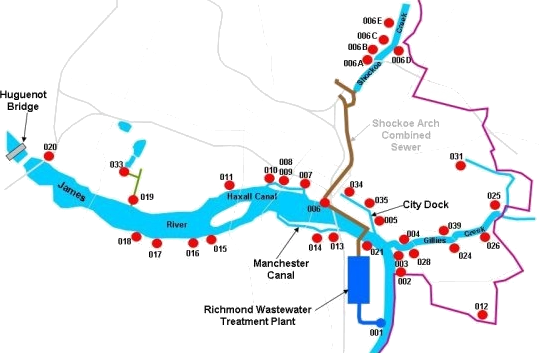

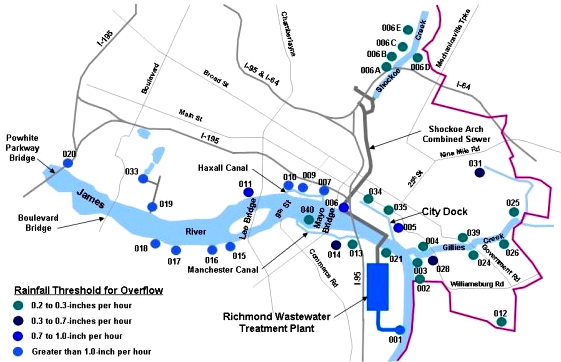

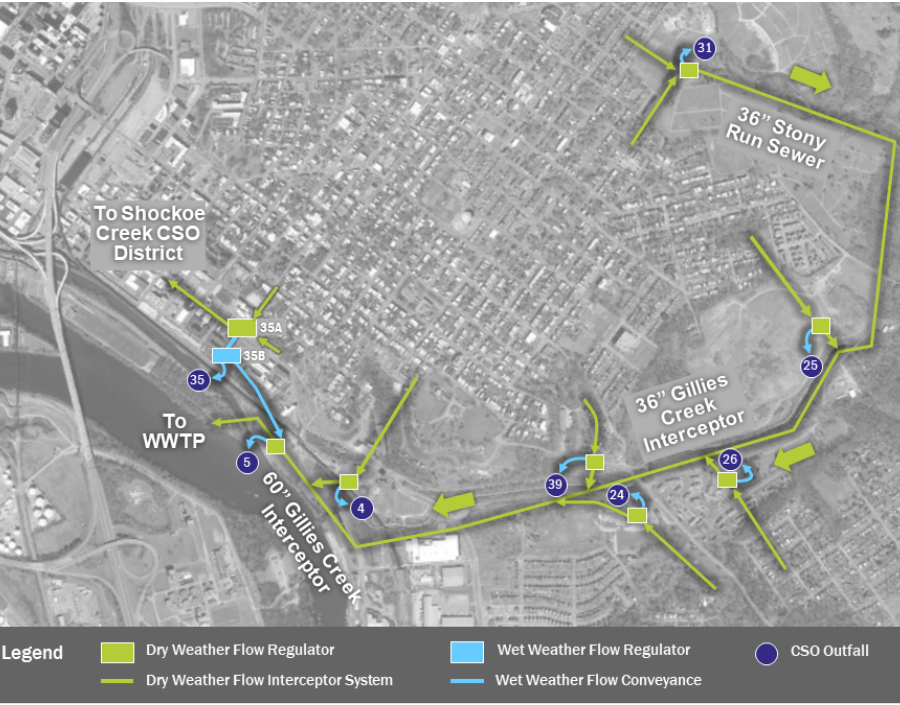

Richmond's sewer system included 31 overflow outfalls along the James River

Source: City of Richmond, Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Project

Richmond's sewer system included 31 overflow outfalls along the James River

Source: City of Richmond, Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Project

Richmond was one of the first cities in Virginia to create a system to carry sewage away from the urban center. The city covered Shockoe Creek and converted the natural drainage in Shockoe Bottom into two underground systems, a 17-foot by 12-foot concrete sewer known as the Shockoe Box and a pressure conduit known as the Shockoe Arch. Sewage was dumped, untreated, in the James River.

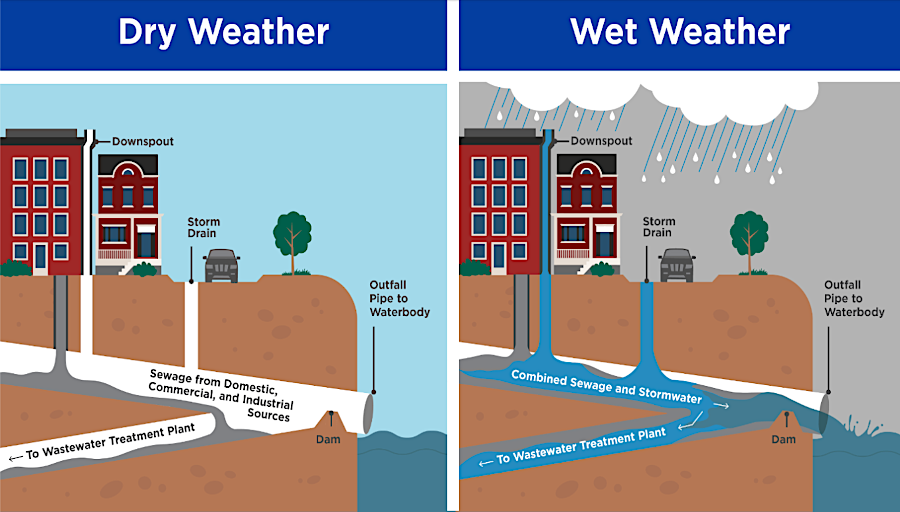

As the urban center was paved, raindrops no longer soaked into the soil. A system of stormwater pipes and ditches was added to divert rainwater away from basements and yards and into local creeks.

In central Richmond, stormwater pipes were connected to the sanitary sewer pipes. Combining them was perceived as a smart way to flush waste faster away from the densely populated areas. There was minimal concern about impacts of what was being dumped into the James River. "Out of sight, out of mind" removal and dilution were the solution to pollution. Natural processes were expected to deal with the surge of bacteria flushed into the river, but it is not clear than city officials cared about that issue at first.

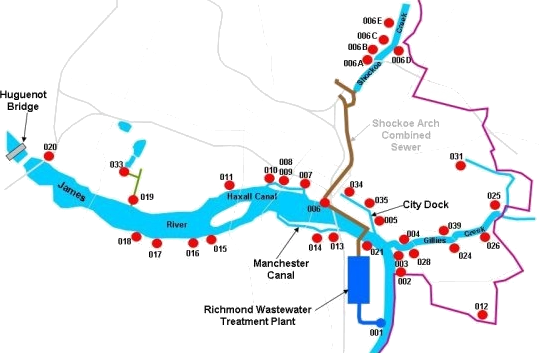

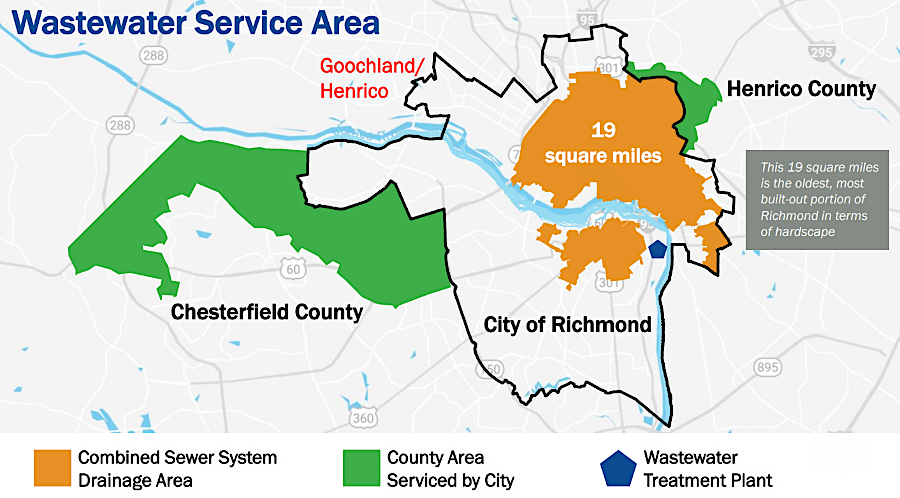

In two-thirds of the expanding city, the pipes and channels carrying stormwater to the river were built separately from the sanitary sewer lines carrying human waste. When heavy rains overloaded the separate stormwater system, floodwaters were polluted with litter from parking lots and silt from excavation sites - but not from human waste. In most of the city, that waste was isolated in separate sewer pipes.

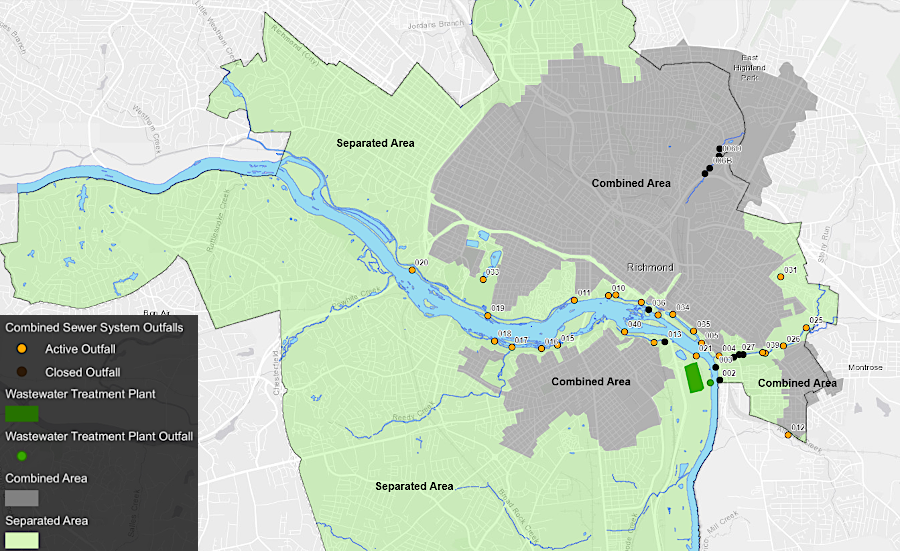

Richmond built its wastewater treatment plant in 1958 and located it on the southern bank of the river, near the Port of Richmond. The city built a 96-inch Shockoe Creek Interceptor pipe to gather waste/stormwater from the north bank, plus twin 66-inch pipes to carry that polluted water underneath the river from the downstream edge of Chapel Island (near Great Shiplock Park) to the wastewater treatment plant on the opposite side of the river. Richmond ended up with 12,000 acres draining into a combined sanitary/stormwater pipe system, the largest Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) area in Virginia.

Until 1958, every time it rained the sewage flowing into the James River was untreated. In the center of the city rainstorms served the function of clearing out the sewer lines.

After 1958, sewage in Richmond was piped to a wastewater treatment plant and processed there before being discharged into the James River. The treatment removed solids and killed bacteria. Treated waste discharged into the James River initially had high levels of nitrogen and phosphorous, but in 1958 the excessive levels of nutrients were not recognized as pollution.

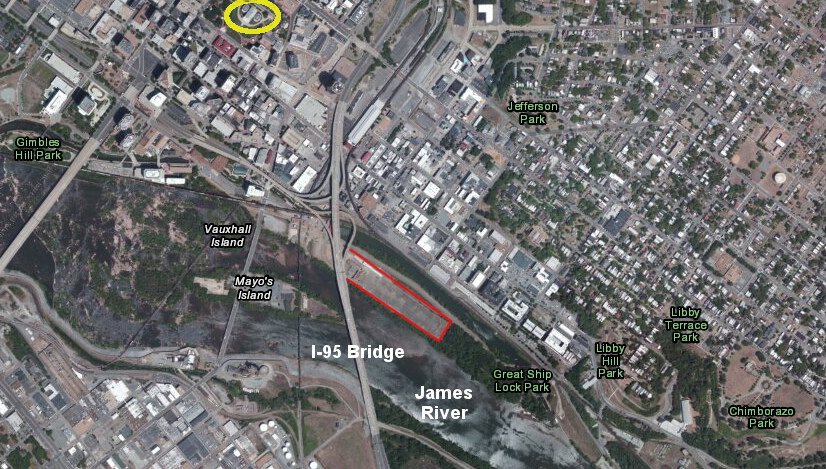

The capacity of the wastewater treatment plant to process "clean" rainwater as well as "dirty" sewage was limited. During a rainstorm, the runoff from impervious surfaces (such as roads and rooftops) would drain into the combined stormwater/sewer pipes and overload the facility. Pipes would fill with water, threatening to back up. To prevent a backup from causing toilets and other pipes to overflow into buildings, the city's sewer pipes were designed with outlets (outfalls) that released excess rainwater+sewage directly into the waterways. The wastewater treatment plant was last expanded in 2021, at the cost of $150 million. Capacity increased from 75 to 140 million gallons a day.

Richmond's Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) ended up with 31 overflow outfalls along the James River or its tributaries, especially Shockoe Creek and Gillies Creek. About two-thirds of the city's total CSO Area is in the Shockoe Basin drainage.

By the start of the 21st Century, the James River Park and boat trips through downtown Richmond were key features of living in the city - but one third of Richmond had a consolidated sanitary/stormwater system that regularly polluted the river. Like Lynchburg and Alexandria, Richmond had retrofitted some of its older pipes to separate sanitary and stormwater pipes. The costs and disruptions caused by construction in the downtown area to separate pipes to reduce the amount of untreated waste discharged through outfalls into the James River during rainstorms limited the benefits of that solution.

in two-thirds of Richmond, sewage and stormwater are mixed in a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) system

Source: Richmond Department of Public Utilities, Richmond's Combined Sewer System

The alternative approach was to expand the capacity of the pipes carrying combined sanitary and stormwater flows to the wastewater treatment plant. Extra storage allowed holding back the peak flows of sewage/stormwater until the treatment plant had room in its tanks for processing the surge.

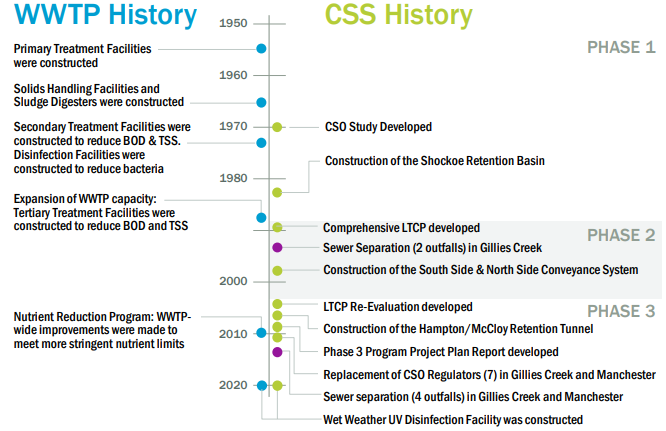

In 1972, the city began planning to construct a retention basin. In 1983, the city built the Shockoe Retention Basin on Chapel Island, just downstream from the former mouth of Shockoe Creek. It was designed to capture 35 million gallons of the initial surge or "first flush" of stormwater runoff from a rainstorm.

Richmond's primary solution in its Long Term Control Plan (LTCP), which was completed in 1988, was to build a massive storage system to capture the surge of stormwater/sewage in pipes and artificial underground lakes. After the storm subsided and flows dropped to normal dry weather conditions, the stored stormwater/sewage was allowed to flow to the treatment plant.

Two underground tunnels were excavated in the Petersburg granite. The hard granite minimized the amount of groundwater that would infiltrate into the tunnels when they were empty, and blocked the wastewater from leaking out when the tunnels were full.

In addition to the 50 million gallon Shockoe Retention Basin, the Hampton-McCloy Tunnel with a 7 million gallon capacity was completed in 2003. The expanded pipes stored an additional 15 million gallons, for a total of 57 million gallons.

At the beginning of a storm, the initial stormwater runoff contained the greatest amount of contaminants that had accumulated since the last storm. Capturing the dog waste, oil and grease from automobiles, and litter in the "first flush" had the greatest environmental benefit.

If the rainfall exceeds the capacity of the Shockoe Retention Basin, then combined sewer overflow (typically 90% rainwater, 10% sewage) poured into the James River. Heavy storms still exceeded the storage capacity of the Shockoe Retention Basin and Hampton-McCloy Tunnel, but the combined sewage/waste released through outfall gates caried a lighter load of pollutants.

The Shockoe Retention Basin and pipes leading to can be filled with 50 million gallons in less than 30 minutes during a large rainstorm. The captured flow then drains over four days, released as the wastewater treatment plan has capacity for processing.

However, remnants of Tropical Storm Gaston dropped 11 inches of rain on Richmond on August 30, 2004. All the underground pipes filled within three hours, including the "Arch." That main drain was 17' high and 29' wide. Shockoe Bottom flooded, in part because one outlet gate was rusted shut and the Dock Street Pumping Station lost power. The floodwall, designed to prevent the James River from overflowing into Shockoe Bottom, ended up preventing the combined stormwater and human waste from flowing into the river.

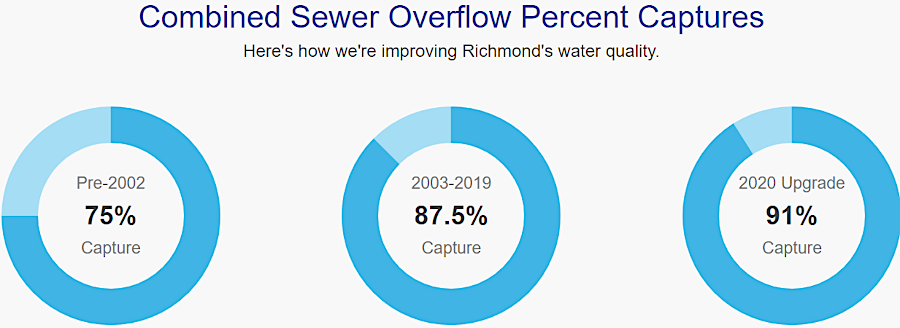

Before completion of projects in the Long Term Control Plan, Richmond was treating only 62% of the total volume in the combined sewers. When the other 38% flowed directly into local streams and the James River, raw sewage waste was diluted with stormwater but the smell was clearly evident. That obviously limited recreational activity on the riverfront, and affected the potential benefits of the city's "Main to James" redevelopment plan.1

Shockoe Retention Basin on Chapel Island (red outline) is on the north bank of the James River, not far from the State Capitol (yellow circle)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Shockoe Retention Basin included an aeration system intended to keep solids in suspension until the storage was emptied. By 2008, however, a 10-foot thick layer of sewage had settled on the bottom, similar to the solids that accumulate on the bottom of a septic tank.

The city had not designed a clean-out option when it built the retention basin in 1983. Richmond had to spend over $12 million to build a ramp down to one wall of the Shockoe Retention Basin, cut a hole in the wall, and use backhoes to remove the solidified sewage.2

rainfall required for discharge from 29 different overflow outfalls in Richmond (before construction of the Hampton McCloy Tunnel)

Source: Richmond Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Water Conditions

Storing that initial runoff helped the city avoid overwhelming the wastewater treatment plant with too much inflow. Some Richmond CSO outfalls discharged sewage less than once/year on average, but others regularly poured a mixture of water and untreated waste into the James River.

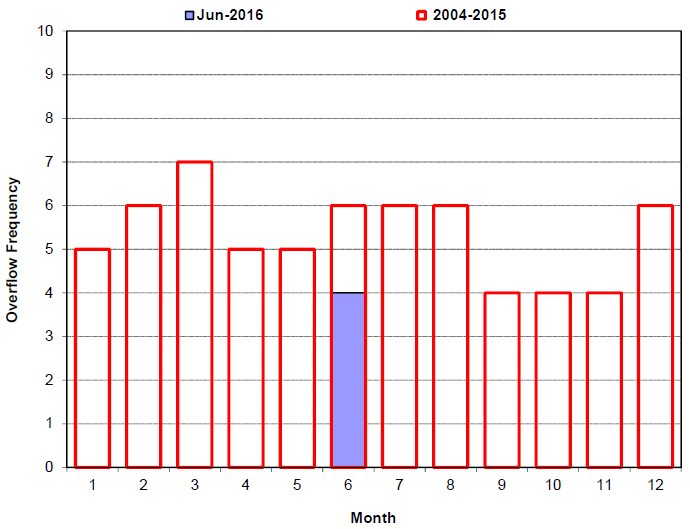

CSO6, one of 29 overflow outfalls in Richmond, has a pattern of discharging polluted water at least four times in every month of the year

Source: Richmond Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Monthly Reports (June 2016)

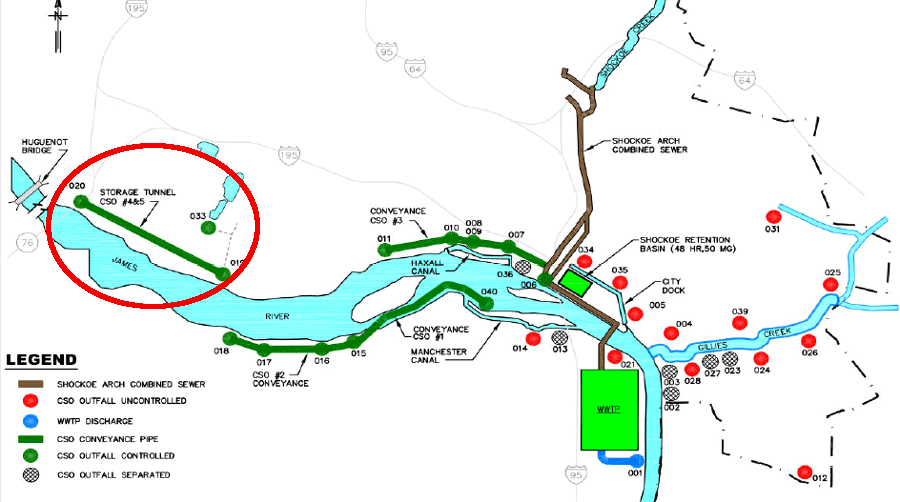

To stop discharges from two CSO outlets upstream from the river rapids that attract a great deal of recreational use, the city built a $50 million, 600-foot long, 14-feet wide underground tunnel between Hampton and McCloy streets (the Hampton McCloy Tunnel) in 2003.

The city located the underground storage for 7 million gallons in Petersburg granite, to minimize the amount of infiltration. Engineers designed the tunnel so water from the James River and Kanawha Canal could be used to flush out the solids. The tunnel was carved out of the bedrock 70 feet below the sewer line, so special engineering was required to dissipate the energy of the water as it dropped into the tunnel.3

Source: City of Richmond, 2018 Combined Sewer System Video

The underground retention basin and Hampton McCloy Tunnel could trap 60 million gallons of combined sewage and stormwater, but a 10-minute rainstorm can completely fill up the underground storage. Richmond still discharged untreated waste each year, and bacteria levels in the James River exceeded state standards for half the weekends in the summer of 2016.

The capture-store-treat approach would require additional projects, additional funding, and additional years of construction. As one Richmond official noted:4

the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) and the Combined Sewer System (CSS) were built in stages

Source: City of Richmond, CSO Interim Plan Report (p.1-6)

Eliminating the discharges from overflow outfalls on the western side of the city resulted in cleaner water for recreational use downstream in James City Park, especially for popular rafting/kayaking activity at the Fall Line. However, cleaning up the pollution in the West End of Richmond exposed city officials to charges of environmental prejudice. The city's population on its western side is wealthier and includes less minorities.

the Hampton McCloy Tunnel stretches from McCloy Street near I-195 to Hampton Street east of Maymont Park, and red dots in the East End indicate where untreated sewage is still released as of 2016

Source: Richmond Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Project Overflow Points

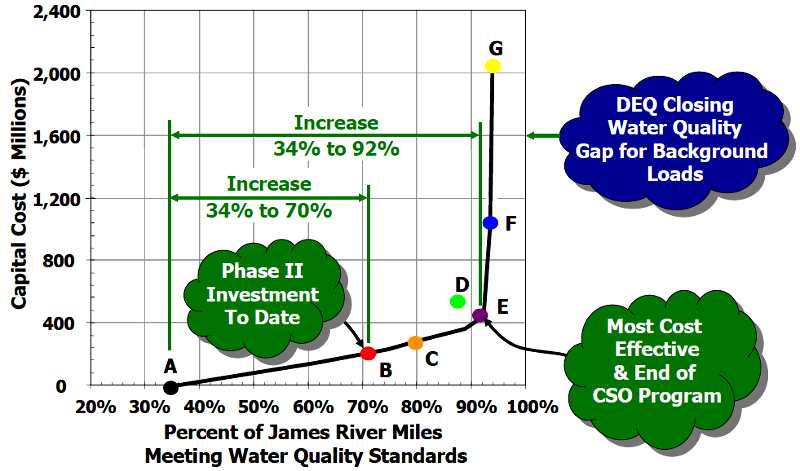

EPA conducted a "knee-of-the-curve" economic analysis to define a point where increased clean-up expenses in a Long Term Control Plan would no longer be matched by a reasonable set of increased environmental benefits. For its Combined Sewer Overflow project, Richmond proposed to reach compliance with Clean Water Act standards for 92% of the James River.

Using EPA's willingness to consider costs as well as benefits, Richmond told to the State Water Control Board and EPA that the costs to implement 100% of the possible clean-up actions would fully exceed the benefits.

economic analysis indicates a point ("knee of curve") where incremental costs to reduce pollution increase dramatically after 92% of the James River miles comply with water quality standards

Source: State Water Control Board, City of Richmond Reasonable Grounds documentation

Richmond's proposed solution for avoiding the costs of the remaining 8% includes reclassifying Gillies Creek through a Use Attainability Analysis. Reclassification would exempt the city from reducing pollution enough to permit recreational use. Reclassifying the creek would eliminate recreational use as an objective would lower the threshold for clean-up.

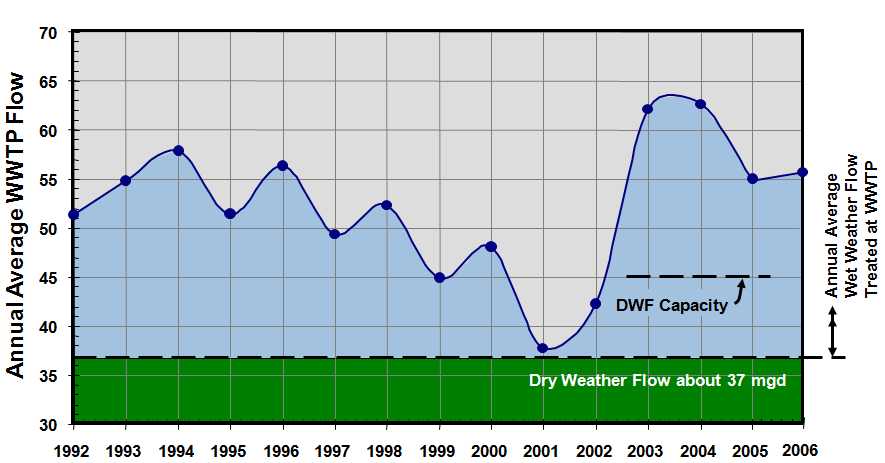

after Richmond's wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) reaches its maximum inflow, the excess water/waste is discharged directly to the James River and its tributaries through different overflow outfalls

Source: Robert Steidel, Accommodating CSO Flows/Loadings in the Chesapeake Bay Nutrient TMDL (Wet Weather Partnership 2010 Workshop Presentation)

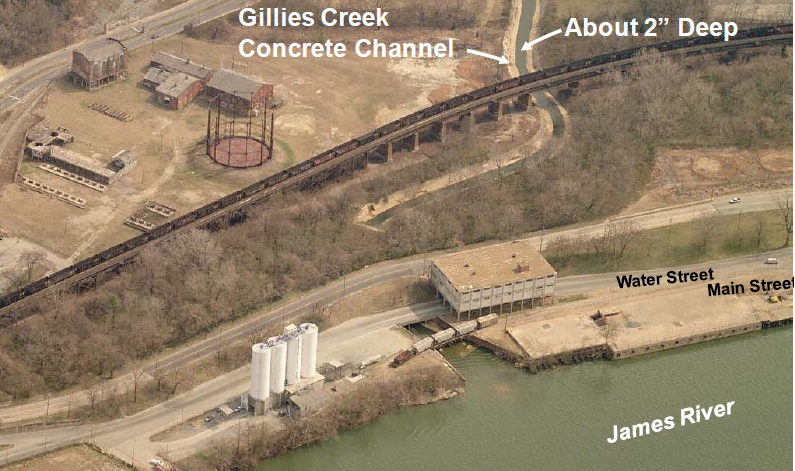

From where the creek enters the city to its confluence with the James River near the old Fulton Gas Works, the natural channel of Gillies Creek was replaced with concrete in 1974. Paving the creek reduced flooding and sediment erosion, but did not reduce the excessive levels of bacteria that contaminate the water.

The city claimed it would have to spend $300 million to construct a 30-million gallon storage tunnel to capture stormwater and divert it to the wastewater treatment plant. The city also noted that Gillies Creek:5

Richmond's proposal for a Use Attainability Analysis notes that Gillies Creek has a normal flow of water only 2" deep except in rainstorms, offering little opportunity for swimming or wading, so Primary Contact Recreation is not currently an existing use

Source: State Water Control Board, City of Richmond Reasonable Grounds documentation

In 2011, the State Water Control Board rejected the city's request to conduct a Use Attainability Analysis. The city could conduct its own study, but the state agency did not want to appear to endorse a solution that would not require any reduction in the pollution levels.6

Five years later, the city viewed Gilles Creek more as an asset rather than as an open sewer. The Gillies Creek Greenway was proposed, to create a pedestrian/biking corridor as part of revitalization in the East End. At the James River, the greenway would connect to the Virginia Capital Trail near the new Stone Brewing Company development at the former Intermediate Terminal. The other end would be anchored at the former Armstrong High School, in a low-income area of the city.7

Richmond chose to reduce CSO overflows on the West End first, and delayed cleaning up Gillies Creek on the East End

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality required Richmond in 1985 to develop and implement a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) control program. Consent Orders have been issued and revised several times since then.

The 2005 consent special order from the State Water Control Board allowed continued discharges while Richmond implemented the 2002 Long Term Control Plan (LTCP). Recognizing the massive cost involved, the state's order failed to define when the city had to eliminate the overflows into the James River. In 2018, over three billion gallons of untreated sewage/stormwater were released.

In 2020, the General Assembly set a deadline for Richmond to minimize discharge of untreated waste by 2035. Alexandria and Lynchburg were required to finish by 2027; Richmond was granted extra time because of the greater scope of the challenge.

The state legislature required Richmond officials to produce an interim plan to address discharge by 2021 and a final plan by 2025. The city initially estimated the cost to be around $500 million.8

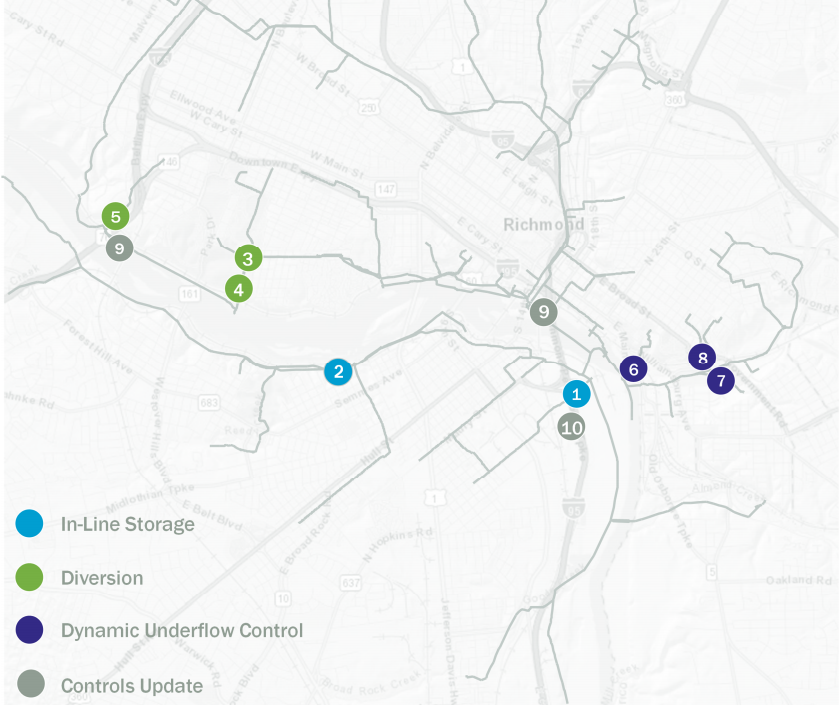

The interim plan produced in 2021 examined 18 possible projects, and recommended spending $33 million to complete 10 of them first. When the interim plan was drafted, there were five projects required by the 2005 Consent Order which had still not been completed. Two of them were replaced by interim plan projects. Completion of the remaining three was delayed because of their relatively low cost-effectiveness for reducing E. coli bacteria in the receiving waters.9

the 2021 CSO Interim Plan Report recommended 10 projects

Source: City of Richmond, CSO Interim Plan Report (July 1, 2021)

the 2021 CSO Interim Plan Report recommended projects to divert additional flow to the Hollywood Interceptor and away from the CSO 3 Pipeline

Source: City of Richmond, CSO Interim Plan Report (July 1, 2021)

the 2021 CSO Interim Plan Report recommended three Dynamic Underflow Control projects to divert additional wet weather flow to the Gillies Creek Interceptor

Source: City of Richmond, CSO Interim Plan Report (July 1, 2021)

After the US Congress passed the American Rescue Plan in 2021 to stimulate the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic, Richmond requested $30 million to fund the 10 projects in the interim plan and $833 million to fund all the projects that were expected to be proposed in the 2025 final plan. Richmond had already spent over $300 million, so the total cost to eliminate overflows was projected at greater than $1 billion.

Combined with requests from Alexandria and Lynchburg, the state sought $1.4 billion for Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) upgrades. If customers of the utility ("ratepayers") in Richmond were required to finance $833 million for the city's projects, rates were projected to triple from $700 to $2,200 per year. One of the members of the State Senate, a key sponsor for passage of the 2020 legislation setting the 2035 deadline, commented about the $833 million cost estimate:10

Governor Northam allocated $50 million to Richmond, which the city matched with another $50 million. The Governor also included another $100 million in fis FY22 budget proposal, which the city also committed to match. While far short of the $833 million needed to complete the project, that total would fully fund the projects in the interim plan.

When the interim plan projects were completed in 2027, the city expected to capture 91% of the overflows. To intercept 99% of the overflows was projected to cost roughly $800 million more. Finding that additional $800 million was a difficult challenge for Richmond officials.11

In 2020, Richmond's entire general fund budget was $770 million. The ability of Richmond to fund another $833 million in sewage projects by 2035 was questionable. The Environmental Protection Agency had scheduled completion of the Long Term Control Plan for Lynchburg to put a cap on tax increases required to fund the project, but Richmond taxpayers had no such protection in the legislation passed by the General Assembly.

Richmond's mayor made clear, after getting just $50 million from the American Rescue Plan funding, that more assistance would be needed:12

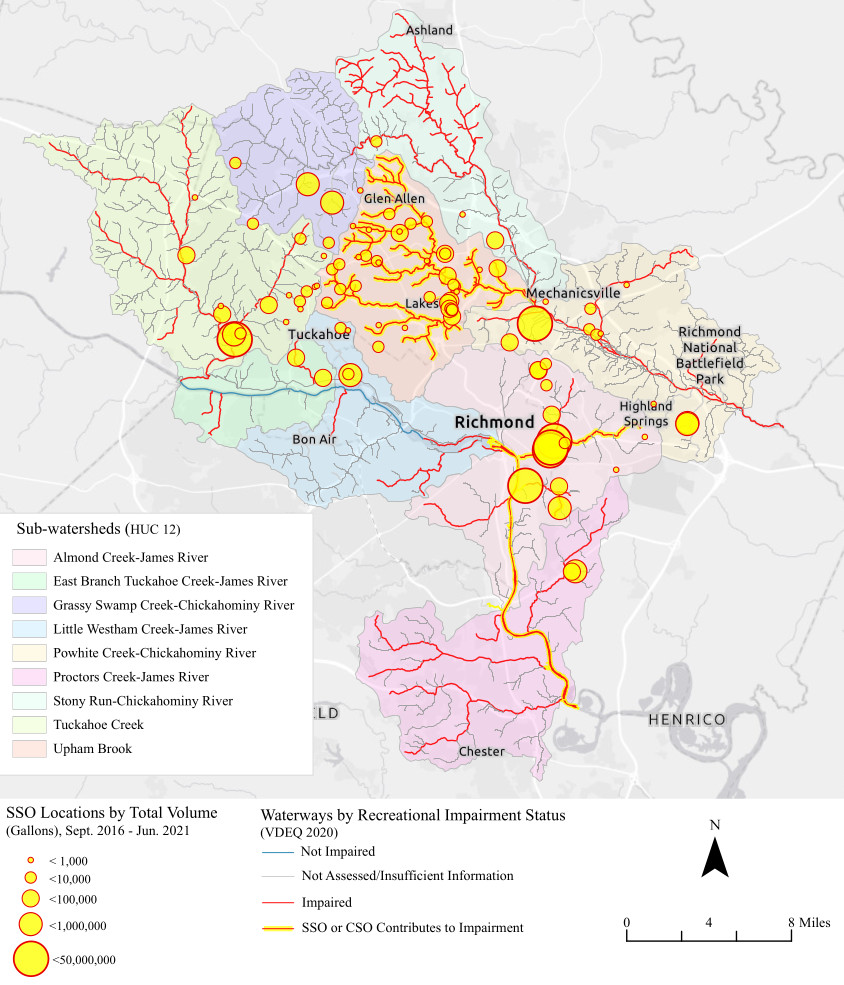

While the General Assembly mandated Richmond reduce its flow of untreated waste into the James River, the State Water Control Board and the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) were more relaxed in dealing with overflows from Henrico County's sanitary sewer system. In 2021 the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, James River Association and Environmental Integrity Project sued the county for failing to fix leaks in its sewer pipes that had allowed 66 million gallons of raw sewage to flow into the James River since 2016. In addition, since 2019 the Henrico County Water Reclamation Facility had violated its state permit 10 times, releasing excessive amounts of sediment.

Sanitary Sewer Overflows (SSO) occur when rainfall infiltrates the sanitary sewer system and overloads the pipe capacity

Source: Environmental Integrity Project, Henrico Photos and Video

The State Water Control Board and the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) response to the problems was to sign yet another consent order with Henrico County, the fifth consent order since 1990. The county also agreed to pay a $200,000 penalty.

Environmental organizations were not satisfied with the state response. They noted that the consent order did not include a plan or deadline for systemic improvements, and complained that the "piecemeal approach" with different consent orders would continue to allow raw swage to escape Henrico County's pipes during times of heavy rainfall. Unlike Richmond, Henrico County had not created a mechanism for notifying the public each time the sanitary sewer system overflowed.

When filing its lawsuit, the Environmental Integrity Project noted:13

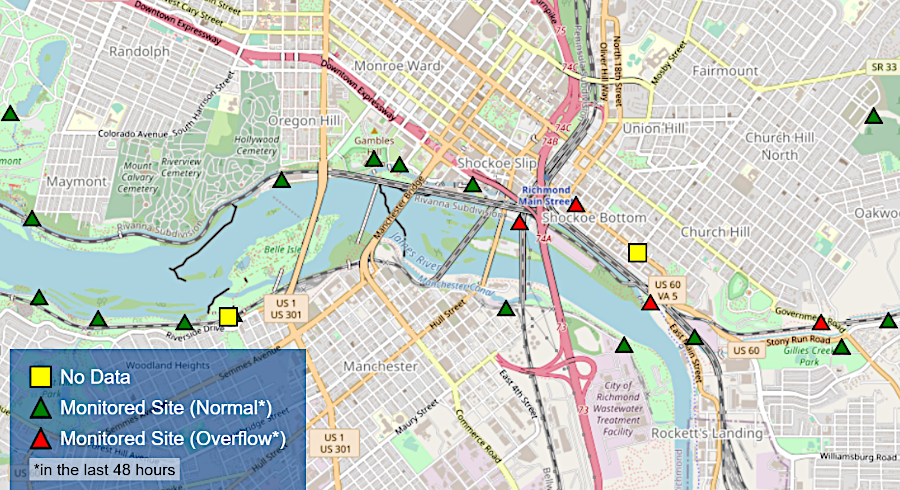

sewer overflows on October 30, 2021 are highlighted in red

Source: RVAH20, Combined Sewer System Overflow Events

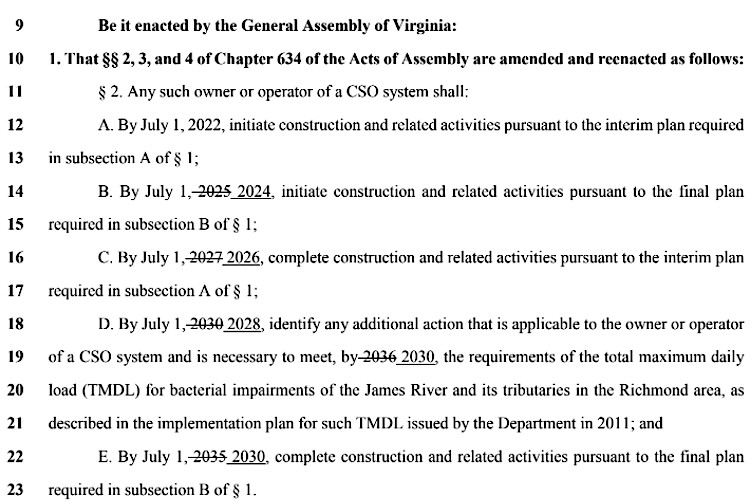

The 2022 General Assembly considered legislation that would require Richmond to accelerate its plan to end overflows by imposing a 2030 deadline, rather than maintain the 2035 deadline imposed by the legislature two years earlier. City officials warned that faster action would require raising wastewater rates paid by customers by 232% to more than $2,500 a year.

Toilets in the Capitol and Executive Mansion send their sewage through the Combined Sewer Overflow system. Pipes 27 feet in diameter in Shockoe Bottom help discharge two billion gallons of sewage/stormwater annually into the James River, almost 10% of the flow in the city system. State Senator Chap Petersen, a Democrat who supported the faster deadline, said:14

"the General Assembly ultimately rejected a proposal in 2022 to accelerate the deadline for eliminating Combined Sewer Overflows in Richmond

Source: Virginia General Assembly, Substitute for SB354 for S-Finance and Appropriations Offered on 2/8/2022 (2022 Session)

One possible source of additional funding was the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, passed by the US Congress in 2021 after the American Rescue Plan. The infrastructure bill included $50 billion for upgrading water and wastewater systems, and prioritized financially distressed communities. About 20% of the ratepayers for sewer service in Richmond were impoverished. Tripling sewer fees from $65 a month to $170/month, in order to raise $800 million more to eliminate wastewater overflows, would impose a major burden on those residents.

Environment Protection Agency Administrator came to Richmond in early 2022. During a tour of the Shockoe Retention Basin, former Richmond mayor and current US Senator Tim Kain said:15

The bill to accelerate the state-imposed timeline, SB354, passed the State Senate on a 36-4 vote in 2022. However, the legislation died in a House of Delegates subcommittee on a 5-4 vote. The proposed deadline was made conditional on the availability of additional Federal/state funding, but the one Republican to join the Democrats in voting against the faster timeline still said:16

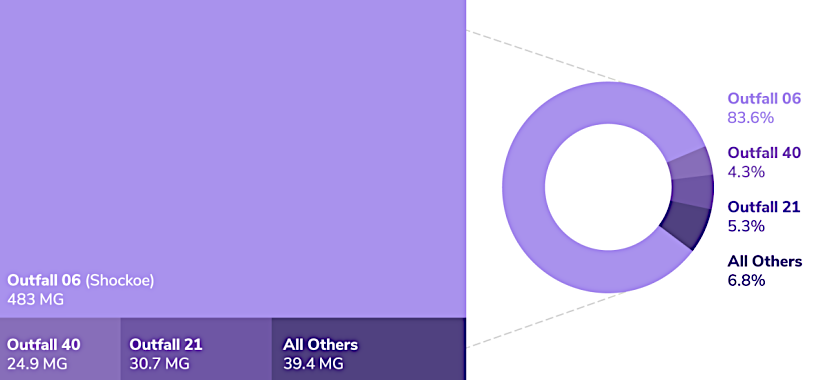

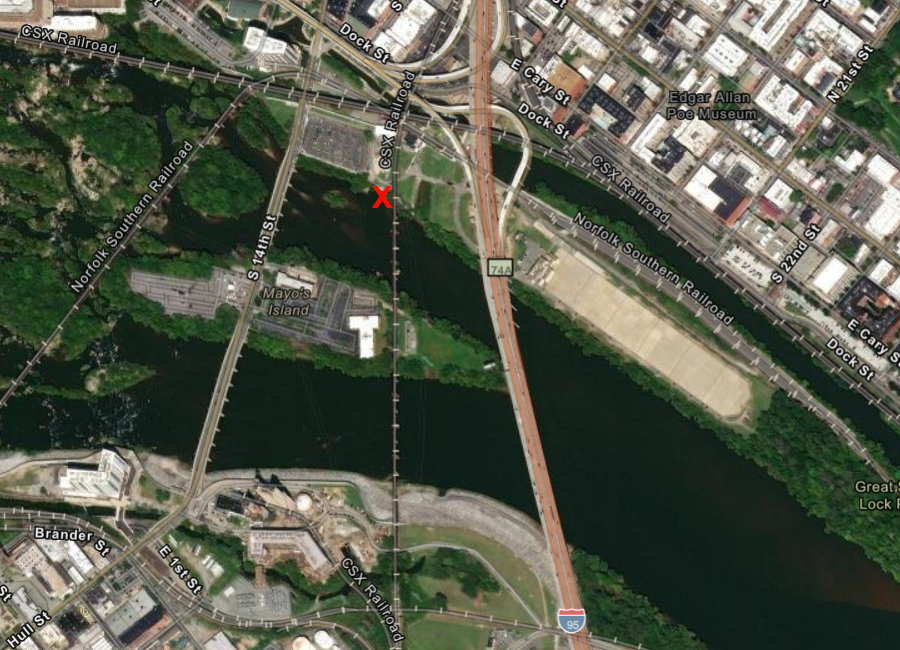

Funding was dedicated to complete multiple small projects by 2027, at which point 92% of the flow would be captured and directed to the wastewater treatment plant. In 2023, city officials projected than an additional $1.3 billion would be required to fund the "Final Plan" to intercept the remainder. The most important project still to be funded was at Outfall No.6 next to the 14th Street Takeout for kayaks/canoes. At that outfall, 80% of the combined wastewater was being released into the river.

after 2027, 80% of the remaining sewage/stormwater outflow will occur at Outfall No.6 (red X)

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Richmond Combined Sewer Overflow Outfall Progress Report (2022) and ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The General Assembly provided an additional $100 million for Richmond's project when it reached a FY2022-2024 budget compromise in May, 2022. An additional $100 million was proposed.

However, the budget amendments with the additional funding were not approved until September 2023. In the final budget there was not an additional $100 million for Richmond, in part because the budget compromise deal took so long to negotiate. The extra $100 million had been proposed for the fiscal year that had already ended on June 30.17

One option to reduce construction costs was take advantage of existing pipes which were no longer being used to capacity after industries had closed. Surges of stormwater could be trapped in those pipes to minimize the need for new underground tunnels. New in-pipe gates could be closed in various places in the sewer system to capture some of the combined sewage flow surge. Gates could be opened to release the wastewater, after a storm had passed and the wastewater treatment plant had processing capacity again. A network of in-sewer sensors and on-the-surface rain gauges helped the city identify that the Gordon Avenue pipe could be used for storage.

In 2023, the city also considered skimming off the most diluted flow that reached the underground Shockoe Basin, building a new structure to treat it with ultraviolet light to kill bacteria, then release that treated water into the James River. Building the equivalent of a mini-treatment plan would be less expensive than building one or more new underground basins to store the surge.18

By 2024, the city was predicting that wastewater rates would have to increase by 160-220% in order to cover the costs, even if they could be reduced to $650 million. City residents averaging 3,000 gallons/month were already paying $51.95/month, compared to $28.36/month statewide. Richmonders using more water per month, such as businesses, were paying nearly twice the statewide average for wastewater fees.

In his proposed FY25-26 biennial budget released in December 2023, Governor Youngkin included a total of $50 million for the Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) project in Richmond. City officials asked state legislators for #$300 million total - $100 million in the "caboose" budget for FY24, $100 million in FY25, and $100 million in FY26.

The 2024 General Assembly initially declined to add the $50 million. The final budget, approved in a special session, did provide $50 million in FY25. That funding came from the FY24 budget surplus, and without legislative action would have been automatically deposited into the Water Quality Improvement Fund. The $50 million was modified in the 2025 General Assembly session and spread across FY25 and FY26, $25 million each.19

Later that year, a pipe carrying combined sewage-stormwater started to leak. It was in a highly-visible location in downtown Richmond, underneath the James River Park Pipeline Walkway on the shoreline below the CSX railroad viaduct. A raft guide floating the James River spotted the leak.

The initial leak released only stormwater, since the upstream end of the pipe was isolated from the sewer system. In July, however, sewage began to leak as well; evidently there was a backup in the pipe further downstream towards the wastewater treatment plant. The same river guide reported it again, and the city finally fixed the leak. The guide had to cut short a commercial raft trip, and said later:20

In 2024 the city obtained approval from the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) to pretreate stormwater flowing into the Shockoe retention basin to kill bacteria, using ultraviolet (UV) light. Bacteria-free water in the basin could be released into the James River before a major storm triggered an inflow of combined sewage and wastewater. With the extra capacity in the retention basin, the flows from a major storm that carry a high percentage of sewage would be captured and later directed to the wastewater treatment plant.

Pre--treating stormwater to kill bacteria, then releasing it to create capacity for "dirtier" combined flows, reduced the estimated cost to reach the 2035 target to eliminate sewage releases into the river. Projected costs between 2025-2035 dropped from $1.3 billion to $650 million. The more-expensive alternatives required constructing more retention basins, or more pipes and pumping stations to retain and direct combined stormwater flows to the treatment plant.21

City residents had already paid 70% of the costs to upgrade the combined sewer overflow system; their monthly bills were double the statewide average. Finding a way to reduce the costs of addressing the potential 772 million gallons that could flow from Outfall 6 at Shockoe Bottom was the primary remaining challenge. Revising the 35 million-gallon Shockoe Retention Basin to allow ultraviolet light to treat some stormwater would allow the city to meet state water quality standards for bacteria.

However, diversion from the wastewater treatment plant would not reduce microplastics or nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous, or allow for future treatment techniques to process PFAS and other pollutants for which the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) might set limits. That was standard for stormwater. No water in the separate stormwater system received treatment, except for sediment that might be captured in stormwater ponds. The combined stormwater/sewer systems in Alexandria, Lynchburg, and Richmond created the potential for cleaning up at least some of the stormwater that was not feasible in other Virginia localities.

The executive director of the James River Association, which promoted conservation of the river, supported the planned approach to use ultraviolet light and focus on bacteria. He said:22

Sanitary Sewer Overflows (SSO) from Henrico County also impair streams

Source: Environmental Integrity Project, Map 1. Sanitary Sewer Overflows and Waterways Impaired by Bacteria

Richmond's 140 million gallons/day (MGD) wastewater treatment plant is large enough to treat normal wastewater flow from Henrico and Chesterfield counties, but peak stormwater runoff can exceed capacity

Source: City of Richmond, DPU’s Plan to Manage the

Combined Sewer System (January 2022)

in 2021, about 10% of the peak flows of combined sewage/stormwater were still flowing untreated into the James River

Source: Richmond Department of Public Utilities, RVAH2O

mixing sewage and stormwater in a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) system can result in untreated waste flowing into nearby streams

Source: Richmond Department of Public Utilities, Richmond's Combined Sewer System