colonial militia were local defense forces, often used to respond to Native American attacks

Source: National Park Service, New Archeological Discoveries at Moores Creek National Battlefield

colonial militia were local defense forces, often used to respond to Native American attacks

Source: National Park Service, New Archeological Discoveries at Moores Creek National Battlefield

England relied upon local militia rather than a standing army for land defense into the 1600's. As an island, it was less subject to a land invasion that other European nations which established full-time national armies in the mid-1600's. England invested primarily in the Royal Navy to block invasion by Spain or France, while European monarchs invested in standing armies.

The military revolution in Europe after the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia enabled monarchs to seize control of warfare from nobles who had previously directed their subjects to attack rivals. The nobles became leaders in the monarch's army, and the power of centralized governments increased.

Standing armies were better trained and better equipped than the militia and mobs that had previously conducted warfare, but more expensive to maintain. In England, however, the elite landowners who controlled Parliament remained reluctant to allow the king to decide when to declare war. Each war required higher taxes. Monarchs were constrained in their ability to get entangled in foreign wars because Parliament would not provide the extra funding required for a military "adventure."

Parliament continued to rely upon the Royal Navy plus the militia for defense against invasion. The elite blocked the creation of a standing army, fearing the king might use it to overpower nobles in England. The English Civil War in the mid-1600's demonstrated the threat. Making it necessary for monarchs to obtain Parliamentary approval to finance an army also limited the king or queen's ability to engage in foreign wars that lacked popular support. The monarch had power of the sword, but Parliament had power of the purse.

In 1688 the Glorious Revolution established the primacy of Parliament over the monarch; that became fundamental element in the unwritten English "constitution." A standing army became acceptable to England's power brokers so long as they controlled it, rather than a monarch who claimed unlimited authority. By the time of the American Revolution, England was dependent upon a professional army as well as the Royal Navy, and in England the militia became a marginal force.

In contrast, the colony of Virginia relied upon the local militia for defense up to the start of the American Revolution. The Virginia colonists were not wealthy enough to afford full-time soldiers or a navy. Nearly everyone was engaged in agriculture; they needed to be home, especially to plant in the spring and to harvest in the fall.

Opposition to a standing army mirrored the Whig perspective in England. Virginia's plantation owners welcomed their independence from oversight by London officials, and opposed the centralized control that a Royal Governor could exert through a standing army. No American colony maintained a standing army to deter attacks by Native Americans.1

The General Assembly began to meet in 1619, and it soon began to assign responsibility to local officials to serve as military leaders. After the creation of counties in 1634, the governor and his Governor's Council appointed county court justices of the peace to handle civil affairs. They appointed county lieutenants and subordinate officers down to company captains to manage military affairs. Local captains appointed sergeants and ensigns

The militia was organized by county, and the governor relied upon local leaders to identify who should serve as a county lieutenant. The men required to be part of the militia were reluctant to leave their chores to perform military duty; county lieutenants needed to be respected in order to assemble and lead the militia.

The Virginia General Assembly did hire rangers at times to patrol the backcountry. During the French and Indian War colonies creating "provincial regulars," the closest equivalent to the professional soldiers that developed in the English army. Provincial regulars enlisted for a term of service and were guaranteed pay for that period.

Recruiting such soldiers included promises of free land as well as the soldier's pay. Recruits were rarely the most-disciplined or hardest-working members in the county. Those enlisting for a bounty often arrived in camp without the required clothing, guns, powder, and ammunition.

Robert Carter was appointed to command the militia in Lancaster and Northumberland counties in 1720. He warned the governor not to appoint subordinate officers until Carter could determine who could be effective leaders in those counties:2

To assemble the militia to respond to threats, riders on horses would spread the word to various farms. The men would gather as needed, respond to the threat as commanded, and then return to their farms.

In theory, there were regular training sessions of the militia at the county courthouse. In times of peace, however, those sessions became largely social events. The County Lieutenant was often a candidate for the House of Burgesses, and strict discipline of essentially volunteer soldiers was rare. More often, the drinking during the militia assemblies was more intense than the target practice.

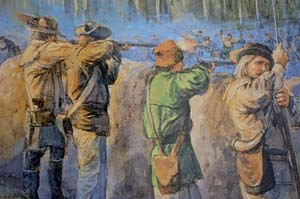

the Bill of Rights refers to a "well regulated" militia

Source: Library of Congress, Congress of the United States in the House of representatives. Monday, 24th August, 1789

In times of war, those with crops to plant and harvest were reluctant to serve for more than a few weeks. When a militia unit received orders to march to another colony, their reluctance was based in part on a desire to return home soon rather than a misguided allegiance to Virginia. Bounties attracted the "idle poor" who had less to lose, and were more willing to volunteer.

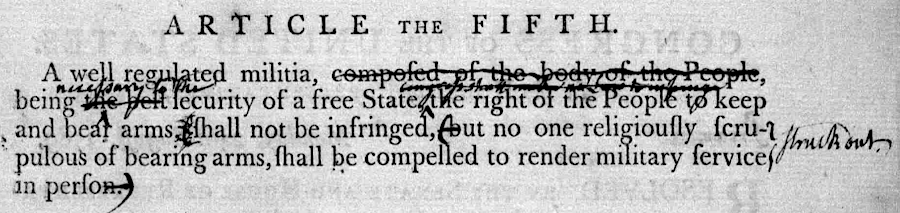

Virginia militia who fought at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781 are remembered on the visitor center's monument

Whatever equipment was issued to the militia had a tendency to be lost or damaged, but some items were obviously sold or kept for personal profit. The militia motivations were basic, with patriotism towards the colony not at the top of the list.

The earliest colonial alarms which triggered a militia response were created by threats from Native Americans. The General Assembly judged that the militia, together with scattered forts and "rangers," would be adequate to protect the plantation houses in Tidewater, but small farmers settling near the Fall Line felt too exposed. Nathanial Bacon was able to recruit an army in 1676 and rebel against the colonial government in part because Governor William Berkeley was seen as ineffective in providing homeland security.

in the 1660's the Virginia elite accepted a high level of risk regarding attack by the Dutch and by pirates in the Chesapeake Bay. The plantation owners were dependent upon transatlantic shipping for exporting tobacco and importing manufactured goods, but accepted the deployment of a small, under-gunned guard ship to the Chesapeake Bay after the Dutch had successfully captured the tobacco fleet in 1673.

A more-powerful guardship would have offered more protection, but also would have been more effective at collecting import and export duties. Pirates were able to overwhelm the 16-gun Essex in 1699, after which the 28-gun Shoreham was sent to Virginia.3

George Washington got his first experience as a military commander trying to defend the western edge of colonial settlement with provincial regulars and militia. His first portrait, painted in 1772, shows him dressed in the uniform of the Virginia Regiment of Provincial Regulars.

George Washington was an officer in the Virginia Regiment of Provincial Regulars

Source: Washington and Lee University, W&L, Mount Vernon Announce Mutual Loan of Washington Portraits

During the French and Indian War, George Washington struggled to obtain and trained enough soldiers for a sustained campaign. The provincial regulars, organized as the Virginia Regiment, were recruited through financial incentives that included promises of a future land grant. Governor Dinwiddie issued a proclamation on February 19, 1754 announcing that he had reserved for land bounties 200,000 acres on the east side of the Ohio River next to the fort at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers.4

One author has described the conditions of serving at the front (Winchester, in Frederick County) in 1757:5

Bedford County militia who fought at Point Pleasant in 1774 are commemorated by a plaque on the lawn of the county courthouse

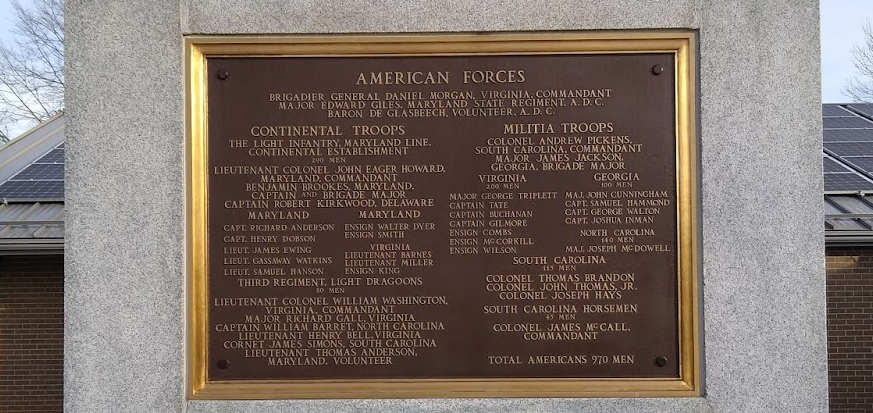

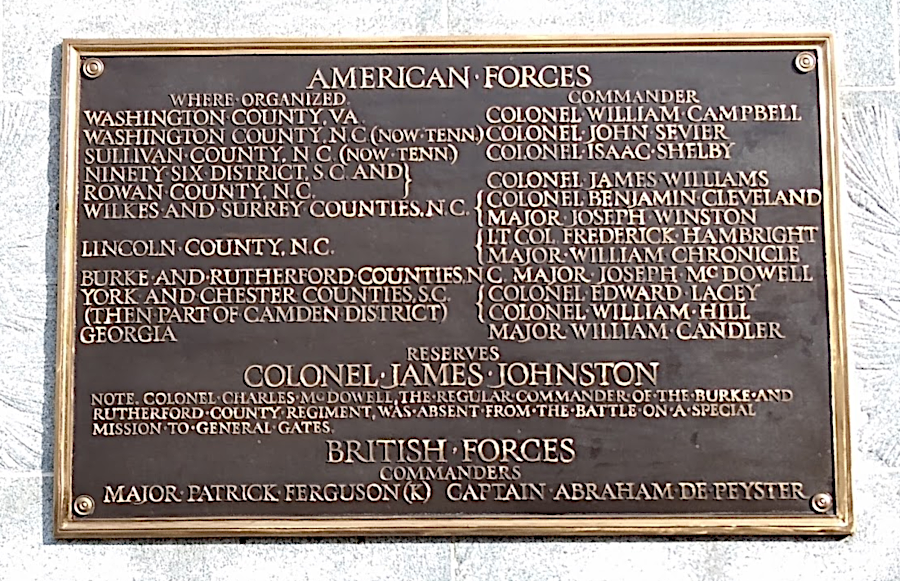

Virginia militia units, the Overmountain Men who fought at Kings Mountain in 1780, are remembered on a battlefield monument in South Carolina