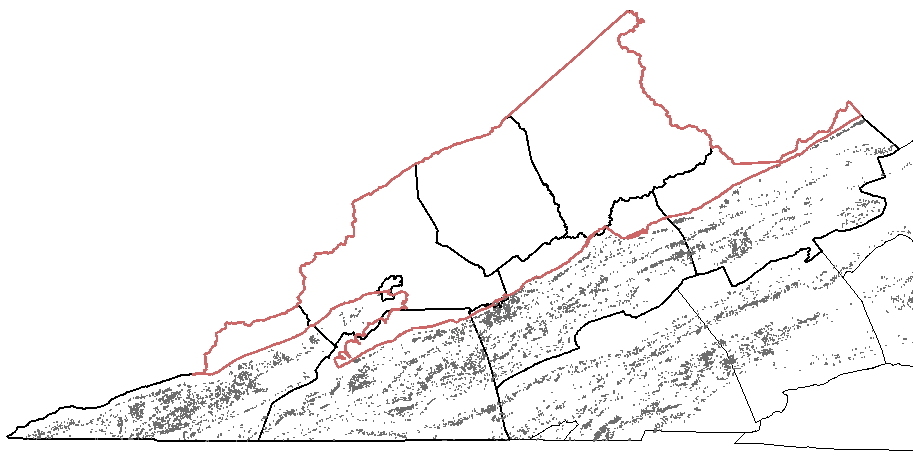

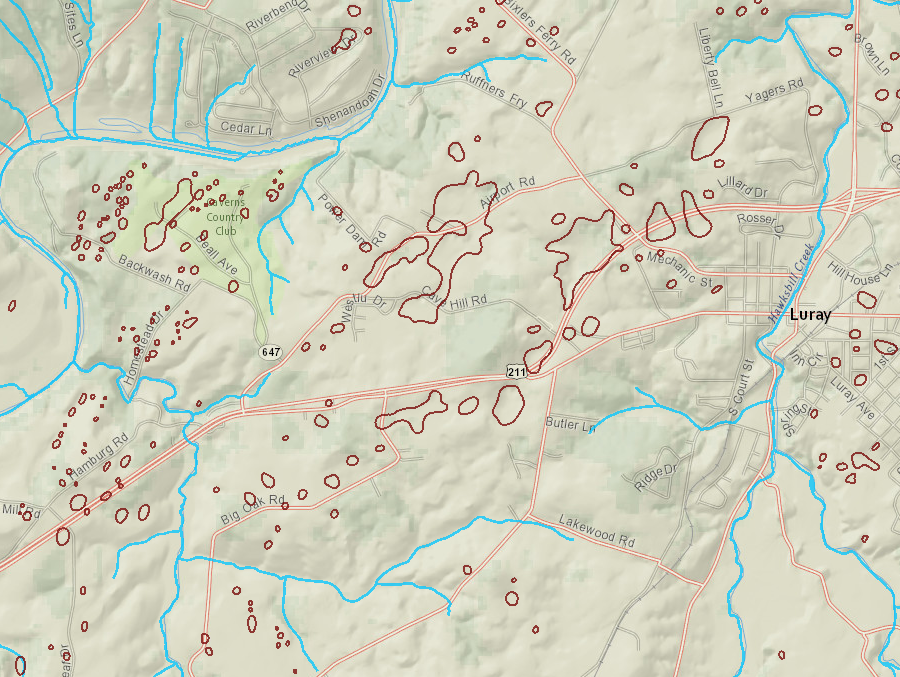

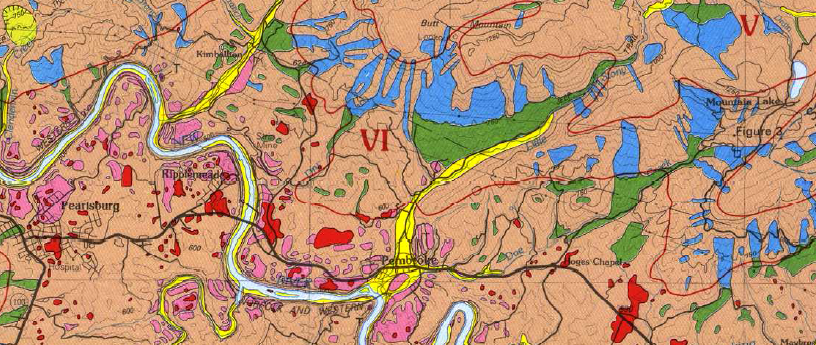

karst topography (in gray) is common in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, but absent on the Appalachian Plateau

Division of Geology and Mineral Resources (DGMR) Flexviewer page

karst topography (in gray) is common in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, but absent on the Appalachian Plateau

Division of Geology and Mineral Resources (DGMR) Flexviewer page

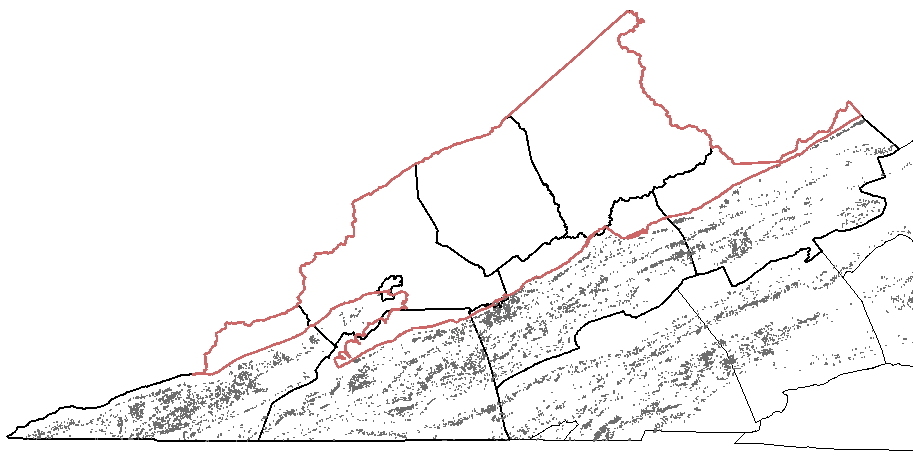

As the groundwater dissolves limestone, it creates voids and removes the rock that supports the surface. At the ground surface, sinkholes form where the ground has subsided underneath. Though sinkholes are most common in the limestone valleys west of the Blue Ridge, they are also found in the Coastal Plain.

Grafton Pond is a water-filled sinkhole owned by the City of Newport News. It formed in the fossil-rich Yorktown Formation, where calcium shells dissolved and the surface dropped to create a depression. Within Colonial National Historical Park, 8% of the land is karst where the topography reflects the dissolving of the bedrock.

In the 1781 Battle of Yorktown:1

sinkholes form in the Yorktown Formation when calcium shells dissolve

Source: Colonial National Historical Park, Geologic Resources Inventory Report (Figure 16)

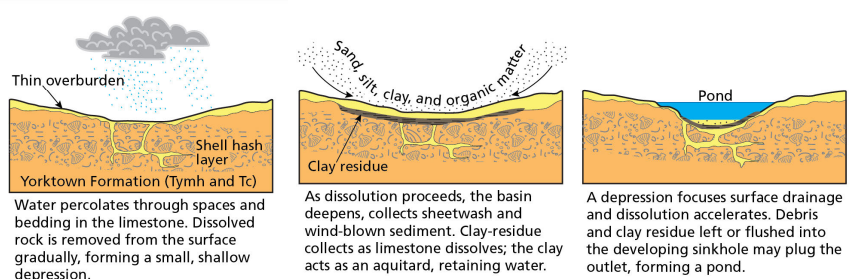

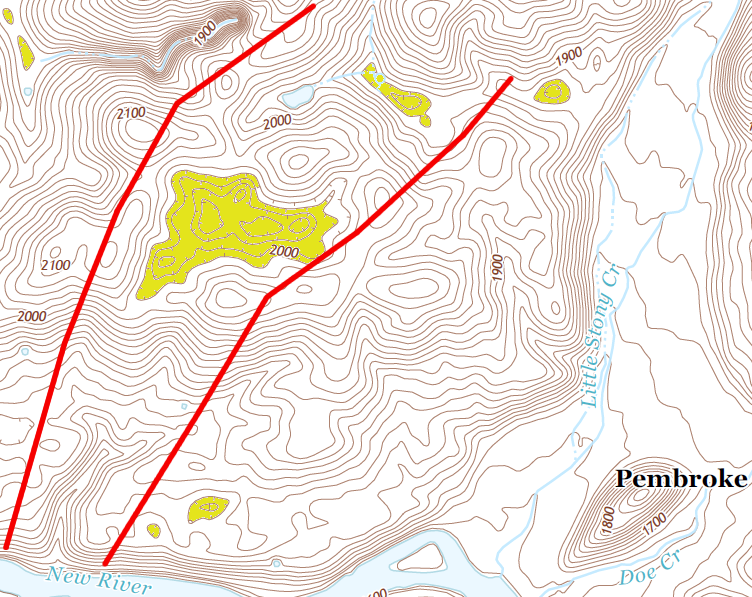

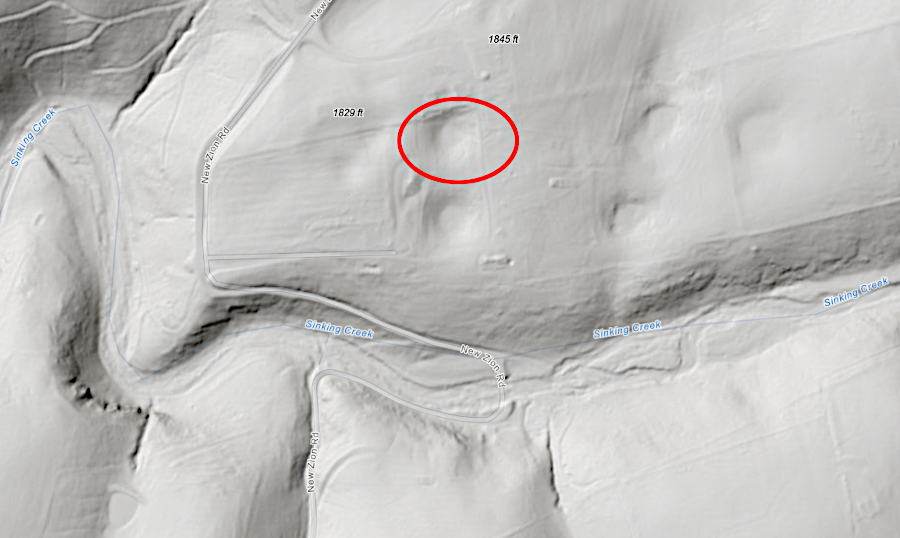

Some valleys have no "exit" where a stream leads to a river. Instead, the water drains into the sinkhole, enters the cave, and then exits the cave at a spring before reaching the river.

Luray Caverns is surrounded by sinkholes and karst landscape features

Source: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Virginia Natural Heritage Data Explorer

Some surface streams also lose water to a subsurface conduit, and can even appear to dry up before reaching a river. A classic "losing stream" is Sinking Creek in Giles County. Most of the water in the stream sinks underground about a mile before the stream reaches the New River, leaving a rocky streambed at the mouth of the creek that is filled with water only during storms.

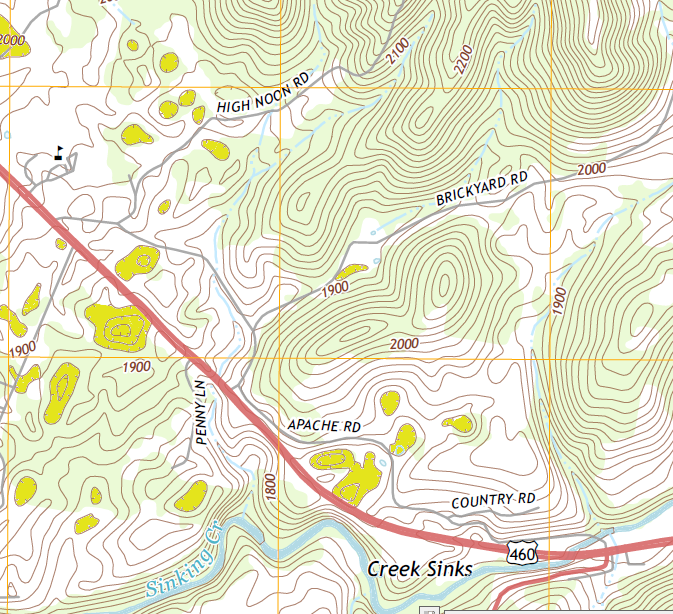

sinkholes (shaded yellow) are clear signs of karst topography - as are creeks that lose water underground and sink out of sight

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Eggleston 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013)

The term karst topography describes the landforms in a region with a large number of caves, sinkholes, and losing streams. USGS quad maps use hatched contour lines to indicate sinkholes, and cavers carefully explore karst areas in hopes of discovering an entrance to a previously-undiscovered cave.

karst topography (colored dark red) is common near Pembroke (Giles County)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Map showing surficial and generalized bedrock geology and accompanying side-looking airborne radar image of the Radford 30' X 60' quadrangle, Virginia and West Virginia

potential location of cave system with no surface opening, near Pembroke (Giles County)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Pearisburg 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013)

area in yellow indicates sinkholes, beneath which may lie an undiscovered cave system

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Pearisburg 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013)

Nearly all caves show signs of rockfalls from ceilings, and a cave room may grow so large that it collapses. Mother Nature does not excavate rooms according to the same engineering designs used by coal miners, leaving pillars to support the roof.

Natural Tunnel and Natural Bridge show what happens when just a portion of the roof collapses. Natural Chimneys was formed by erosion of the limestone ceiling and one side of a former cave.

The general rule is that limestone caves are located near the surface, in the top 1,000 feet. The acidic water is concentrated there. By the time the surface water reaches a deeper depth, it has been neutralized and is no longer able to dissolve calcium carbonate. In New Mexico, however, some very deep caves have been formed by acid fumes rising up from underground gas deposits, so there is an exception to every rule.

LIDAR imagery reveals how sinkholes have no streams exiting them; water drains underground instead

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, BETA: Virginia Geologic Map (2021)

Limestone in Loudoun County - rare location for karst topography east of the Blue Ridge

Source: "Loudoun County Limestone Map" in Loudoun County's Private Water Wells in Limestone Geology Regions: Frequently Asked Questions

Proposed Limestone Overlay District in Loudoun County - zoning controls based on geology

Source: Loudoun County Mapping System