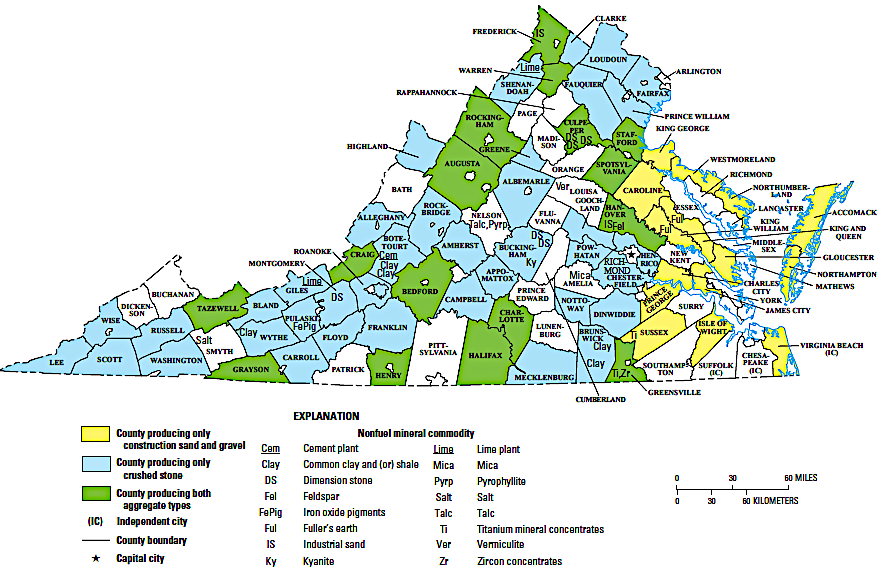

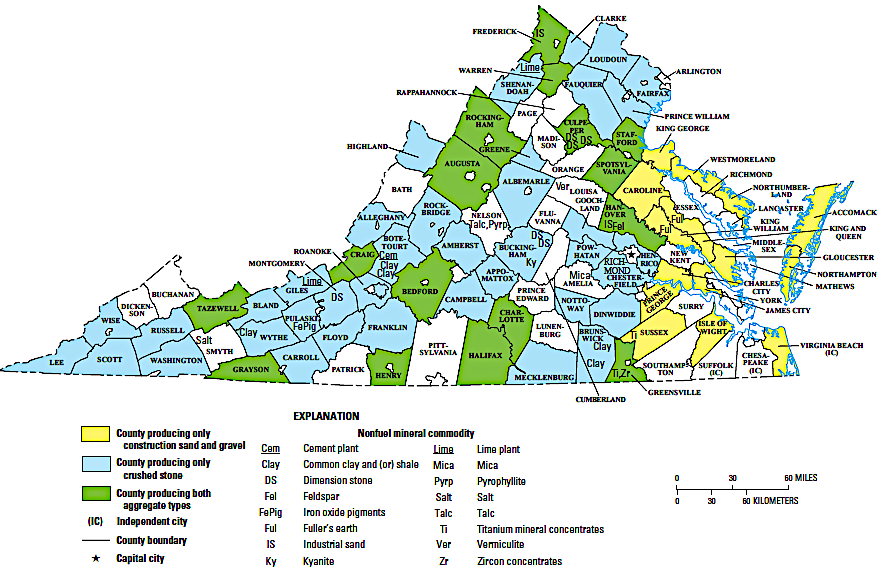

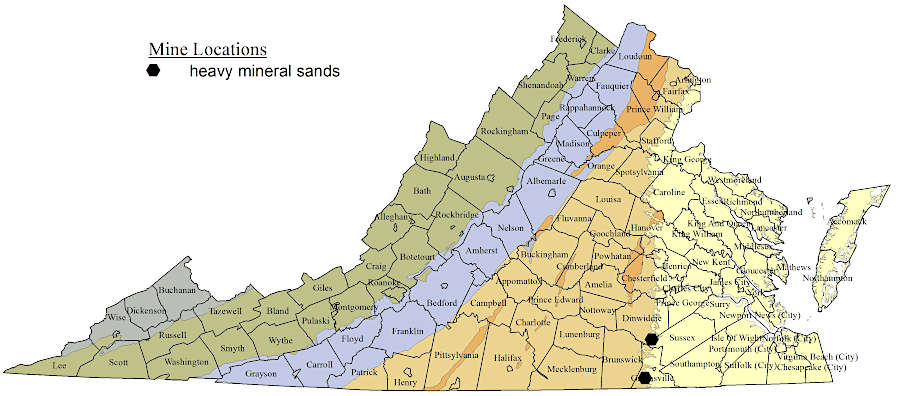

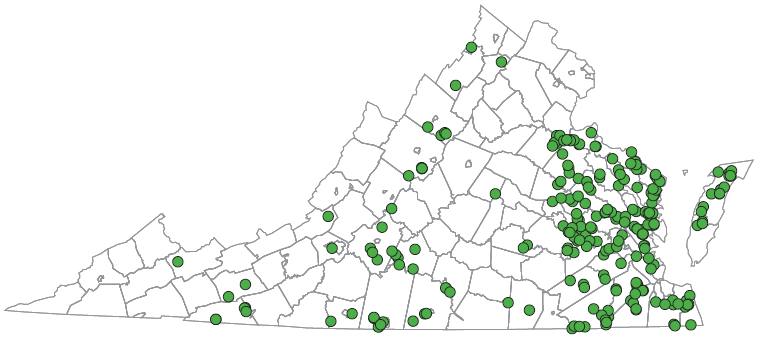

major nonfuel-mineral-producing areas in Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey, The Mineral Industry of Virginia (2014 Minerals Yearbook)

major nonfuel-mineral-producing areas in Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey, The Mineral Industry of Virginia (2014 Minerals Yearbook)

Each mineral has a distinct arrangement of atoms from its component elements, so each mineral has different properties. Laboratory experiments suggest there are over 500,000 possible combinations of the elements found on earth.

A total of perhaps 10,000 minerals may be found naturally on earth, but so far less than 5,600 have been identified from 300,000 localities around the world by the International Mineralogical Association. The number of known minerals grew by 25% after 2000, as scientists used new technology to analyze crystal structures and complex mathematics to predict how minerals could have formed.

As conditions on earth have changed over time, the number of possible minerals has expanded. Cellular life developed initially in anoxic and sulfidic seawater, and metabolism was based on iron-, manganese- and molybdenum-binding proteins. Those nutrients were provided at hydrothermal vents. As cyanobacteria generated oxygen and changed the chemistry of the oceans, zinc, copper and vanadium became more available. Modern forms of life are based more on zinc-, copper- and vanadium-binding proteins.

For example, after cyanobacteria generated large quantities of oxygen and transformed earth's atmosphere, new copper minerals developed on earth. They included copper sulphates, expanding the number of copper-based minerals beyond the sulfides that formed before the Great Oxygenation Event.1

Some metal ore deposits discovered in Virginia may have formed on island arcs 500 million or more years ago. Subduction of the edge of an arc led to continental crust melting at depth, then rising again to the surface as magma in volcanoes. As those island arcs were accreted to the edge of Laurentia in mountain-building "orogenies" 450-250 million years ago, new melting would have occurred. Old concentrations of minerals could have been remelted and redeposited, while new ore deposits were formed during the Taconic, Neo-Acadian, and Alleghenian orogenies.

Ore deposits worth mining are formed by concentration of minerals that were once more-evenly distributed within oceanic and crustal bedrock. Heat and pressure from igneous and metamorphic activity melted different minerals at different temperatures. Minerals differentiated in the molten rock, with some getting mobilized as molten fluids while other minerals were still frozen in a solid state. Minerals moved at different times and temperatures with hydrothermal fluids. The fluids flowed through fractures, before cooling and crystallizing to form ore bodies in lenses and veins:2

Gold is concentrated in and around the Chopawamsic Terrane north of the James River, and in the Carolina Slate Belt south of the river. Most rocks in the Virgilina District in the Carolina Slate Belt were created by consolidation of fragments blown out of volcanoes. The mineral deposits:3

European colonists were not the first geologists or miners in the Western Hemisphere. Archeologists have discovered evidence that red ocher, rich in hematite (an iron oxide), was excavated from caves in Yucatan up to 12,000 years ago. Sea level rise later caused the caves to flood, protecting the evidence - including charred wood that was used to date the age of the mining activity.4

Paleo-Indians mined flint and jasper, then heated and shaped it to manufacture sharp knives, projectile points, and other tools. Catoctin greenstone was valued in places where it was not available. Steatite (soapstone) was cut out of the ground and shaped into containers and bowls. Trading networks distributed valued rocks to the coastal areas and shells inland, for use as tools and as prestige goods.

Starting about 3,000 years ago, clay was the primary resource used by Native Americans in order to make pottery. The clay started as feldspar and other silicate minerals in the metamorphic rocks of the Piedmont. Slowly weathering by hydrolysis transformed the crystals in the bedrock into clay minerals that washed downstream into the Coastal Plain.

Native Americans dug clay from riverbanks and floodplains, using tools made from animal bones and wood. The raw material was processed by hand and feet to remove rocks, sand, organic material, and other impurities. A "temper" of crushed shell, sand, or other material was added to the clean clay before making pottery. The temper allowed steam to escape, rather than create a crack, when the clay was heated in a fire to create watertight pottery.

Native Americans also evaporated natural brines found at "licks" to produce salt. Before arrival of European colonists, salt was used as a condiment to flavor food rather than as a preservative. In 1567, a Spanish expedition may have marched to modern-day Saltville and initiated the first land-based exploration of Virginia.5

Native Americans were savvy geologists, recognizing high-quality clay deposits for pottery as well as rocks suitable for flaking into projectile points and other tools

Source: National Park Service, Pottery Making 4

The first Europeans to reach Virginia prioritized a search for metal. Gold, silver, copper, and lead were more valued in Europe than flint, clay, or salt.

The English colonists who landed on Roanoke Island in 1585 included Joachim Gans. He was the first practicing Jew known to land in North America, but the English overlooked his religion because he was an experienced metallurgist. He set up a workshop an assayed ore collected near the Outer Banks, in hopes of discovering precious metals comparable to those found by the Spanish in Central and South America.

Archeologists discovered about 400 years later that the crucibles used in his high-temperature furnace revealed traces of iron, silver, and copper. However, no ores worth mining were discovered. The soft sediments of the Coastal Plain had some iron deposits, but no gold, silver, copper, or other minerals beyond an unending supply of useless quartz. The copper objects worn by the Algonquian-speaking Native Americans around Albemarle-Pamlico Sound had been acquired by trade with tribes living west of the Fall Line; there was no local production.6

King James I reserved a portion of gold, silver, and copper that might be discovered in Virginia. In the First Charter issued in 1606, he included language reserving to the Crown 20% of the value of gold and silver and 6.7% of the value of copper:7

The reservation of "the fifteenth part" of copper was dropped in the Second Charter issued in 1609. The Virginia Company was explicitly granted all rights to whatever copper, lead, tin, and other minerals might be discovered in the colony.8

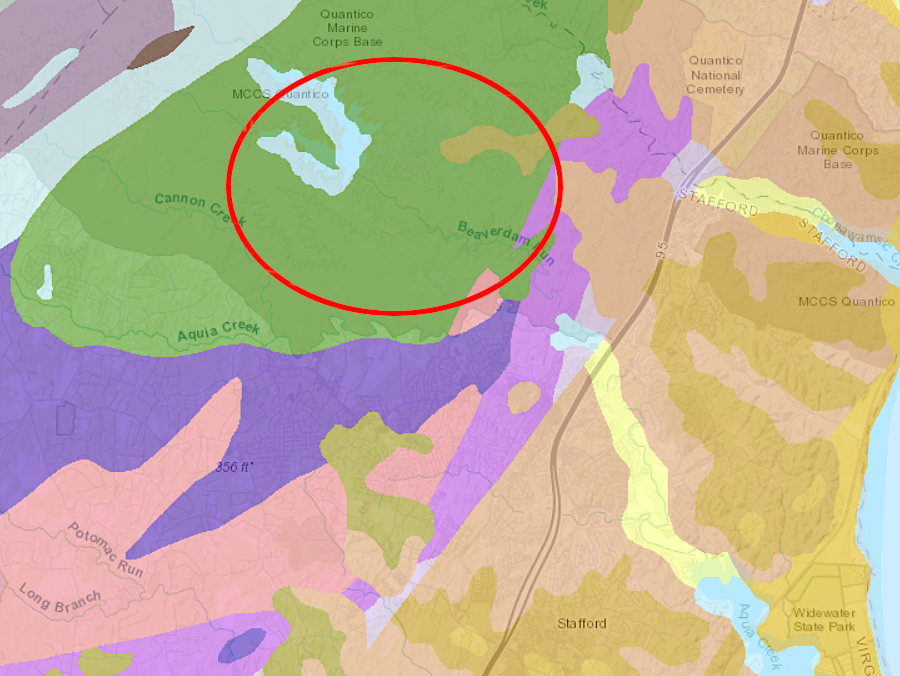

The colonists at Jamestown had no more success than at Roanoke Island. John Smith did discover the Patawomecks mining silvery flakes, similar to antimony, six-seven miles inland from the headwaters of Aquia Creek. That material was useful for decorating one's skin, but had no monetary value for the colonists. As Smith described it:9

the antimony mine would have been located in the metamorphic rocks of the Chopawamsic Terrane, west of the Fall Line near the modern Lunga Reservoir

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Interactive Geologic Map

In the Second Supply which left London in October, 1608, the Virginia Company sent eight Germans and Poles as research scientists to Jamestown. Alchemy blurred science and the supernatural in 1608, but the Virginia Company invested in solid research based on actual experimentation.

The glassmakers experimented with manufacturing "trials" of glass in small crucibles. Silicon dioxide (SiO2) from sand was mixed with soda ash (Na2CO3), which may have been produced by burning marsh grasses that washed up on the shoreline and were easy to collect. The experiments also included adding lime from oyster shells. The formula for making soda-lime-silica glass had been known since the days of Rome. Soda ash lowered the temperature at which the sand melted, and lime was a stabilizer which create a stronger glass that resisted decay from water and humidity.

The Germans and Poles may also have produced a potash-lime-silica "forest glass" using potassium rather than sodium. That experiment would have involved generating potash by burning beech trees. Ash from the furnaces where wood was burned to melt the sand could have provided the potash.

The materials used in Virginia were readily available in England as well, and cullet (broken glass) might have been carried from England to jumpstart the "trials." The glassmaking experiment was to determine if the abundant wood in Virginia could be used to melt the even more abundant sand in Virginia and manufacture glass. The concept of Virginia as an industrial colony faded quickly after the Starving Time in 1609-1610 and the development of tobacco as a staple export crop in the following decade. Labor in Virginia was valued more for agriculture than for cutting firewood to make glass. (Today, the reconstructed glass house at Jamestown uses natural gas to fire its manufacturing display.)10

In addition to metallic ores, the Virginia Company sought medicinal clays. At the time, clays were prescribed to alleviate diarrhea and intestinal afflictions. The company sent Dr. Lawrence Bohun to Virginia in 1610, and he identified a white clay "Terra Alba Viginensis") thought to absorb poisons and alleviate fevers.11

The primary minerals produced by Virginia colonists in the 1600's mimicked the pattern of the Native Americans. Clay was used to produce brick for houses, and salt was extracted from seawater for preserving fish and pork. The English had no interest in finding high-quality flint or jasper to create projectile points and other tools; guns were preferred over bows and arrows. Both colonists and Native Americans preferred metal tools rather than stone tools.

The first major mineral development project was an iron furnace built in 1619 at Falling Creek, near Henricus. That project ended with the 1622 uprising of the Native Americans. Governor Spotswood initiated new iron mining operations in the 1720's, and the Neabsco Iron Works in what is now Prince William County in the 1730's started smelting ore in 1737.12

In the 1700's, clay, iron, lead, and salt were the primary minerals developed by the English colonists. Coal was also mined near Richmond. Robert "King" Carter launched a copper mining project in Northern Virginia in 1729, but the ore was exhausted by 1731.

Col. John Chiswell started mining the zinc-lead deposit on Cripple Creek in what later became Wythe County in 1756. Moses and Stephen Austin gained control in 1780, and the valuable deposit at Austinville was mined for lead, zinc, and hematite until 1981.13

Right after the American Revolution, the brines at Saltville were developed for industrial-scale production of salt. A century later, the Mathieson Alkali Works used the brine to produce soda ash and chlorine.

In the 1800's, iron furnaces fueled by charcoal supplied pig iron to foundries. Gold mines were opened in the Gold-Pyrite Belt west of the Fall Line. The Sulphur Mine in Louisa County produced iron initially, but was re-opened after the Civil War to extract sulfur. The Cabin Branch Mine in Prince William County was developed primarily for its sulfur rather than for associated metals.14

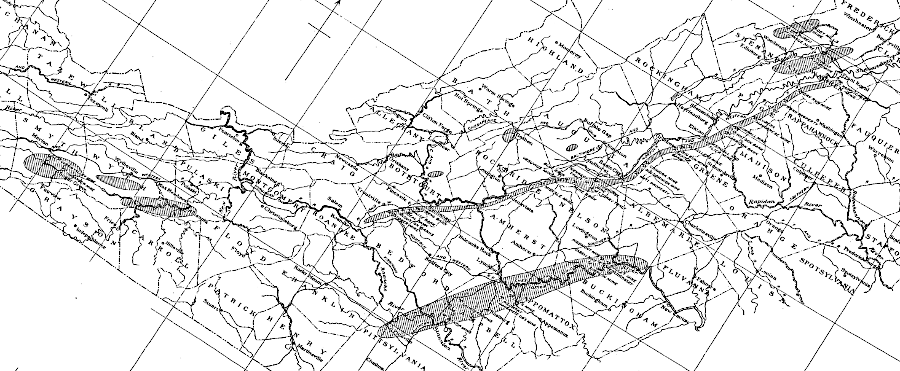

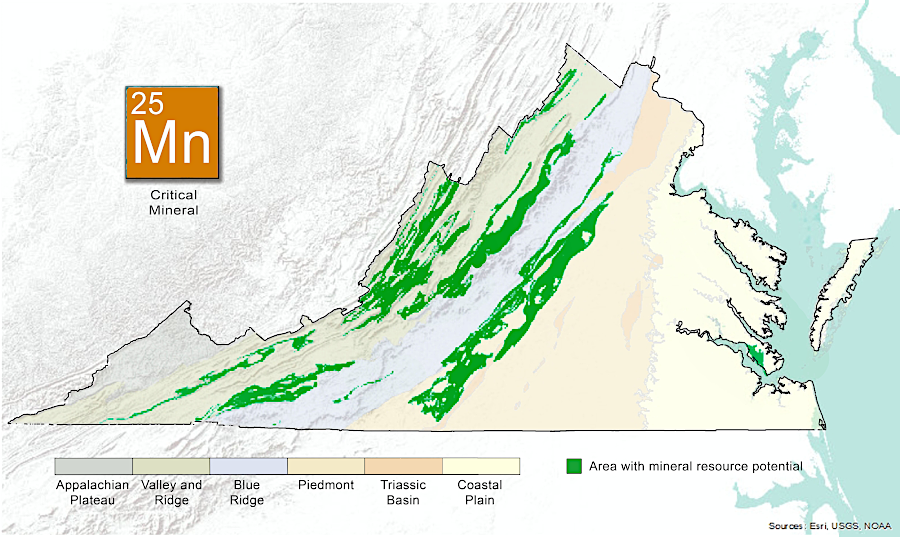

The source of manganese in Virginia is mafic and other igneous rocks, particularly in the Blue Ridge and the western Piedmont. Erosion and re-deposition has created potentially valuable deposits at sites in both the Valley and Ridge and the Piedmont physiographic provinces. A 1910 report by the US Geological Survey also noted that several hundred tons of manganese-rich ore had been mined from a site on the Coastal Plain near City Point in Prince George County.

the principal manganese mines and the probable extent of the ore-bearing areas in Virginia, as known in 1910

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Manganese Deposits of the United States (p.37)

Virginia's first manganese mine opened in 1834 at Paddy’s Run in Frederick County. After the Civil War multiple pockets or ore were mined from clay formations located east of the Blue Ridge in Nelson County, plus in the James River and Roanoke (Staunton) River valleys. In 1910, the Piedmont Manganese Company mine in Campbell County, two miles southeast of Mount Athos, had underground drifts at the 80-foot and 105-foot levels. At the time, the manganese was used for coloring fancy brick.

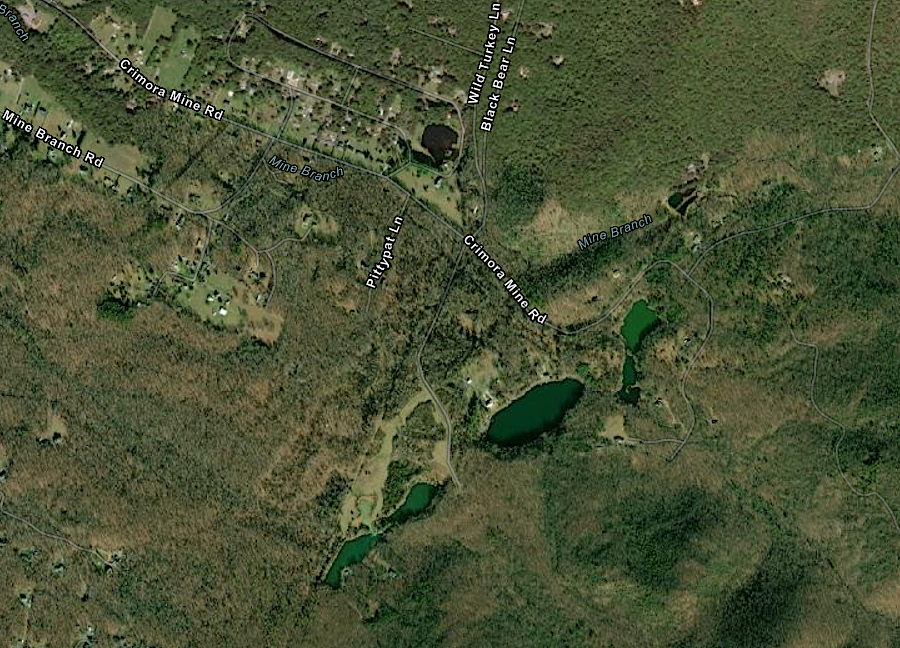

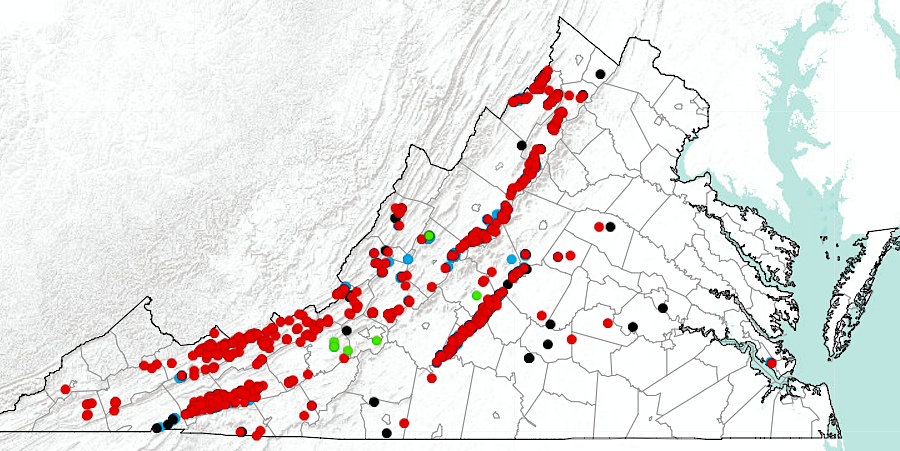

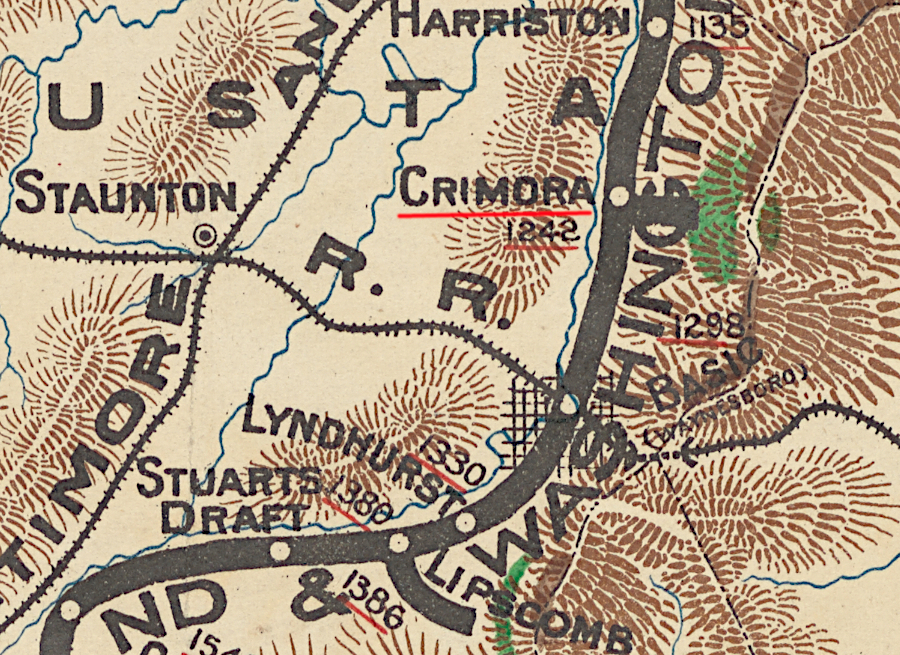

In the early 1900's, there were 15 small manganese mines on the western flank of the Blue Ridge. They stretched from Front Royal to Roanoke. One, the Crimora Mine in Augusta County's Dorsey Hanger Hollow, was the last operating manganese mine in Virginia.

The 1910 report described the geologic setting of the manganese deposits:15

The Crimora Mine opened in 1866. The demand for manganese, used to remove oxygen and sulfur from molten iron in order to create steel, spiked in World War I. At that time, the mine became the largest producer of manganese in the world. After the war, demand plummeted and the Crimora Mine closed.

It reopened in 1937 as World War II loomed, then closed again after 1945. The US Congress created a new demand during the Cold War, passing legislation in 1954 to create a stockpile of critical and strategic minerals. Federal subsidies led to the Crimora Mine operating again until the subsidies were eliminated in 1958. The site on the mine evolved into a modern vacation resort, the Crimora Mine Retreat, with three lakes in pits created during the mining period.

lakes now mark the location of the Crimora Mine in Augusta County, once the largest producer of manganese in the United States

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

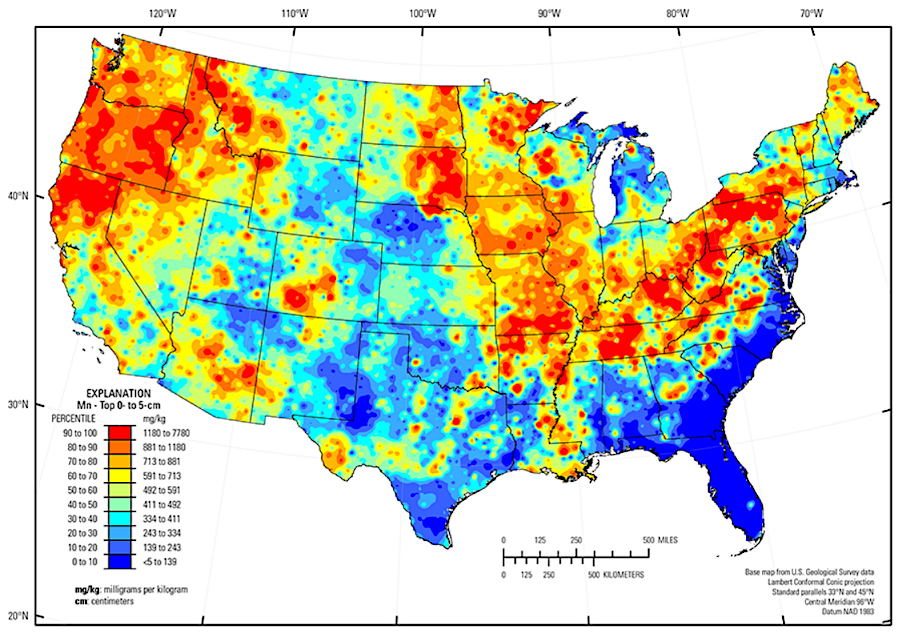

Today, 13% of especially strong steel is manganese, as is 1.5% of aluminum drink cans to reduce corrosion. Manganese is one of the critical minerals required for production of batteries for electric vehicles (EV's), along with lithium, nickel, cobalt, and graphite.

To qualify for the Federal subsidies for EV's included in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, batteries in such cars must use a high percentage of US-based materials. That requirement could spur renewed interest in identifying commercially-viable deposits of manganese in Virginia.16

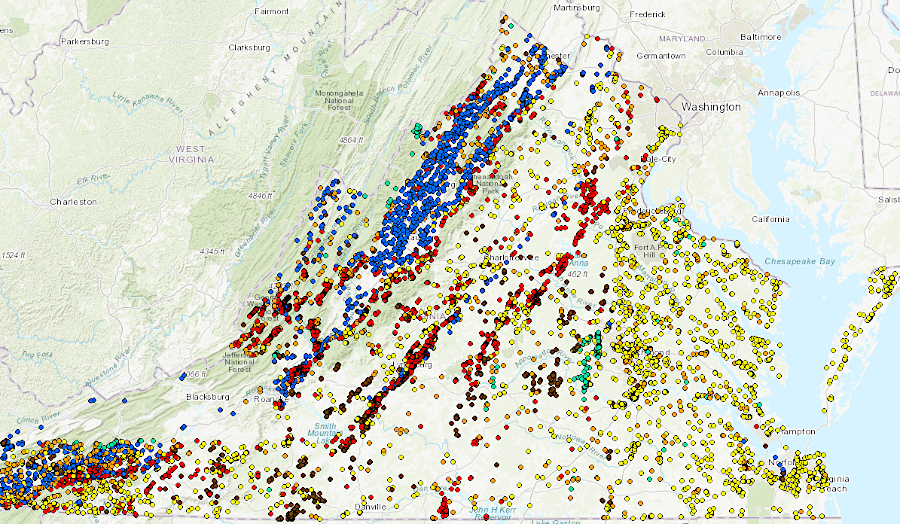

the percentage of manganese oxides in soil is a clue to finding potential commercial deposits for production of batteries for electric vehicles

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Geochemical and Mineralogical Maps, with Interpretation, for Soils of the Conterminous United States

manganese prospects are concentrated in the western Piedmont and the Valley and Ridge physiographic provinces

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Manganese Occurrences in Virginia

commercial deposits of manganese are likely to be located near the Blue Ridge

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Manganese

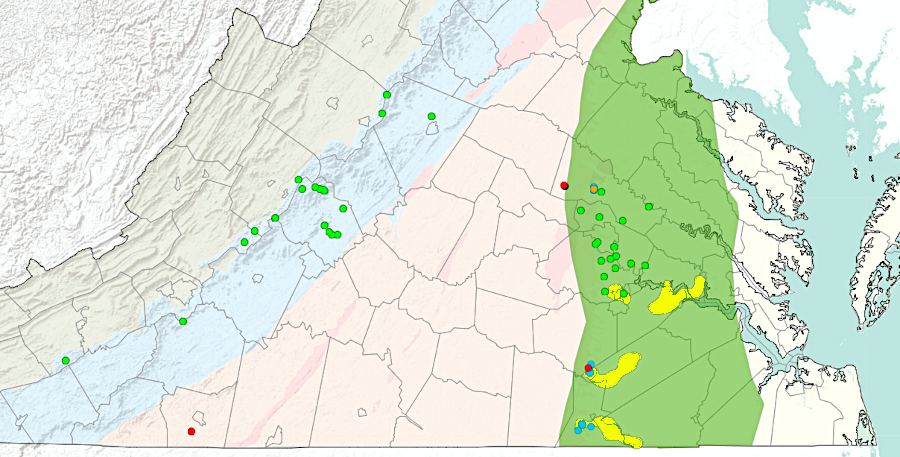

Titanium mining began in the 1940's around the Blue Ridge. Discovery of the Old Hickory Deposit, where titanium was concentrated in sediments on the Coastal Plain, led to mining in in Sussex County between 1997-2016.17

titanium particles eroded from the Blue Ridge and accumulated as heavy sands on the Coastal Plain, when sea level was higher

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Heavy Mineral Sands

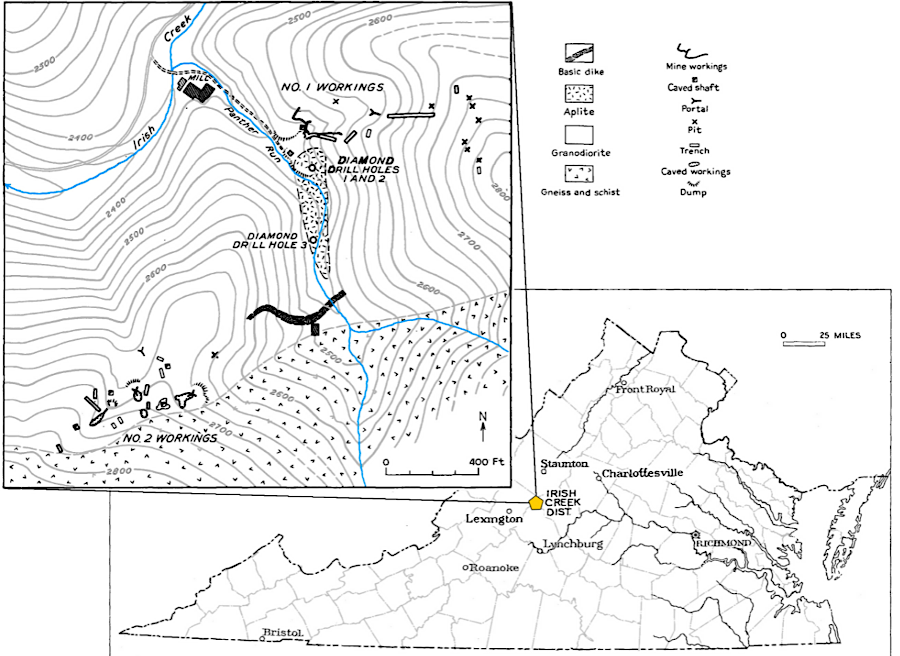

One deposit of the mineral cassiterite with enough tin to be commercially valuable has been found in Virginia. The site on Panther Run, a tributary to Irish Creek in Rockbridge County, was identified before 1846. Mining occurred intermittently between 1884-1919:18

Virginia's commercial tin mine was in Rockbridge County

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Tin

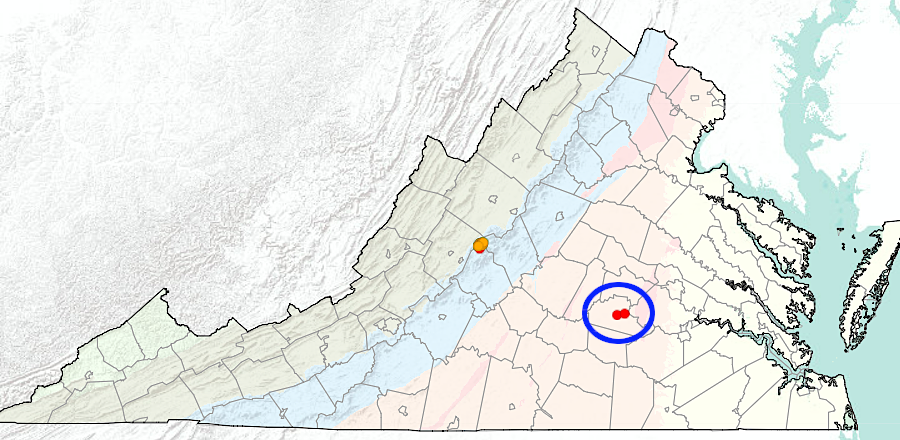

tin was produced as a secondary product at the Morefield Mine and Rutherford #3 (blue circle)

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Tin Occurrences in Virginia

Zirconium is a non-reactive metal, and used in Virginia as a coating on fuel rods in nuclear power plants. Zirconium is found in nature associated with hafnium and titanium. Deep mantle-sourced magma is relatively rich in those elements. They reached the surface often within crystals of zircon (ZrSiO4).

Zircon crystals are extremely slow to dissolve in water; they are highly resistant to weathering. While other minerals (even quartz crystals) end up in solution, zircon crystals get transported downstream. They accumulate in placer deposits within Coastal Plain sediments, and the heavy zircon crystals can be separated and mined commercially together with heavy titanium crystals.

Zircon is the oldest mineral found in Virginia, and one crystal from Australia is around 4.3 billion years old.

Zircon crystals are used for dating the age of rocks. Zircon crystals trap uranium atoms naturally within their lattice when it forms as magma cools, but the structure excludes lead atoms at the time of crystallization. After radioactive decay of uranium creates new lead atoms, the ratio of lead/uranium can be used to date the age of the zircon crystal.

Those dates are valuable in determining the source rocks of sedimentary formations. Zircon dates can be used to determine if terranes that accreted to Virginia during the Taconic, Neo-Acadian, and Alleghenian orogenies were associated with Africa or North America.19

zirconium and hafnium end up concentrated (yellow blobs) in Coastal Plain sediments, just like titanium

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Hafnium and Zirconium Occurrences in Virginia

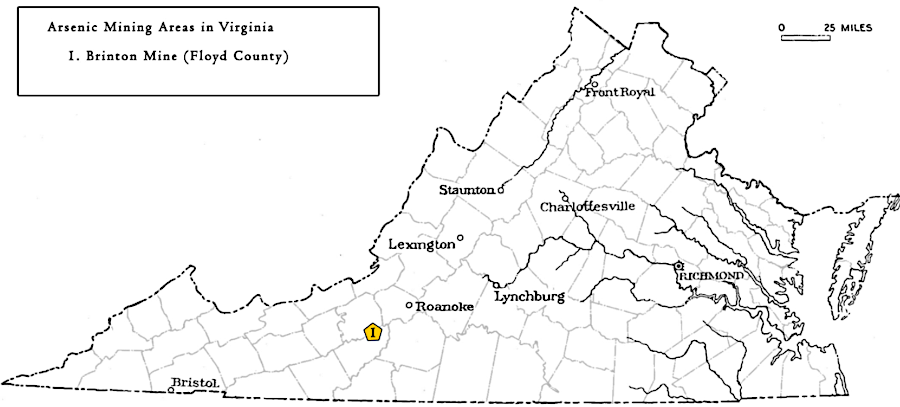

Arsenic was mined in Floyd County between 1902-1917, where an ore body 3-14 feet thick went 120 feet deep. The processing plant at the Brinton Mine was dismantled in 1919. The Virginia arsenic was used to produce insecticides. Native Americans has discovered patches of arsenic ore far earlier, and used it as a pigment to paint yellow streaks on their bodies.

John Lederer reported seeing in 1670 four Native Americans on the Roanoke River decorated with Auripigmentum (probably As2S3). He would have stayed at the town of Akenatzy longer to search for the source of the mineral. However, after his hosts murdered the Rickohockan ambassador and his five traveling companions one evening, Lederer chose to "slunk away."20

Virginia has produced arsenic at one location, the Brinton Mine in Floyd County

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Arsenic

The Tungsten Queen deposit in Mecklenburg County, Virginia and Vance County, North Carolina includes over 50 tungsten-bearing veins in a 13-km long, 2-km wide belt. Mines with shafts extending as deep at 1,500 feet extracted wolframite, the primary mineral with the element tungsten, between World War II and 1971. After the price dropped, mining stopped. Today, the Kerr Reservoir covers much of the tungsten ore.

According to the US Geological Survey21

Exploration geologists must decipher clues from multiple sources to identify ore deposits worth mining; minerals are not evenly distributed across Virginia. Almost all limestone quarries are west of the Blue Ridge. On the Coastal Plain, nearly all mining is associated with production of sand, gravel, and clay. Coal deposits are located in three physiographic provinces - the Piedmont (Triassic Basin near Richmond), the Valley and Ridge (including Merrimac Mine in Montgomery County), and the extensive coal fields on the Appalachian Plateau.

Source: Friends of Mineralogy Virginia Chapter, Minerals of Virginia

On the Atlantic Ocean seafloor, far east of Virginia's three mile boundary, are nodules rich in copper, nickel, manganese and other minerals. Hydrothermal fluids at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge are creating new ore deposits regularly.

most limestone quarries (blue) are west of the Blue Ridge, while on the Coastal Plain most mining is for sand/gravel (yellow) and clay (orange)

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy

Mining of over 50 different minerals in Virginia has produced useful materials for manufacturing, but environmental impacts have been significant in places. Until the 1970's mines were abandoned without consideration of the environmental impacts. Sulfur-rich minerals exposed to air and water with dissolved oxygen generate acidic runoff. Some streams, such as Contrary Creek in Louisa County, have been heavily damaged by a pH too low to support aquatic life.

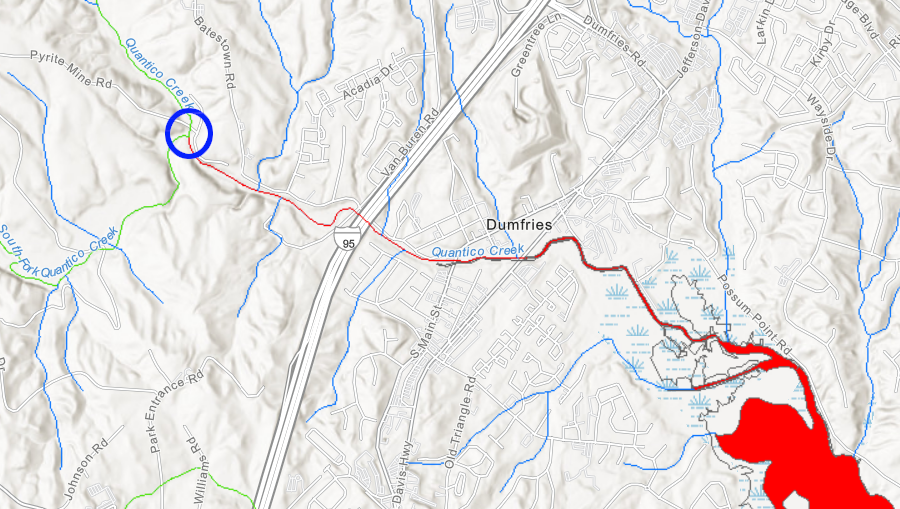

Reclamation projects have mitigated the impacts in some places. The National Park Service reclaimed Cabin Branch Mine in 1995, placing lime and soil over tailings to isolate the sulfur-rich waste material left as heaps in the creek valley when the mine closed in 1921. Vegetation has covered the old mining site. However, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality's 305(b)/303(d) Water Quality Assessment Integrated Report (the "Dirty Water List") for 2020 still lists Quantico Creek as impaired due in part to excessive levels of copper. The stream segment downstream from the old mine site was Not Supporting for Aquatic Life, Wildlife, or Recreation.22

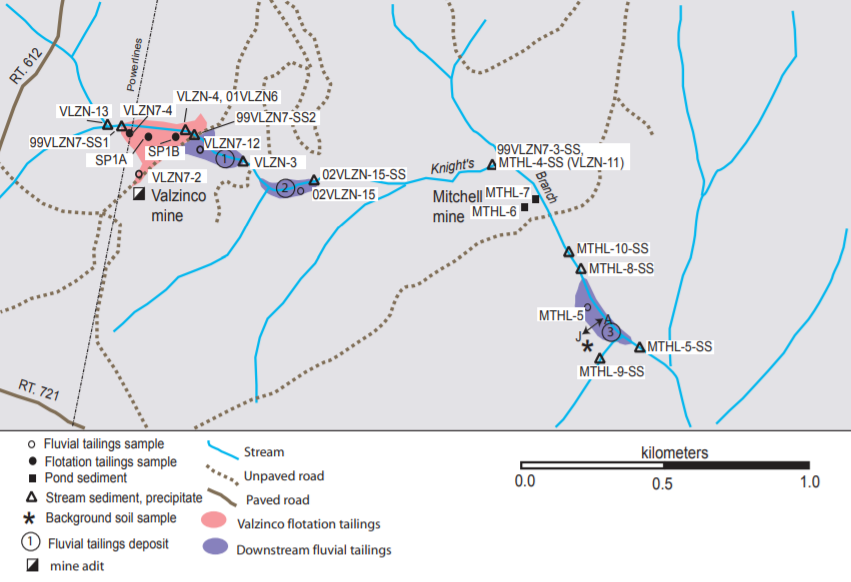

tailings that had washed down Knights Branch from Valzinco and Mitchell mines in Spotsylvania County contained lead beyond levels deemed to be safe

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Geochemical and Mineralogical Characterization of the

Abandoned Valzinco (Lead-Zinc) and Mitchell (Gold) Mine Sites Prior to Reclamation, Spotsylvania County, Virginia (Figure 3)

heavy metals leached from mine tailings at the old Cabin Branch Mine (blue circle) still pollute Quantico Creek a century after mining stopped

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Environmental Data Mapper

The US Congress passed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act in 1977, requiring reclamation of coal mines. In Virginia, the Orphaned Land Program was established in 1978 to reclaim non-coal mines. Mine operators are required to contribute to the Mineral Reclamation Fund, and the first of the 4,000 orphan mines in Virginia was cleaned up in 1981.

The Orphaned Well Fund was created in 1990, to plug orphaned wells abandoned prior to July 1, 1950.23

sand and gravel mining is most common in the loose sedimentary formations of the Coastal Plain

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, "Mineral And Fossil Fuel Production In Virginia (1999-2003)," Sand and gravel extraction sites in Virginia with active permits during 1999-2003 (Figure 6)

all crushed stone operations are west of the Fall Line - on the Coastal Plain, gravel pits simply extract stone already crushed through natural erosion and transport

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, "Mineral And Fossil Fuel Production In Virginia (1999-2003)," Map of crushed stone operations in Virginia with active permits during 1999-2003 (Figure 10)

in 1890, the Norfolk and Western Railroad had a branch line at Crimora to manganese mines

Source: New York Public Library, Mineral territory tributary to Norfolk and Western Railroad (1890)

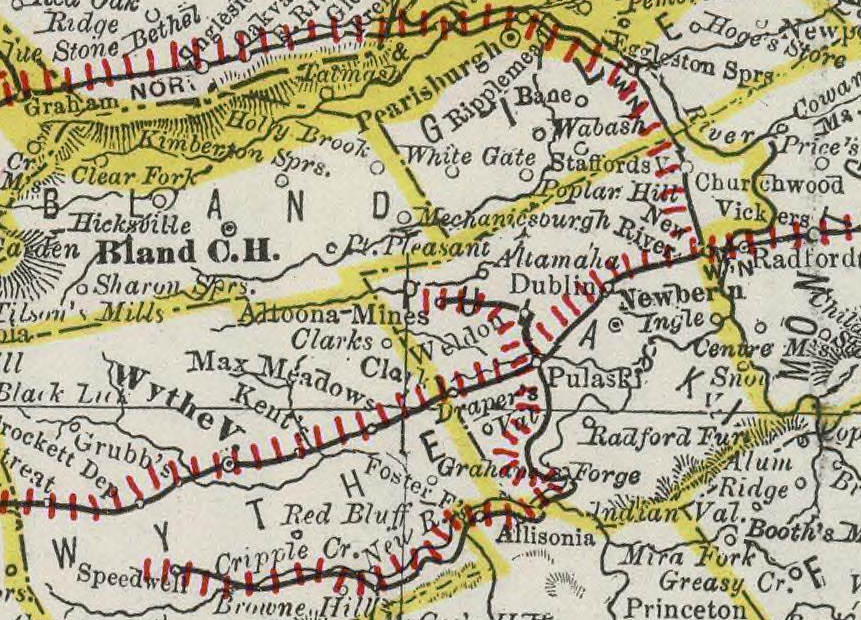

revenues from transporting mineral resources justified railroad development in southwestern Virginia

Source: David Rumsey Map Collection, Rand McNally," Virginia (1889)

efflorescent sulfate salts grew on tailings from Valzinco and Mitchell mines in Spotsylvania County

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Geochemical and Mineralogical Characterization of the Abandoned Valzinco (Lead-Zinc) and Mitchell (Gold) Mine Sites Prior to Reclamation, Spotsylvania County, Virginia (Figure 4)

minerals with more protons than iron were formed by the collision of two neutron stars or when the nickel-iron core collapsed in a Type II supernova

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Messier 16 (The Eagle Nebula)