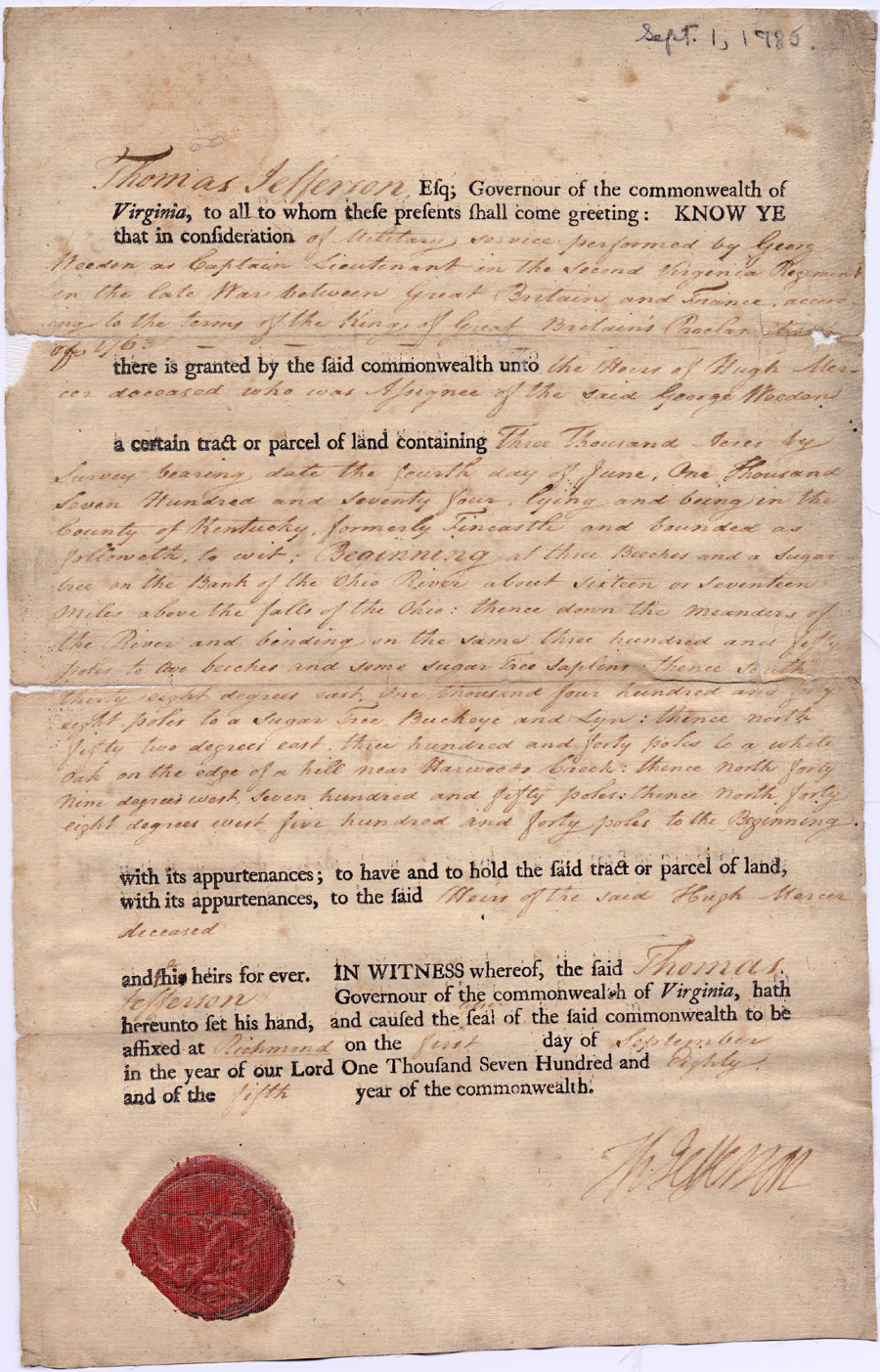

Virginians could also acquire land through special military service in Lord Dunmore's War, the French and Indian War, and the Revolutionary War. Annual, routine militia service did not qualify for special compensation. To recruit the soldiers and officers, Virginia's General Assembly authorized issuing military warrants that could be used for future land grants.

When Governor Dunmore fled Williamsburg in June, 1775, the process for approving surveys and issuing grants was interrupted.

The General Assembly passed a land law on May 3, 1779 to create a Land Office that could process land bounties awarded to soldiers who enlisted in the state forces or Continental Army. The land law also made it possible for holders of warrants and surveys issued while Virginia was still a colony to obtain a deed, and for the new state to sell land for cash:15

On June 22, 1779, over three years after declaring independence from Great Britain, the General Assembly authorized giving away parcels of land to attract volunteers to serve during the Revolutionary War. All lands within the state could be claimed.

To qualify for a land bounty, a soldier had to shift from short-term local militia duty and commit to serving for three continuous years in the State Line (within Virginia) or Continental Line (which served primarily in other states, until the 1781 Yorktown campaign). Men could also serve as sailors in the State Navy. For many families, the continuous commitment took a key worker away from the farm for three harvest seasons.

After the military service was completed, affidavits testifying that a person qualified for the bonus were submitted to the governor. As described by the Library of Virginia:16

William Grymes earned 200 acres from his Revolutionary War military service as a corporal in the State Line

Source: Kentucky Secretary of State, Revolutionary War Warrant 1368.0

Documents to authorize veterans of their heirs to claim land based on military service were issued between July 14, 1782 - August 5, 1876. Heirs were entitled if the soldier or sailor died while in the military, prior to completing three continuous years of service. Descendants claiming their ancestor was entitled to a land bounty had to prove 1) the ancestor met the qualifications and 2) they were the legal heirs entitled to exercise the military warrant.

Many soldiers sold their military warrants for quick cash, soon after getting the documents. Land speculators with capital to invest, including George Washington, purchased many of the military warrants at a discount. Years later, the speculators used them to acquire tracts and then sell the land for a profit.

The Kentucky Secretary of State "Frequently Asked Questions" page explains how military warrants were converted into land. The process for the Revolutionary War warrants also applied to warrants issued for Lord Dunmore's War in 1774 and the earlier French and Indian War.17

land grants were used to recruit soldiers and officers to serve during the French and Indian War

Source: Library of Congress, Three-thousand acre land grant to the heirs of Hugh Mercer, Kentucky County, Virginia