Native Americans built palisades to protect towns in Tidewater Virginia

Native Americans built palisades to protect towns in Tidewater Virginia

The first fortified sites in Virginia were constructed by Native Americans who built wooden walls ("palisades") around their towns. Tree trunks and large branches were aligned to encircle the houses in a town, providing a defensive barrier. The palisades were designed for tribal conflicts that used bows-and-arrow technology.

Starting in 1607 at Jamestown, the English colonists initiated the construction of similar fortifications. The English desired protection against both the Native Americans and a potential attack by European ships armed with cannon. The colonists expected that if a Spanish ship ever sailed upstream past Hog Island, it would be coming to eliminate the English colony rather than to trade and exchange pleasantries.

The first fort built by the English colonists at Jamestown was not substantial. The initial focus was on exploration and discovery, not investing in defense.

Soon after unloading the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery, Captain Newport led an expedition upstream with over 20 men. On May 26, while the expedition was upstream, the Paspahegh attacked the new settlement at Jamestown. The English struggled to defend themselves, since their guns were still in storage. The attack was ended by cannon fire from the ships.

John Smith reported that one boy was killed on Discovery and 13-14 were wounded. After the assault:1

The incentive to work fast was obvious. Six or seven times during the construction, the Paspahegh lay in ambush. They managed to wound several colonists, one of whom died.2

George Percy reported that construction of Virginia's first substantial military fortification was completed within three weeks. It was based on a European design:3

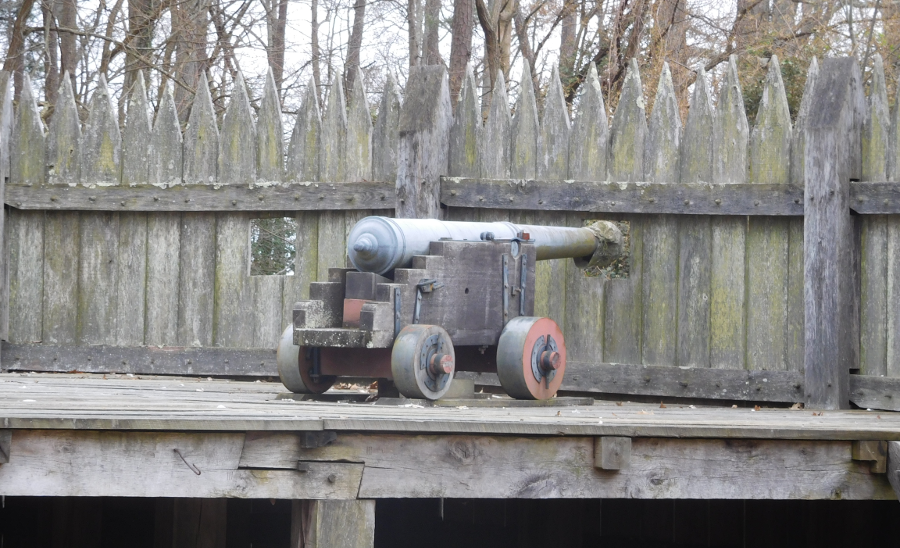

the English brought cannon to Virginia because they feared an attack by a Spanish ship, and the weapons did provide necessary protection against Native Americans

Powhatan sent representatives to the triangle-shaped enclosure, including Pocahontas, to trade and to spy on the uninvited newcomers. Gates in the wooden wall of "James Fort" allowed the colonists to control which Native Americans could circulate within the area occupied by the colonists, and when they could be there.

front gate of reconstructed fort at Jamestown Settlement, a tourism-based site operated by the state of Virginia since the 350th anniversary in 1957

The colonists did not isolate themselves inside their new fort; they too had a need for interaction. Engaging with the "naturals" gave the colonists some intelligence about the indigenous residents and about the area they planned to occupy. The English also needed food, and hoped to discover gold.

Discussions and bargaining occurred both outside and within the walls of the fort. William Strachey's secondhand account of a naked Pocahontas doing cartwheels inside the fort may not be accurate, but it does reflect the willingness of the colonists to allow Native Americans inside the fort.4

The cannon at "James Fort" were probably inadequate to prevent a successful Spanish attack, but no enemy warship sailed that far upstream and the defenses were never tested. The fort's wooden palisade did allow the English to control how many Native Americans were in the fort at one time, reducing the threat of a surprise assault on the ground. As revealed in the 1622 uprising, the colony's intelligence gathering capabilities - and analytical skills to anticipate an attack - were inadequate.

The second fort built in Virginia by the English colonists was at Point Comfort in 1609. The initial fort there was called Fort Algernourne (sometimes spelled Algernon). It sheltered 30 colonists who thrived on seafood during the Starving Time of 1609-10, when those living at Jamestown were so hungry that at least one settler resorted to cannibalism..

Fort Algernourne did not have cannon with sufficient range to block enemy ships from sailing up the James River, but did provide an early warning system to give Jamestown time to prepare for defense. Soldiers stationed there could also provide fresh water and support to English ships that had just crossed the 3,000-mile Atlantic Ocean and reached the Chesapeake Bay.

In 1610 Sir Thomas Dale attacked the Kecoughtans and forced them off their land near Fort Algernourne, initiating the settlement of Hampton. In 1611, Lord De la Warre had Fort Charles and Fort Henry constructed on either side of the Hampton River. Today the city of Hampton is the longest continuously-occupied site in North America established by the English.

Lord De la Warre also ordered construction of Fort West at the Fall Line of the James River "upon an Island invironed also with Corne ground." He lacked the boats and soldiers required to station people full-time at three forts, but had the infrastructure prepared in case of need.5

John Smith's map showing Point Comfort, site of Fort Algernon, Fort George, and finally Fort Monroe

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606

The next colonial settlements established after Jamestown and Hampton, including Bermuda Hundred and Henricus, were built on peninsulas starting in 1611. Sir Thomas Dale brought military discipline to the colony. He proposed the Virginia Company send 2,000 men so he could create five strongholds capable of resisting a Spanish attack.

Dale did construct new settlements such as Henricus and Bermuda Hundred. They were protected by wooden walls, built between riverbanks to protect from land attack by the hostile neighbors. The Native Americans in Virginia could use canoes to attack the river side of colonial settlements where no palisade had been constructed, but English placed cannons there for protection against European or pirate assault. Even without a triangular fort at the new settlements such as the one at Jamestown, the firepower facing the river was considered sufficient protection against potential amphibious attack by Algonquian-speaking warriors.6

palisade at Henricus reconstruction (note gaps between trees forming wall, in contrast to reconstruction at Jamestown where more labor was available)

The power of the Powhatans was broken in less than 50 years of English occupation. As the English established farms on the Peninsula, Middle Peninsula, and then finally the Northern Neck, the Powhatan lifestyle of living in winter hunting camps and summer agricultural towns was disrupted.

In 1622, Opechancanough led an uprising in response to the expansion of the colony onto territory that he controlled as the paramount chief in Tsenacomoco. In the two settlements south of the James River, Bennett's Welcome and Basse's Choice, 52 colonists were killed. In 1623 the English expelled the Warraskoyack from their traditional territory and built a fort called "The Castle" in Isle of Wight County.

It was named Fort Boykin when rebuilt by the rebelling colonists in the Revolutionary War. The fort was rebuilt and expanded again during the War of 1812 and the Civil War. Today it is a public park in Isle of Wight County.7

In 1633, a wooden palisade was constructed between the James and York rivers, passing through Middle Plantation (later the site of Williamsburg), in order to exclude Native Americans from the Peninsula.8

approximate route of 1634 palisade across the Peninsula, cutting through modern-day Williamsburg

Source: location of palisade from Phillip Levy, A New Look at an Old Wall. Indians, Englishmen, Landscape, and the 1634 Palisade at Middle Plantation

(overlaid on USGS 7.5 minute topo, 2010)

After the 1644 uprising, Opechancanough was captured and murdered while in English custody, and the English systematically destroyed Algonquian towns and cornfields. The remnants of Powhatan's political organization were fragmented, never to be reassembled.

After 1644, the main Indian threat to the English colonists in Virginia came from bands of northern Indians raiding into Virginia from Pennsylvania and New York. The 1646 treaty signed by Opechancanough's successor, Necotowance, required the Virginia tribes to be allies with the English against such raids. In 1656 the leader of the Pamunkey Tribe (Totopotomoy) was killed while fighting "Rickohockans" (perhaps offshoots of the Seneca tribe in western New York, or Cherokees from the Tennessee River watershed) at Bloody Run, in what is now the Church Hill area of Richmond.

Once the paramount chiefdom structure of Powhatan was destroyed, the primary interactions between the English and the remaining tribes in Virginia were based on the fur trade. When the English first arrived in 1607, Powhatan established his tribal organization as the "middleman" who would take a cut of the profits. Powhatan blocked the Siouan-speaking tribes west of the Fall Line from direct trade with the English at Jamestown.

Powhatan was not unique in this approach. In New England, the Iroquois tribes blocked the English from trading with the Hurons and others who lived further inland, and extracted high prices from the English for furs and skins until the American Revolution disrupted relationships.

The fur trade depended upon Native Americans harvesting a surplus of furs and food from their lands far from English settlements, and bringing the furs/skins to Tidewater settlements to trade with the English. In 1645, the General Assembly restricted trade between Native Americans and colonists to three forts.

Fort Charles was at the falls of the James River (modern-day Richmond). Fort Royall was located on the Pamunkey River on an island at the mouth of Totopotomoy Creek, near Opechancanough's capital. Those two forts helped define a perimeter west of the 1633 palisade. Fort James was located deep inside that perimeter at the confluence of Diascund Creek and the Chickahominy River.

In early 1646, the General Assembly authorized construction of Fort Henry (and 45 soldiers to staff it) at the mouth of the Appomattox River. In late 1646, after Opechancanough was captured and murdered, his successor Necotowance signed a peace treaty. The General Assembly then gave Fort Henry to its commander, Captain Abraham Wood, along with a land grant.9

In 1672, Governor Berkeley contracted with William Drummond to build a fort at Jamestown. The Third Anglo-Dutch War put the colonial capital at risk. Berkeley, one of eight Lords Proprietors that were awarded the Carolina colony by King Charles II in 1663, had appointed Drummond to govern the territory around Albemarle Sound.

Drummond did such a poor job of building the fort, and constructed it so slowly, that the governor had him arrested. The two ended up being political enemies. Drummond suported Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, during which Jamestown was burned.

The man contracted in 1672 to build a fortification to protect the colonial capital ended up helping to destroy it. When Governor Berkeley regained power, he had William Drummond executed soon after he was captured.10

Petersburg, Virginia developed from that fur-trading Fort Henry, managed after 1646 by Captain Abraham Wood. In 1650, Wood, Edward Bland, and seven others traveled southwest of the fort for nine days. Their mission was to establish trading relationships with the Native Americans on the Piedmont.

In 1673, Abraham Wood sent explorers James Needham and Gabriel Arthur further west. That expedition was intended to establish direct trade with the Cherokee in the Tennessee River watershed. Wood was trying to bypass the Occaneechee tribe. They acted as middlemen at the traditional trading post on the Roanoke River near modern-day Clarksville, until their town was destroyed in Bacon's Rebellion in 1676.

forts established in 1645 (in red) and 1646 (in yellow)

Map Source: US Geological Survey, National Atlas

Both sides benefited from the fur trading transactions. The English stayed east of the Fall Line, and the tribes west of the Fall Line got access to English metal products, textiles, and guns. The French found the fur trade to be sufficiently lucrative that they never sent large numbers of colonists to North America, The French chose to build relationships that increased trading, rather than occupying Native American land and creating an agricultural colony, in Canada, Louisiana, and the Ohio River Valley.

The colonial fur trade in Virginia was a rough business, as William Claiborne discovered in the 1630's. In addition to conflicts between tribes for control of the hunting territory, the English fought among themselves. Bacon's Rebellion in 1676 was triggered in part by rivalries between Governor Berkeley and his friends (who had been given special rights for engaging in the fur trade) and the out-of-power planters who lived at the edges of colonial settlement. The risks of living at the interface of English/Indian territory (the "frontier") were high, but the rewards were limited by Governor Berkeley.

Bel Air, perhaps the oldest building in Prince William County

Colonial policy on protecting the frontier from raiding northern tribes was not consistent. Frontier forts were built and then abandoned because of the cost of staffing them. Prince William County, now urbanizing as population growth in Northern Virginia continues to expand, was once on the frontier. The stone walls in the basement of the Bel Air house may be the remnants a 1670's fort that housed rangers assigned to the headwaters of various coastal streams. The rangers were looking primarily for hunting parties of Susquehannocks and Iroquois from New York. Such groups were considered more likely to raid English farms, since they had no local towns or farm fields to protect.

The alternative to fixed fortifications on the frontier was to hire rangers to patrol the territory. The rangers were less-than-perfect sensors, and northern raiders could slip into Virginia undetected. When Nathaniel Bacon's overseer was killed by Indians, he launched a rebellion against the establishment based in Jamestown, attacked the peaceful Indians who were allied with Governor Berkeley - and even burned Jamestown itself, before Bacon died and the rebellion fizzled.

site of Fort Christanna, 1714-1717

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Geographic Names Information System

In 1714, Governor Spotswood stimulated development of a fort at Fort Christanna, south of modern-day Lawrenceville in Brunswick County. At the time, it was the edge of British colonial power. The modern historical marker at the site calls it "The Farthest Western Outpost of the British Empire."

Spotswood intended to concentrate the fur trade with southern tribes at one location that could be controlled. A surprise attack in 1717 by Iroquois rivals, on the Native American groups he had gathered peacefully at Fort Christanna, damaged his strategy. However, his main opposition was rival Virginia traders who traded weapons and other products for furs and skins, independent from Spotswood's licensed trading program.

Source: Historic Forrest, Fort Christanna (1714 Virginia Fort)

For 130 years after the destruction of the Powhatan tribes, from the 1644 uprising to the intrusion into Kentucky in the 1770's, colonist/Native American conflicts on the Virginia frontier were triggered by trading rivalries between tribes as well as by Native American resistance to colonial settlement.

When English settlement crossed beyond the Fall Line and started to occupy the Piedmont in the early 1700's, there were few Native American towns remaining east of the Blue Ridge. New diseases brought from Europe had reduced the Native American population throughout Virginia. In the Piedmont, attacks from raiding Catawbas from the south and Iroquois from the north had emptied out much of the region between the travels of John Lederer in 1669/1670 and the arrival of a large number of settlers build farms 50 years later.

Virginia colonists built so few forts in the Piedmont when it was the "frontier," the zone in the backcountry where colonial and Native American occupants clashed, because there was only a minimal Native American threat once colonial settlement moved west of the Fall Line. In the 1722 Treaty of Albany, the Iroquois agreed to travel west of the Blue Ridge when passing through Virginia.11

Starting in the 1730's, colonial occupation of the Shenandoah Valley disrupted Native American hunting patterns but apparently did not result in large-scale displacement of Native American villages in the valley. Tribes had already migrated out of the area, abandoning the towns which had been occupied since the adoption of agriculture. The threat to settlers west of the Blue Ridge came from occasional traveling bands of Cherokee and Catawba during raids on other tribes, and from Shawnee, Delaware, and Mingo who lived in the Ohio River Valley. In the French and Indian War, the Shawnee attacked plantations from Winchester south to the New River. Later in the American Revolution, the British sponsored such raids.

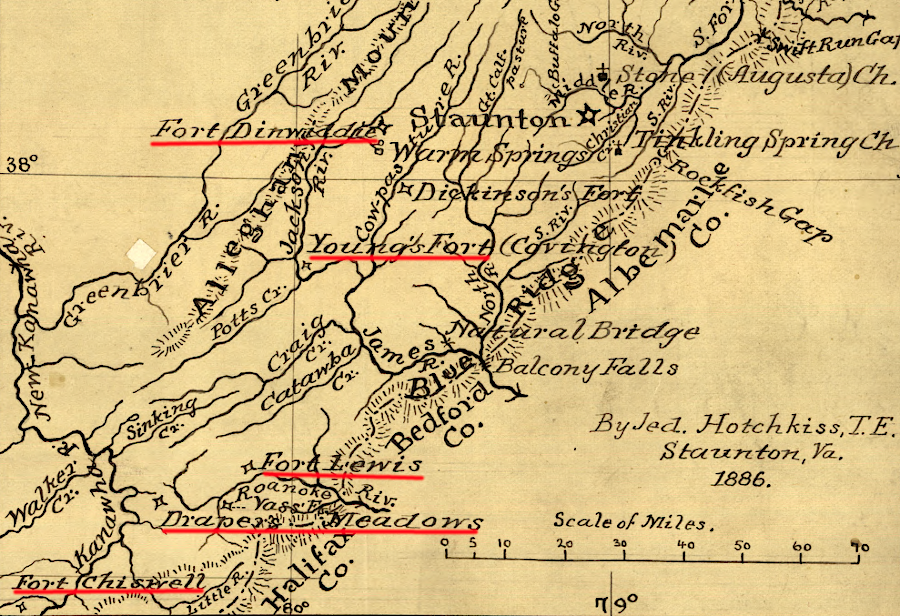

French and Indian War forts west of the Blue Ridge, between the New and Shenandoah rivers

Source: Library of Congress, Map of part of Augusta County, Colony of Virginia, 1755-1760

The General Assembly in Williamsburg did not fund construction of forts and a standing army to staff them west of the Blue Ridge except during the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. Colonists living in isolated farms west of the Blue Ridge built sturdy wooden houses that also served as defensive structures rather than facilities dedicated to just military protection. Such houses are called "forts" in many reports written in colonial days, especially after settlement reached the Shenandoah Valley. Nearby families would gather for common protection at fortified houses when there was a specific alarm that a war party was nearby.

Those frontier forts have disappeared over time, except for one discovered in 2019. A lawyer with a personal interest in Virginia's frontier forts recognized that the historic Byrnside-Beirne-Johnson House near Union, West Virginia could have been constructed around Byrnside's Fort. The fort had been built in 1770, when the Shawnee still disputed control over the borderlands of Virginia.12

Source: Civil Rights Lawyer, I Found a Revolutionary War Log Fort Inside a House

Byrnside's Fort, obscured until 2019 inside the historic Byrnside-Beirne-Johnson House, was located next to a spring emerging from a cave that provided drinking water in 1770

Source: X (Twitter), The Civil Rights Lawyer