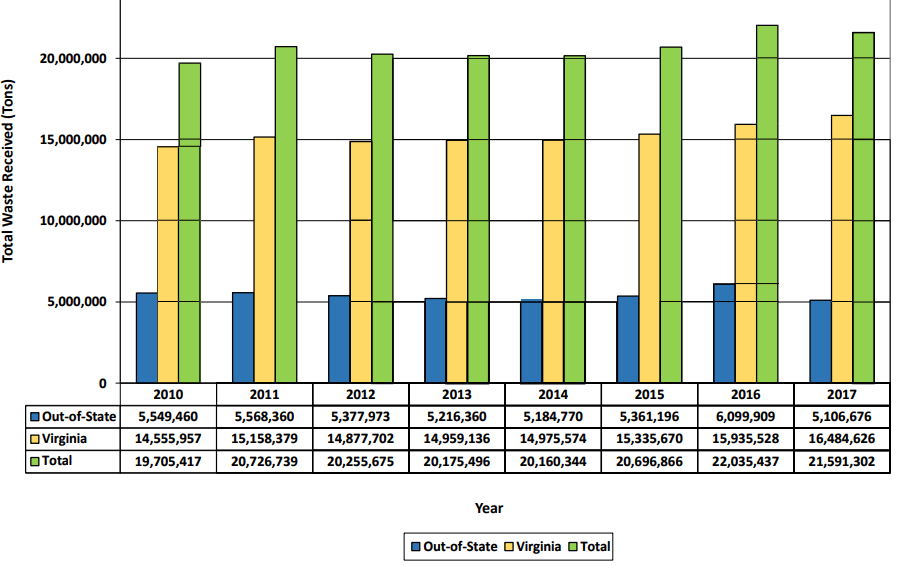

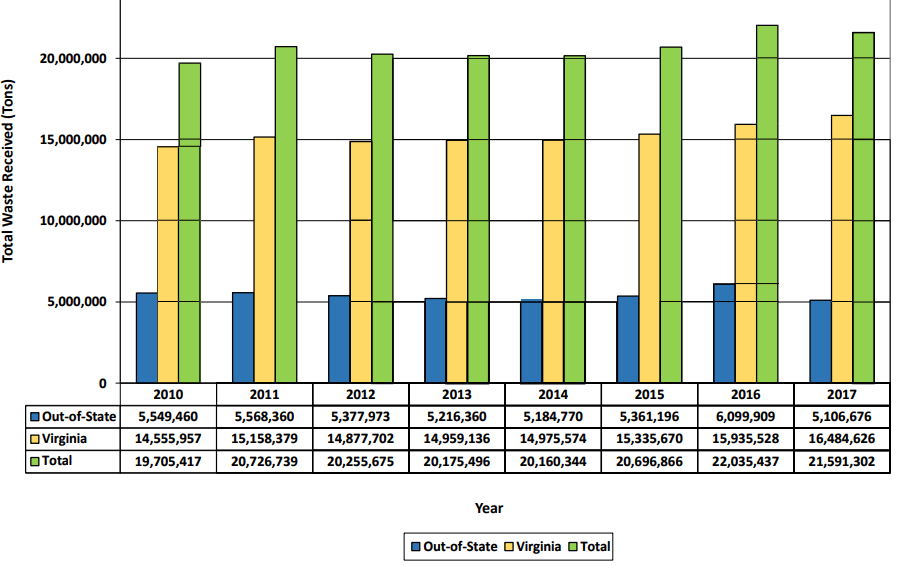

total solid waste received, 2010-2017 (primarily municipal solid waste and construction/demolition/debris)

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2018 Annual Solid Waste Report for CY2017 (Figure 1)

total solid waste received, 2010-2017 (primarily municipal solid waste and construction/demolition/debris)

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2018 Annual Solid Waste Report for CY2017 (Figure 1)

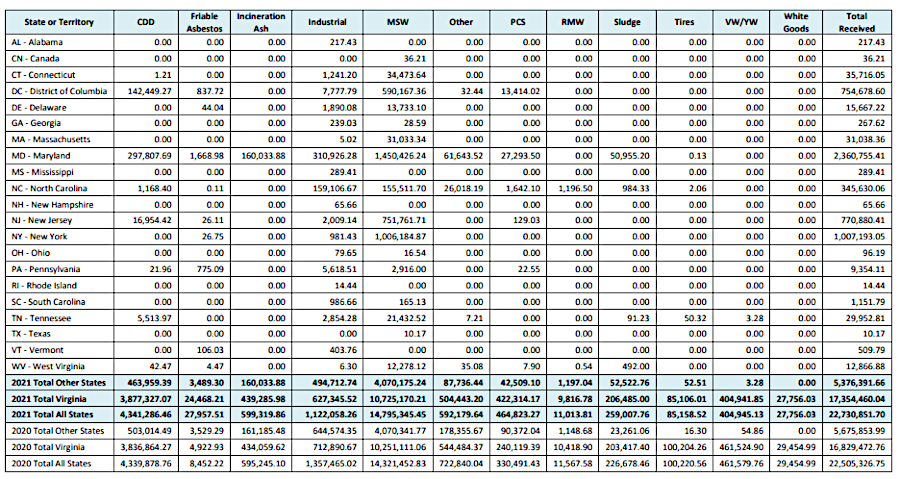

in 2021, Virginia imported waste primarily from Maryland, New York, New Jersey, and the District of Columbia

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2022 Annual Solid Waste Report for CY2021 (Table 2)

Virginia had no state regulations controlling disposal of solid waste until 1971. The Virginia Department of Health took the initial lead in closing open dumps, since they were breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

Since then, the focus on waste management has increased dramatically, and the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality has assumed the lead role for managing solid waste disposal. It has issued regulations for different types of waste, distinguishing hazardous waste (toxic materials), liquid discharges from wastewater treatment plants, construction and demolition debris (C&DD, including discarded lumber, broken chunks of concrete, and stumps from construction sites), and other categories.

Recycling focuses on municipal solid waste (MSW), generated in houses, offices, and stores. Municipal solid waste is described by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as including:1

Solid Waste Disposed in Virginia's Permitted Facilities (2007)

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Waste Reduction Efforts in Virginia (Table 1)

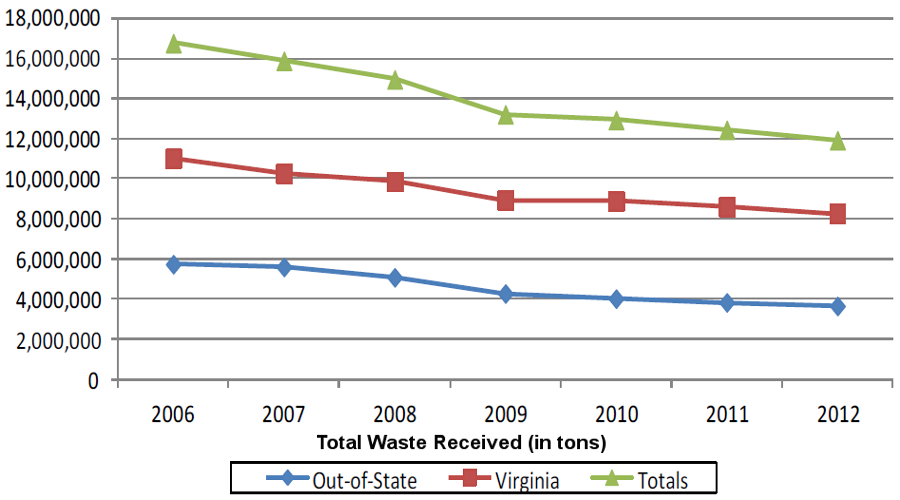

recycling and reduction in packaging materials are reducing the amount of solid waste

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), "Waste Reduction Efforts in Virginia," Solid Waste Managed in Virginia During Calendar Year 2012 (Figure 3)

Municipal solid waste is what we see every day in garbage cans. Extensive education efforts to get people to reduce, reuse, and recycle in order to reduce municipal solid waste have altered waste disposal practices since the 1970's, but recycling is not new in Virginia.

The earliest Virginians salvaged all the possible value from their stone tools before discarding them. When the sharp edge of a rock knife became dull, the Native American flint knappers would chip away at the edge to sharpen it again. If a tool broke, the tool makers would rework it to serve another purpose, until the rock was finally discarded. Thanks to the residues and discarded tools, we have enough evidence of knapping changes over time to speculate on changes in settlement patterns, based on changes in the tool types (such as "Clovis" and "Folsom" points) that we find in archeological sites.

knapping points creates shards of waste rock, and lithic scatters can offer clues to the presence of Native Americans 10,000 years earlier

Source: National Park Service, National Park Service Providing Historic Preservation Support to American Indian Tribes

For perhaps 10,000 years, the "waste" in Virginia was very minimal. Hunting and gathering bands took full advantage of the animals they hunted, using the meat for food, the bones and horns and teeth for tools, the sinews for the equivalent of string and rope, the hide for clothing, and the animal brains for tanning the hides to delay their decay.

There were some discarded items. Large mounds of discarded oyster shells were piled up in middens after the meats were extracted for food. After Native Americans in Virginia adopted agriculture about 3,000 years ago, stable settlements developed where the travelling bands chose to stay in one place for longer periods of time. The Indians used pottery to store their food. Broken pieces of soapstone bowls and shards of pottery crafted in different styles survive in many locations across the state, providing clues to archeologists regarding who lived where.

Native Americans also created agricultural waste from the parts of corn, bean, and squash plants that were not eaten, plus walnut shells and other parts of food that was gathered rather than grown. Modern archeologists now retrieve and identify tiny parts of plants (including pollen grains) and shards of animal bones to determine what people were eating at a particular site prior to the 1600's. In pre-colonial times, "municipal solid waste" (discarded animal and plant material) was 100% organic except for soapstone, pottery and stone points. It quickly decayed in Virginia's climate; oyster middens are the only pre-colonial equivalent to modern landfills.

archeologists use oyster middens to identify where Native Americans were concentrated in the past

Sources: National Park Service, Archeology: Native American and Historic Use of Liberty and Ellis Islands,

National Public Radio, Oyster Archaeology: Ancient Trash Holds Clues To Sustainable Harvesting

European colonists brought a dramatically different culture, and created dramatically different waste patterns. Even before 1607, there were European products circulating in Virginia. Archeologists find glass and metal items in Native American towns that were occupied before Jamestown was settled.

Hernando de Soto camped close to the modern border of North Carolina-Virginia in 1540, and items from his expedition could have been traded north into Virginia. The Spanish who landed on the Middle Peninsula in 1570 brought a variety of alien metal and cloth directly into Virginia. Some ended up being worn as decorative clothing by the Natives after the Europeans were killed, and ultimately all the Spanish items imported in 1570 were discarded somewhere. Other than those two visits, all European goods in pre-1607 locations came from sailors who traded for food and other items along the Atlantic coast during the 1500's.

The English who settled permanently in Virginia came unprepared for the new environment. Excavations at Jamestown show they brought suits of armor, which were unrealistic to wear in the heat of Virginia. From a waste management and archeological perspective, the European culture was far wealthier in worldly goods. The earliest trash pits excavated at Jamestown reflect how pottery, metal, and other items were shipped across the Atlantic Ocean, only to end up very quickly as waste dumped into a hole in the ground - often the bottom of a well.

determining when a location was occupied can be done by dating pottery and other broken items discarded in trash pits

Source: National Park Service, 2011 Public Archaeology Field School

Had the English abandoned Jamestown permanently in 1610 rather than returned after meeting Lord Delaware at the mouth of the James River, their artifacts would be found only in limited areas. As the English settlement of Virginia continued, European cultures supplanted Native American cultures in Virginia. The waste from the colonial period until today has changed, reflecting how technology and cultural preferences have shifted. Some discards are clear time markers, such as lead Minie balls from the Civil War, cellulose acetate filters from cigarettes, and aluminum pop tops from soda cans in the 1960's. Archeologists of the future will be able to document the changing population patterns by excavating landfills and old dumps scattered across the state since 1607.

Agriculture dominated the Virginia economy until the mid-1900's. There are small garbage dumps on farms scattered across the state. Most waste produced on a farm was organic material that would decay quickly, but there are glass bottles and broken pottery in the garbage dumps plus scattered pieces of rusting farm machinery at the edges of old woodlots. Rural families piled up their waste in a convenient corner of each farm, rather than haul it to a community dump. Family graveyards were maintained to look attractive, but dumps were "out of sight, out of mind" locations.

When examined today, dumps reveal household debris (broken crockery and bottles, worn-out utensils, and especially tobacco pipes with different size stems) and farming debris ("tired" tools, metal clips used on harnesses for mules and horses, etc.) Cabins housing enslaved people included items that had once been used in the mansion house but since transferred to the lowest class, plus occasionally some evidence of African culture such as glass beads arranged carefully in special patters for spiritual/mystical reasons and blue paint used to ward off bad spirits.

Since Virginia lacked urban centers until the middle of the Eighteenth Century, most waste pits reflected the lifestyles on individual plantations and their associated quarters or isolated houses on the frontier. The wealth of a household can be measured by waste products. Stratford Hall and Mount Vernon had a different culture and a different waste stream from the farms in the Shenandoah Valley, or the cabins of the enslaved.

In rural Virginia, household waste disposal was easy. Farm families could just dump their debris behind a ridge or in a depression in the pasture away from the farmhouse. For 3,000 years, that is how Native American and then colonial farmers handled waste. Technological innovations in the 1800's, such as tin cans, created more-obvious and longer-lasting waste piles somewhat comparable to oyster middens, but most waste was still organic and decomposed easily.

old farm dump on what is now Manassas National Battlefield Park

Until cars and tractors became common in the 1920's, the most common single item of solid waste in Virginia farms and towns was animal waste. Horses produced manure in the cities, and on the farms cattle created vast quantities of dung. During the Civil War, camps and roads all smelled of excrement produced by horses and mules.

Farmers recognized dung as a valued resource rather than just a waste product. Dung was a fertilizer to spread upon their fields, and George Washington built a "dungery" where his enslaved workers mixed animal waste and discarded plant material to form valued compost.

In Virginia's towns, however, dung was just a waste product. The smell and flies in Virginia's urban centers were distinctive before the internal combustion engine provided a different form of horsepower for transportation, and a different smell from tailpipes.

Modern visitors in Colonial Williamsburg may notice small mounds of manure on Duke of Gloucester Street from the horse drawing carriages, but that waste is minor compared to what would have been present in the 1700's. Even when Williamsburg had less activity between sessions of the General Assembly, there still would have been mounds of fresh horse dung deposited on the streets every day.

During meetings of the House of Burgesses, the town was packed with legislators and assorted other hangers-on, the people who came to town for one of the rare moments of entertainment in the days before movies, radio, TV and the Internet. At those times, horse manure might have covered the streets and added a strong ambience to the scene.

the large number of horses required for artillery units in the Civil War produced large amounts of solid waste

Source: Library of Congress, Richmond, Virginia (vicinity). Major (JM) Robertson's Battery of Horse Artillery

Horse manure faded as a solid waste management problem after the widespread adoption of cars and tractors. Anyone who rides horses today still knows the challenges of "mucking out" the stalls in a barn and replacing the manure-covered straw. In addition, modern gardeners, like George Washington, may collect manure for use as a soil conditioner.

recreated "dungery" at Mount Vernon, where George Washington managed animal manure and compost as a fertilizer resource

Piles of bottles, cans, and waste metal are still common in Virginia woods where farm families once disposed of household waste. Some households still compost their organic kitchen waste, but nearly all solid waste is carried to a regulated landfill or recycling facility now.

As a result of modern pollution control laws, waste disposal even in rural areas of Virginia with a widely-scattered population requires centralized landfill operations. In most rural communities, homeowners carry their waste to a transfer station. These are often green metal boxes, designed to contain liquids and block rats/raccoons/bears from getting into the garbage until a truck hauls the trash to one of the sanitary landfills remaining in Virginia.

transfer station, where household trash is collected and compacted before transfer to sanitary landfill

When population density reaches a certain threshold in urban areas, it makes sense to have a waste disposal service collect garbage from homes and businesses and carry it away. Arlington County reached that threshold at the end of the 1920's. When Arlington implemented curbside collection in 1930, it was so attractive to the residents in the town of East Falls Church they gave up their charter as a town in order to take advantage of that county service.

access to easy recycling reflects urbanized pattern in Virginia - and population density matters

"9 of 10 SWPUs reporting highest recycling rates had population densities greater than 250 persons/square mile, while

6 of 8 SWPUs reported as not meeting mandated rates had densities less than 62 persons/square mile"

SWPU = "Solid Waste Planning Unit" (In 2008, there were 71 SWPU's in Virginia)

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Waste Reduction Efforts

in Virginia (Commission Briefing - September 8, 2008)

2008 recycling rate - Virginia averaged 38.5%, better than the national average of 32.5% of "Principal Recyclable Materials"

(paper, metal, plastic, glass, commingled materials, yard waste, waste wood, textiles, waste tires, used oil, used oil filters,

used antifreeze, inoperative automobiles, batteries, electronics and other)

Top 10/Bottom 10 of the 71 Solid Waste Planning Units (SWPU's) in Virginia in 2008:

the City of Falls Church reported recycling 59.3%, but at the other end of the scale,

the Caroline County SWPU reported recycling just 10.4%.

(Central Virginia Waste Management Authority SWPU includes the counties of Charles City, Chesterfield, Goochland, Hanover, Henrico, New Kent, Powhatan, Prince George

plus the cities of Richmond, Hopewell, Colonial Heights and Petersburg)

(Rappahannock Regional Solid Waste Management Board SWPU includes the county of Stafford plus the city of Fredericksburg)

(Southern Crater Region SWPU includes the counties of Dinwiddie, Greensville, Surry, and Sussex plus the city of Emporia)

(Northern Neck PDC SWPU includes the counties of Lancaster, Northumberland, Richmond and Westmoreland)

(Southside Regional PSA SWPU includes the counties of Charlotte, Halifax and Mecklenburg)

Source: statistics from Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), The Virginia Annual Recycling Rate Report: Calendar Year 2008 Summary

Federal legislation and Federal court decisions have significantly affected the disposal of solid waste in Virginia over the last 40 years. The primary Federal law shaping landfill operations now is the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), with regulations in the Code of Federal Regulations (Section 258 of Title 40 (Protection of the Environment).2

State law, particularly the provisions of the Virginia Waste Management Act, is in the Code of Virginia.3

Changes in the laws, and the interpretations of the laws, have dramatically reshaped the patterns of waste disposal. Solid waste regulations have gotten more restrictive, limiting the locations where waste could be discarded. Updated regulations now require expensive liners to seal the waste into individual "cells," and landfill operators must cover the waste each night with a dirt or fabric cap.

As a result, large operations gained an economic advantage with economy of scale. Small open dumps - usually rat-infested, and often smoldering and occasionally with open flames - were forced out of business.

Small facilities were close to the waste supply, such as the old town dump on Quarry Road near downtown Manassas. The new landfills that comply with the regulations were built further away from population centers, increasing the cost of hauling the waste.

In 2007, Virginia had 195 permitted waste management facilities, including construction and demolition debris "stump dumps," 60 active landfills accepting municipal solid waste, and 11 waste-to-energy incinerators.

Covanta waste-to-energy facility at Lorton, in Fairfax County (2018)

Source: Historic Prince William, #73

According to the DEQ statistics, 23 million tons of solid waste were processed in 2007. The landfills accepted 15.9 million tons of municipal solid waste, of which 5.6 million tons was imported from out of state.

2007 waste disposal statistics for Virginia

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Waste Reduction Efforts

in Virginia (Commission Briefing - September 8, 2008)

Constructing and operating a landfill is a big business. According to a state report:4

installation of landfill liner for new cell at Prince William County landfill

Source: Prince William County, Quarterly Project Report – Fiscal Year 2021, Fourth Quarter

Attempts to limit out-of-state imports of solid waste were blocked by a Supreme Court ruling that the interstate transport of solid waste business is interstate commerce, and states may not impose special limits or taxes on garbage hauled across state lines. The US Constitution requires that all states must treat commerce in garbage the same way they treat commerce in soybeans, coffee cups, computers, etc.

A statewide "tipping fee surcharge" (a tax on all waste, whether produced inside Virginia or hauled into the state) would be constitutional. However, Governor Gilmore vetoed a bill to impose a tipping fee in 1999, and the General Assembly refused to pass another bill in 2002.

EPA has a national goal of 35% recycling rate. (Recycling rate is the total tonnage of recycling, divided by the total tonnage of solid waste collected.) Virginia now exceeds that level, though the state's minimum standards are significantly lower. Virginia has two recycling standards: a 25% standard for recycling municipal solid waste, except for communities with population densities less than 100 persons per square mile or with an unemployment rate 50% higher than the statewide average. Those communities are only required to recycle 15% of the municipal solid waste generated within their boundaries.

2006 recycling rates in Virginia

Source: The Economic Benefits of Recycling in Virginia, Figure 11

In 2007, only eight Solid Waste Planning Units (SWPU')s reported recycling rates that did not meet minimum state standards:5

materials recycled in 2008 in Virginia, in tons

Source: statistics from Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), The Virginia Annual Recycling Rate Report: Calendar Year 2008 Summary

Special programs facilitate recycling of computers, electronics, and household hazardous waste (paints, pesticides, batteries, etc.). Urban areas offer more opportunities for recycling such materials, while rural areas may offer just an annual or quarterly opportunity to recycle items that require special handling.

Since each jurisdiction must spend additional funds to process computers, electronics, and household hazardous waste, typically only residents or property owners in that jurisdiction may take advantage of the recycling opportunities - waste management is a function primarily of local government. Some companies, such as BestBuy and Verizon, offer to recycle electronics at their stores independent of a customer's residence.

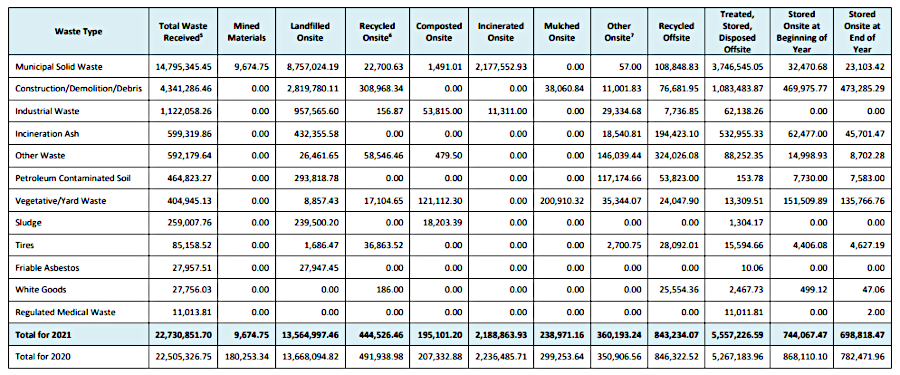

Solid Waste Managed in Virginia for All Reporting Facilities in Tons – 2021

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2022 Annual Solid Waste Report for CY2021 (Table 1)

By 2022, there were 204 solid waste facilities with permits from the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. About 25% of the waste processed was imported from other states, primarily Maryland, New York, and New Jersey plus the District of Columbia.

There were 50 solid waste landfills in Virginia. Of that total, six had no remaining capacity to accept more waste, and five more expected to be full within 10 years. Of the 14 permitted Construction and Demolition Debris landfills, one had reached capacity and five others had less than 10 years remaining.

Of the six incinerators, one was at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and one was at the Pentagon. The others were located in Alexandria, Fairfax County, Hampton and Portsmouth. The incinerators processed roughly 10% of the tonnage brought to municipal solid waste landfills.6

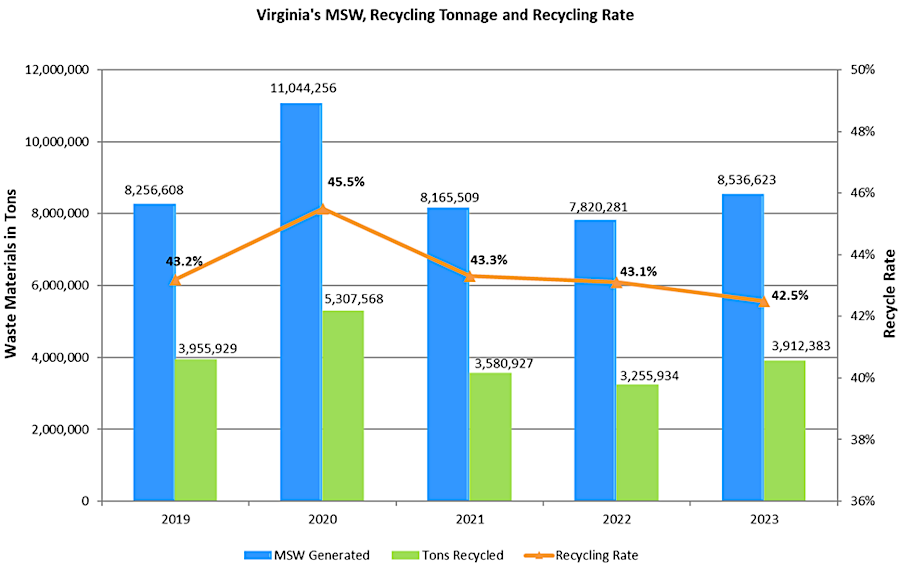

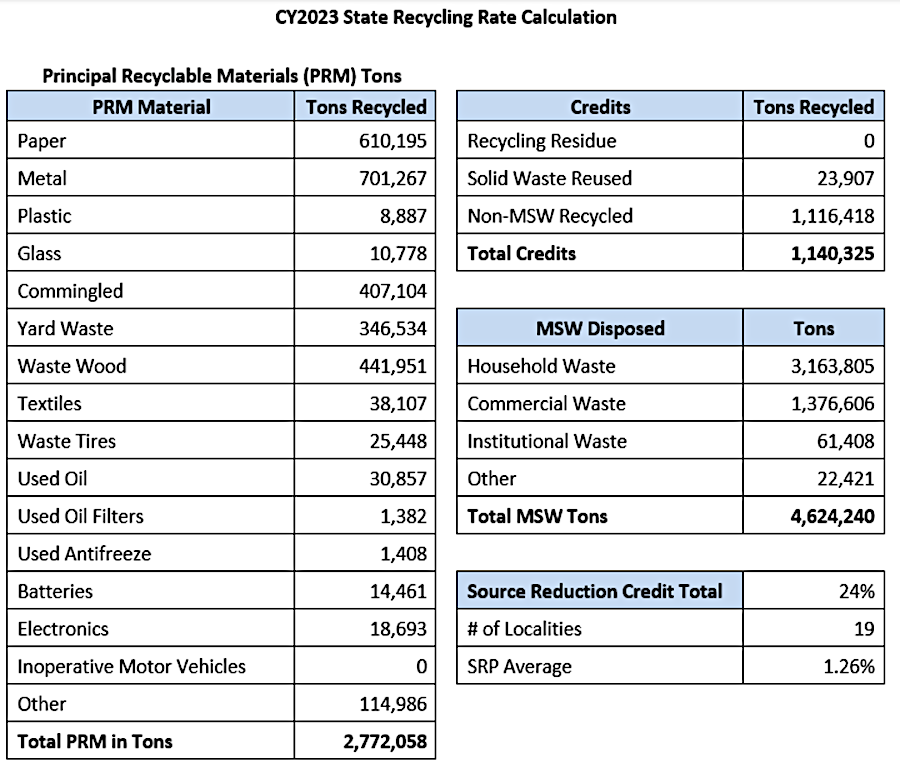

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) reported a 42.5% recycling rate in 2023. That percentage reflected reports from 126 Virginia cities, counties, and towns; 29 Solid Waste Planning Units (SWPUs) with populations of 100,000 or less were not included.

In addition, 425 tons of electronics were recycled in 2023. State law requires companies that manufacture 500 or more computer units for sale in Virginia to offer consumers free recycling.

Virginia does not require a deposit on each bottle or can when purchased. Only 10 states have such a "bottle bill," with the deposit refunded whenan empty bottle is recycled. In 2023, just 8% percent of plastic bottles were recycled in Virginia. That contrasted with 75% in Maine and 71% in Oregon, which have bottle bills.7

over 40% of municipal solid waste was recycled in 2023

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), CY2023 Virginia Recycling Rate Report