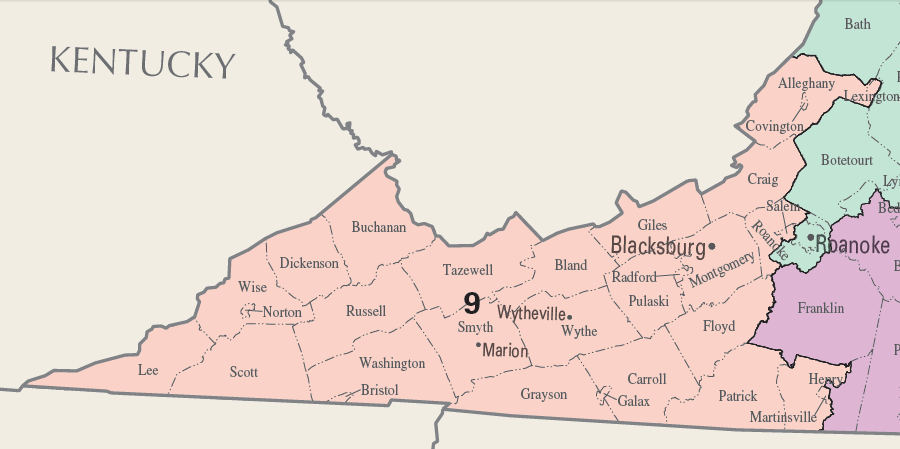

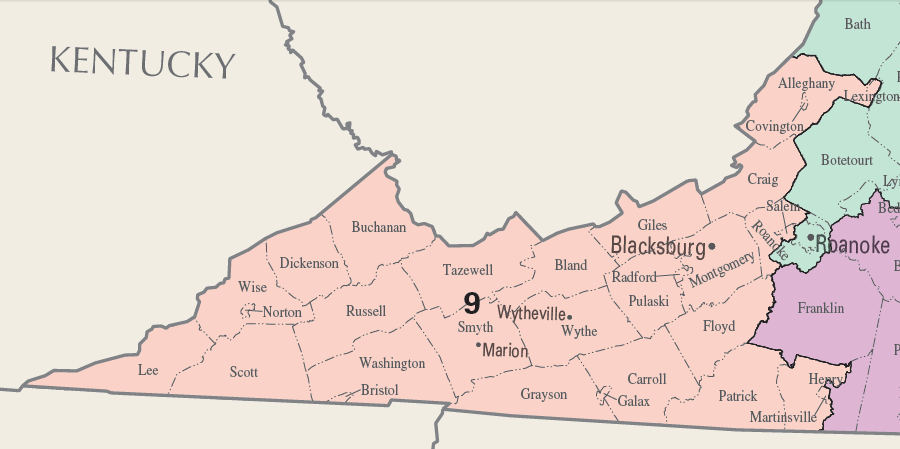

Virginia's Ninth Congressional District is located in Southwest Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas

Virginia's Ninth Congressional District is located in Southwest Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Atlas

Southwestern Virginia has been represented in the US Congress since 1789. The district boundaries have been revised every 10 years after completion of the census, and at some other times as well.

Initially, the region was part of the Third District. After Kentucky became a separate state in 1792, the region was part of the Fourth District. The designation of southwestern Virginia as the Ninth District has been consistent since Virginia was re-admitted to the Union in 1870, with the exception of 1933-35. Virginia eliminated district boundaries in the 1932 election and elected all nine members to the US House of Representatives "at large" for the 73rd Congress.1

in 1789, what is now southwestern Virginia was in the Third Congressional District

Source: Mapping Early American Elections, 1st Congress: Virginia 1789

in 1793, Kentucky was an independent state and what is now southwestern Virginia was in the Fourth Congressional District

Source: Mapping Early American Elections, 3rd Congress: Virginia 1793

The Ninth District elected Democrats to the US House of Representatives between 1872-1880. In 1879, the Readjusters built a coalition in the General Assembly to support funding of schools by readjusting the payment schedule for pre-Civil War debt, knowing that some of the state funding would finance schools for blacks as well as whites. Southwestern Virginia elected Rep. Abram Fulkerson, a Readjuster, in 1880.

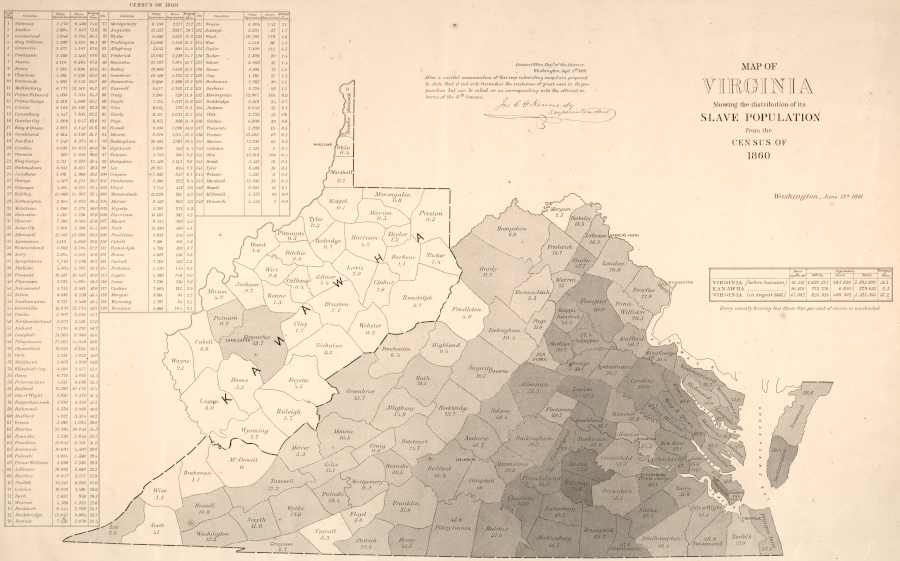

The Blue Ridge was a barrier that isolated Southwest Virginia from eastern Virginia until completion of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad to Bristol in 1856, and large-scale agriculture based on slavery was less common. The residents in the southwest were less interested in establishing segregation as public policy if the whites would also be punished by prioritizing debt repayment over schools. The voters already felt the General Assembly failed to provide southwest Virginia with its fair share of taxpayer-financed transportation infrastructure and other public services, though it did not secede and join West Virginia in 1863.

The small number of black residents in southwestern Virginia meant that nearly all state-funded school benefits would flow to the white community, so partnering with the Readjusters was politically feasible for Rep. Abram Fulkerson.

in part because southwestern Virginia had fewer slaves, it did not vote reliably Democratic as part of the Solid South after Reconstruction

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Virginia: showing the distribution of its slave population from the census of 1860

The Readjuster movement faded after 1883, but in the southwestern corner of the state the voters did not become reliable straight-ticket Democratic voters. They were more willing to support Republicans, especially for Federal office, and elections were hotly contested. Voter fraud was not uncommon, and the Ninth Congressional District became known as the "Fighting Ninth."

When Rep. Abram Fulkerson chose not to run after one term, in 1882 the district elected another Readjuster, Henry Bowen. Rep. Bowen was defeated by a Democrat in 1884, but won re-election in 1886 as a Republican. Rep. Bowen was defeated again by a Democrat in the 1888 election, flipping the district again.

The Republican, John Alexander Buchanan, retired after serving four years. He was replaced by a Democrat, James William Marshall.

The Ninth District elected a Republican again in 1892. James Alexander Walker had been elected Lieutenant Governor of Virginia in 1877 as a Democrat, but in 1893 he switched to the Republican Party before being elected in 1894 and 1896 to represent the Ninth District in the US House of Representatives.

His replacement also served two terms. William Francis Rhea was elected as a Democrat in 1898 and 1900, but Campell Slemp won the 1902 election. 2

In 1902, Campbell Slemp was elected as the congressional district's US representative. Slemp was a Republican, so the Ninth District clearly was not part of the "solid South" electing Democratic officials who promised to maintain segregation. In 1902, while a state convention was modifying Virginia's constitution to exclude blacks from voting and ensure the long-term dominance of the Democratic Party, the Ninth District was electing Republicans.

After Rep. Slemp died in office, his son C. Bascomb Slemp was elected in 1907 as his replacement. He was re-elected to serve seven full terms. Rep. C. Bascomb Slemp chose not to run in 1922, and served instead as secretary to President Calvin Coolidge from 1923-1925. "Secretary" at that time was comparable to "chief of staff" in the White House today.

Democrats argued that Republicans won in Southwestern Virginia because they cheated regularly. The claim was that Republican operatives would collect absentee ballots in the Ninth District, using bribery to get voters to mark ballots as directed and a "black satchel" to gather the votes. Dishonest methods were used to record absentee votes, while county officials who belonged to the Republican Party were complicit in voter fraud. Republicans argued that electoral boards were controlled by Democrats, and cheated just as much as Republicans.3

Slemp's replacement was a Democrat, George Campbell Peery. He retired after three terms in 1928. The Ninth District replace Rep. Peery with a Republican for one term, then flipped again in 1930 and elected Democrat John W. Flannagan Jr. He served nine terms until retiring in 1948. Another Democrat, Thomas Bacon Fugate, was elected for the next two terms.4

In 1952, a Republican, William Creed Wampler, was elected to the US Congress to represent the Ninth District. Two years later, he was defeated in an election he claimed was stolen by voter fraud. Rep. William Pat Jennings represented the Ninth District until 1966, when William Wampler finally defeated him.

In 1982, Rep. William Wampler was defeated by Democrat Frederick C. Boucher. It was another election where the losers claimed fraud, citing voting irregularities with absentee ballots, tampering with voting machines, vote buying and intimidation.

The 1981 election of a Democratic governor, "Chuck" Robb, had altered the composition of the local electoral boards. For the previous 12 years when Republicans had served as governor, each local board had been composed of two Republicans and one Democrat. In 1982, the ratio was reversed. The voting process was controlled by two Democrats and one Republican. Undetected voting fraud by the Republicans would have been more likely since 1969, but similar fraud by the Democrats would have become easier in 1981.

In 1980, the US House of Representatives had investigated claims by Democrats that Boucher's close defeat that year was due to voter fraud. In 1982 a spokesperson for the Republican National Committee still claimed the local electoral boards in the Ninth District had run honest elections for a dozen years, saying:5

Rep. Boucher served until 2010. He was defeated in a "wave" election during the middle of President Obama's first term by Morgan Griffith, who had been the first Republican Majority Leader in the Virginia House of Delegates. Since then, the Ninth District has voted reliably for Republicans in local, state, and national elections.6

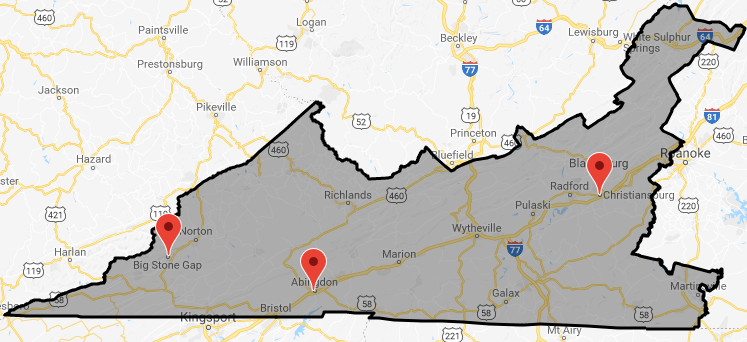

in 2018, Rep. Morgan Griffith had offices in Big Stone Gap, Abingdon, and Christiansburg

Source: Representative Morgan Griffith, Interactive Google Map

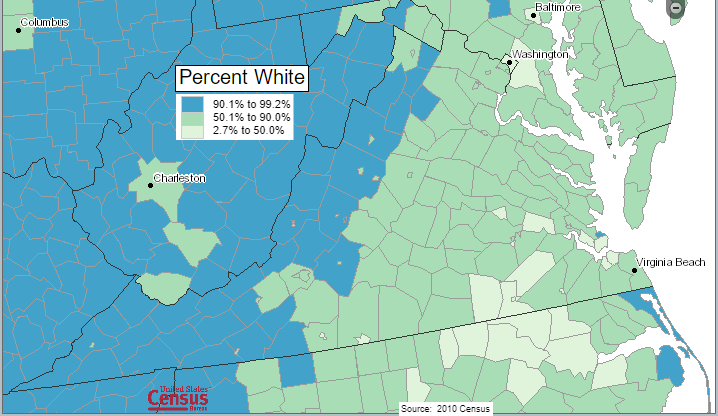

the demographics of the Ninth District are a factor in its shift to "Reliably Republican" today

Source: Bureau of Census, Census Data Mapper

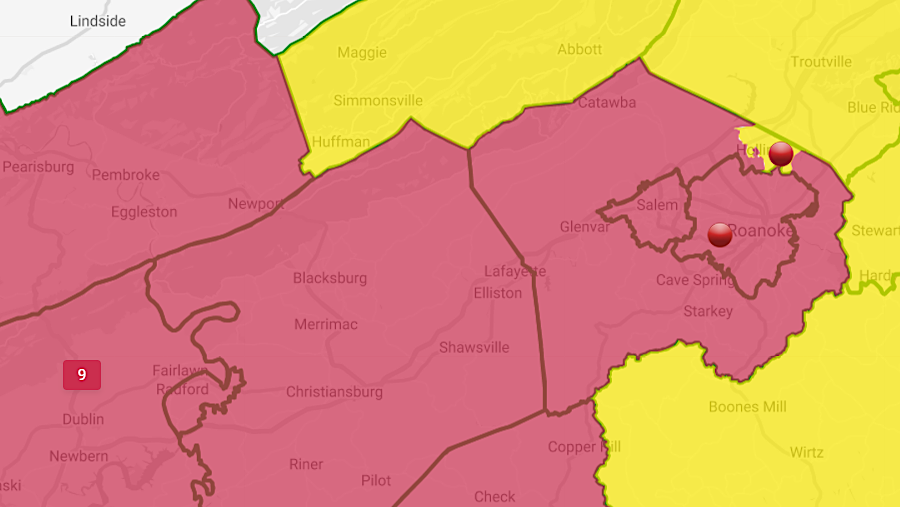

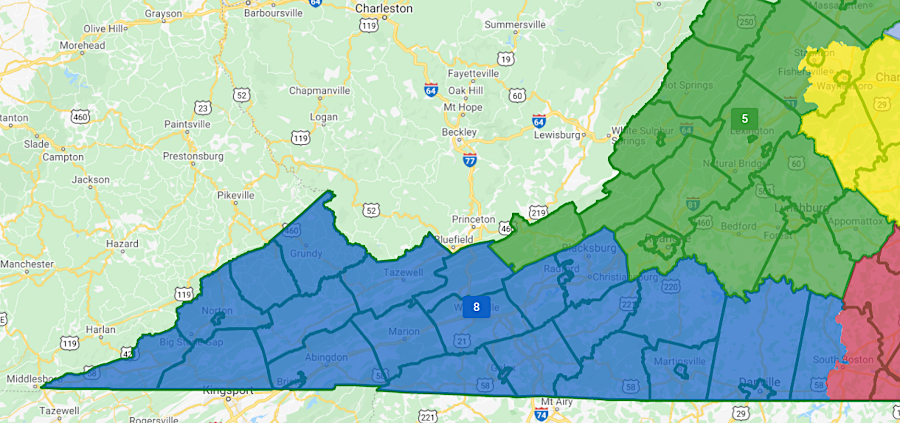

In the 2021 redistricting process, the Democrats on the Virginia Redistrictin Commission bargained with the Republicans,and each side ddrew the boundaries for three districts where elections were not competitive. Democrats drew boundaries for the 8th, 10th and 11th Congressional districts in Northern Virginia, which everyone predicted would elect Democratic candidates. Republicans drew boundaries for the 5th, 6th, and 9th districts, three reliably-Republican areas.

Population changes between 2010-2020 left the Ninth District needing to add 90,000 people to meet the one person-one vote standard; district boundaries had to be expanded. The major choices were to expand eastward along the North Carolina border, or to grow northeastward towards Roanoke and keep the district west of the Blue Ridge.

The Republican proposal was to incorporate Roanoke and much of Roanoke County into the Ninth District. The map moved Martinsville and part of Henry County out of the Ninth District and into the Southside-based 5th District, but proposed to retain the 17,608 people in Patrick County. Patrick County was contiguous, but would be the only jurisdiction east of the Blue Ridge in the Ninth District.7

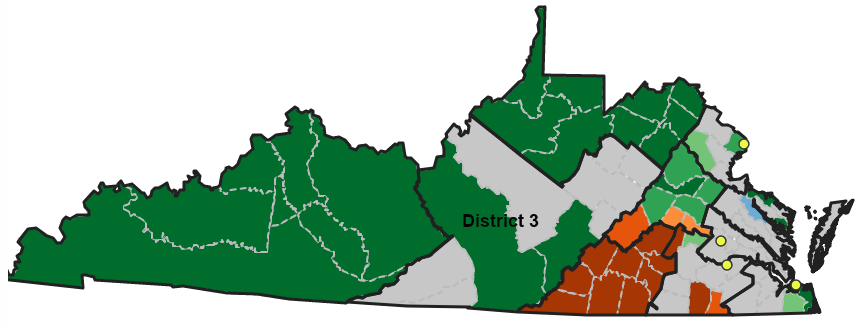

Republican map drawers proposed expanding the Ninth District to the northeast, but gerrymandered a corner of Roanoke County to be in the Sixth District (yellow)

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, VA Congressional House (Plan 364)

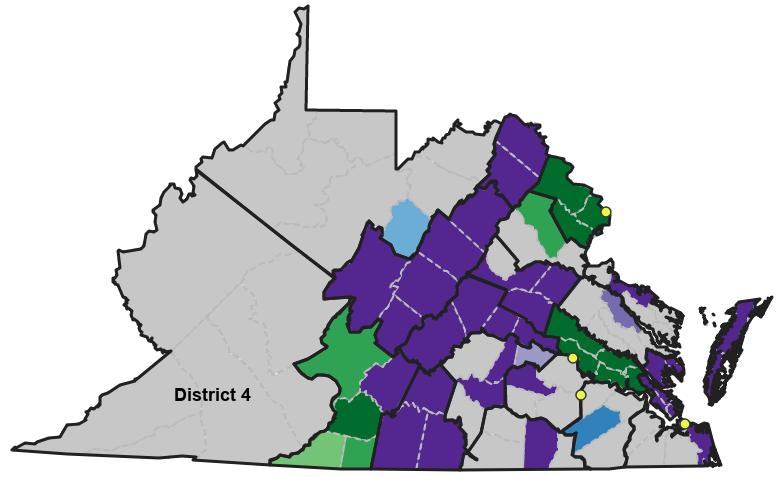

one citizen-submitted redistricting proposal expanded the Ninth District far to the east (and renamed it the Eighth District)

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, VA Congressional House (Plan 375)