a modern reconstruction of the earliest house known in Virginia started with building a framework from small saplings cut with stone axes

Source: Center for the Study of Early Man, The Flint Run Paleohouse Reconstruction (1986)

a modern reconstruction of the earliest house known in Virginia started with building a framework from small saplings cut with stone axes

Source: Center for the Study of Early Man, The Flint Run Paleohouse Reconstruction (1986)

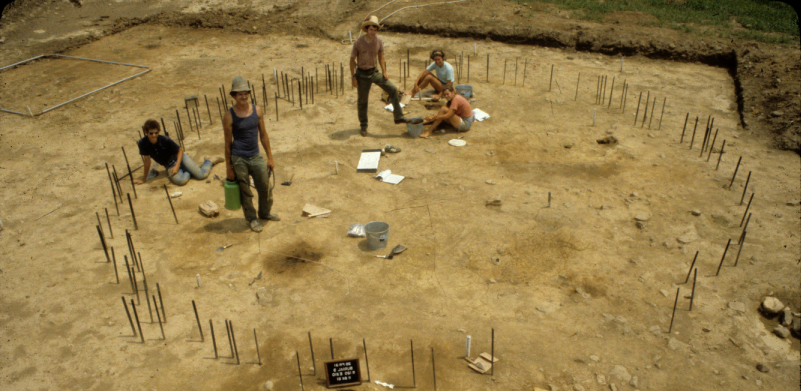

During the Paleo-Indian Period, hunting and gathering bands were constantly on the move. One of the oldest structures in North America has been identified at the Flint Run Archaeological District along the Shenandoah River in Warren County. Based on evidence in post molds, archeologists reconstructed an oval house built about 10,000 years ago.

The unique value of the high-quality jasper at the Thunderbird quarry near Flint Run made it worthwhile to build perhaps the first house in what is now Virginia. People could stay for a longer period in one location, carve out jasper from the ground, make a few tools immediately, then carry chunks of jasper away for creation of future tools. When the supply of jasper was used up, a return visit to the quarry may have included re-occupying the house there. It is even possible that different bands of Paleo-Indians may have shared the space, rather than fought over the right to use it during a visit. In that case, the structure was Virginia's first hotel.

Reconstructing the house started by cutting down saplings up to four inches thick with axes made from jasper. That rock was quarried at the Thunderbird site, and was the reason for Paleo-Indians to construct a house there originally. Using a mallet, stakes were pounded 18" into the ground and then removed, creating holes for placing the sapling poles. The archeologists tied the tops of the poles together to create arches before installing in the holes, avoiding the need for ladders.

Because the site was cold at the end of the Ice Age, the arches were bent as much as possible to create a low roof so the compact interior required less effort to keep warm. The structure had the equivalent of a hallway near the door. That created a space to remove heavy robes and shake off snow before entering the living space.

Grass may have been used for insulation, since there were few large trees at the time from which slabs of bark could be removed. The waterproof roof may have been made from caribou hides or up to 200 deer skins, since mastodon hides would have been hard to obtain. The house would have been occupied during the coldest months. The people quarrying jasper at Thunderbird slept in less-crowded settings when weather was warmer.

The structure took substantial effort to build, and probably required replacing the skins on the roof each winter as they began to leak. The first geologists in Virginia who recognized the distinct value of cryptocrystalline jasper for making sharp tools were also savvy enough to be architects. As described by archeologists:1

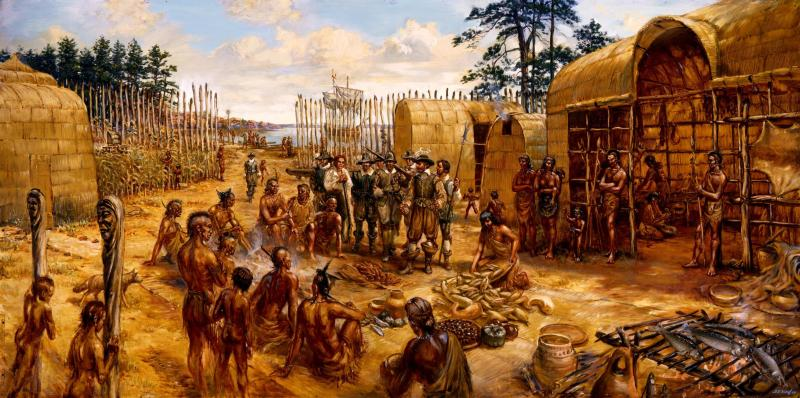

the English who reached Virginia in 1607 discovered that Native Americans built yi-hakans (houses) from saplings and reeds, and towns were often surrounded with wooden palisades

Source: National Park Service, Jamestown - Sidney King Paintings, Trading With the Indians

Permanent houses and towns became common as agriculture was adopted, a time identified by archeologists as the Woodland Period starting 3,000 years ago. Groups of people settled down in one place to nurture crops through the growing season, particularly after corn became a common crop about 1,000 years ago.

Farming was a seasonal occupation. People staying in one place for several months at a time invested more heavily in creating comfortable shelters before resuming travels for hunting and gathering during the winter. The architecture and construction techniques for food storage units, sweat lodges, and other buildings were similar to houses. Saplings/branches, bark, and reeds were readily available.

The model for early Woodland Period housing was likely a simple expansion of the temporary structures built during the seasonal rounds of the Archaic Period. During the Archaic Period (8,000 BCE-1,000 BCE), bands of Native Americans would hunt in a stream valley for perhaps a week. The family group would then move to another location nearby, one where game, berries, fruits, and other plant material had not been harvested recently.

Shelters built for just several days of occupation during a hunting and gathering expedition would have been watertight, but shelters built for a stay of several months would have been larger and more comfortable. A family living inside a structure all summer would build platforms for raised beds and nooks for storage, including pits in the ground. To increase air circulation on hot days, parts of the exterior wall coverings would have been easy to remove and then replace at night.

Assuming human nature has not changed, the design of the early houses reflected both the needs of the residents and their social status. Interior layout would have accommodated the size of a family or group living together. Exterior decoration would have reflected their relative significance within the traveling band.2

To the frustration of both Native American residents (and later archeologists), the organic materials using in Native American structures decayed after a few years. Repairing a home was a constant process, though the materials in houses was kept dry in the summer due to constant small fires kept burning in the earth floor.

At the start of the Woodland Period, houses in "permanent" settlements were not occupied for 12 months at a time. Food harvested in the fall was not sufficient to feed everyone until the next crop was ready a year later. The animals and plants nearby had been exhausted by people who had settled in one place for three or more months during the summer to protect their crops - so the people left their houses and engaged in hunting and gathering again during the winter.

The materials in the structure would get moist and decay once the constant fires were no longer kept burning. People returning to the farming site at the start of spring always faced the need to reconstruct their houses. The framework of wooden saplings left behind for each house may have been standing in the spring, but the fibers binding the wood pieces together had to be rewound and the bark/reeds covering the house had to be replaced.

residents at Werowocomoco made frameworks from local branches and covered then with reeds from the Purtan Bay swamps

Source: National Park Service, Werowocomoco Planning

During the Mississippian Period, Native Americans built mounds, plazas, platforms, and earthworks in their towns. Mounds which included burials were built in southwestern Virginia and north into the Shenandoah Valley, with some in the headwaters of the Rivanna River on the eastern side of the Blue Ridge.

The mounds and platforms offer evidence of social stratification within communities at that time, with elites having access to specialized structures. Most of those non-domestic structures for gatherings and ceremonies were plowed flat starting in the 1720's, when colonists crossed the Blue Ridge and planted their crops.

Stone structures, including cains and walls, still remain from the Mississippian Period.3

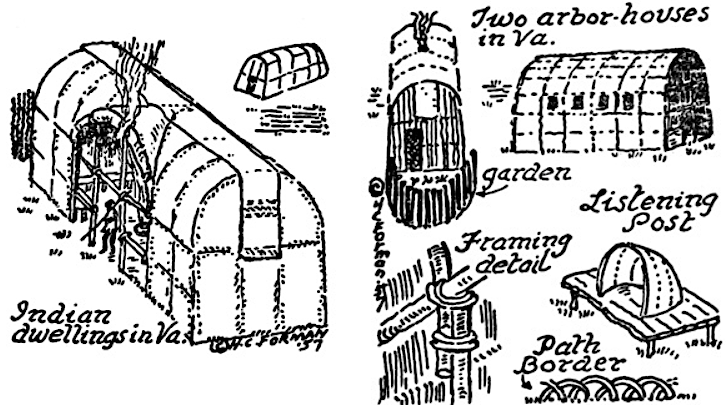

When Spanish colonists in 1570 and English colonists in 1607 first arrived on the Atlantic Ocean coastline, they encountered Algonquian-speaking Native Americans that used local saplings to form the frame of their houses called "yi-hakans." The exterior roofs and walls were made from mats of cattails collected when dry from swampy areas or from bark peeled from nearby trees. They did not use clay like the English to make wattle-and-daub structures, or to seal gaps in the bark or reed mats.

Wood used for Native American houses were branches and saplings, perhaps no more that four-five inches in diameter and often smaller. Before Europeans brought sharp metal tools, it was not feasible for the Native Americans to harvest large trees and make lumber for houses. There were no log cabins even after the English arrived. The Swedes who came to Delaware Bay introduced that style of housing in the mid-1600's.

English colonists at Jamestown were already aware of Native American housing patterns, which Roanoke Island colonists had seen two decades earlier

Source: US Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library, The Village of Pomeiooc (by John White, 1593)

this yi-hakin at Henricus Historical Park, made from reeds and bark, had lasted four years by 2017

The Native Americans in Virginia weaved their houses together. Vines and plant fibers, woven into twine, were used to bind together the mats of reeds. The sapling poles were also tied together, so the structures withstood the winds of summer thunderstorms and the snow loads in the winter. The lower ring of mats or bark could be lifted up or removed in the summer to cool the interior.

Reeds were plentiful on the Coastal Plan near swamps, and trees were everywhere. Making the reed mats and attaching them to the house required manufacturing up to a mile of twine, per house, from local plant fibers.

organic stains in the soil ("postmolds") allow archeologists to identify where small poles formed the framework for Native American houses

Source: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Late Woodland

In Powhatan's territory, English colonists recorded that the women gathered materials and constructed the houses. The labor involved in house construction was substantial. When the women could not find saplings of the desired length and width, they could get stronger men to use stone axes to cut wood. Most of the labor involved making the twine and mats or stripping the bark. Actually assembling the house required less time than making the components.

On the Coastal Plain, houses were oval or circular. The longest dimension was about forty feet, except for the homes of weroances (chiefs) and the special temples ("quiocosins") built for kwiocosuk (shamans). Everyone entered and left through a single door. Modern interpretive structures, built at places such as Jamestown Settlement, have more than one door to facilitate the movement of visitors.4

Henry Spellman lived with Chief Powhatan and then the Patawomekes between 1609-1611. He wrote in 1613 "Of ther Tounes & buildinges." Spellman reported that the houses of Powhatan and weroances were designed to provide security against an attack, while the women could build houses for others men quickly so they had a place to sleep during a hunting expedition:5

Native Americans used stone axes to cut trees and make palisades, until getting access to metal axes made by Europeans

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Axe head

Men may also have been recruited to cut the bark from trees such as tulip poplar, then haul the heavy slabs back to town. Bark was easiest to cut and peel from trees in the springtime as sap was rising. House repairs and construction were easier when bark was flexible; in the winter, bark was too brittle.

After soils were exhausted by farming, it made sense to move the house several hundred yards away. Disassembly and reconstruction would have recycled many of the house components. The organic building materials used for roofing and siding would have lasted only a few years before rotting, but smoke from the constant fires may have preserved the reeds and bark:6

the interior framework was exposed in yi-hakins during the summer, but covered by mats, skins, and furs during the winter for extra warmth

Reconstructions of such housing for exhibits for interpretive exhibits at such places as Jamestown may require new thatching of the roofs and walls after several years. The material rots quicker than in original yi-hakins, in part because the structures are unoccupied at night and in winter when exhibits are not staffed.

The branches and saplings used for framing can survive many years, but fungi and bacteria grow quickly in moist reeds. The fibers holding the mats of reeds together need to be maintained regularly.

Henricus Historical Park constructed four yi-hakins, and three were covered with store-bought mats in 2017

Native Americans in Virginia kept a small fire burning every day in their houses. The heat and smoke deterred decay of the building materials, and the need to replace reeds was lower. A structure might last with minimal repair until the nearby soil was exhausted after 3-7 years, and it was time to move and plant new fields. The framing and mats of reeds would be moved, but new reeds also would be installed as needed at the new location.

Native American houses in Virginia had a hole in the roof for smoke to escape, with a sheet of bark to keep out rain

Thatch is still a common building material in some areas. In Guatemala's Peten region, local residents build two structures. The metal-roofed house is used at night, but a thatched roof structure is used for cooking and activities during the day. Residents prefer to sleep in the metal-roofed structure that does not smell of smoke from cooking fires, while that smoke helps to extend the life of the thatch roof in the separate structure.

home of a farmer neat Topoxte in Guatamala, showing thatched-roof structure used for cooking next to metal-roofed house

If a strong storm blew down a structure, the material needed to rebuild it quickly was readily available in the local area. Native Americans could rebuild their houses easily. When soil fertility declined after years of growing corn, whole towns could be moved a short distance to be closer to new fields.

Mats of reeds and bark coverings could be taken off the sapling framework of a house, the saplings could be take apart, and the structure moved in pieces to the new location. Vines twisted around the pieces as they were reassembled provided greater stability, allowing houses to withstand the wind and rain of summer thunderstorms.

Palisades around towns could be rebuilt, providing some security from surprise attack by enemies and excluding wild animals attracted by the food within the town. Like houses, palisades were made of locally-available materials. Small trees and branches were cut to create a frame for a palisade wall. Vines and more branches were woven into the wooden framework, creating a barrier that would deter animals and delay an enemy. To strengthen the wall and prevent an enemy from setting it on fire, mud could be smeared between the branches.

Colonists used a similar process to create "wattle and daub" structures at Jamestown. Starting in 1607, the first English colonists built their structures inside the fort at Jamestown with wooden frames, then applied local clay to the exterior to create "mud and stud" structures. Where the English bult roofs with an overhang to block rain, the walls could survive for years.

Without a stone or brick foundation, however, the wooden frames in Jamestown rotted soon in the moist soil. Iron axes and other carpentry tools allowed the English to cut trees and saw large timbers for the framework and for a palisade, and to use iron nails rather than vibes to attach pieces.

the wooden frame of a palisade could be covered with mud to create a more-effective and fireproof wall

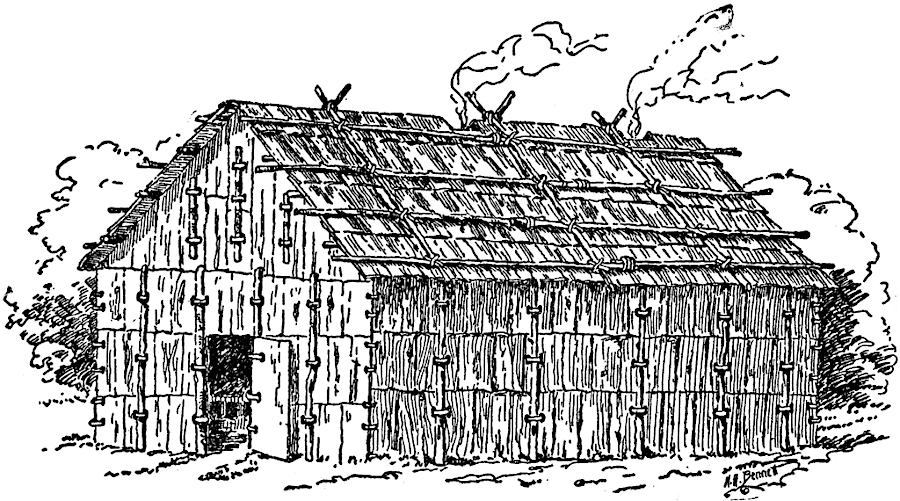

West of the Fall Line, the Siouan-speaking Native Americans built houses similar to those of the Algonquian-speaking nations. South of the James River, however, the Iroquoian-speaking groups in the watersheds of the Blackwater, Nottoway, and Meherrin rivers had a different approach. They built rectangular "long houses" with bark coverings, similar to those constructed by Iroquoian-speaking members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in New York.

Iroquoian-speaking groups in the watersheds of the Blackwater, Nottoway, and Meherrin rivers build longhouses rather than yi-hakins

Source: Florida Center for Instructional Technology, Bark house of Iroquois

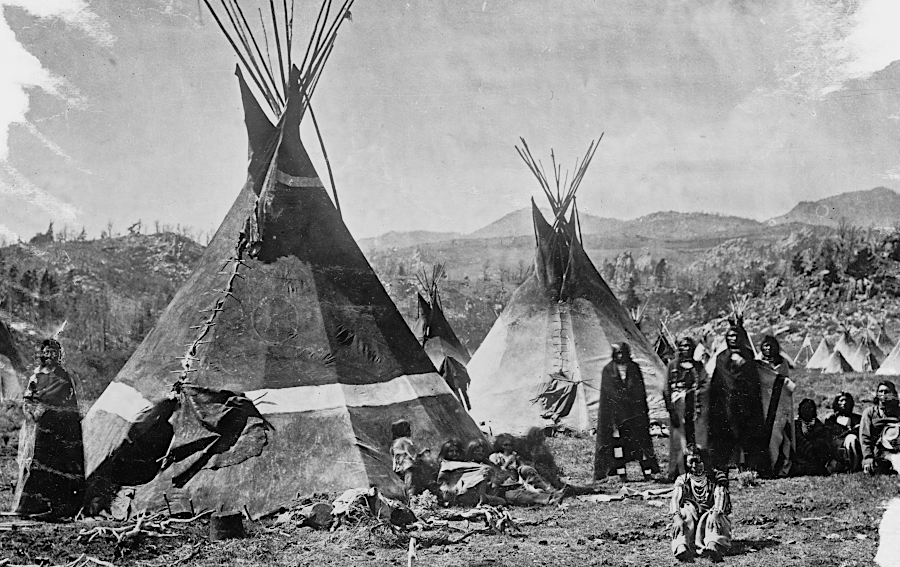

There were no teepees in Virginia made from animal skins, in contrast to the housing constructed by Native Americans on the Great Plains where trees were scarce. In Virginia, with 40-50 inches of rainfall each year, bark and reeds were readily available when settlements became common during the Archaic Period starting 8,000 years ago (6,000 BCE). By then the climate had warmed and trees grew large enough to provide large pieces of bark, so animal skins were used for clothing and bedding rather than as a building material.

teepees with buffalo hides (later canvas) were used on the Great Plains west of the Mississippi River - no Native Americans in Virginia built teepees

Source: Library of Congress, Skin tepees, Shoshone Indians

Native Americans used branches, bark, and reeds to create yi-hakins, longhouses, and other structures

Source: Henry Chandlee Forman, Virginia Architecture in he Seventeenth Century