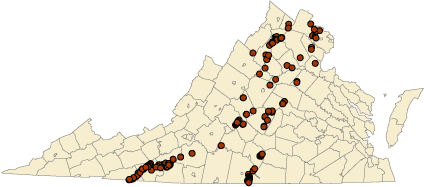

locations of copper ore in Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Copper

locations of copper ore in Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Copper

Copper is the oldest metal to have been processed by humans, who have extracted native copper from rocks for 10,000 years. The oldest copper pendant in the Middle East has been dated to 8,700 BCE.

For thousands of years, copper was the only metal being used by humans. Gold was first worked about 5,000 years ago, followed by silver and lead about 4,000 years ago.

Native Americans in North America were one of the first cultures in the world to mine copper and use it to produce tools. Around 7,500 BCE, during the Archaic Period before development of pottery and the bow-and-arrow, people living near the pure copper deposits in modern Wisconsin hammered native copper into spearpoints, awls, and other tools. The "Old Copper Culture" in North America may have made metal tools from native copper about the same time that smelting of copper ore emerged in the Middle East.

People of the Old Copper Culture stopped making metal tools around 3,400 BCE; thy used copper primarily for adornment after that time. The shift may have occurred because copper deposits around the Great Lakes produced a soft metal; impurities such as tin were not present to create strong natural alloys such as bronze. In the Archaic Period, stone tools were as effective as soft copper tools and required less effort to produce.

When climate change reduced food sources, most copper production was abandoned. Small copper awls for piercing hides were still valued as better than bone/stone equivalents, and shiny copper ornaments were still created as prestige goods.

stone ornaments were popular decorative items before European colonists brought copper

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Polished Stone Gorgets and Pendants

Copper was a prestige product highly valued by Native American leaders. When polished, it was one of the few shiny items in their world. Copper was traded from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, long before the arrival of European sailors and colonists created a new trade route coming from the east. Trade routes between the Mississippi River and the Southeast were in place at least 3,500 years ago, at the end of the Archaic Period. Archeologists have found Great Lakes copper in Georgia, placed in burial sites.1

When English colonists explored up the Roanoke River in 1585, they found people wearing copper ornaments. Thomas Hariot reported:2

English colonists in the 1580's discovered Native Americans in Carolina wearing copper as a shiny ornament

Source: Library of Congress, A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia (by Thomas Hariot, 1590)

However, there were no copper outcrops on the Coastal Plain. Travelers from the west had worn those ornaments on a visit to the Coastal Plain east of the Fall Line, or copper items had moved east via trade. The Native Americans that Hariot met even told him the source was not local:3

Despite the absence of copper deposits near the Atlantic Ocean coastline, archeologists have found evidence of copper residue in the workshop of the Roanoke colony's German metallurgist, Joachim Gans. The scientific report from the 1585 expedition to Roanoke Island claims discovery of iron and copper. It is possible that Gans may have acquired a copper ornament from one of the Native Americans who had acquired it through trade, and used that item in his smelting tests.4

Trade brought copper to the Coastal Plain of Virginia, just like trade brought copper to Roanoke Island. The Siouan-speaking Monacan tribe, which John Smith called the Manahoacs, occupied the territory in which Virginia copper is found. They may have scraped together small nuggets of native copper from the Blue Ridge, but their main source would have been through trade with people living closer to the Great Lakes.

Powhatan was paramount chief, with authority over much of the Coastal Plain in a territory called Tsenacommacah, but he had no local sources of copper. Desire for that prestige good made Powhatan dependent upon rivals living west of the Fall Line. The Algonquian-speaking tribes on the Coastal Plain traded regularly with the Siouan-speaking tribes on the Piedmont, despite the rivalry between the two groups. The Algonquian-speaking tribes living east of the Fall Line did not send trading expeditions directly to the Great Lakes.

Powhatan's access to copper changed dramatically in 1607. The English who settled at Jamestown provided a new source of copper. That may have been one reason Powhatan allowed the struggling community of "tassantassas" (strangers) to survive. He may have calculated that the English settlement on a low-value island, occupied by people unable to fish or grow enough corn to feed themselves, would not grow to become a threat - but continued trade with the English would eliminate Powhatan's need to acquire copper from the Monacan.

The English copper has a different set of trace elements than copper from the Great Lakes or the Blue Ridge. The distinct chemistry has allowed archeologists to identify sites where Native Americans had traded with Jamestown or seized European copper items in raids during the early 1600's.5

The colonists, particularly the sailors who traded with the Native Americans while ships waited to return home, created a massive increase in the copper supply. Trade routes that traditionally sent Atlantic Ocean shells inland across the Blue Ridge also transported copper items across the mountains, but now from east to west.

Native Americans in (modern) Montgomery County acquired copper in the Contact Period via from trade from the coastline

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Tubular Copper Beads

The copper brought from England had originated as ore in Central Europe north of the Alps, plus Scandinavia. In England, copper was pounded into flat sheets by water-driven battery hammers, then used to create products for domestic use. Edges of the sheets were cut off as waste when converting flat sheets into pots and other objects. When copper kettles were manufactured, waste was produced from straps, rims, and rivets.

Once the English realized that shiny, irregular pieces were valued by the Native Americans who used the copper as an ornament, off-cuts were shipped to Virginia as a trade item rather than returned to the smelter.

The Jamestown colonists sought to find copper, tin and zinc as well as gold, silver, diamonds and pearls. The First Charter of the Virginia Company reserved to King James I a one-fifteenth share (6.7%) of the value of any copper discovered in Virginia. Though the over 2,000 tons of "ore" brought back to England by Martin Frobisher's three voyages to Canada in l576-1578 had no valuable minerals, the colonists may have known that Samuel de Champlain had found copper on Nova Scotia in 1604.6

Investors in the Virginia Company also invested in England's copper monopolies. Celtic mines pre-dated arrival of the Romans, who may have sought access to the tin in Wales more than the copper. The Romans could obtain copper from Cyprus and Spain (the word "copper" is derived from "cyprium," or "metal of Cyprus"), but needed to add 10% tin to create the bronze alloy.

The Society of Mines Royal had a monopoly on mining copper in England, and the Society of Mineral and Battery Works had a monopoly on creating copper plate and mixing copper with zinc to make brass. However, the zinc ore available in England included a high percentage of lead, resulting in low-quality brass alloys and low demand for mining England's copper ore.

Investors in the Virginia Company were also investors in the copper monopolies; finding high-quality ore in Virginia could generate a return-on-investment through multiple companies. Chemistry experiments at Jamestown included mixing copper scrap from England with local Virginia rock, hoping to find tin or zinc with low quantities of lead or other impurities in order to manufacture bronze or brass.

Archeologists at Jamestown have found evidence that metallurgists there were experimenting with copper alloys during the earliest days of colonial settlement, though there are few references in the written records of such work. The colonists may have been smelting English copper with rocks and sediments found in Virginia in hope of discovering zinc, then manufacturing brass without alerting the guilds which had monopolies in England.

The industrial research at Jamestown was disappointing. Until the 1800's, only iron ore was discovered in commercial quantities within Virginia.7

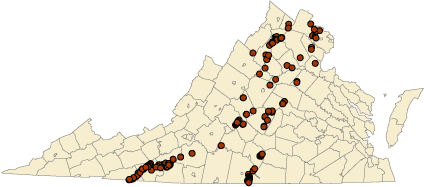

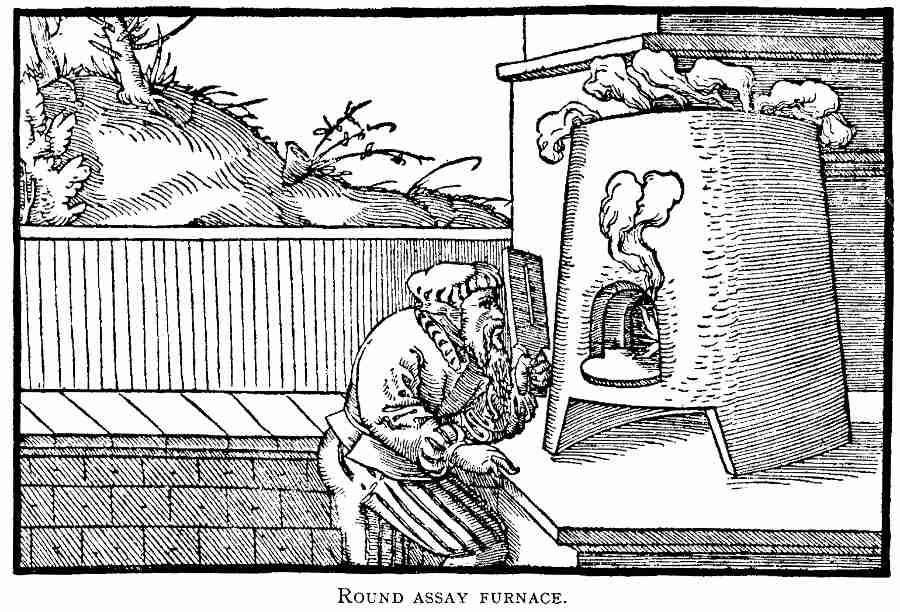

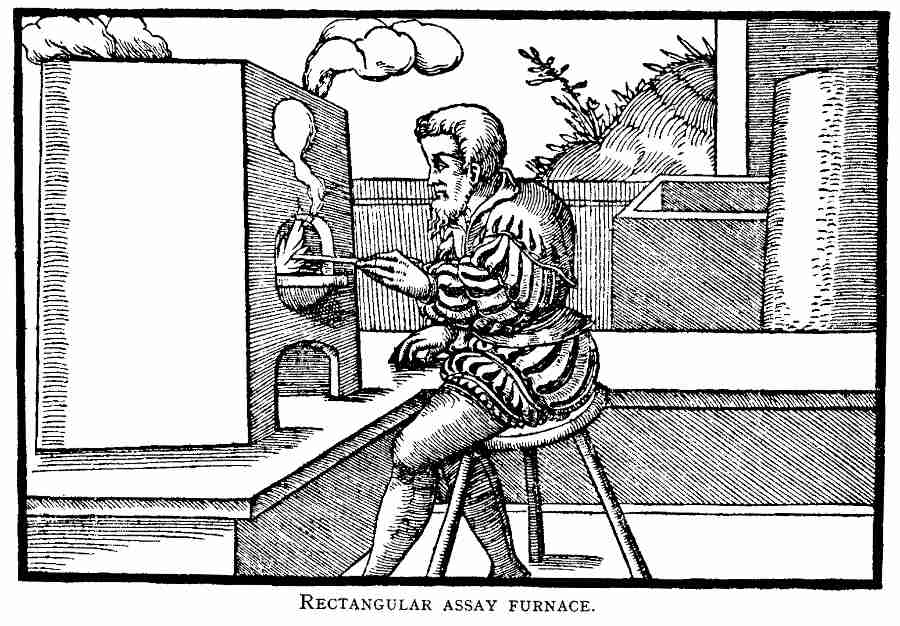

the technology used at Jamestown for smelting ore was based on experience from Central Europe

Source: Georgius Agricola, De Re Metallica (p.223)

The English who settled at Jamestown in 1607 were slow to explore lands outside the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Explorations going southwest of the Appomattox River were considered, but the uprisings in 1622 and 1644 delayed them. In a 1647 letter, a visitor to Virginia reported that copper was produced near the Roanoke River:8

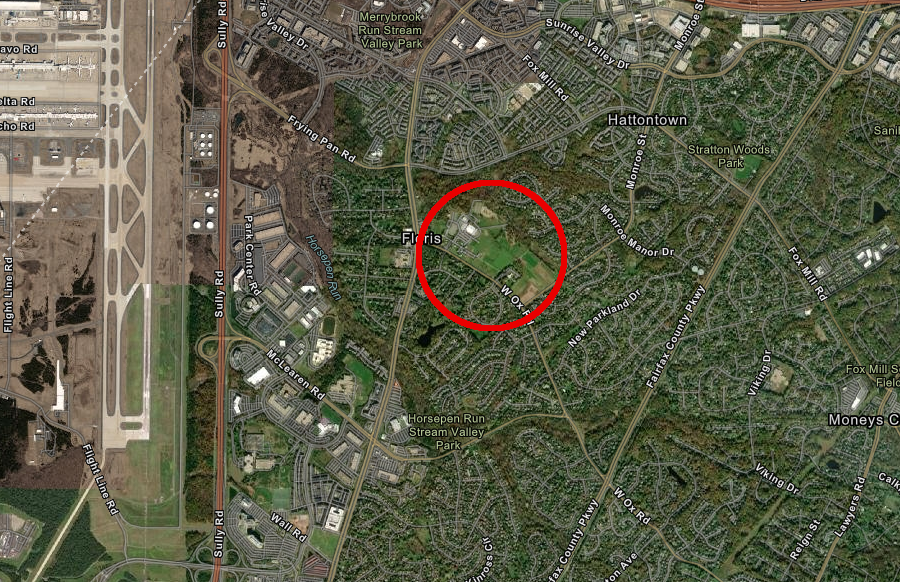

The first copper mine in Virginia was near modern-day Dulles International Airport. Robert "King" Carter organized the Frying Pan Copper Mining Company in 1728 to mine ore on Frying Pan Branch, which at the time was part of Stafford County. Carter was the land agent for Lord Fairfax and controlled the "proprietary" land grant between the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers. He issued a grant for 762 acres to his sons, but in fact "King" Carter controlled the operation. He ultimately issued grants for 20,000 acres for potential copper development.

Carter shipped slightly over 100 pounds of unprocessed ore to England in 1729. If the assay of that ore indicated it was sufficiently enriched in copper, Carter was already wealthy enough to finance the labor necessary to develop a mine.

On lands outside the Fairfax Land Grant, King George I did not claim a percentage of any copper that might be mined. However, Lord Fairfax had indicated he wished to reserve one-third of the revenue from lead, copper, tin, coal, and iron mines.

Carter wrote him to highlight that previous land agents had not specified such reservations when they issued patents for land grants. Carter emphasized that enforcing such a provision would be a major deterrent, stopping anyone who might be willing to invest in developing mineral resources within the boundaries of Fairfax's grant. Carter's relationship with Lord Fairfax enabled him to proceed without worrying if a significant percentage of any mineral-related revenue from his Frying Pan prospect would have to go to the proprietor.

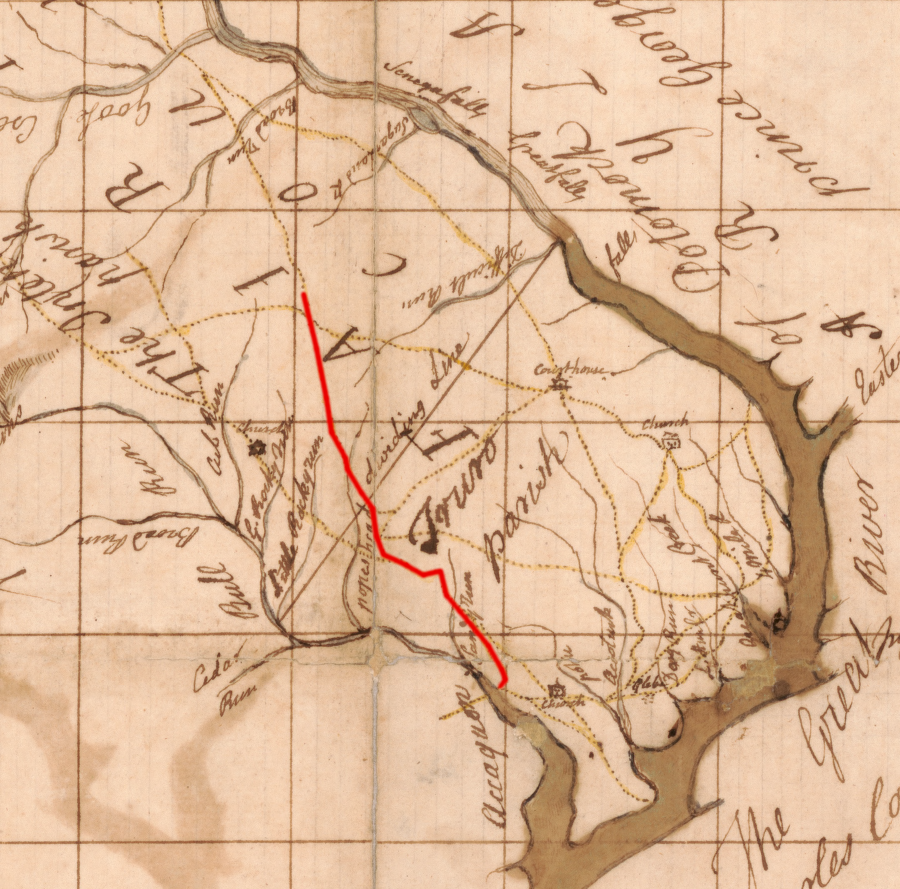

Thomas Lee, a rival of Robert Carter, controlled the shoreline along the Virginia side of the Potomac River. Rather than try to transport the copper through Lee's property, Carter built a new road to haul wagons loaded with ore south to a new Copper Mine Landing on the Occoquan River. That landing was probably near Colchester, just downstream of the current town of Occoquan.

Copper Mine Landing was across the river from the first Prince William County courthouse at Woodbridge. That courthouse was built after Princ William County was carved out of Stafford County in 1731. Between 1731-1742, when Fairfax County was created, legal dealings regarding the land along Frying Pan Branch were processed by the local Prince William County court.

The historic wagon road became known in Fairfax County as Ox Road. Tired pack animals were replaced with fresh ones halfway through the trip. The Half Way House was located just south of the modern Fairfax campus of George Mason University.

Virginia's first copper mine was at or near modern Frying Pan Park in Fairfax County

Source: ESRI, ArcGis Online

Robert Carter had his agents in England hire some skilled miners, men capable of recognizing the difference between valuable ore vs. worthless rock, and send them to Virginia. The skilled miners were unhappy with working conditions, complaining that food provided to them lacked fresh meat and traditional work-free holidays were not being recognized.

In 1731 the miners discovered what they considered to be a rich vein and four tons were shipped to England. By the end of the summer, however, the deposit had been exhausted. There was just a thin "skin" of copper deposited by hydrothermal fluids, during or after the time volcanic dikes/sills metamorphosed sediments.

Further digging nearby, and extending the old shafts deeper to the water table, did not reveal any additional veins. After Robert "King" Carter died in 1732, the mine was abandoned.9

Ox Road (red) was constructed by King Carter around 1730 to haul copper ore to the Occoquan River

Source: Library of Congress, A plan of the county of Fairfax on Potomack River the middle of which is in 39⁰, 12ʹ No. latitude (by Daniel Jenings, 1748?)

When William Byrd II surveyed the Virginia-North carolina border in 1728, he discovered several copper miners west of the Fall Line between the Meherrin and Roanoke rivers in what would become the Virgilina mining district of the Carolina Slate Belt/Carolina Terrane. Byrd examined one mine that was at:10

Prospectors found multiple locations with malachite stains on quartz veins, but digging pits rarely revealed ore deposits worth developing. The most promising seen by William Byrd II was Cargill's mine. In 1730, it sent 3,000 pounds thought to contain copper to England for further processing. Byrd reported it "seemed full of metal," and:11

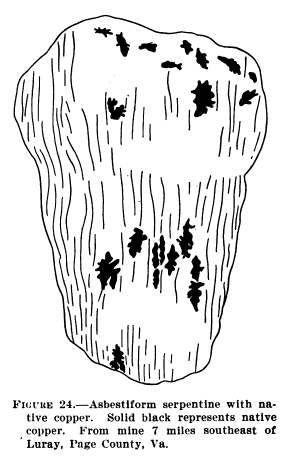

Native copper may have been present in the ore examined by William Byrd II. Virginia does have small lenses of native copper deposits in the Blue Ridge. Three mines have extracted significant amounts of native copper - the Dark Hollow mine in Madison County, the Hightop mine in Greene County, and the Allen mine in Nelson County.

Otherwise, copper has been produced in Virginia as a secondary product together with other minerals present in an ore deposit.

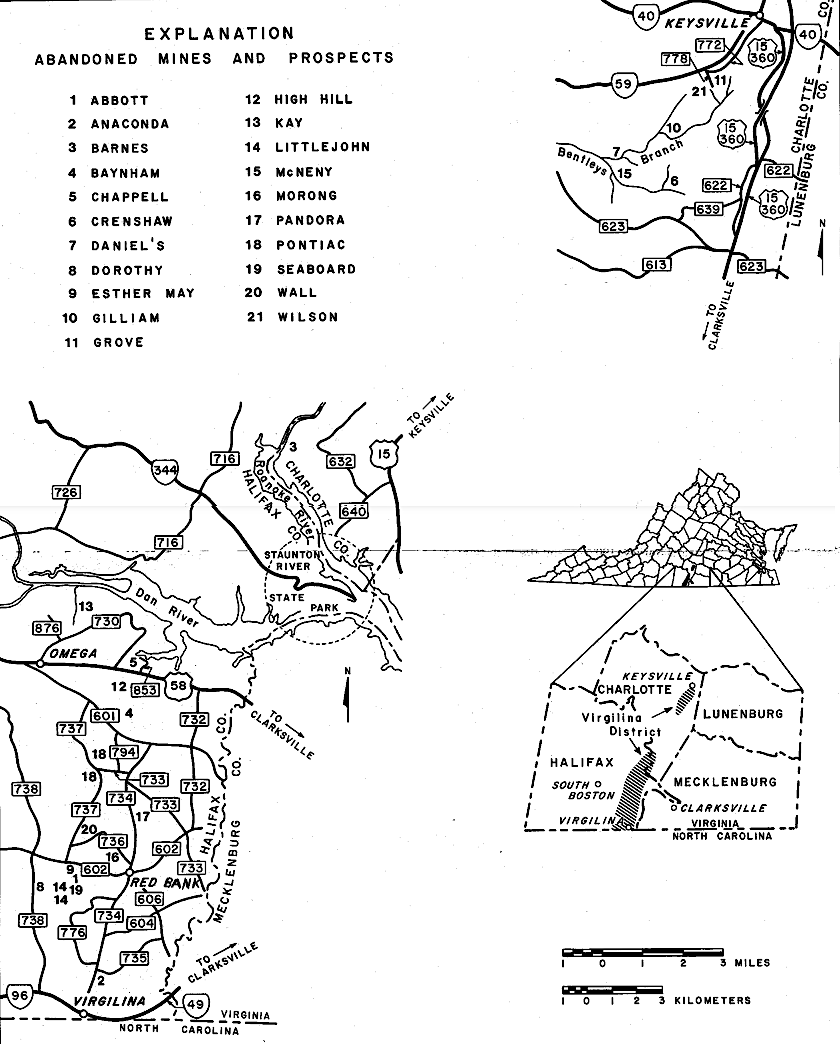

The Barnes Mine in Charlotte County on the Roanoke/Staunton River, upstream of the confluence with the Dan River, may have shipped copper ore to England before 1750. Over time other mines in andesite and andesitic tuff sections in the Virgilina District produced an estimated 750,000 pounds of copper.

A shaft 250' feet deep and another 350' deep were dug at the High Hill mine in Halifax County, which operated between 1899-1904. It reportedly produced 600,000 pounds of copper in the short period of active work, outside of later explorations which never resulted in reopening the mine. At the Seaboard Mine, also in Halifax County, one shaft was dug down 250' and two shafts exceeded 100' in depth. In the Virginia portion of the Virgilina District, milling facilities to concentrate copper ore were built at only the High Hill and the Seaboard mines.

The last commercial extraction of copper was at the Toncrae Mine in Floyd County, with production ceasing in 1947.13

locations of abandoned copper mines and prospects in the Virgilina district

Source: Virginia Minerals, Abandoned Copper Mines and Prospects in the Virgilina District, Virginia (Figure 1)

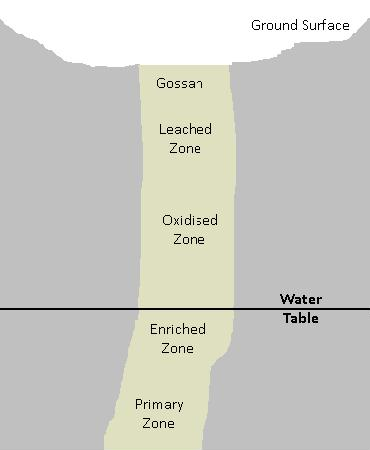

The copper ore found near the surface in the Piedmont in the 1700's may have included chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), the same mineral being smelted in England and later mined at Ducktown, Tennessee. Below the water table and saprolite zone, roughly 250 feet deep, the copper was still chemically bound to the sulfur in a sulfide ore such as chalcopyrite and bornite.

Near the surface, some of the copper had oxidized. That may have occurred during transport via hydrothermal fluids from the site of initial crystallization from magma in the island arc, or during later tectonic orogenies. Plutons in the Carolina Terrane date to 300 million years ago, and their emplacement could have triggered flow of hydrothermal fluids transporting copper.

Copper oxides such as malachite are easier to smelt. However, as Robert Carter discovered at Frying Pan, in Virginia the occasional pockets of oxidized ore concentrated by erosion and deposition were small. According to one assessment:12

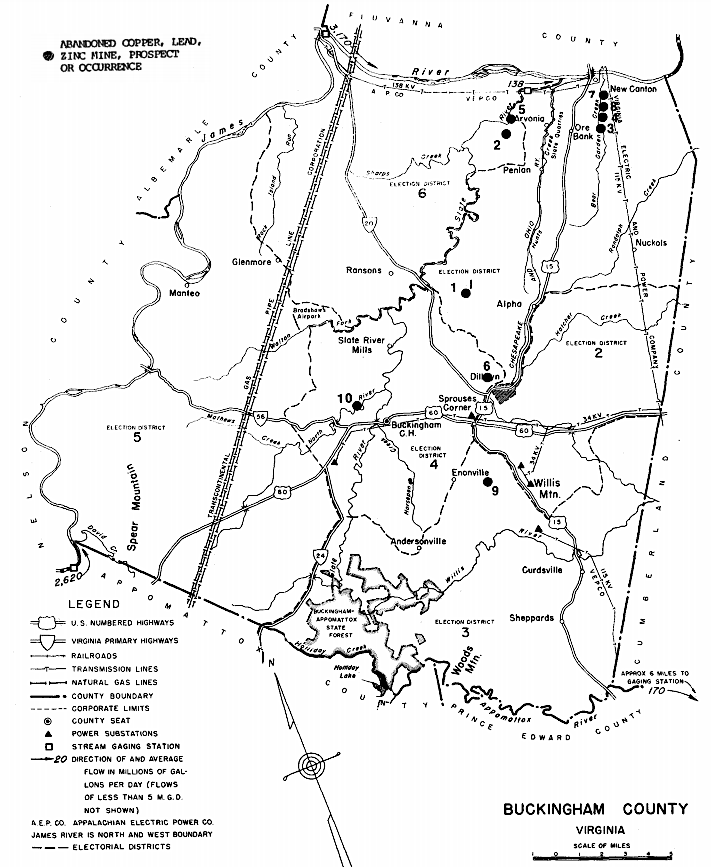

Mineral exploration after 1995 identified a region near Lynchburg with copper-zinc-lead-silver (Cu-Zn-Pb-Ag deposits) sulfide deposits that were potentially worth mining. To date, the commercial interest has been elsewhere, on prospective development of gold deposits in Buckingham County that may have been emplaced with the same terrane.

Nine core holes drilled into the sulfide deposits identified "disseminated, vein-type, and massive base metal mineralization." One drilled core identified 2.77% copper in a zone 16 feet wide, and another with 1.17% copper in a zone over seven feet wide. The copper is present, but not economically valuable under current market conditions.14

Near Lynchburg, there are copper deposits in the Alligator Back Metamorphic Suite. It was deposited in the Precambrian when Rodinia began to break up and great rift valleys formed. That particular tectonic splitting stopped before the supercontinent broke up, and the valleys filled with sediments. On what today is the eastern edge of the Blue Ridge, copper crystallized into ore deposits:15

Copper deposits in the Blue Ridge were created during the late Precambrian. Metals such as copper, cobalt, tellurium, and platinum may escape the upper mantle at scattered locations from a zone around about 15 miles deep with temperatures around 1000°C. In those locations, magma can migrate upward into the crust and bring molten metals that cool and crystallize as ore deposits.

Separation of different minerals in molten igneous intrusions and during metamorphism create concentrations of metals, forming lenses of sulfides of lead, zinc, iron and copper. Feeder dikes that brought Catoctin basalt to the surface also brought copper.

The Virgilina district in Halifax and Charlotte counties was once an offshore island arc, until the "Carolina Slate Belt" was accreted to the North American tectonic plate:16

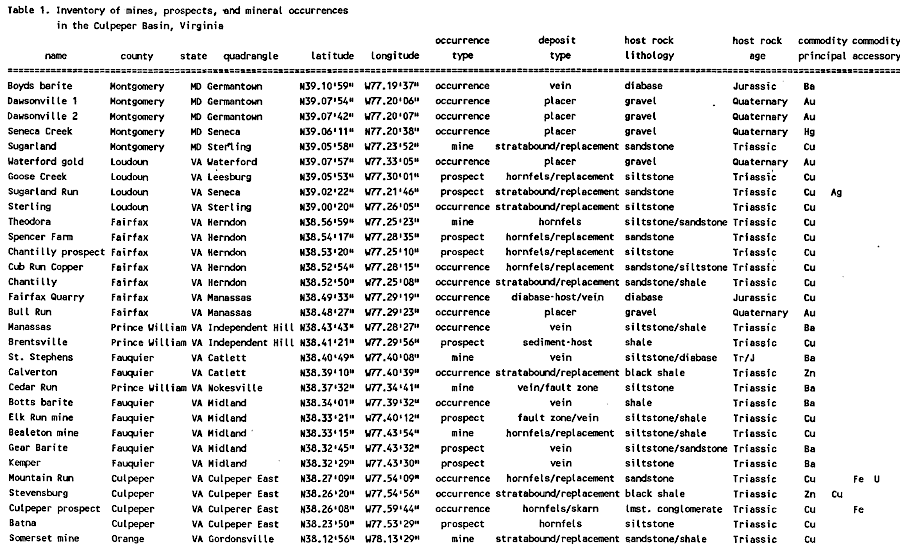

Copper deposits in the Triassic basins are much younger. They formed around 200 million years ago, as Pangea split up. Sediments that washed into Triassic basins included minerals such as iron and copper, plus enough sulfur to create acidic conditions. In some places, minerals were leached by acidic groundwater from rocks exposed near the surface, then carried to a depth where oxygen was not available. Upon reaching a "reduced" environment at the water table, minerals precipitated out of the groundwater. That leaching process concentrated minerals into an enriched deposit valuable enough to mine, while also creating a valuable "gossan" deposit of hard-to-dissolve iron minerals at the surface.

copper was dissolved by acidic groundwater, then redeposited at the water table to create concentrated ores worth mining

Source: Wikipedia, Supergene geology)

Robert Carter's mine in the Culpeper basin was a shallow deposit, suggesting it was formed by leaching and enrichment near the surface. As Pangea split and basaltic dikes/sills intruded as the Triassic Basin formed, the sandstone/siltstone sediments were baked into hornfels. Copper In most gossan locations, copper was concentrated in the upper 50-60 feet of the dikes. At the Gooney-Manor mine in Warren County, the shaft was dug 350 feet deep.

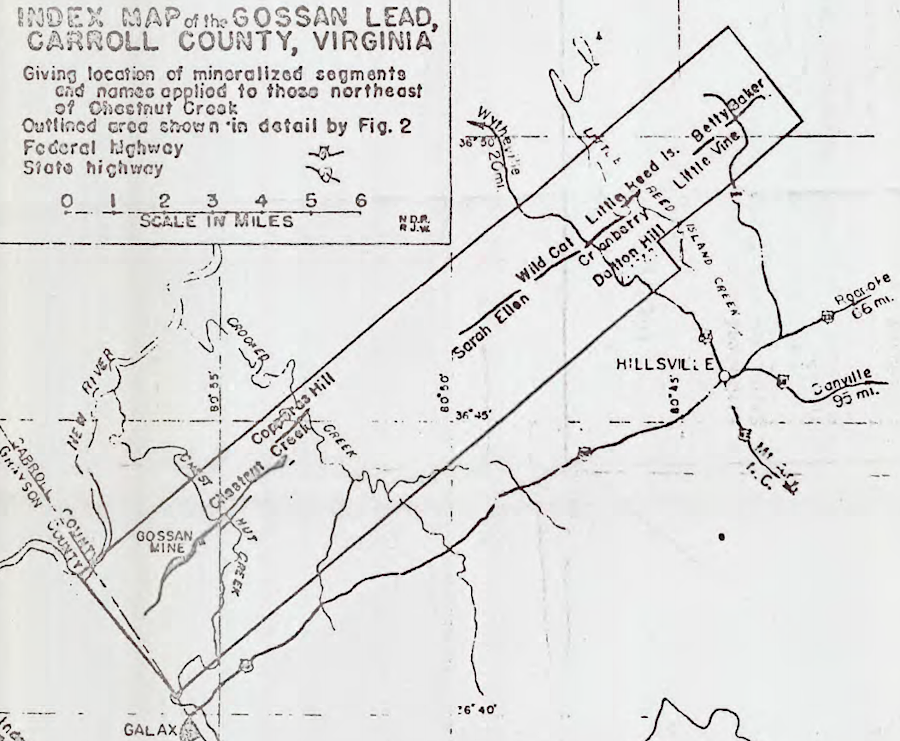

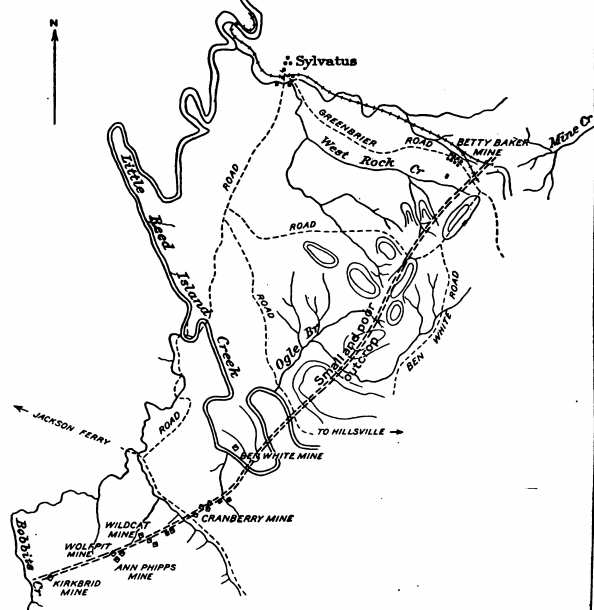

Copper was mined at the "Gossan Lead" in Carroll County until 1859. The primary ore there was about 0.5-0.7% copper, but near the surface copper sulfide had been converted to copper sulphate and transported down by groundwater to a secondary mineralized zone. The ore mined before the Civil War had 14% copper.

Within Triassic basins, some mineralization was due to hot hydrothermal fluids. Where the crust was stretched and thinned, basalt moved up to near the surface where it cooled into dikes and sills. Brines moving with the basalt were enriched in copper and other minerals. The sulfur-rich brines were heated, but it appears temperatures were cooler than 150°C. After the hydrothermal fluids cooled, minerals precipitated and solidified in sandstones and siltstones. Roots and other organic material (or basalt/hornfels) created a reducing rather than oxidizing environment that facilitated precipitation:17

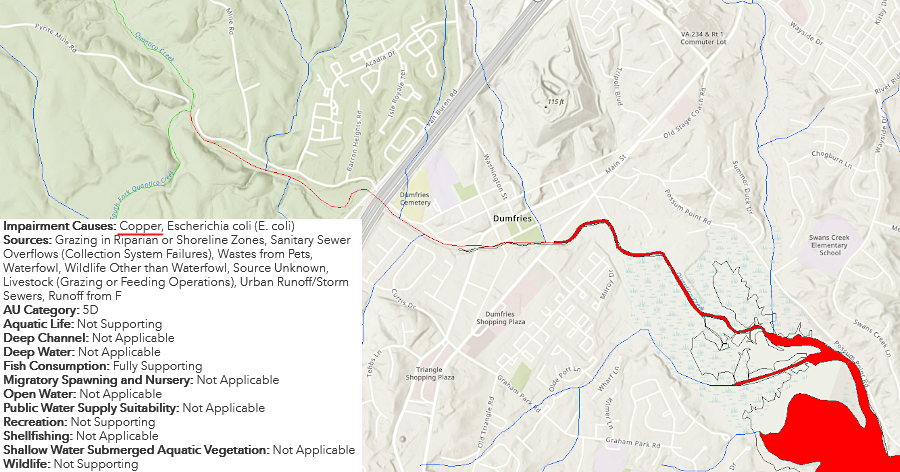

Hot hydrothermal fluids also created mineral deposits in the Piedmont terranes when they were island arcs, and during metamorphism as the terranes were accreted to the edge of Laurentia to create Pangea. Pyrite, gold, zinc, and copper deposits were formed where fluids flowed into faults and then crystallized. A pyrite mine operated on Quantico Creek in Prince William County between 1889-1920, and its tailings created acid mine runoff that polluted the creek for 75 years.

Even after reclamation of the site in the 1990's covered the tailings with lime and soil, there is still an excessive amount of dissolved copper contaminating the creek. The 2020 305(b)/303(d) Water Quality Assessment Integrated Report, the "Dirty Waters List" issued every two years by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), listed Quantico Creek as "impaired" in part because of the copper.18

copper is one cause of Quantico Creek being listed as impaired in Virginia's Dirty Water List

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Environmental Data Mapper

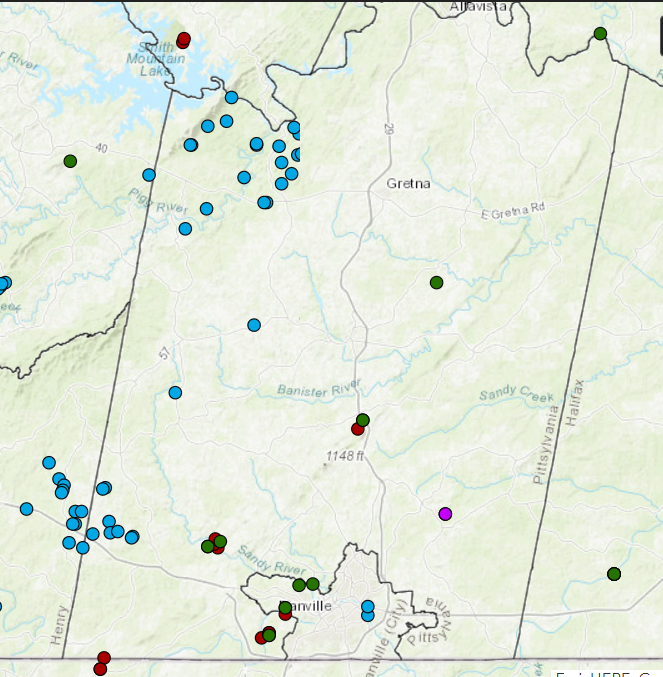

New exploration drilling for the Mountain Base Metals Project began in Pittsylvania County in 2021. A Canadian company, Aston Bay Holdings, drilled to 1,000 feet deep to determine the commercial potential of a copper and zinc deposit.

The same company was drilling for gold in Buckingham County, creating concerns that a large open pit mine might be developed. Opponents of metal mining operations organized initially around the gold mining proposal, In 2021 the Virginia General Assembly passed HB 2213, which directed the Virginia Department of Energy to study the potential health, safety and environmental impacts of gold mining.

the Press Pause Coalition highlighted a potential threat to drinking water from mining sites

Source: Press Pause Coalition, Surface and Groundwater Intake

The opponents of the gold mining organized the Press Pause Coalition. They expressed concerns that impacts of an open pit copper mine would be comparable to open pit gold or uranium mining, with a risk that sulfur and heavy metals might be carried in a heavy storm from the tailings into surface streams used as drinking water supplies.

An Aston Bay Holdings official stated that no open pit was planned. If the gold and copper/zinc deposits were commercially viable, he said the mining would be done through underground shafts and adits.19

One major source of "new" copper in Virginia could come from recycling efforts, or even mining of old landfills. The shift to electric vehicles (EV's) will increase demand faster than existing or new mines could increase supply:20

active and abandoned mines and quarries in Pittsylvania County in 2021

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Mineral Mining

Buckingham County has been extensively investigated for mineral resources

Source: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources, https://www.dmme.virginia.gov/commerce/ProductDetails.aspx?productID=2253 (Publication 93)

copper and other mineral deposits in the Culpeper Basin are associated with hydrothermal fluids generated by igneous/metamorphic intrusions and basalt dikes

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Base- and precious-metal occurrences in the Culpeper basin, northern Virginia (Open-File Report 87-252)

the Gossan Lead in Carroll County had 14% copper ore

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), The Gossan Lead, Carroll County, Virginia (Figure 1)

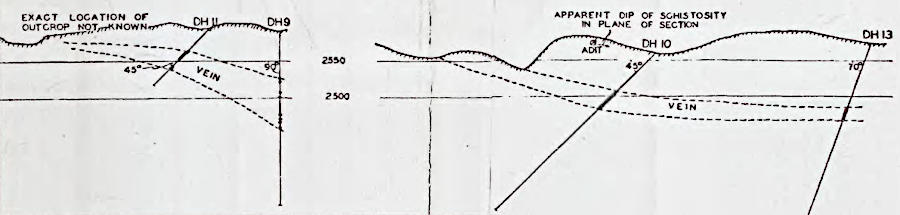

the vein of copper-rich ore at Gossan Lead in Carroll County was below the iron-rich gossan layer on the surface

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), The Gossan Lead, Carroll County, Virginia (Figure 3)

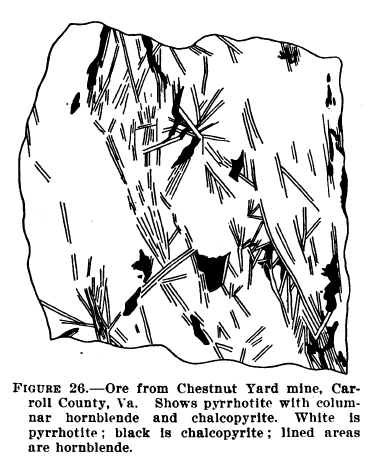

copper deposits in the Blue Ridge are associated with different types of ore

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Copper Deposits of the United States (p.111)

copper ore mined in Floyd, Carroll, and Grayson counties in the 1850's was shipped to Baltimore

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Copper Deposits of the United States (p.115)

copper ore was found with the Great Gossan lead deposit in Southwest Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Copper Deposits of the United States (p.117)