For 15,000 or so years, wood was the primary fuel for cooking food and heating dwellings in Virginia.

For 15,000 or so years, wood was the primary fuel for cooking food and heating dwellings in Virginia.

For 15,000 or so years, wood was the primary fuel for cooking food and heating dwellings in Virginia.

For 15,000 or so years, wood was the primary fuel for cooking food and heating dwellings in Virginia.

Fires were kept burning constantly for cooking or warmth, inside shelters made of bark and reeds with roofs made from similar plant material. The small fires were kept smoldering even in the summer. The heat kept everything dry, blocking mold from damaging the bark/reed shelters.

Modern re-creations of Native American dwellings decay in about two years. Many sites with representations of pre-colonial Native American housing units use cheap, easy-to-replace woven mats imported from China for the walls and roofs. No one lives in those living history sites year-round; no fires keep the structures constantly dry.

The re-creation of Wolf Creek Indian Village in Bland County used a different approach. The site started with fiberglass coverings on a wooden frame, but in 2012 replaced the exteriors with bamboo. The fiberglass was easy to maintain, but the recreated dwellings suffered from the greenhouse effect. Sunlight penetrated the material, but re-radiated energy at longer wavelengths was trapped by the fiberglass. Walking into the fiberglass version during the tourist season - summer - was like walking into an oven.

fiberglass and bamboo versions at recreated Wolf Creek Indian Village, of what were originally bark-covered structures

Small fires maintained constantly inside Native American shelters also protected the furs and skins stored in the dwellings. In addition, the smoke would reduce the number of mosquitoes and other bugs in the thatch-covered or bark-covered huts. When Pocahontas saw the smoke-filled skies of London, she might have considered the acrid smell of burning coal to be unpleasant - but she would have been familiar with a constant smoky haze in areas occupied by people.

Where did the wood come from? The Native Americans would have collected all the "dead and down" wood first. After all, it required great effort to cut down even small trees for firewood, using just sharp rocks and shells. Woods near Native American towns must have looked like the woods we see today near modern campgrounds at the end of the vacation season.

(Think large bonfires were common before the Europeans arrived with metal axes and today's chainsaws, or do you think that the Native Americans relied upon small fires and conserved their energy - except for very special occasions?)

inside a Totero dwelling (as reconstructed at Explore Park), deer skins were used for bedding/cushions and there were no chimneys

Firewood was the primary source of energy for European colonists as well as Native Americans. Wood heated their first homes in Jamestown, and a century later the mansion houses on tobacco plantations included massive fireplaces for winter heat. The slaves in the kitchens used smaller fireplaces for cooking, or to heat water used for the laundry.

Firewood was not just a domestic energy source. Wood was the industrial fuel that provided the energy for smelting iron in Virginia, until after the Civil War. The heat energy in the wood was concentrated by converting it to charcoal, before it was added to the furnace along with iron ore and limestone.

Charcoal has twice the energy value as regular wood, so it created a fire hot enough to melt the iron out of the ore (rock). The trick to making charcoal is to heat wood to 518°F in the absence of oxygen. 1

Making charcoal was a dirty job. A collier (charcoal maker) would clear a flat surface in the woods, up to 40 feet wide, down to bare dirt. Up to 30 cords of wood cut in 4' lengths would be stacked up in a carefully-designed heap around a central pole, creating a chimney in the middle. The stacked wood would be covered with mud, dust and leaves to exclude air, and a fire would be lit in the center.

Some of the wood in the stack would burn. The charcoaling process drove off the water in the wood and concentrated the energy. Heating the stack converted wood into charcoal... so long as the mud coating excluded most oxygen. A collier who screwed up (perhaps by falling asleep) and let uncontrolled air get into the pile would end up with a raging bonfire - and no charcoal. (Today, charcoal is heated in air-tight iron structures,

wood was stacked with a "chimney" in center, then covered with earth before being set on fire and converted to charcoal

Source: National Park Service: Catoctin Mountain Park, Charcoal/Iron Industry

The process of converting a stack of wood into charcoal took a week or two of 24-hour attention. Colliers would poke holes/seal holes in the covering layer to get the right pace and pattern of heating. At the end of the "wood cooking," colliers peeled back a portion of the covering and raked out some charcoal. They had to work quickly, until the opening generated a draft and the charring wood started to ignite. Then it was time to re-cover the stack, and perhaps move to the other side to rake out a little more over there.

As described by the US Forest Service:2

charcoal mounds were carefully covered with dirt and leaves to seal off oxygen that might allow the wood to burn completely to ash, and charcoal could be extracted in stages before covering the pile again

Sources: National Park Service, American Charcoal Making, US Forest Service, Wane National Forest History & Culture

Iron manufacture on a very small scale in Virginia started at Jamestown. A substantial investment was made to create an iron production operation at Falling Creek, near the Henricus settlement. Unlike England, the new colony had plenty of trees to provide energy - but the Falling Creek project ended after the Powhatan uprising of 1622 killed the ironworkers and destroyed the site.

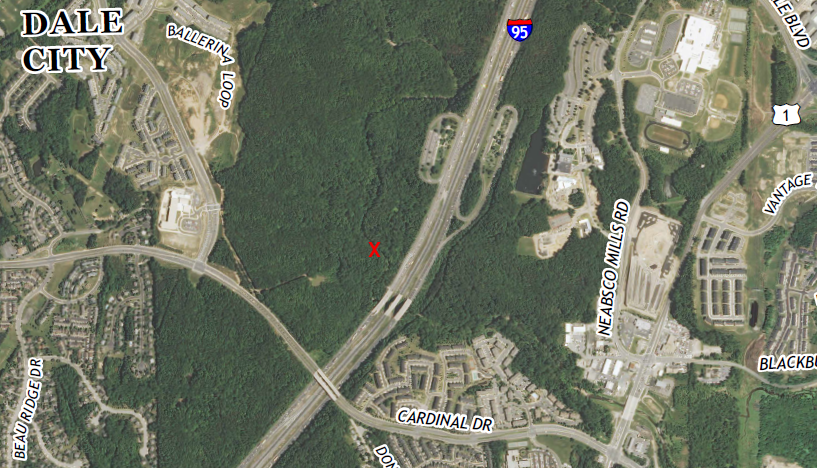

Later, Governor Spotswood was a champion of creating an iron industry in Virginia, but officials in London opposed the competition. Various British laws tried to block iron manufacture in the colonies, to protect the domestic producers in England. Nonetheless, the first industrial site in Northern Virginia was an iron furnace established on Neabsco Creek in Prince William County, near the present-day Potomac Mills shopping district.

Neabsco Iron Works were located south of Potomac Mills, on Neabsco Creek near a modern rest area on I-95

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Quantico 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (Revision 1)

The hillsides along Neabsco Creek were denuded, as trees were converted into charcoal to fuel the Neabsco Iron Works furnace. Erosion from the hillsides would have been substantial, filling up the bed of the creek with sediment that you can still see today (look next to the Sheetz gas station, downstream from the Neabsco Creek bridge over Route 1).

Iron manufacturing required massive amounts of fuel, and wood fueled Virginia's iron furnaces until after the Civil War. About an acre of forest was cleared to produce the 750 bushels of charcoal needed for one day of typical furnace operations. As described in one report:3

workers carried baskets of charcoal across a ramp to dump into the top of a burning iron furnance

Source: National Park Service, Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site

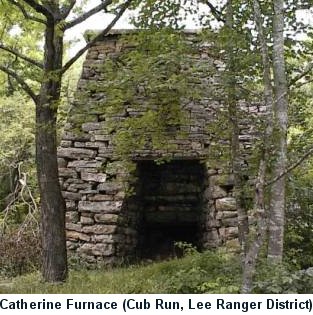

After settlement moved inland, the virgin forests of the area near the headwaters of the Ni River were cut in order to supply the charcoal for the Catharine Furnace. Several furnaces were named "Catharine" or "Catherine," in different areas of Virginia. A Shenandoah Valley furnace, with a similar name except for one vowel - Catherine instead of Catharine - is shown on the right.

After settlement moved inland, the virgin forests of the area near the headwaters of the Ni River were cut in order to supply the charcoal for the Catharine Furnace. Several furnaces were named "Catharine" or "Catherine," in different areas of Virginia. A Shenandoah Valley furnace, with a similar name except for one vowel - Catherine instead of Catharine - is shown on the right.

The trees around the Catharine Furnace on the Ni River were cut prior to the Civil War. The trees re-grew naturally, and by in 1864 the land near the furnace was a dense tangle of small trees at an early stage of growing back into a mature forest, . The area was known locally as the Wilderness. It became famous in May, 1864 when the Union Army started the Overland Campaign with the "Battle of the Wilderness," on the way to capturing Richmond a year later. A Union General, Winfield S. Hancock, described the area around Catharine Furnace in his official report of the battle:4

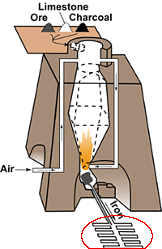

In the 1700's and 1800's, iron furnaces were piles of stones that were fueled from the top, and iron was removed from the bottom. The furnace would be gradually heated by first filling it with charcoal, then lighting it at the top of the chimney. As the charcoal burned down to the bottom, the stone would expand gradually. It was common to line the inside of iron furnaces in the 1800's with a form of "firebrick" that was able to withstand the high temperatures inside the furnace without cracking.

If an ironmaster was unskilled in starting a "blow" and the interior of the stone furnace heated up too rapidly, the moisture in the stone would flash into steam and crack the lining of the furnace. The inside of the stone walls of Chapman's Mill at Thoroughfare Gap acted like an iron furnace when an arsonist set fire to that structure in 1998, and the stones cracked and spalled.

After the charcoal inside the furnace burned down, wheelbarrow loads of charcoal, iron ore, and limestone would then be dumped in from the top. It was a nasty job, since hot smoke was rising out of the furnace the entire time. The burning charcoal, mixed with the other materials, would heat the mix inside the furnace. When the temperature was hot enough, iron would melt out of the ore while silica turned into slag.

The charcoal fire inside an iron furnace would reach 900°C, the temperature required to separate the oxygen and iron atoms and "reduce" the iron oxide in the ore to a pure form of iron. Ironmasters were chemists as well as cooks, and altered the ingredients in the furnace based on the quality of the local ores and charcoal. Ironmasters almost always added limestone or oyster shells. That provided calcium, a chemical flux that helped separate the iron from the other minerals in the ore. Calcium bonded with silica in the slag - the glassy waste product from iron manufacturing. Otherwise, iron atoms bonded with the silica, and were not "reduced."

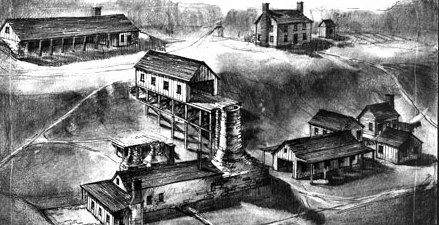

possible layout of facilities at Catharine Furnace (Wilderness Battlefield)

Source: National Park Service, Virtual Tour Stop, Catharine Furnace

The ironmaster would note the character of the smoke. At a certain point, perhaps once a day, he would decide it was time to tap into the pool of molten iron that accumulated at the bottom of the furnace. A hole would be poked into a clay wall at the bottom of the furnace, allowing the molten iron to flow out into channels scratched out in flattened sand arranged in front of the furnace. The cooling rows of iron bars resembled piglets nursing from a sow, so the product was called "pig iron."

After the valuable iron was tapped, the molten silica would be drained. That product, derived from the sandstone matrix component of the iron ore, was essentially glass. The silica-rich impurities occasionally would be used as road-building material, but normally were just discarded as waste.

iron tapped from the furnace resembled piglets suckling from a sow

Source: Maine Division of Parks and Public Lands, The Furnace at Katahdin Iron Works, Flickr