the initial boundaries for Lord Calvert's colony gave all of the Delmarva Peninsula to Maryland

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia, Marylandia et Carolina in America septentrionali Britannorum (by Johann Baptist Homann, published c.1759)

the initial boundaries for Lord Calvert's colony gave all of the Delmarva Peninsula to Maryland

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia, Marylandia et Carolina in America septentrionali Britannorum (by Johann Baptist Homann, published c.1759)

The initial boundaries for Lord Calvert's colony gave all of the Delmarva Peninsula to Maryland. Virginians objected, because there were already colonists established on the southern part of the peninsula. The final charter was modified, defining an east-west line that today separates Accomack County in Virginia from Worcester and Somerset counties in Maryland.1

While all of Maryland was once part of Virginia, the Virginians fought physically (with guns, resulting in deaths) to assert control over only two parts: Kent Island and the Chesapeake Bay.

William Claiborne was the Secretary of State in the Virginia colony after 1626, and used his influence to partner with London-based capitalists to build a fur trading post in the upper Chesapeake Bay on Kent Island. He named the island after his home county in England, after exploring the upper Chesapeake Bay in 1627. The plan was to trade with the Susquehannock and other tribes, competing with the Dutch and Swedes in New Amsterdam (New York) and Delaware. In addition, a plantation on the island was expected to provide food and other resources for trade with New England.2

Claiborne knew, from George Calvert's visit to Jamestown in 1629, that a rival (and Catholic) colony could be created north of the Potomac River. Claiborne sailed from Jamestown back to London to lobby against the grant to the Calvert family. To bolster the claim that Kent Island was already settled, he sailed back across the Atlantic Ocean to Kent Island. He built a plantation, and stocked it with indentured servants and a herd of cattle.3

Charles I issued Claiborne and his partners a license for trading in "corne, furs and any other commodities whatsoever." Claiborne never had a land grant for private ownership of Kent Island, but he did claim to have purchased the property from the Native Americans in 1631. The settlement sent a representative to the General Assembly that met in Jamestown in 1632.4

After Charles I signed the 1632 charter granting Maryland to the Calverts, the Virginia colonists maneuvered so the new colony would fail. Charles I's colonial governor in Virginia, John Harvey, wrote back to London that the Virginians "would rather knock their cattell on the heads then sell them to Maryland."5

The 1632 grant to Lord Baltimore abolished Claiborne's claim to Kent Island, but he fought to retain control. Claiborne appealed to English officials in London, citing his occupation of the island prior to the grant. Claiborne also supported a political reaction in Virginia that "thrust out" colonial Governor William Harvey, forcing him to return to England in part because he would not oppose Charles I's grant to the Calverts.

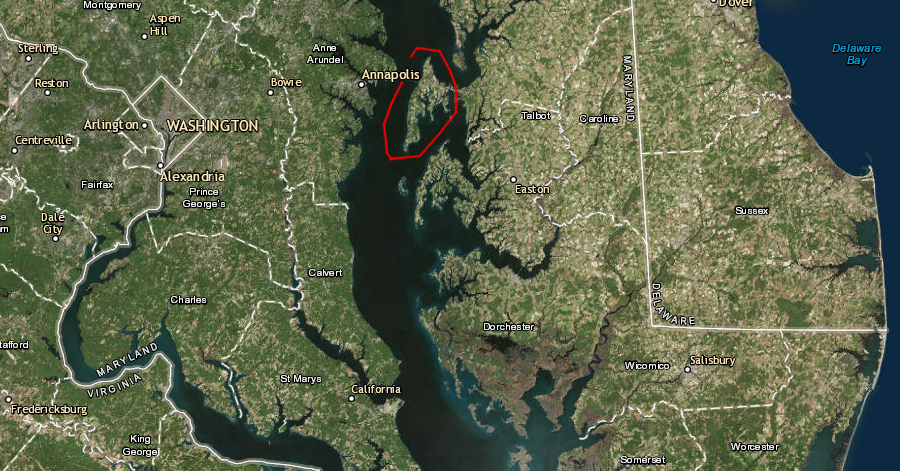

Kent Island is clearly within the territory granted to Lord Baltimore in the 1632 charter

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

The first Maryland colonists arrived on the Ark and Dove in 1634. The next year, supporters of Claiborne and Calvert fought a minor civil war in the Chesapeake Bay. The fighting began when a ship owned by Claiborne seized a ship owned by the Maryland colonial government, in the first documented act of piracy in the Chesapeake Bay. Marylanders spotted Claiborne's ship, on a later trading mission, and captured it in return.

Both Claiborne and the colony then outfitted new ships for battle, and Claiborne essentially declared war against Maryland. After armed clashes at sea, Gov. Calvert sent a small army that captured Kent Island. Three Virginians died in the fighting.6

Maryland established complete control over Kent Island in 1637, after Claiborne's creditors in England realized the fur trading had not been profitable. They sent a replacement for Claiborne and decided to accept Maryland's authority. In 1638, Claiborne's appeal to the Commissioners for the Plantations in London was rejected. In 1644, however, Claiborne seized his old fur trading post again during an anti-Catholic uprising that was triggered by Virginians.

location of Kent Island

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas

The Calverts regained control in 1646, but the relationship remained strained between the Catholic owners of the proprietary colony and the Protestant settlers in Maryland. Colonial officials in Virginia were sympathetic to the Maryland Protestants. Their religious differences between the rulers in the St. Mary's and Jamestown were more important than the shared characteristics of class and wealth.

William Claiborne once again stimulated another brief revolt in 1654 during the English Civil War. In the end, the Calvert's were reinstated as the leaders of the Maryland colony and Kent Island restored to Maryland control.

Claiborne made a last attempt in 1677. After Bacon's Rebellion, royal officials reviewed the conditions and role of colonial officials in Virginia. Claiborne was almost 90 years old, but still ambitious enough to lobby to have Kent Island restored to his control.

Though he never regained the island, his name lives on in horseracing circles. Claiborne Farm in Kentucky, breeder of numerous winners of the Kentucky Derby and other top stakes races, was established by descendants of Claiborne who named the farm after him.7

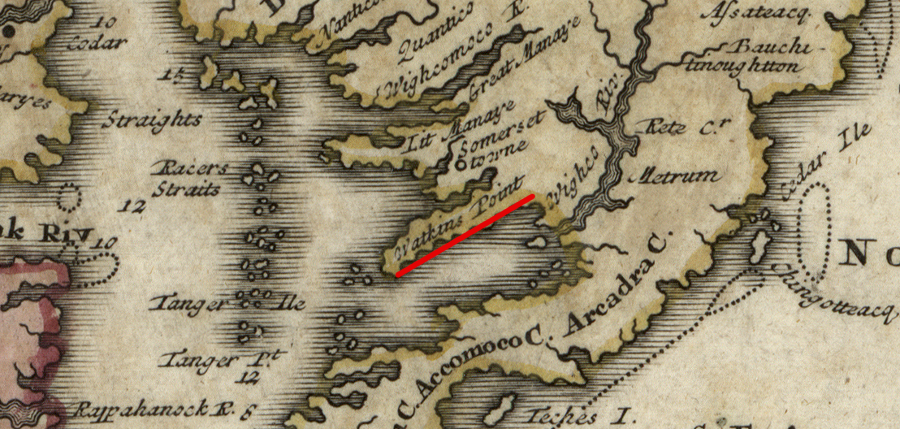

According to the 1632 charter for Maryland, the Delmarva peninsula was divided between Virginia and Maryland. Starting at Watkins Point on the western side of the peninsula "near the river Wigloo," a line drawn due east to the Atlantic Ocean separated the Virginia part of the peninsula from the Maryland part on the north. (Delaware, the "del" part of Delmarva, was created later.)

John Smith's map of Watkins Point, Cinquack, and the river Wighco (note map orientation, with west at the top)

Source: Library of Congress - Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606

Augustine Herrman's map, prepared for Lord Calvert in the 1660's, placed Chincoteague north of the double line of trees and thus within Maryland

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman)

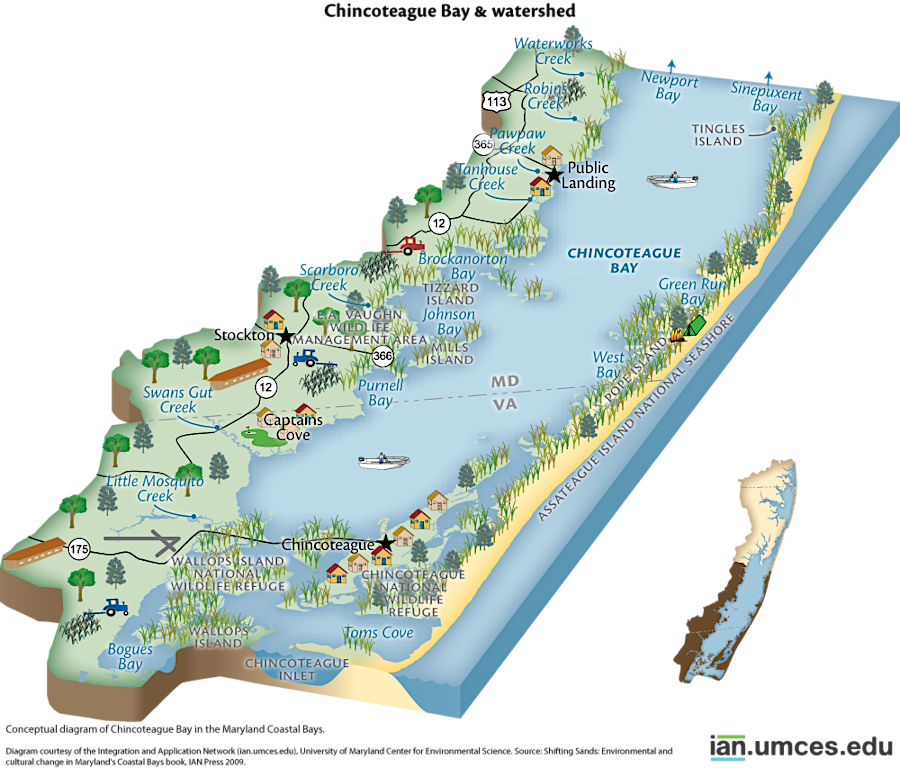

the modern Maryland-Virginia border splits Chincoteague Bay and Assateague Island, but Chincoteague Island is within Virginia

Source: Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Shifting Sands: Environmental and cultural change in Maryland's Coastal Bays (by Jane Thomas)

The Chesapeake Bay was divided between Virginia and Maryland by another line, from "Cinquack" near the mouth of the Potomac eastward across the bay to Watkins Point. Cinquack was an Algonquian town marked by John Smith on his map of Virginia. The town was located six miles south of the mouth of the Potomac River, but Maryland accepted that the colony's southern boundary on the west side of the Chesapeake Bay started at Smith Point rather than Cinquack.

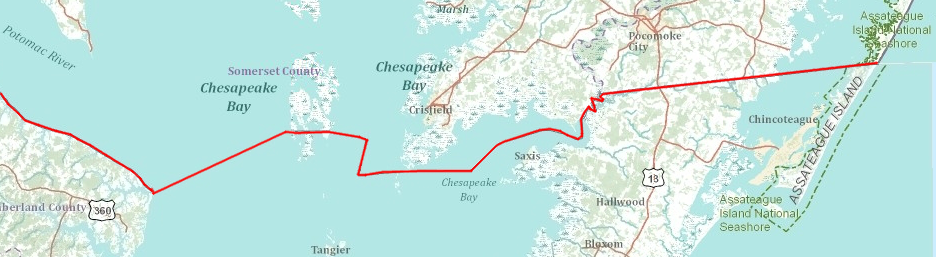

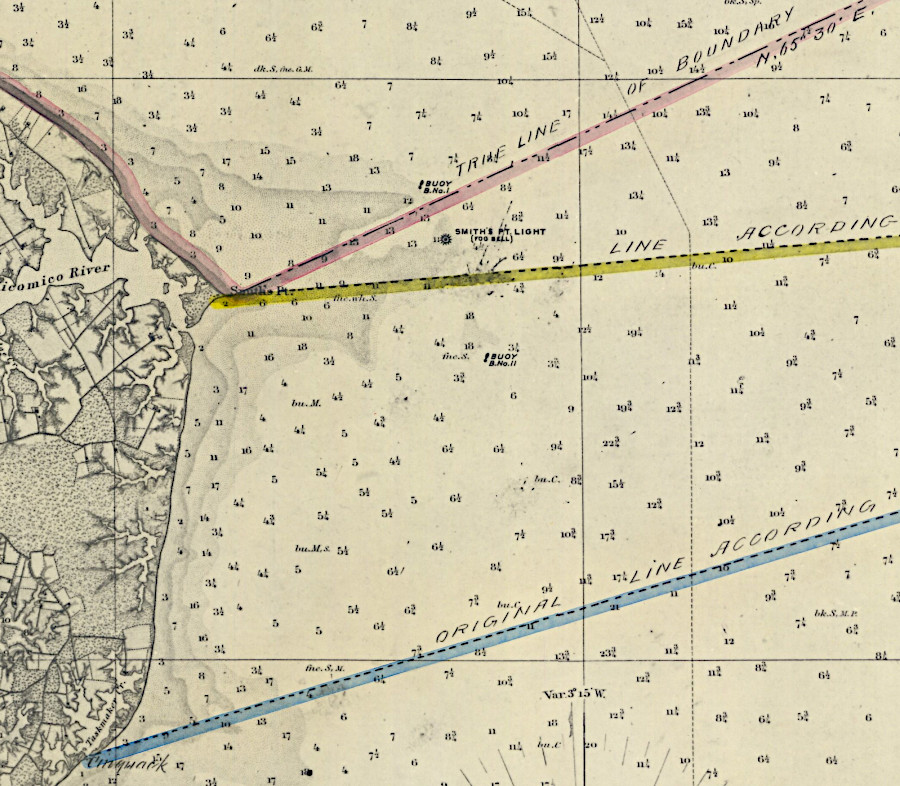

line from Smith Point across Chesapeake Bay to Watkins Point, as defined in the 1632 charter

Source: Southern Boundary of Maryland, (by Thomas J. Lee, 1860)

Maryland did not claim an extra portion of the Chesapeake Bay by trying to draw the line from the old location of Cinquack, across the Chesapeake Bay to Watkins Point. However, the theoretical straight line defined in the charter has been modified over time. It now zig-zags north to give Virginia some of the oyster-rich areas of Smith's Island, and bends south to give Maryland more control over oyster beds near Pocomoke Sound.

in the 1632 charter for Maryland, the original boundary included a straight line across the Chesapeake Bay to Watkins' Point on the Eastern Shore, and then another straight line from Watkins Point due east to the ocean - but the border was altered in the 1877 Black-Jenkins award

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

The boundary on the Eastern Shore between Watkins Point and the Atlantic Ocean was not surveyed or marked when the area was settled by religious dissidents, primarily Quakers and Puritans who had been expelled from Virginia in 1660.

After the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 made clear that the Puritans had lost political control in England, Governor Berkeley and Virginia officials imposed restrictions on rebels of various sorts. The religious dissenters from Virginia who had settled on the Eastern Shore could move to Maryland, which offered greater toleration for non-Anglican settlers. In addition, if the boundary was not defined, some settlers could choose to avoid paying taxes to either colonial government by rejecting the authority of any court system to enforce colonial laws.

The Surveyor General of Virginia, Edmund Scarborough, aggressively asserted Virginia's claims to land on the Eastern Shore. Scarborough had few qualms about encroaching upon territory that theoretically was controlled by a Catholic-dominated colony. Several times he led armed parties north of the presumed boundary, claiming properties were in Virginia.

Cinquack and Watkins Point at the mouth of the Pocomoke river (originally called the Wighco) defined the Virginia-Maryland border

Source: Maryland State Archives, Nova Terrae-Mariae tabula (by John Ogilby, 1671)

To clarify which colony controlled the Eastern Shore territory, Philip Calvert of Maryland (uncle of the governor at the time, Charles Calvert) and Edmund Scarborough agreed in 1668 to set the boundary along the 38th parallel, the latitude at which they estimated the Potomac River emptied into the Chesapeake Bay.

They had the Calvert-Scarborough line surveyed. It started where the 38th parallel crossed the Pocomoke River, rather than on the edge of the Chesapeake Bay, perhaps to avoid difficult-to-traverse marshland seen as having minimal value. Between the edge of the Chesapeake Bay and the Calvert-Scarborough survey starting point in 1688, the colonial officials used the winding main channel of the Pocomoke River to mark the colonial boundary. That decision altered the straight-line 1632 charter boundary on the Eastern Shore, and gave Maryland some extra marshland on the peninsula north and west of the Pocomoke River.

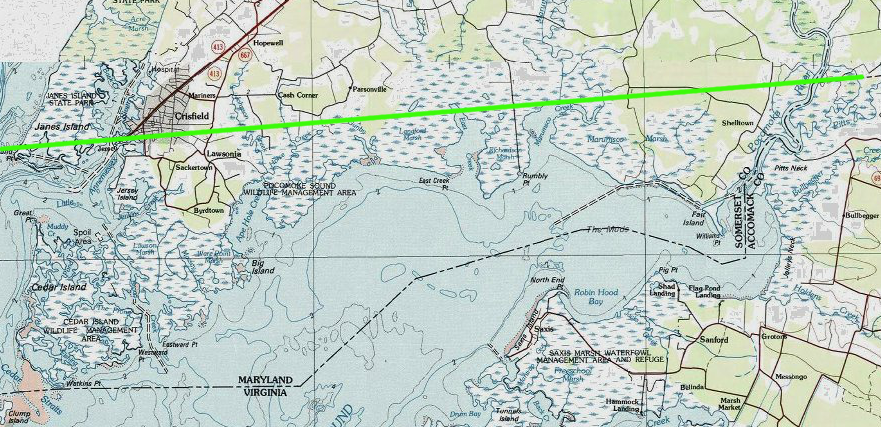

1632 charter defined the area below the green line as part of Virginia, but the Calvert-Scarborough line established new boundaries in 1668 before the 1877 Black-Jenkins award

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

From the Pocomoke River eastward to Chincoteague Bay, the 1668 Calvert-Scarborough line was surveyed with magnetic compasses without correcting for the deviation from true north. A compass does not point to the geographic North Pole; it points to magnetic north - a location near, but not at, the geographic pole. The 1688 boundary line is about 5 degrees off from a true east-west direction. The line "tilts" to the northeast on the map, rather than runs due east. As a result, about 15,000 extra acres east of the Pocomoke River ended up in Virginia.8

a boundary than ran east-west from Watkins Point would have put the northern edge of Accomack County into Maryland

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

That 1688 survey did not resolve where the state line crossed the Chesapeake Bay and its various islands, between Cinquack and Watkins Point. Virginia claimed that the exact location of Watkins Point was unclear by the 1850's. As described in a later arbitration document that helped resolve the dispute:9

at the time of the Civil War, Virginia and Maryland disputed where the state boundaries would start on the western edge of the Chesapeake Bay

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Historical Map and Chart Collection, Chesapeake Bay Sheet #3 Potomac Entrance Tangier and Pocomoke Sounds (1863)

Watkins Point and MD-VA boundary, as drawn by Augustine Hermannn in 1670

Source: Library of Congress - Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670

Watkins Point in 1714

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia, Marylandia et Carolina: in America septentrionali Brittannorum industria excultae (by Johann Baptist Homann, 1714)

Watkins Point and MD-VA boundary, as drawn by John Senex in 1719

Source: Library of Congress - A new map of Virginia, Mary-Land, and the improved parts of Pennsylvania & New Jersey

Watkins Point and MD-VA boundary, as drawn by John Fry/Peter Jefferson in 1755

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (by Joshua Fry, Peter Jefferson, 1755)

Watkins Point and MD-VA boundary, as drawn by John Fry/Peter Jefferson (left) and John Mitchell (right) in 1755

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the British and French dominions in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements (by John Mitchell, 1755)

Watkins Point and MD-VA boundary, as drawn by Thomas Jefferson in 1787

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the country between Albemarle Sound, and Lake Erie, comprehending

the whole of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware and Pensylvania, with parts of several other of the United States of America

In the 1850's, after many initiatives from the Maryland side, Virginia agreed to resolve the boundary along the entire Potomac River, from the Fairfax Stone at the headwaters to the mouth of the Potomac River at Smith Point. At the request of both states in 1858, Lieutenant Michler of the United States Topographical Engineers surveyed the shorelines of the Eastern Shore and Chesapeake Bay islands. Michler documented the shoreline of the Potomac River, but then the Civil War interrupted efforts to negotiate between the states.

After the Civil War, Maryland and Virginia disagreed on how to manage the oysters in the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland did not allow dredging, but Virginia permitted boats to scrape the bottom of the bay and disrupt the natural habitat. "Oyster pirates" were accused of harvesting illegally on either side of the border.

a 1752 map, drawn before the value of Chesapeake Bay oyster beds was recognized, placed Tangier and Smith islands in Maryland

Source: Library of Congress, A new and accurate map of Virginia & Maryland: laid down from surveys and regulated astronl. observatns. (by Emanuel Bowen, 1752)

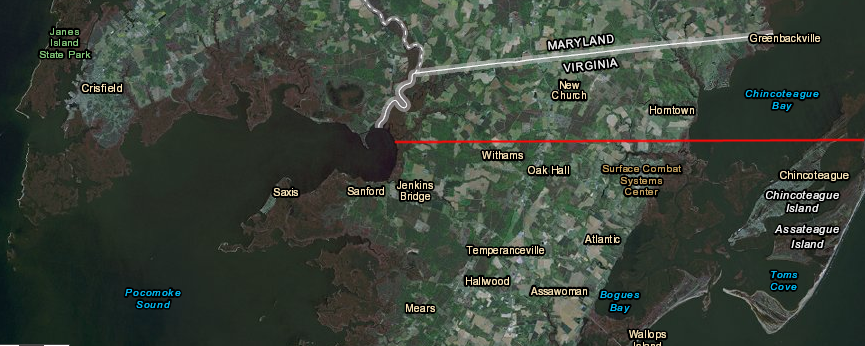

The Wigloo (or Wighco) mentioned in the 1632 Maryland charter was recognized as the Pocomoke River, but Virginians wanted to harvest oysters in all of Pocomoke Bay. In the debate, Virginia even attempted argued that "Watkins Point" was the mouth of the Annamessex River north of Crisfield.

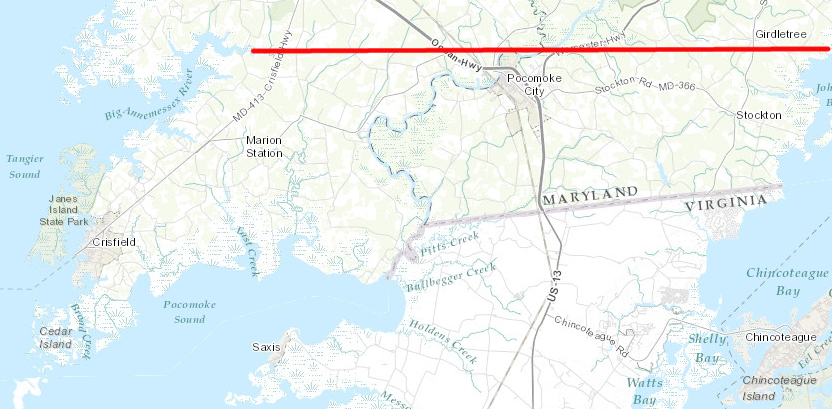

if the mouth of the Big Annamessex River had been defined as Watkins Point, Virginia would have owned all of Pocomoke Sound

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

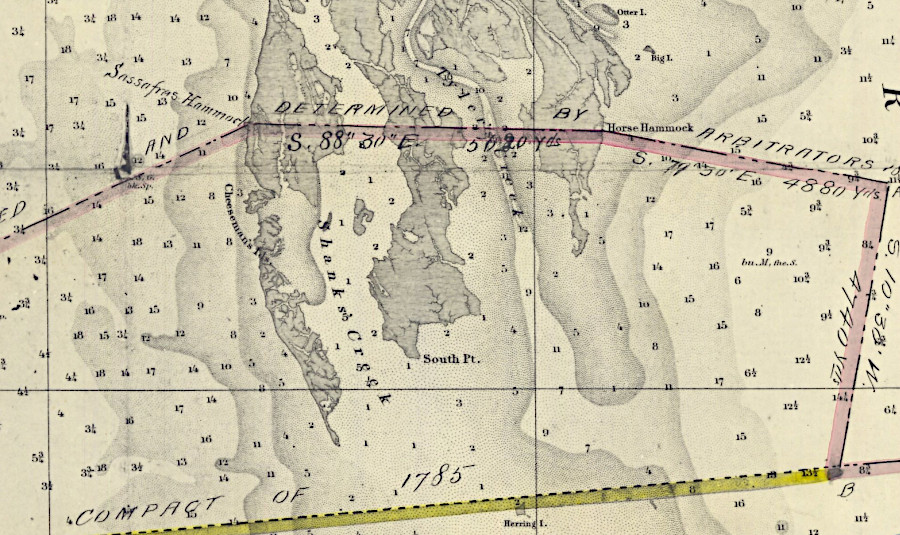

In 1877, the Black-Jenkins arbitration decision determined that the extreme southwestern point of Somerset county in Maryland at Cedar Straits was the location of "Watkins Point" referenced in the 1632 charter. That decision also affirmed the locally-accepted boundaries between Horse Hammock-Sassafrass Hammock, on Smith's Island.

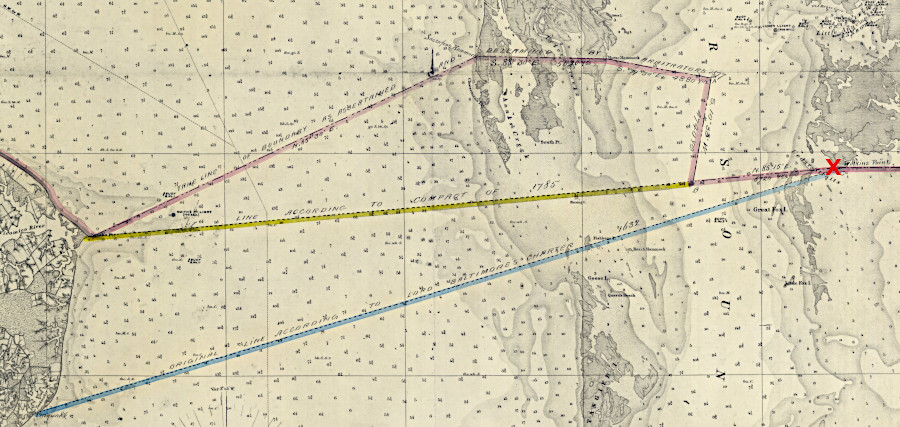

the 1877 line drawn by Black-Jenkins arbitrators (pink) divided Smith Island, whereas a straight across the Chesapeake Bay (yellow) would have placed the entire island in Maryland

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Historical Map and Chart Collection, Chesapeake Bay Sheet #3 Potomac Entrance Tangier and Pocomoke Sounds (1863)

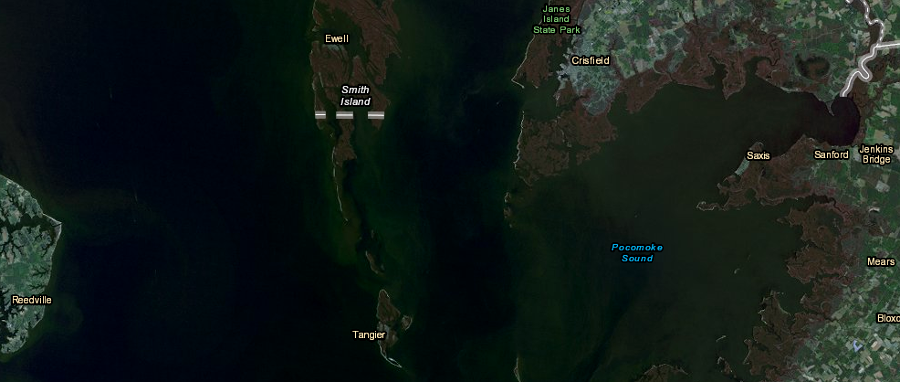

Through that 1877 arbitration, the two states agreed that the low-water line would mark the boundary on the Potomac River, but on the Eastern Shore the "middle thread of the Pocomoke River" would be used. The adoption of twists and turns in the Maryland-Virginia boundary throughout the Chesapeake Bay, rather than a straight line across the water, granted rights for Virginians to harvest the valuable fish and oyster resources of:10

oysters, not land, was the primary resource that both Virginia and Maryland sought to control in the Chesapeake Bay

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

arbitrators defined a spot to be called Watkins Point (red X), and drew a zig-zag boundary (pink) rather than a straight line (yellow)

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Historical Map and Chart Collection, Chesapeake Bay Sheet #3 Potomac Entrance Tangier and Pocomoke Sounds (1863)

Resolving the boundary did not resolve the conflicts between Virginia and Maryland. Dredgers based at Colonial Beach would sneak across the boundary and scrape oysters from submerged lands owned by Maryland, while Marylanders on the Eastern Shore would remove oysters from Virginia waters.

In the 1860's, both Virginia and Maryland had sought to enforce their authority over oysters within state waters by establishing "Oyster Police Navies" on the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. The Virginia Board of the Chesapeake maintained armed steamers on the bay, theoretically to protect Virginia watermen from shoot-outs between Maryland and Virginia fishermen. The Virginia governor personally led two Oyster Navy expeditions in 1882-83 to capture oyster pirates at the mouth of the Rappahannock River. Virginia's Fisheries Commission inherited the Oyster Navy in 1897, and added two other steamers.11

After World War I:12

Disputes about which state could enforce varying rules about dredging oysters, etc., continued, leading to adoption of another Maryland-Virginia Compact in 1958. Commissioners negotiating it met at Mount Vernon, again. That 1958 agreement established the Potomac River Fisheries Commission, leading to coordinated management of oysters and other resources. Virginia's separate Fisheries Commission was renamed the Virginia Marine Resources Commission in 1968.

The state border affected oyster replenishment efforts as recently as 2018. Plans to replenish oyster shells in the Virginia side of Pocomoke Sound were delayed by concerns about cross-boarder poaching. Virginia sought to mitigate the risk of illegal harvest by installing large stones on the bed of the Chesapeake Bay blocking access to a permanent poaching-resistant sanctuary. Funding and permitting delays, and then the COVID-19 pandemic, delayed the installation of 7,500 tons of stone into 2021.13

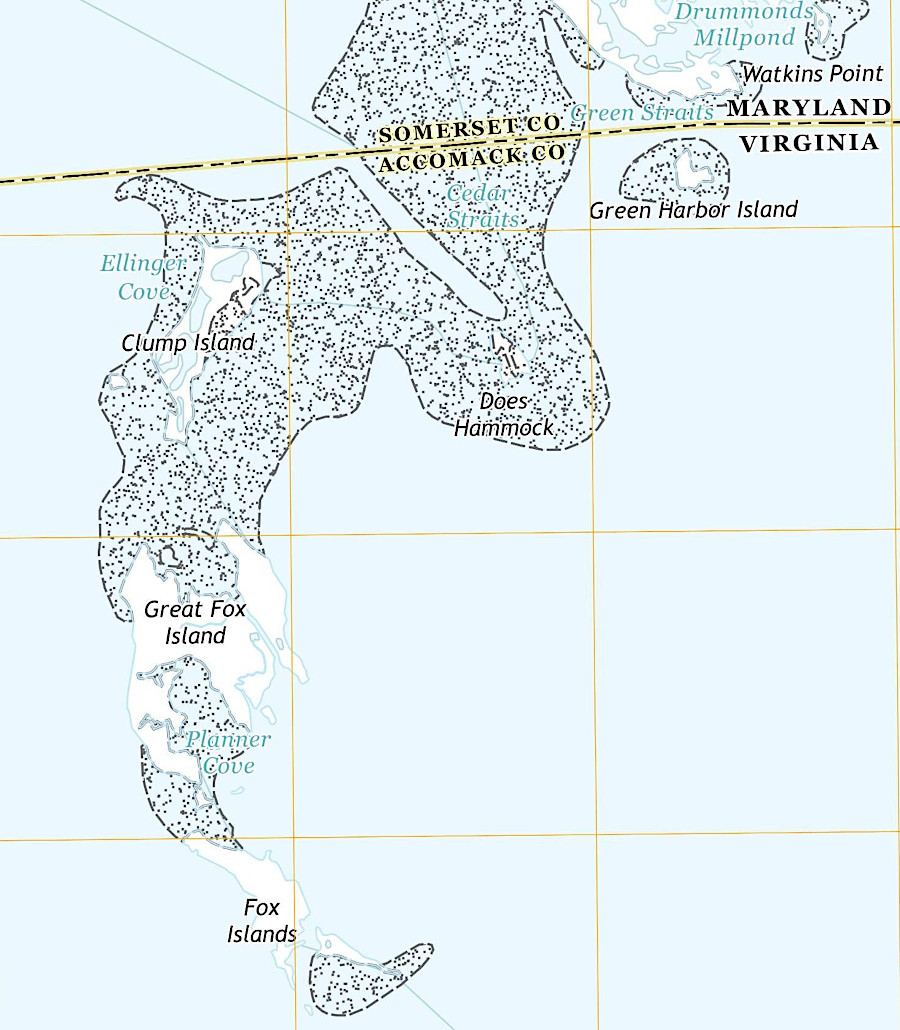

the 1877 Black-Jenkins arbitration placed the Fox Islands and their valuable oyster beds in Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Great Fox Island VA-MD (1:24,000 scale topographic map, 2016)

Watkins Point was still a mapped feature in 1735

Source: Library of Congress, Maps of the Maryland-Pennsylvania boundary used as trial exhibits in the 1735 court suit brought by the Penns against Lord Baltimore (by John Senex, c. 1735)

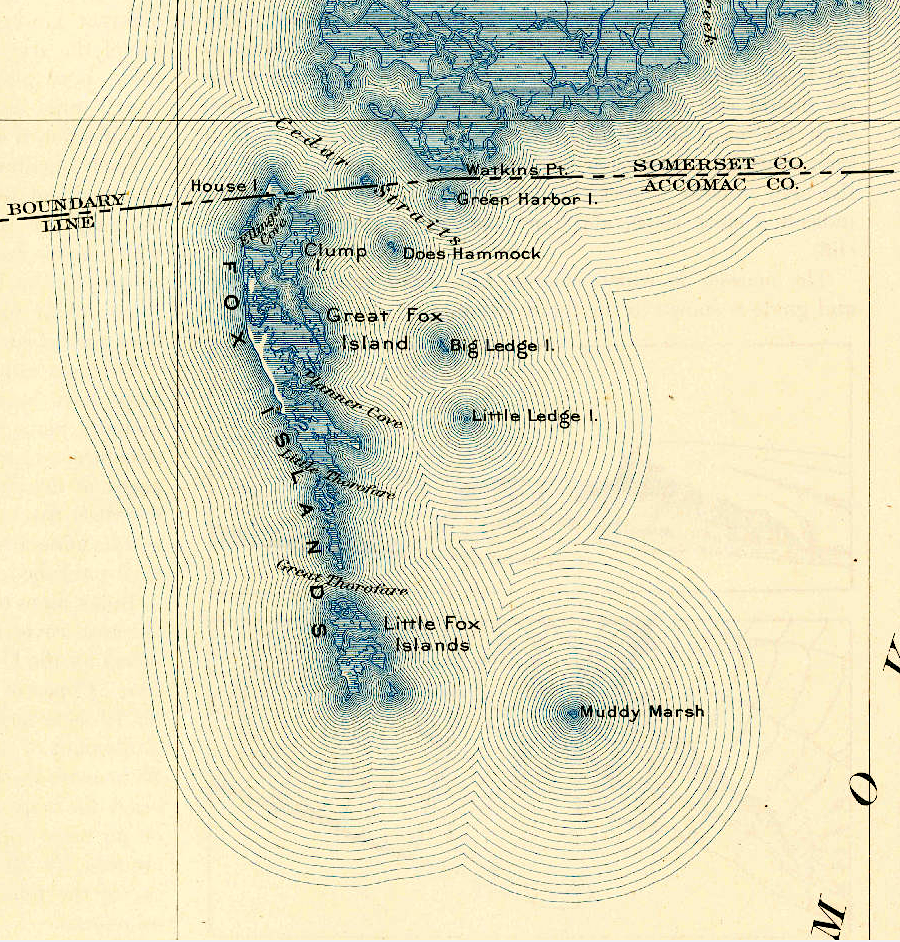

Fox Islands, south of the border in 1903

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Great Fox Island VA-MD (1:62.500 scale topographic map, 1903)