the heritage of coal mining is dominant story in the Appalachian Plateau of Southwest Virginia, including Miners Park in Big Stone Gap

the heritage of coal mining is dominant story in the Appalachian Plateau of Southwest Virginia, including Miners Park in Big Stone Gap

The first settlers at Jamestown may have searched for gold, but the primary mineral wealth of Virginia was in the iron deposits until the Civil War.

In the Piedmont and the Shenandoah Valley, bloomeries and then iron furnaces provided an industrial component to the agricultural economy. Even the Coastal Plain had iron furnaces . Before 1622, an iron works was started at Falling Creek upstream from Jamestown. Governor Spotswood developed an iron plantation (rather than one based on tobacco) at Germanna, and George Washington's father Augustine managed an iron works in Stafford County just north of Fredericksburg. In the 1730's, both the Neabsco Iron Works on Neabsco Creek (near Potomac Mills) and a furnace/foundry at Occoquan were developed in Prince William County. They used water power from the streams to pump furnace bellows, and the Potomac River to ship the heavy product.

However, with the development in the early 1800's of more-efficient iron furnaces in Pennsylvania using coal and coke rather than charcoal for fuel, Virginia's iron mining and processing industry declined. Place names such as Catherine Furnace and Clifton Forge dot the map of Virginia, but the primary value of iron deposits in Virginia now is for paint pigment.

One mineral resource still shapes the economy and culture in southwestern Virginia. After the Civil War, Northern capitalists financed railroad expansion into the coal fields of West Virginia and Virginia. Coal Seam #3 at the Pocahontas Mine in Tazewell County was so thick, miners debated whether they preferred tall coal or short coal. Mining "tall" coal required reaching above your head - the seam was nearly 13 feet high in some places - whereas "short" coal involved back-wrenching stooping.

Map showing thickness of the Pocahontas No. 3 coal bed

Source: U.S. Geological Survey, A Digital Resource Model of the Lower Pennsylvanian Pocahontas No. 3 Coal Bed, Pottsville Group, Central Appalachian Basin Coal Region (Professional Paper 1625-C, Figure 5, p. H6)

After the railroad arrived in the 1880's, the Appalachian Plateau - especially Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise counties - shifted from subsidence agriculture to a cash economy based on lumbering and mineral extraction. Company towns were constructed and new employees recruited to man the deep mines (women were excluded from mining until recently). Mining communities grew up and shut down, based on the boom and bust cycles of the international energy markets. This population influx, and then the emigration when mines closed, altered the racial and social balance dramatically.

Due to the immigration of different cultural groups and the associated social disruption, more lynchings occurred in Southwest Virginia between the Civil War and World War I than in any other section of Virginia. The number of blacks in Southwest Virginia were much fewer than in Southside, and white Virginians in Tidewater and Southside were no more tolerant than the whites in the Southwest. The high number of lynchings in Southwest Virginia reflected the tension of new immigrants creating new rules of behavior in a new setting, in contrast to the well-understood social boundaries between whites and blacks further east.

When Virginia was given another Congressional seat after the 1870 Census, the Ninth District was created in southwestern Virginia. The "Fighting Ninth" was one of the few locations where Republicans were elected between Reconstruction and the 1970's. Virginia was so Democratic then that V. O. Key, in Southern Politics in State and Nation, called it a "museum of democracy" because elections were no longer competitive... except in the Ninth District.

As deep mining was replaced with surface mines, and as automation dramatically reduced the number of miners needed for every ton of coal produced, the number of miners in Southwest Virginia have dropped. The town of Pocahontas in Tazewell County is a ghost town compared to its size in the heyday of coal mining. Arson fires have destroyed the buildings that once housed thousands of miners, but it is clear to visitors today that the size of the town does not reflect the current number of jobs in the area.

Map showing overburden above the Pocahontas No. 3 coal bed (Note the shallow depth at Pocahontas, circled in Tazewell County)

Source: U.S. Geological Survey, A Digital Resource Model of the Lower Pennsylvanian Pocahontas No. 3 Coal Bed, Pottsville Group, Central Appalachian Basin Coal Region (Professional Paper 1625-C, Figure 33, p. H59)

Physically, Virginia's coal country has literally been reshaped by strip mining since the 1930's. The "overburden" of sandstone, shale, and limestone have been scraped away and dumped in nearby valleys, creating a new topography as well as a unique culture in southwestern Virginia. Restrictions on pollution now mitigate the effects, but the requirements to restoring mined areas to their approximate original contour do not apply if the entire mountaintop is removed.

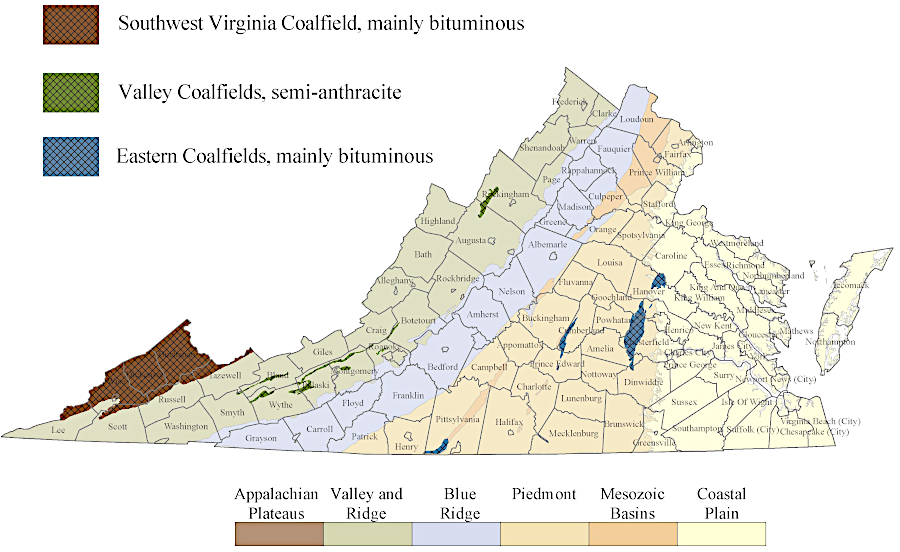

coal was mined in Triassic basins and the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, but Appalachian Plateau mines produced the greatest volume

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Cal