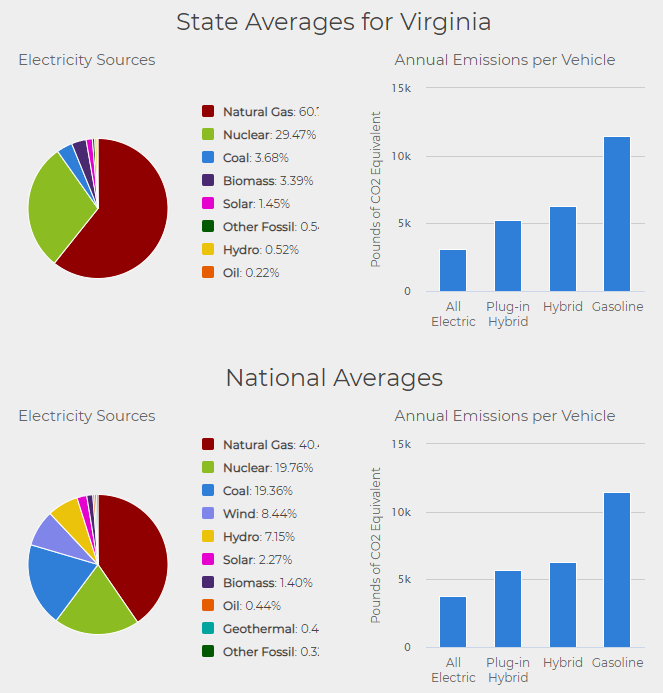

Electric Vehicles (EVs) still generate greenhouse gas emissions, since the electricity they use is not carbon-free

Source: US Department of Energy, Emissions from Hybrid and Plug-In Electric Vehicles

Electric Vehicles (EVs) still generate greenhouse gas emissions, since the electricity they use is not carbon-free

Source: US Department of Energy, Emissions from Hybrid and Plug-In Electric Vehicles

Powering vehicles by electricity was an early concept. William Morrison designed a vehicle based on electricity in 1891.1

In 2020, almost all of the over 400,000 cars and trucks sold annually in Virginia were gasoline-fueled and diesel-fueled internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs). These included hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs). They recaptured some energy during regenerative braking, where rotating wheels turned the motor and created electricity stored in the battery. In basic hybrid vehicles, that battery could not be recharged with electricity from an external source.

Those vehicles were in competition with plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs, also known as Extended Range Electric Vehicles or EREVs) and all-electric vehicles (EVs, also known as Battery Electric Vehicles or BEVs). As a group, PHEV's and EV's were also known as Plug-In Electric Vehicles (PEVs) Those batteries could be charged up by connecting to the electrical grid for as little as 20 minutes or as long as 10 hours.

In 2020, electric cars were only 2% of the new car market. However, one-third of Virginians were considering purchase of a PHEV or EV as their next vehicle, and another 28% were considering some form of electric vehicle for a future car purchase. Consultants warned:2

Calculating the life-cycle costs of a car includes estimating both initial purchase costs and annual operating costs for fuel and repairs, to determine total costs of ownership. In the early 2020's, traditional vehicles fueled by gasoline/diesel typically had a lower initial purchase price, even when governments provided special subsidies and tax benefits. Annual operating costs were significantly lower for vehicles which used electricity, either partially or completely, but the demand for gas-fueled cars will continue.

By 2050 there could be just as many cars fueled by gasoline/diesel on the road as there were in 2020. There will be more cars in total due to population growth, but electric cars will be a higher percentage of the fleet. Even after manufacturers stop making cars using gasoline/diesel, it will take 10-20 years for all the old cars using fossil fuels to wear out unless there is a government buy-out of "clunkers."3

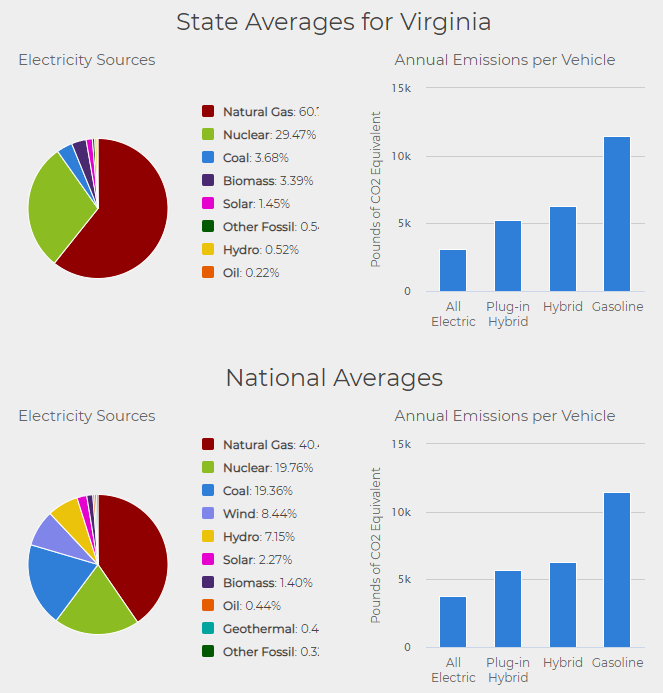

Buyers also had to consider the distance of their trips when choosing what type of vehicle to purchase. An EV with a 100-mile to 200-mile range was adequate for most trips, and hybrids with 25-mile range could avoid using the gasoline engine for many trips. However, in 2023 someone taking long-distance trips in a fully-electric vehicle had to pay close attention to finding charging stations before exhausting the battery charge.

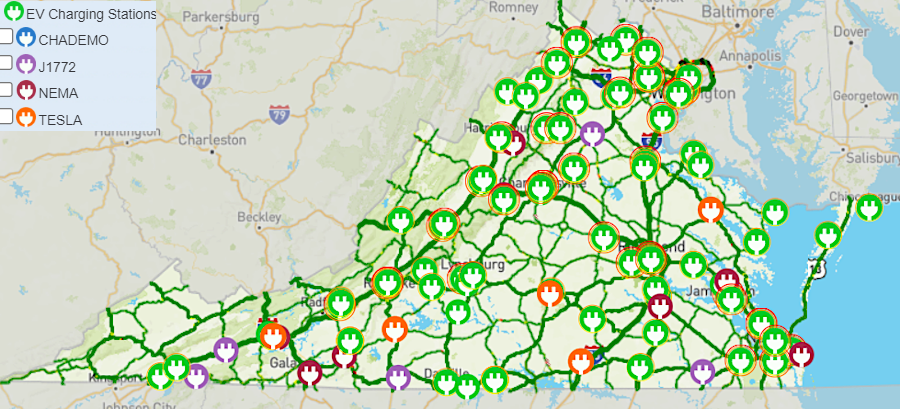

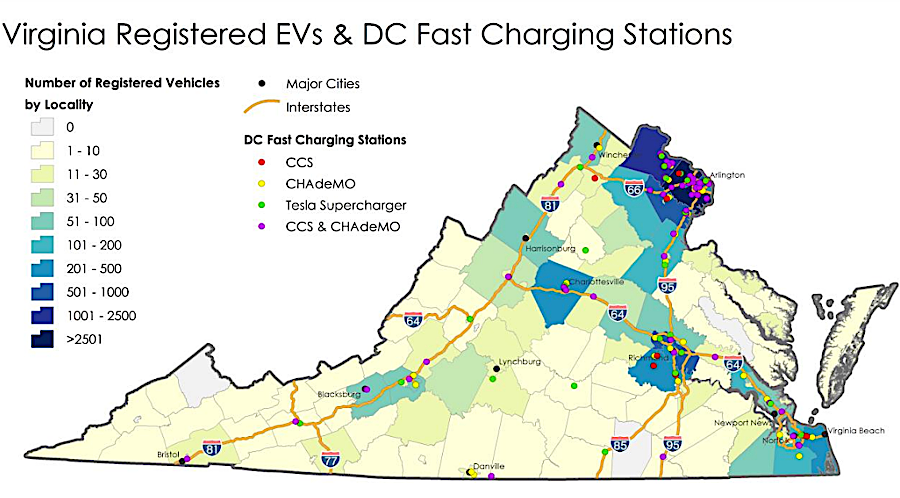

a 2021 study revealed that availability of Combined Charging System (CCS) stations would limit travel even on interstates

Source: Commonwealth Transportation Board, Electric Vehicle

Readiness Study

By the 1930's, the network of refueling stations for cars burning gasoline/diesel was ubiquitous. Drivers of EVs could plug into any outlet offering 120 volt alternating-current, so even an extension cord from a standard house outlet could serve as a Level 1 recharge station. However, EV charging stations offering a fast recharge (within 20 minutes) were far less common in the mid-2020's.

In 2020, powering up a battery for an EV to recover full driving distance site at a Level 1 station required 8-12 hours. That created no issue for workers commuting to a job within 40-50 miles; they could recharge the EV at home overnight. A slow recharge was no issue for drivers with a destination within the range of one charge, and the driver was staying overnight at the destination. Linking to a 120-volt outlet at a hotel or friend's house was relatively simple.

Level 2 recharge station uses a 240-volt recharge from a dedicated 40 amp circuit, with a standard cord attachment. A typical EV can be fully recharged in 6-8 hours at a Level 2 station, so they are suitable in parking garages used by people commuting to work.

gas stations allocated most space for refueling with petroleum products in 2020 - but by 2040, electric recharge stations may no longer be on the sidelines

A Level 3 recharge station relies upon a 480V, direct-current (DC) connection to provide most of a recharge in just 30 minutes. Level 3 recharge stations are most popular at interstate highway rest stops, where travelers are in a hurry to get back on the road.

The different models of the earliest EV's used different cord attachments, complicating the ability of charging stations to service all customers. Tesla created a unique Supercharger based on the North American Charging Standard (NACS). It brought a depleted battery to an 80% charge in just 40 minutes at a Level 3 recharge station. Other automobile companies used the Combined Charging System (CCS) standard, and initially their cars could not use the Tesla Superchargers.

In 2023, competitors moved towards adoption of a common standard. Ford and General Motors agreed to incorporate the Tesla standard into future cars, and Tesla agreed to make its 7,500 Superchargers available to cars manufactured by other companies. Expanding and simplifying how customers could recharge an EV obviously increased the potential to sell more of those cars.4

Potential buyers of Plug-In Electric Vehicles (PEVs) in Virginia anticipated recharging most often at home. Nonetheless, people driving cars with a range of 250 miles still desired the ability to plug in at grocery stores, restaurants, shopping malls and warehouse clubs, recreational areas such as parks, and at entertainment locations such as movie theaters.

For longer trips, there was a need to establish a network of charging stations to relieve the "range anxiety" of running out of battery power before finding a place to recharge. Gas stations such as Wawa installed chargers, but discovered that selling electricity was not profitable.

Drivers at high-speed recharging stations created peaks in demand. Residential customers receive a bill from the utility company which varies primarily as the amount of electricity used increases or decreases. However, the utility company's price for commercial customers includes a "demand charge" as part of the bill. The utility had to build extra generating capacity to meet periods of peak demand. The cost of that extra infrastructure is passed along to commercial customers based on the peaks amounts of electricity used, in addition to the total amount used.

The spikes in utility bills from EV recharging left Wawa and others struggling to price recharging services at a rate which would allow recovery of all costs and making a profit as well. However, getting customers to stay in the store for 20 minutes did offer a number of opportunities to sell other products and services.

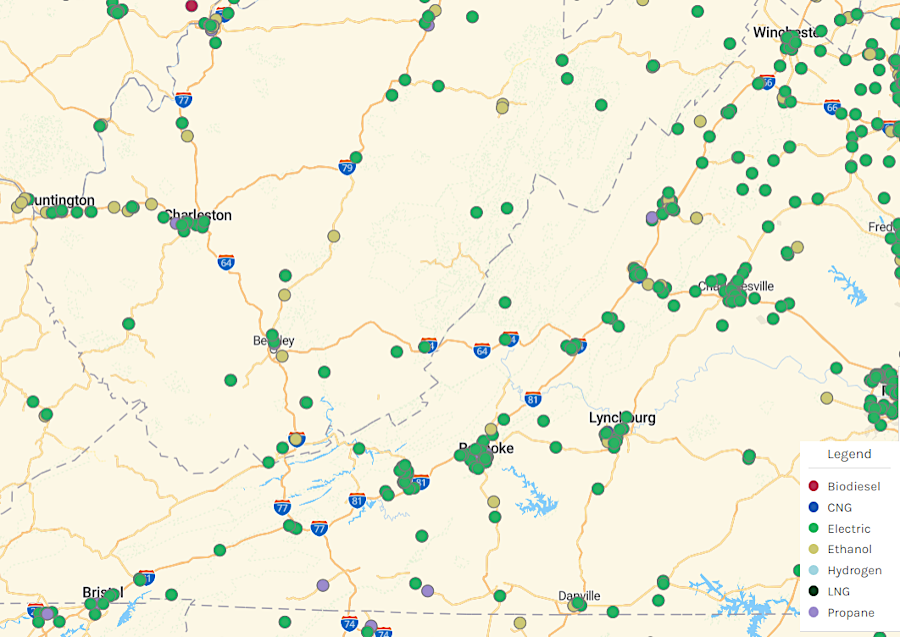

Expansion of the EV charging network was enhanced after the US Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021. Nationwide, it provided $7.5 billion to fund a network of 500,000 EV chargers, of which 75% had to be located in "alternative fuel corridors." Under the 2016 Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act, the US Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration corridors in Virginia included:5

I-95: From Washington DC to Petersburg, VA

I-64 from VA Beach to WV border

I-66: From Strasburg to Washington, DC

I-81: From MD border to TN border

I-85: From Petersburg to VA/NC border

The Federal Highway Administration approved Virginia's Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Deployment Plan in 2022. That qualified the state for $100 million in National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) funding for creating publicly-accessible electric charging stations, along with refueling infrastructure for hydrogen, propane and natural gas vehicles. By 2023, the alternative fuel corridors in Virginia had expanded to include 985 miles on:6

I-64

I-66

I-77

I-81

I-85

I-95

I-295

I-495

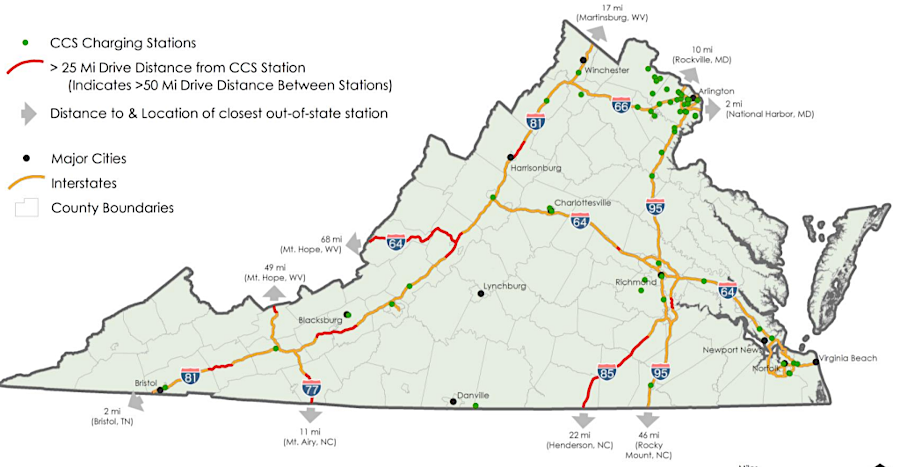

by 2023, 985 miles of interstate highway in Virginia had been designated as "alternative fuel corridors"

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Electric Vehicle

Readiness Study

Range anxiety issues were also addressed in 2023 when seven major automakers committed $1 billion to build a network of 30,000 charging ports across the United States and Canada. At the time, there were just 36,000 fast chargers in those two countries, with places offering a fast charge often separated by hundreds of miles. Ford, General Motors and the other auto companies promised to provide ports for cars using either Tesla's North American Charging Standard (NACS) or the Combined Charging System (CCS) standard.

To make it profitable to build a charging station, it needs to have customers "pumping electrons" for 15% of each day on average. Despite a temporary slump in the sake of electric vehicles, by 2024 chargers were being used 18% of the time. Restaurants and gas stations were adding them, and funding from the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program was expected to speed up the pace of construction of new chargers.

In July, 2024, Bloomberg reported:7

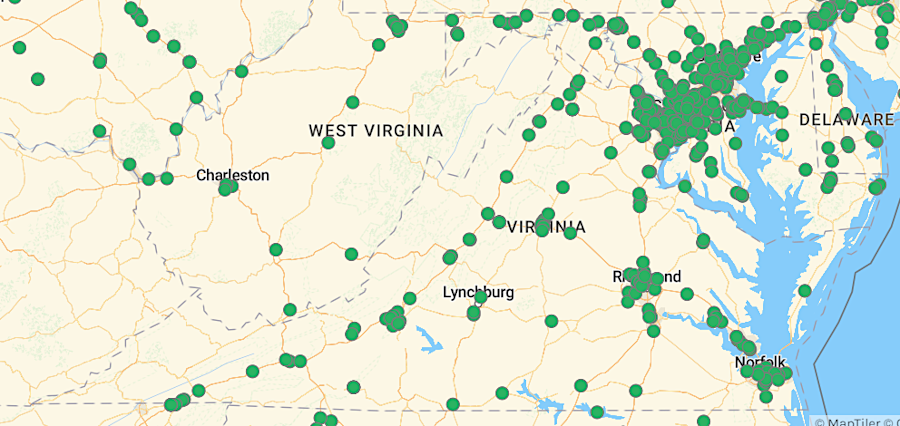

fast charging (Level 3) stations in Virginia in 2023

Source: US Department of Energy, Alternative Fuels Data Center

By 2024 the electrical grid in Virginia was stressed by demand for more electricity to power data centers. The new facilities required new generation capacity and new transmission infrastructure to transport the power to the data centers.

The demand from electric cars would be far less challenging to meet. Dominion Energy projected that in 2028, the peak demand from electric vehicles would be only 1,600 megawatts. Rate subsidies for charging at off-peak hours, especially overnight at home, was anticipated to minimize peak demand.

Virginia was impacted directly when California announced a ban on selling gasoline-only vehicles starting in 2035. After the deadline, at least 80% of car sales must be electric and 20% may be hybrid gas/electric.

The Virginia General Assembly in 2021 had adopted California's vehicle emissions standards and electric car sales targets, using a provision in the Clean Air Act allowing states to accept either Federal standards or California's stricter standards. There was no option in the Federal law to establish Virginia-only standards.

Major car manufacturers had already committed to a fuels transformation. Honda set a 2040 date, and Toyota set a 2050 date, to stop making gasoline-only or diesel-only vehicles.

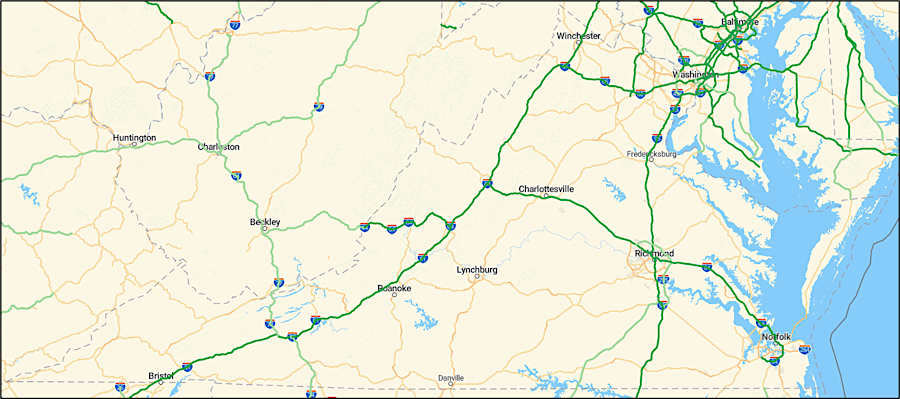

the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) 511 website identifies the location of different types of EV charging stations

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Virginia Traffic Information

American and European manufacturers announced tighter timelines. Ford declared it would end production of gasoline-only or diesel-only vehicles after 2040, and to stop sales of such cars in "leading markets" in 2035. General Motors planned to switch its manufacturing in 2035. Volvo, which makes trucks in Pulaski County, set a 2030 target for making just electric cars. Volkswagen was the most aggressive in making the switch, ending production of gasoline-based vehicles in 2026.

The Virginia Auto Dealers Association supported adoption of the California Air Resource Board standards. Manufacturers of electric vehicles prioritized shipment of those cars to states which had adopted California's standards, and the dealers wanted more vehicles shipped to Virginia for sale to customers. While over 99.9% of Virginia cars still used gasoline or diesel in 2022, the future market was already clear.8

Volvo began to manufacture its Class 8 VNR Electric heavy-duty truck at its Pulaski County plant in 2022. The truck's 264-kWh lithium-ion batteries required only 70 minutes to get to an 80% charge, enabling trips of 150 miles. The development of an electric truck helped ensure Volvo would keep expanding the 2.3 million-square-foot facility, which employed over 3,000 people.

Camrett Logistics, which provided warehousing and distribution services, used an electric truck that it purchased from Volvo to transports items on I-81 to the Volvo Trucks North America plant located in Dublin. The shipments involved trips no more than 10 miles away from the Camrett Logistics warehouses. A 90-minute nightly recharge was supplemented with a mid-day recharge, and the truck was in service 20 hours per day.

At the time, it cost $800,000 to purchase a Class 8 (heavy) electric truck compared to $150,000 for a diesel equivalent. Gas stations selling diesel were readily available, while Camrett Logistics had to spend up to $75,000 to install an electric recharging station. The use of an electric truck was an experiment; the fuel savings alone would not justify the investment.

By 2024, Volvo advertised that the 565kWh available from six batteries in the VNR Electric's 6x4 model provided a 275-mile range, and could get an 80% charge in 90 minutes. The Department of Energy awarded the company a $208 million grant to upgrade the manufacturing of VNR Electric trucks in Pulaski County; the Mack LR Electric model in Macungie, Pennsylvania; and batteries in Hagerstown, Maryland.9

Volvo manufactures its heavy duty Class 8 VNR Electric truck in a 2.3 million-square-foot factory near Dublin (Pulaski County)

Source: Volvo, The Volvo VNR Electric; SRI, ArcGIS Online

For cars, the initial high cost of an electric vehicle were offset by the lower costs to fuel the vehicle. At the end of 2023, when gasoline cost around $3.00/gallon, the equivalent cost to charge an electric vehicle at a residence in Virginia was $1.83 per gallon.10

The Federal push to incentivize production of electric vehicles slackened in the runup to the 2024 presidential campaign. Joe Biden recognized the need to win Michigan, and wanted the endorsement of the United Auto Workers. The union was unhappy that auto manufacturers were planning to build electric vehicles in factories located in right-to-work states when union membership was constrained. In addition, electric vehicles required fewer workers to build.

In a bid to win union support in 2024, the Biden administration reconsidered regulations proposed in 2023 by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to force automakers to shift away from making vehicles powered by fossil fuels. Biden had committed previously to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50% by 2030 and eliminating emissions by 2050. If the rules were finalized, 67% of passenger cars and 25% of trucks sold in 2032 would have to be zero-emission vehicles. In 2023, less than 8% of cars sold were all-electric.

The 2023 draft regulations set a more ambitious target than the previous Biden administration goal for 50% of new vehicle sales in 2030 to be all-electric. The 2024 change proposed by the administration would postpone the requirement to increase sales of zero-emission vehicles, so the biggest increase would occur after 2023 . That would allow the automakers time to develop better cars and transform factories, and protect existing union jobs longer.11

The delay would also provide more time to build more electric vehicle chargers. Sales of electric vehicles had not met projections, in part due to high interest rates for financing new cars but also because consumers had range anxiety. A gas-powered or plug-in hybrid car could refuel at 3,500 gas stations in Virginia, and less than 1,500 places with electric chargers. On a cold day an electric vehicle might drain its battery before reaching a charging station.12

in 2022, charging stations were available all along I-81

Source: US Department of Energy, Alternative Fuels Data Center

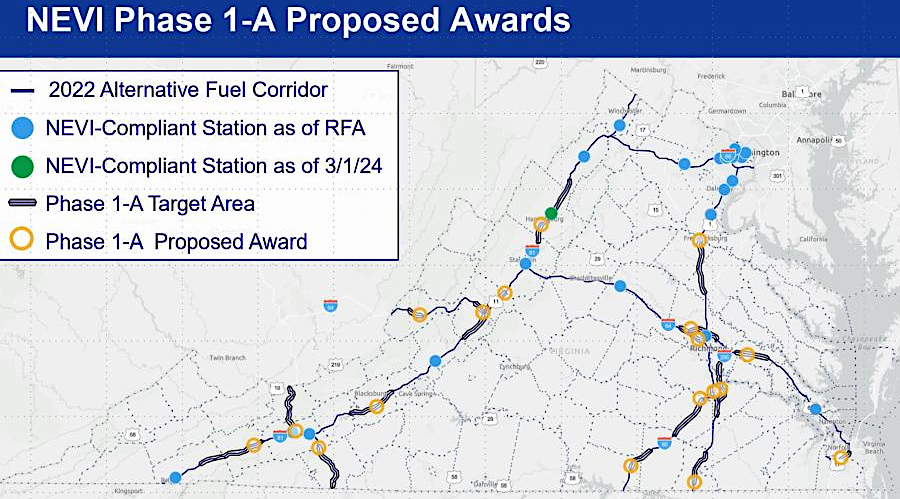

In 2024, the Phase 1-A round of National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) grants provided $11 million to fund fast chargers at 18 different sites, chosen from 128 proposed locations. They were within one mile of interstates, 50 miles away from the nearest planned charger, and developers had to provide at least a 20% funding match.

The Commonwealth Transportation Board anticipated $106 million in National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) grants over five years. By 2024, Pennington Gap in Lee County had installed three electric vehicle chargers in a town of just 1,600 people and demonstrating that rural areas would also support electric vehicles. The town manager said:13

18 fast charging stations along interstates were funded with National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) grants in 2024

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Virginia Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Deployment

electric vehicles are not a new concept - this one was recharging in 1919

Source: Library of Congress, Electric auto at re-charging station

in 2021, most owners of electric vehicles lived in the mos urbanized areas plus the City of Charlottesville/Albermarle County

Source: Commonwealth Transportation Board, Electric Vehicle

Readiness Study