canoes powered by muscle

Source: National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Photo Library

canoes powered by muscle

Source: National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Photo Library

The human muscles of Native Americans were the energy source for hunting, fishing, and farming in Virginia for thousands of years. For transportation, Native Americans in Virginia also used their muscles. They hauled items such as deer meat or skins on their backs, without the use of domesticated horses or even the wheel.

The muscles of the Native Americans were strong enough for paddling canoes substantial distances, including across the Chesapeake Bay to the Eastern Shore. Those canoes were not streamlined, so the effort required to paddle canoes loaded with grain and people must have been tiresome. However, the Virginia tribes lacked the knowledge for using wind power and sailing against the current.

After the Europeans arrived 400 years ago, human muscles remained the primary source of energy for farming. Indentured servants, small farmers working their own fields, and slaves on the larger plantations cleared the land, then planted, weeded, and harvested crops by hand.

If tobacco growing had not been energy-intensive, or if energy-saving technology such as modern John Deere tractors had been available in the 1600's, there would have been far less economic justification for importing slaves to Virginia.

ocean-going ships powered by wind, with longboats rowed to shore

Source: Library of Congress, 1492: An Ongoing Voyage

Wind power was the energy source for European ships that sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to reach colonial Virginia. The Europeans developed sailing technology and discovered the "New World" before the North Americans figured out how to sail to Europe.

Early European visitors and colonists also relied upon wind power for transportation up the rivers to the Fall Line. Sailing was far easier than paddling or rowing, especially when hauling heavy cargo, so long as the wind was blowing in the right direction or rivers were wide enough to tack back and forth.

When the wind was too light or the rivers too narrow, John Smith demonstrated the alternative - pull down the sails and have the sailors row, just as Native Americans rowed canoes.

small boat (shallop) used by John Smith to explore Chesapeake Bay in 1608

Source: National Park Service, Sidney King drawing

The European colonists also used the wind to power some manufacturing facilities. The first windmill in Virginia was built near modern-day Hopewell at Flowerdew Hundred, after that plantation was purchased by Abraham Peirsey and renamed Piersey's Hundred.1

Windmills also provided the energy for grinding the grain at Norfolk that fed the bakeries, which produced the flour and bread purchased by the ships that docked there. There were few hills or waterfalls at Norfolk, so wind power was more available than waterpower

a post windmill was built at Flowerdew Hundred for show rather than function, then relocated to American Wind Power Center in Lubbock, Texas in 2010

two names define the same place

Source: Geographic Names Information System (GNIS)

The value of wind power is still recognized in the area today. In the Chesapeake Bay and along the Atlantic Ocean shoreline, the wind near the ground is not blocked by trees/buildings or disrupted by hills/valleys.

Way back in April, 2001, a German-based energy company (ProVENTO) announced it would locate their headquarters at Cape Charles Sustainable Technology Park in Northampton County and build six 1.3-megawatt wind towers on the Eastern Shore.2

That project was never constructed. Proposals for creating electricity from modern windmills off the Virginia coast are still being discussed, along with proposals for windmills in Highland County and in the Blue Ridge to the south, but use of wind to generate electricity has been very slow to develop in Virginia. Not all places in the state are equally suitable:3

wind energy map of Virginia, at 50 meters above the ground

Source: Department of Energy -

Virginia Wind Resource Map

Wind can push sails and turn wheels, but it does not provide heat. The easiest way for early Virginians to get warm was to stand in the sun - but sunlight was not available 24 hours per day.

Native Americans used firewood as their primary energy source for heating their dwellings and cooking food, and for heating mud to make pottery. Cutting firewood with stone and bone tools would have been burdensome. Most Native American fires would have been fueled by branches that had already been brought down by natural processes, before being collected.

Europeans, with iron hatched and axes, could cut trees and split them for firewood. Firewood was also a fundamental energy source of energy for colonial manufacturing started by the Europeans. From the early glass factory at Jamestown to the iron furnaces of William Spotswood and Augustine Washington, the initial manufacturing facilities in the colony took advantage of the chemical energy in Virginia's extensive fuelwood resources. Once James watt developed a commercially-viable steam engine and sparked the Industrial Revolution, boilers could be fueled with firewood.

wood stove at colonial Governor's Palace (reconstructed) in Williamsburg

For most manufacturing sites, the European colonists tried to use waterpower. When redirected to a wheel, the mechanical energy in falling water could be used to grind grain, saw wood, or power bellows at an iron bloomery or forge. The home of the first large-scale ironworks in Virginia, Falling Creek, got its name because it is where a stream drops over the Fall Line and provides potential waterpower.

Throughout the colonial era, millers built dams across streams or dug ponds to ensure sufficient water during dry spells. A query of the US Geological Survey's Geographic Names Information System for Virginia places with "mill" in the name, and you'll find hundreds of locations...

Taylors Millpond in Greensville County, east of Interstate 95 where topographic relief is naturally low

Source: Microsoft Research Maps and US Geological Survey, Claresville quad (2013)

Water was delivered from where it was stored (millponds) to where it was used (mills), through artificial channels called millraces. The water from the millrace was controlled, so the miller could turn it on or off. Wheels would turn when the energy was needed to grind grain (corn or wheat) and limestone (plaster), or to power a saw to cut tree trunks into lumber.

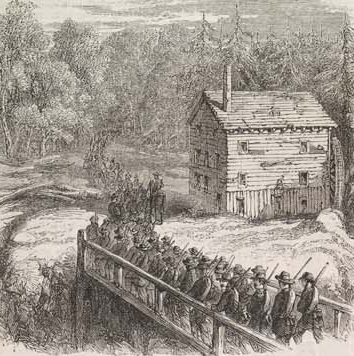

Arlington Mill on Holmes Run, near modern Lake Barcroft

Source: Illustrated London News, Franklin's Brigade Passing Arlington Mill on its Way to Occupy Munson's Hill (October 26, 1861)

Mechanical energy from a turning waterwheel was carried through the mill by a series of gears, axles, and pulleys to power grinding stones and saws. A well-balanced waterwheel could operate with the energy from just a small amount of water, perhaps no more than what we run today in the sink when we brush our teeth.

Burwell-Morgan Mill in Clarke County,

with water that has bypassed the waterwheel when the miller was not grinding

By the mid-1700's, mills were grinding corn and wheat on streams throughout Virginia, and cities began to emerge on the Fall Line. Topography shaped the location of these facilities - since falling water was the essential ingredient, mills were located adjacent to a stream. A mill located too close to a stream might be swept away in a flood, so millers built on nearby flat spots and dug channels ("mill races") from streams to their mills. "Merchant mills" ground grain for other farmers, but large farms also built private mills that served just one landowner. Merchant mills became a central gathering point for their community, with well-traveled roads leading to each facility.

By the mid-1700's, mills were grinding corn and wheat on streams throughout Virginia, and cities began to emerge on the Fall Line. Topography shaped the location of these facilities - since falling water was the essential ingredient, mills were located adjacent to a stream. A mill located too close to a stream might be swept away in a flood, so millers built on nearby flat spots and dug channels ("mill races") from streams to their mills. "Merchant mills" ground grain for other farmers, but large farms also built private mills that served just one landowner. Merchant mills became a central gathering point for their community, with well-traveled roads leading to each facility.

The textile industry in New England developed along the waterfalls of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. After the Civil War the industry moved south to take advantage of the low-cost labor as well as the reduced shipping costs for the main raw material, cotton. The textile production centers of Virginia in the last century (before textile manufacturing moved again at the end of the 20th Century to lower-cost areas such as Mexico, Southeast Asia, and China) were on rivers where waterpower could be used to spin the spindles to manufacture threads and cloth, as well as wash the materials and carry away the waste - Petersburg, Danville, even Fries on the New River (pronounced "freeze" in the winter and "fryze" in the summer).

The steam engine, powered by wood and later by coal, was a game-changing introduction of new technology. Steam engines allowed manufacturers to locate facilities away from rivers. Coal was popular for heating (as was wood), but coal-fired steam engines were used primarily for locomotives rather than as a source of energy for factories.

Coal was also used to create manufactured natural gas at "gas works" in urban areas. The synthetic gas, generated by heating coal in an oxygen-free oven, included methane, hydrogen, carbon monoxide, acetylene, and ethelyne. It was distributed through underground pipes and used for lighting streets and the interiors of homes. In Richmond, gas from coal was manufactured starting in 1851. Demand quickly outgrew the capacity to stockpile coal and heat it at the original site on Cary Street between 15th and 16th streets. A larger replacement facility in Fulton began operation in 1856. Even after natural gas pipelines reached Richmond in the 1950's, the Fulton Gas Works operated as a propane gas storage and transmission facility until floods from Hurrican Agnes caused too much damage in 1972.4

the original location of the gas works in Richmond between 15th and 16th streets was used for only five years, until a larger facility was constructed in Fulton in 1856

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Richmond, Virginia

Electricity transformed the development of Virginia, because it was the easiest form of energy to transfer from where it was generated to where it was used.

In the early 20th Century, cities on the Fall Line built dams (including Embrey Dam on the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg) to provide artificial waterfalls or to enhance natural ones. Water flowed through canals at dams, then dropped through mills near the dams. This harnessed the same source of energy that was initially trapped in small millponds. Starting in the 1880's, Virginia entrepreneurs built dams that turned turbines rather than waterwheels, and converted mechanical energy into electrical energy. Waterpower remains a key energy source today, though most Fall Line power plants generating electricity have been shut down and replaced by facilities closer to the mountains.

Electrical transmission lines enabled a dramatic increase in flexibility for locating the facilities that used that power source. No longer was it necessary to locate a factory next to the energy source, or even near a railroad that delivered coal. "Power-by-wire" can be transported to locations away from the waterfalls on the rivers, and even away from the cities.

Once electricity reached rural areas in the mid-1900's, companies could feel confident they would have access to energy if they locate facilities in virtually any part of Virginia. Today, almost every structure in North America (including many sheds and barns, even swimming pools in addition to houses, factories, and office buildings) is connected to every other structure through a network or "grid" of electrical wires.

Once electricity reached rural areas in the mid-1900's, companies could feel confident they would have access to energy if they locate facilities in virtually any part of Virginia. Today, almost every structure in North America (including many sheds and barns, even swimming pools in addition to houses, factories, and office buildings) is connected to every other structure through a network or "grid" of electrical wires.

Richmond was the first city in the United States to have electric streetcars. This started in 1888, using electricity created by a hydropower plant. Industrial facilities did not convert immediately to electricity, however. Factory owners had to amortize their investments in existing facilities before investing in new factories that could take advantage of new technology.

Existing factories slowly converted to use electricity, replacing complicated belt-and-pulley systems that once dictated where equipment could be located. Productivity increased especially fast as new factories were built, facilities designed to take advantage of the new flexibility where motors in the electrical equipment meant it could be moved anywhere in the building. Power lines snaked through the industrial sections of different cities, greatly expanding the number of parcels where a factory was now a cost-effective investment.

By making it possible to locate a factory anywhere in the country, electricity made it possible for rural residents to get high-paying manufacturing jobs. For much of the 20th Century, until globalization of trade changed the economic system, textile and furniture manufacturing plants provided high incomes to Virginia residents in rural areas such as Pulaski County and the small city of Galax.

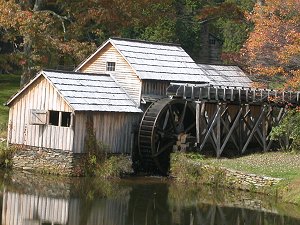

Today, energy is still generated by fuelwood in living room fireplaces and campfires on camping trips. Historic mills, such as Mabry Mill on the Blue Ridge Parkway and Colvin Run Mill in Fairfax County, use waterpower to grind grain for tourists. Hydroelectric plants of much-improved design still generate electricity from falling water. But three other sources supply the majority of energy to Virginians today - coal and nuclear power for electricity, and petroleum for the energy that powers our transportation system.

Quarles Mill on the North Anna River in 1864 included a dam that stockpiled water and also provided hydraulic head to generate energy for grinding grain/sawing lumber

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, A Triumph of the Wet Plate (p.42)

water of the South Anna River powered the stones that ground grain into flour at Yancey Mill (Louisa County)