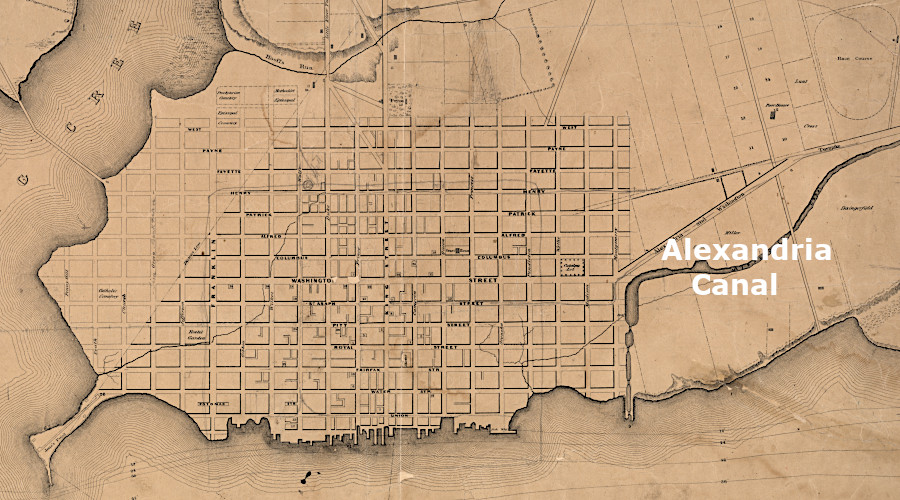

the Alexandria Canal connected the city to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the town of Alexandria, D.C. with the environs (Maskell C. Ewing, 1845)

the Alexandria Canal connected the city to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the town of Alexandria, D.C. with the environs (Maskell C. Ewing, 1845)

Alexandria was founded in 1749 with the expectation that the site, just downstream from the Fall Line, would develop into a bustling port city. To stimulate trade, primarily the export of wheat, corn, meat, and other agricultural products, local merchants invested in building a transportation network that extended deep into the countryside of Northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley. Good turnpikes, railroads, and canals incentivized farmers to deliver products to Alexandria rather than the competing port cities of Baltimore, Georgetown, and Fredericksburg.

The first attempt to build a canal on the Potomac River was led by George Washington. The Potowmack Canal was intended to bypass Great Falls, so freight cargoes could float down the Potomac River to the ports of Georgetown and Alexandria. That canal project failed, but the later Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal succeeded in connecting Georgetown to Harpers Ferry and further up the Potomac River.

Since the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was built on the northern side of the Potomac River, Georgetown merchants got first crack at the trade coming down the canal. The narrow canal boats were not designed to travel in the wide Potomac River downstream from Georgetown. All cargo brought downstream to be shipped to customers within the Chesapeake Bay, along the Atlantic Ocean coastline, on Caribbean islands, or overseas in Europe stopped first at Georgetown. Barrels of corn and wheat, forest products, and other cargo carried on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal could be moved past Georgetown by wagon to Alexandria via the Long Bridge, but that added expense and delay.

Ships sailing up the Potomac River, with manufactured goods such as textiles, glass and ceramics plus luxury items such as wine, found it convenient to dock at Georgetown. They could load up there with cargo brought down the canal. The Federal government helped Georgetown compete with Alexandria to capture shipping trade, by enhancing the channel in the Potomac River near Georgetown.

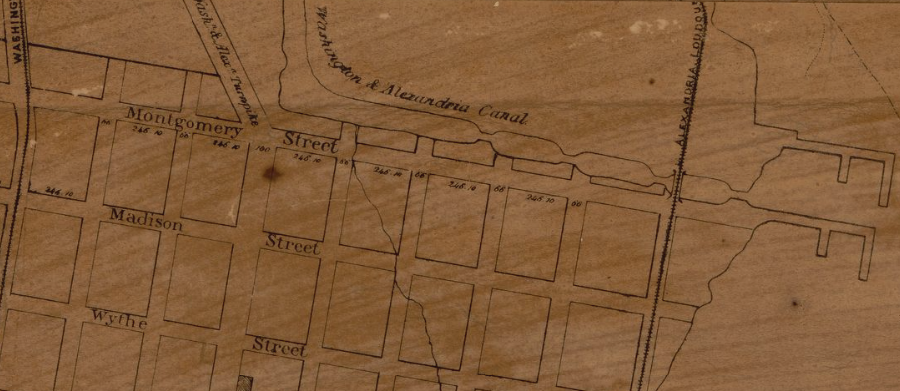

The US Congress authorized construction of a causeway in 1805 between the Virginia shoreline and Analostan (modern Teddy Roosevelt) Island. That was intended to divert water towards the Georgetown side of the river, with the extra flow expected to wash channel-blocking sediment downstream. Large ships that docked at Alexandria had struggled to navigate the remaining shallow channel of the Potomac River, and to pass through Long Bridge.

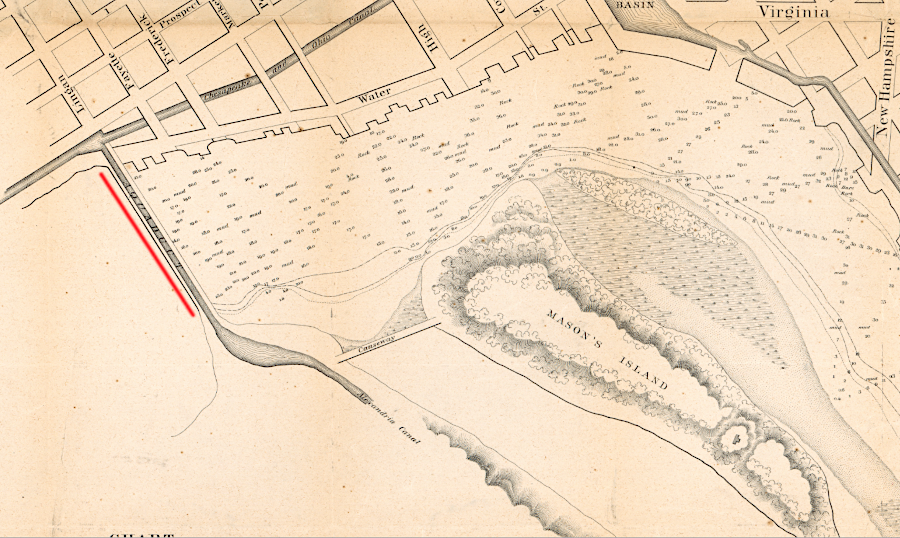

To attract more shipping business to Alexandria, and to enhance the potential for mills and bakeries to process corn and wheat shipped downs the Potomac River, city leaders proposed to build the seven-mile Alexandria Canal. It was designed to provide canal boats a safe water route from Georgetown to the ocean-going sailing ships docked at Alexandria.

Alexandria officials had to overcome opposition to the proposed Alexandria Canal by Georgetown merchants. who wanted to retain a monopoly on the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal trade. The US Congress had ultimate responsibility for deciding on transportation funding requests made by the two cities within the boundaries of the District of Columbia. Alexandria was part of the District of Columbia between 1800-1847, and Virginia officials were willing to finance transportation infrastructure only within the state's boundaries.

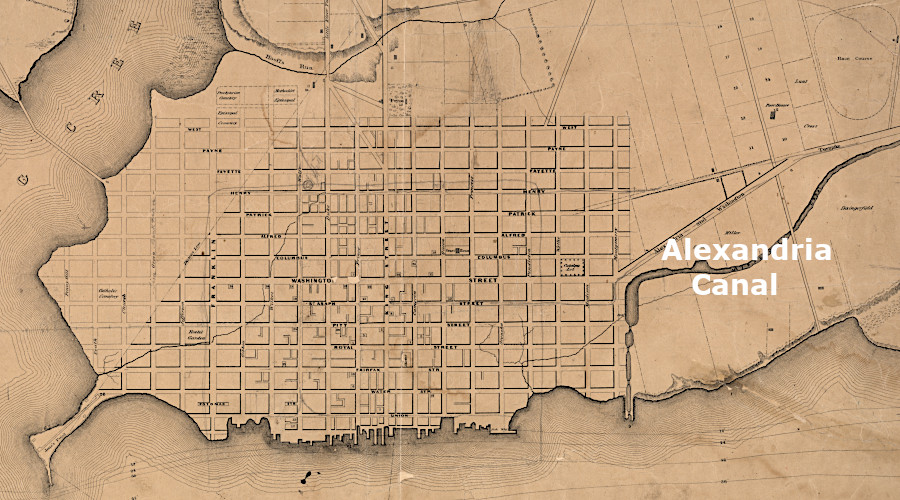

The city got some funding in part from the Federal government and the Alexandria Canal opened on December 2, 1843. It included a bridge across the Potomac River so boats could float from the downstream end of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in Georgetown to the Virginia shoreline. Most of the canal was a standard ditch. There were four locks in Alexandria between Montgomery Street and the shoreline of the Potomac River, so boats could be raised/lowered in stages from sea level.

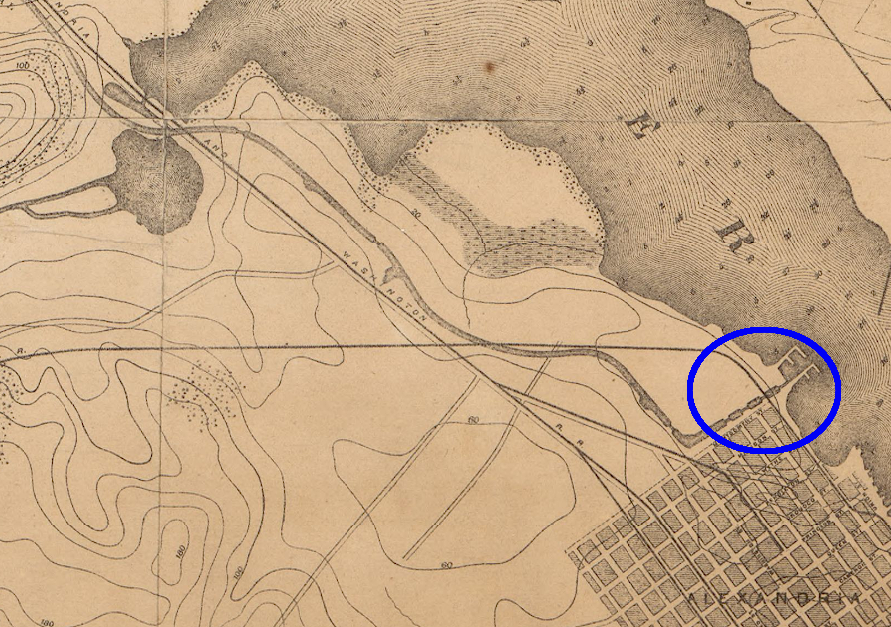

four locks in Alexandria, including a watergate, brought canal boats down to the level of the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the city of Washington in the District of Columbia (William Forsyth, 1876)

four locks changed the water level in the Alexandria Canal to equal the water level of the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the town of Alexandria, D.C. with the environs (Maskell C. Ewing, 1845)

The Aqueduct Bridge was made of wood that had been treated with bichloride of mercury to "kyanize" it. Chemical treatment reduced the speed at which the wooden bridge decayed:1

canal boats floated across the Potomac River on the Aqueduct Bridge

Source: Library of Congress, Chart of the head of navigation of the Potomac River (1857)

barge using the Aqueduct Bridge across the Potomac River

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Capital engineers: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the development of Washington, D.C. 1790-2004 (p.34)

Once the slice of Virginia within the District of Columbia was retroceded to Virginia in 1847, the state purchased Alexandria Canal bonds. That relieved the town of much of its debt.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal reached Cumberland, Maryland in 1850, and shipment of coal downstream to Georgetown and Alexandria increased. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal competed with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The extra coal traffic helped to offset diversion of agricultural traffic to Baltimore by the railroad.2

The original Aqueduct Bridge was designed exclusively for canal boat traffic across the Potomac River. The wooden flooring leaked, but the canal was functional.

the first Aqueduct Bridge was designed exclusively for use by canal boats, and not for people, horses, or wagons

Source: Library of Congress, Aqueduct of Potomac, Georgetown, D.C. (by Frederick Dielman, 1865) and Washington, D.C. Closer view of Aqueduct Bridge, with Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in foreground (1861-65)

During the Civil War, the water was drained and the bridge modified to allow for horse-drawn wagons and people to walk across the bridge. After the war ended, the superstructure of the Aqueduct Bridge was replaced with wooden Howe trusses and a platform was added on top. That made the structure a double-decked bridge, with boats below and wagons crossing the river on top.

after the Civil War, Howe trusses with a platform on top allowed both boats and horse-drawn wagons to cross on the Aqueduct Bridge

Source: DC Public Library Commons, Aqueduct Bridge

The Alexandria Canal operated between 1843-1886. A brick culvert was built underneath it at Rosslyn, allowing the ferry road to reach the causeway to Mason's Island. That culvert survived until demolition by the Virginia Department of Highways in the 1950's.

the eastern end of the Alexandria Canal had locks that raised/lowered boats to match the level of the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of the District of Columbia and a portion of Virginia (1884)

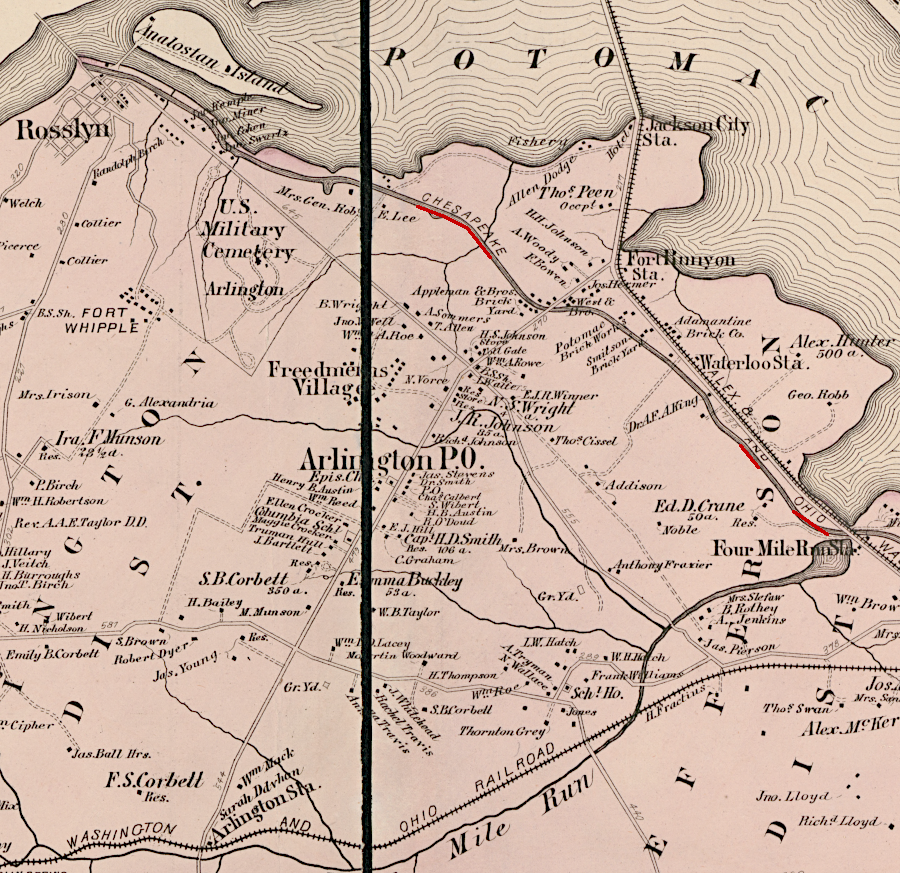

the canal ended up competing with multiple railroads that connected Alexandria to the Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington (by G. M. Hopkins, 1878)

by 1878, the Alexandria Canal running from Aqueduct Bridge to Alexandria had been consolidated with the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington (by G. M. Hopkins, 1878)

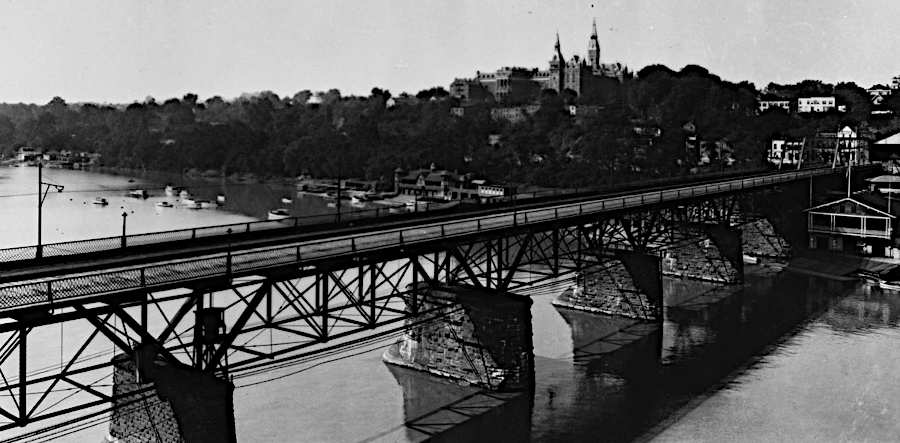

The Federal government purchased the bridge because the private owners were unable to repair it sufficiently. The wooden superstructure was replaced and the bridge opened in 1886 with iron trusses. The Federal government's modifications ended the opportunity for boats to cross the bridge. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal continued to operate into Georgetown until 1924, when flood damage was too expensive to justify repairs. After the 1936 floods, the National Park Service purchased the canal and converted it into public parkland and a hiking/biking trail.

The Great Falls and Old Dominion Railroad widened the Aqueduct Bridge in order to construct its trolley line from Georgetown to Rosslyn in 1903. That trolley line was extended to Great Falls in 1906.

between 1886-1923, iron trusses supported traffic on the Federally-owned Aqueduct Bridge

Source: Wikipedia, Aqueduct Bridge (Potomac River)

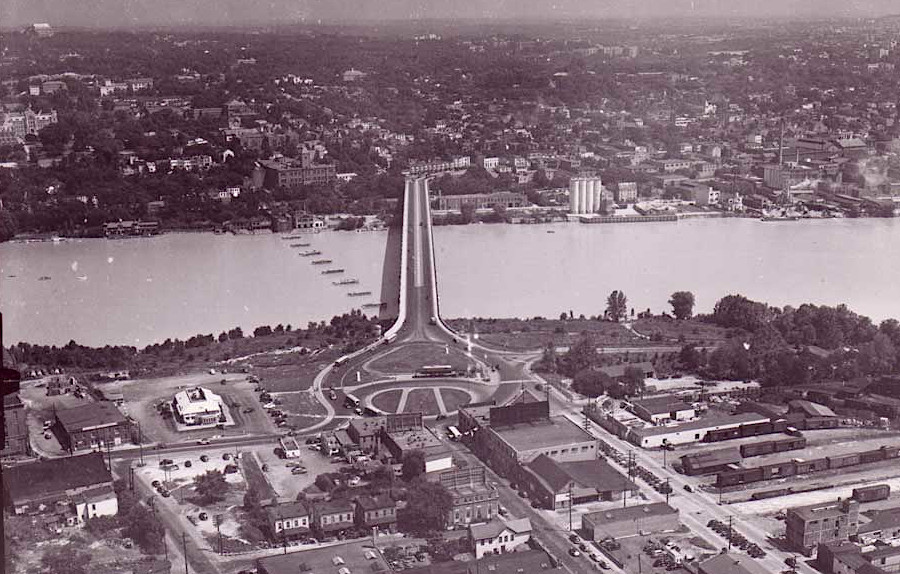

The Aqueduct Bridge was closed to all traffic in 1923 when the new Key Bridge opened. The old bridge's superstructure was removed in 1933 by the Civil Works Administration during the Great Depression, but the Georgetown abutment was left intact. The bases of the eight piers were left in the river to protect Key Bridge from ice, but boaters complained that the remnants were a navigation hazard.

Seven of the eight piers were blasted away in 1962. The last pier next to the Virginia shoreline was retained as an historical artifact. Like the other piers, it rests on a foundation excavated 17 feet deep through the muddy river bottom to reach bedrock.3

the eight piers of the Aqueduct Bridge were left intact until 1962, when seven were blasted away to remove obstructions to navigation

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation (DDPT), Rosslyn, Virginia (c. 1945)

the base of one of the Aqueduct Bridge piers is still visible

Source: Library of Congress, Remains of Pier #1 - Potomac Aqueduct (1967)

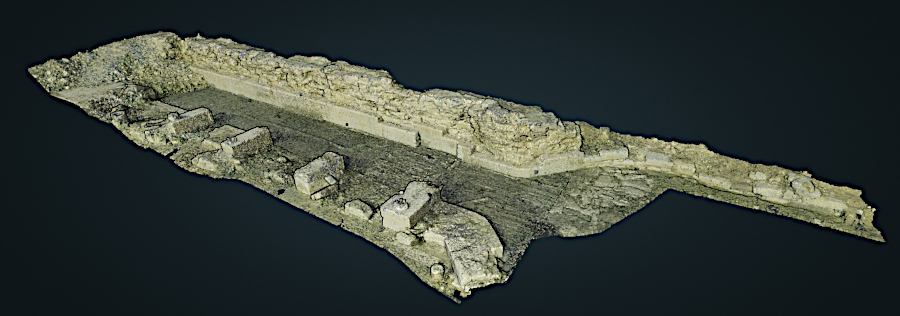

One of the tidewater locks in Alexandria, where the C&O canal packet boats were raised or lowered into the Potomac River, has been reconstructed as an amenity for modern office buildings. In late 2024, archeologists preparing to redevelopment at 425 Montgomery Street excavated the fourth lock and third basin before construction of a parking garage required destruction of the remnants. The stone walls were disassembled and stockpiled for later reconstruction in Montgomery Park.4

the fourth lock and third basin were excavated in 2024-2025, and the stone walls were stockpiled for later reconstruction in Montgomery Park

Source: City of Alexandria, Revealing Sections of the Alexandria Canal

the tidewater lock of the Alexandria Canal has been excavated and restored

Source: City of Alexandria, Revealing Sections of the Alexandria Canal

the Alexandria Canal brought coal, wheat, and other commodities from west of the Blue Ridge, and enabled Alexandria merchants to ship manufactured goods to customers living far up the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the town of Alexandria, D.C. with the environs: exhibiting the outlet of the Alexandria Canal, the shipping channel, wharves, Hunting Cr. &c.

reconstructed tidewater lock for Alexandria Canal (2002 aerial view)

Source: GIS Spatial Data Server at Radford University