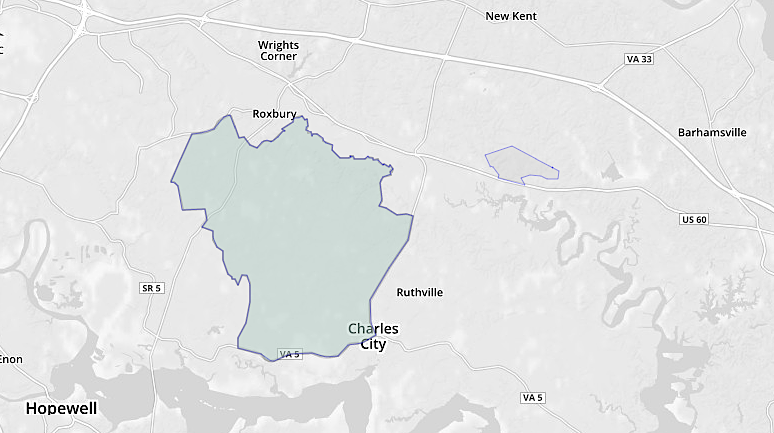

the center of the modern Chickahominy community is in a rural area of Charles City County

Source: Google Maps

the center of the modern Chickahominy community is in a rural area of Charles City County

Source: Google Maps

The Chickahominy were independent of Powhatan's paramount chiefdom in 1607. He appointed the weroance who governed each of the surrounding tribes, including the Paspahegh who lived at the mouth of the Chickahominy River, but Powhatan had no role in selecting the elders ("mungai") who governed the Chickahominy. Powhatan chose to expand his territory to the east, conquering the Kecoughtan and Chesapeakes, while accepting the independence of the Chickahominy in the center of Tsenacommacah.1

There were approximately 1,500 Chickahominy when the English arrived. Like others in the Woodland Period, they relied upon farming for food in the summer and fall, and depended upon hunting, fishing, and gathering for a portion of the year. "Chickahominy" supposedly means "People of the Coarse Pounded Corn."2

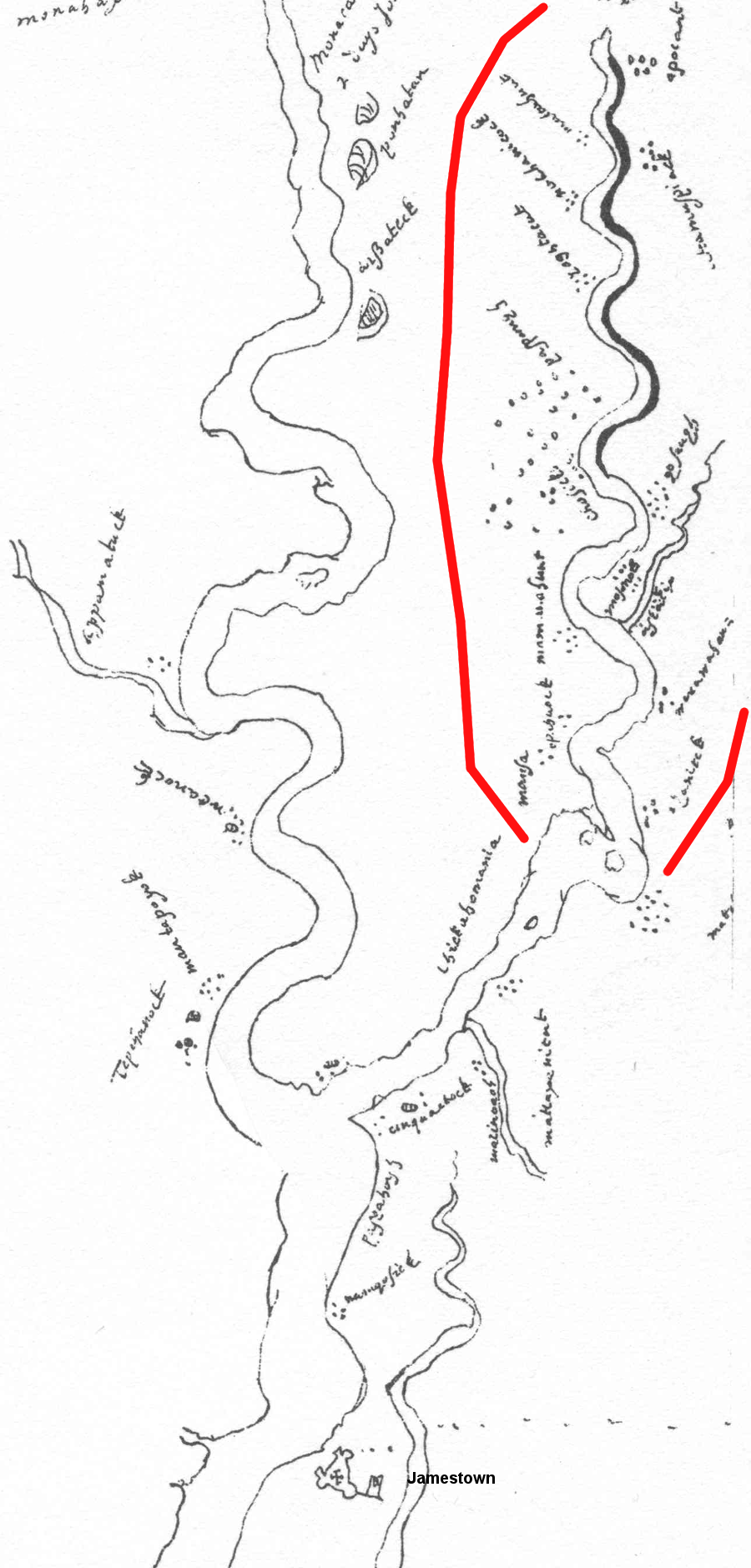

They lived in 15-20 towns, located on both sides of the Chickahominy River near the marshes that protected them from attack and supplied so much food:3

the Chickahominy controlled independent territory in the heart of Powhatan's Tsenacommacah

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

John Smith visited the Chickahominy in November, 1607. He calculated that Jamestown had only enough food remaining for two weeks. The English had already traded with the towns along the lower James River for their available corn, and by this time the Pasapaheghs living at the mouth of the Chickahominy River were a "churlish and trecherous nation." Smith decided to sail past them and trade with towns further upstream.

He took eight men on the barge, plus another seven men on the pinnace Discovery because he planned to acquire a major stockpile of corn for the winter. He found the Chickahominy eager to trade for copper and hatchets. He kept moving upstream to seek better deals and to explore the unknown territory.

He was the first to describe a Chickahominy town:4

in November 1607, John Smith met 200 Chickahominy in the "hart" of their country at Mamanahunt, where he traded for corn

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

He returned again to acquire more corn, then went up the Chickahominy River a third time past Apocant, "the highest Towne inhabited." The river grew so narrow he had to abandon the barge and move upstream in a canoe hired from the locals. On this third trip to trade with the Chickahominy and explore their territory, Smith was captured by a hunting party. After being dragged around Tidewater, Smith ended up at Werowocomoco and was "rescued" by Pocahontas.5

The Chickahominy were not spared during the First Anglo-Powhatan War in 1609-14. In 1610, George Percy led 70 men in two boats to attack them and the Paspahegh. The English landed near the mouth of the Chickahominy River, surrounded the town of the Paspahegh, and "putt some fiftene or sixtene to the Sworde and almoste all the reste to flyghte."

The English seized the wife and two children of the weroance Wowinchapuncke, then executed them on the trip back to Jamestown. The Paspahegh abandoned the area by 1611, and the raid made clear to the Chickahominy that the English could expel an entire group of people from their homeland.

The most-open hostilities of the First Anglo-Powhatan War ended after Pocahontas married John Rolfe in 1614. Powhatan focused on managing the remainder of Tsenacommacah not occupied by the colonists, and extracting whatever trade goods he could obtain from the Tassantassas (strangers) during a period of relative peace.

The Chickahominy chose to make a separate peace with Sir Thomas Dale in 1614. They agreed to acknowledge they were subjects of the English, to provide bowmen if the colonists were attacked by the Spanish, and to supply corn annually. The English agreed not to displace the Chickahominy from their traditional territory along the river, to provide "Copper, Beades, Hatchets, and many other necessaries, to "permit them to enjoy their owne liberties, freedoms, and lawes, and to be governed as formerly, by eight of their chiefest men," and most importantly "to defend and keepe them from the fury & danger of Powhatan.7

By 1616, the Chickahominy hedged their bets. They began sending a representative to meetings held by Powhatan. After Opechancanough organized an assault in 1622, the colonists raided through the towns and cornfields of the Chickahominy.8

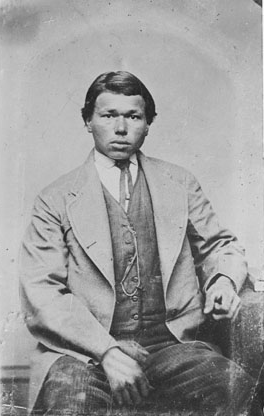

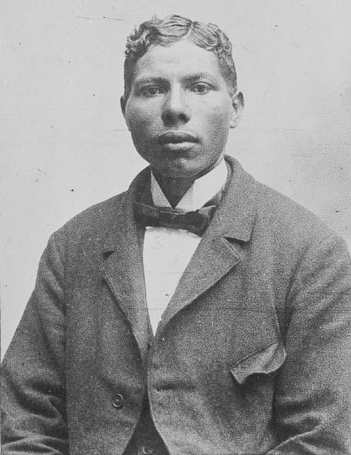

Chief William H. Adkins in 1901 and 1905

Source:

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Portrait (Front) of Chief William H. Adkins June 1901 and June 1905

The Chickahominy opened their annual Chickahominy Fall Festival & Pow Wow to the public in 1951. The greatest concentration of the Chickahominy today live on the ridge in Charles City County that separates the Chickahominy and James Rivers.

There are 900 members of the tribe. To be a member of the tribe requires tracing ancestry back to a list of members (tribal roll) compiled in 1901. The 12-member Tribal Council includes the tribal chief, a first and a second assistant chief, and nine tribal members. They serve four-year terms, staggered so the entire council is not replaced at once.9

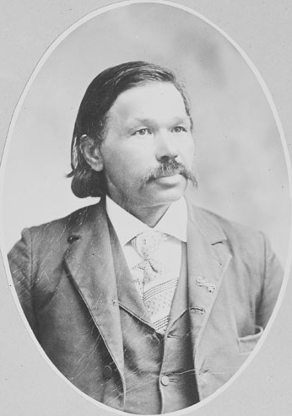

In 2019, the tribe acquired 105 acres on the north bank of the James River, just upstream from Lawrence Lewis Jr. Park in Charles City County. The $2.6 million purchase was funded by mitigation funding required for Dominion Energy to build the Surry-Skiffes Creek Transmission Line across the James River, since that project impacted a historical viewshed.10

in 2019, the Chickahominy acquired 105 acres on the James River near Weyanoke

Source: Virginia Outdoor Foundation, VOF Conservation Land

the Chickahominy now own waterfront property on the James River

Source: Charles City County Assessor

In 2021, the tribe received an additional $3.5 million from the General Assembly for land acquisition. Chief Stephen Adkins stated:11

After purchasing a 944-acre tract that included the historical town location of Mamanahunt, Chief Adkins emphasized that the location of the parcel on the Chickahominy River was especially important:12

Governor Ralph Northam highlighted the equity aspects of the land purchase:13

When the Chickahominy Tribe reacquired Mamanahunt in 2022, the river still had a stand of wild rice and arrow arum (tuckahoe) was common in the wetlands. However, the water was not as pristine as in 1607. "The Chick" was a popular site for anglers, but mercury pollution caused the Virginia Department of Health to post warnings about consuming fish. Additional health warnings were added in 2025 because perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) levels were excessively high.14

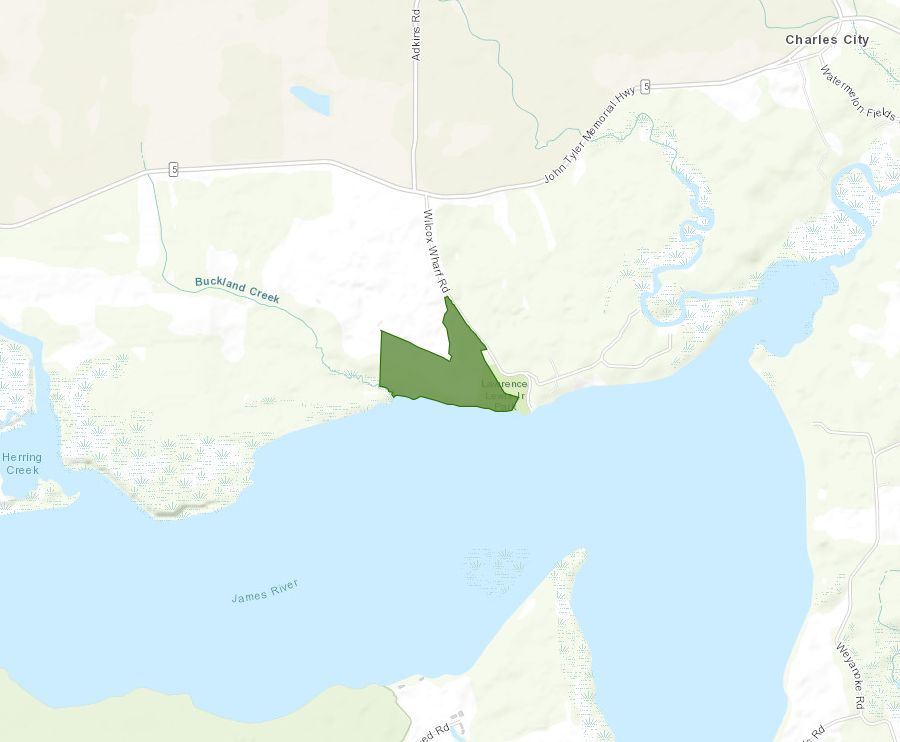

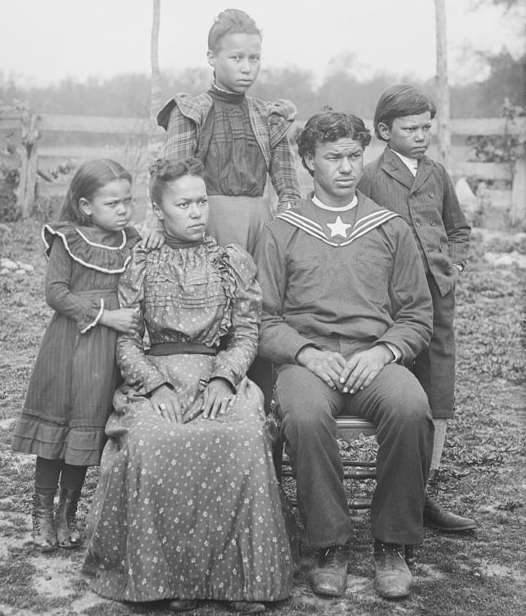

in 1901, the Chickahominy dressed up for photographers just like their neighbors

Source:

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Six People near Wood Frame Building 1900

three members of the Chickahominy in 1900

Source: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Woman and Two Boys near Wood Frame Building

James Mooney, from the Bureau of American Ethnology, documented Chickahominy life in 1900

Source: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Group of Five near Wood Fence, One in Military Uniform?

Chickahominy adults in 1900-1901

Source: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Portrait (Front) of Benjamin Adkins JUN 1901 and Woman near Tree 1900

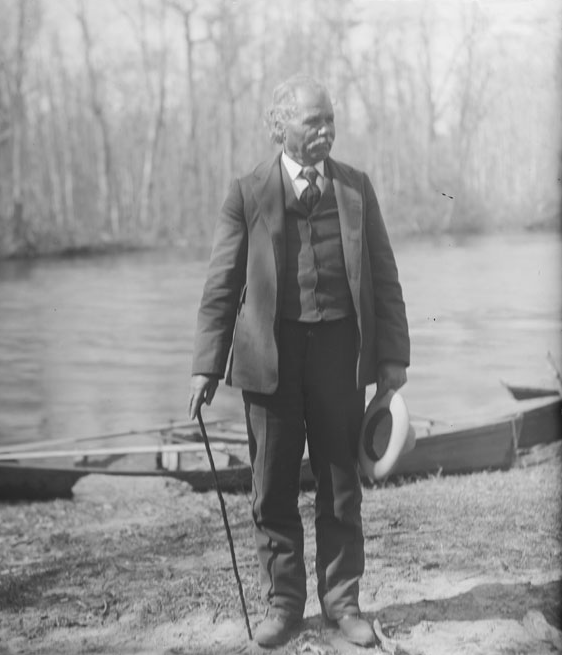

Chickahominy man with boats in background

Source: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Man near Row Boats in River 1900

the Chickahominy have always relied upon fishing as well as hunting

Source: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Four Men Fishing from Boats 1900

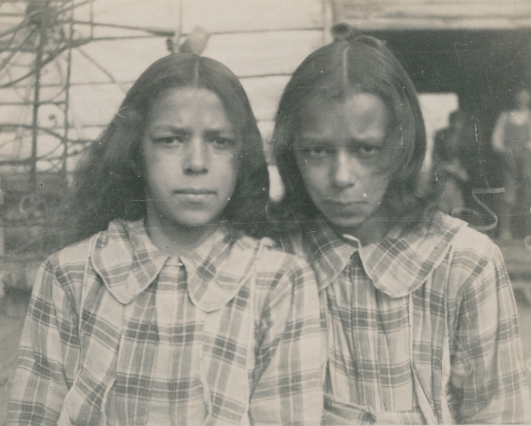

anthropologist Frank Speck photographed Winona and Iola Bradby in Providence Forge around 1900

Source: Virginia Humanities, Virginia Indian Archive, Aerial Image, Mantle Tribute to Virginia Indians

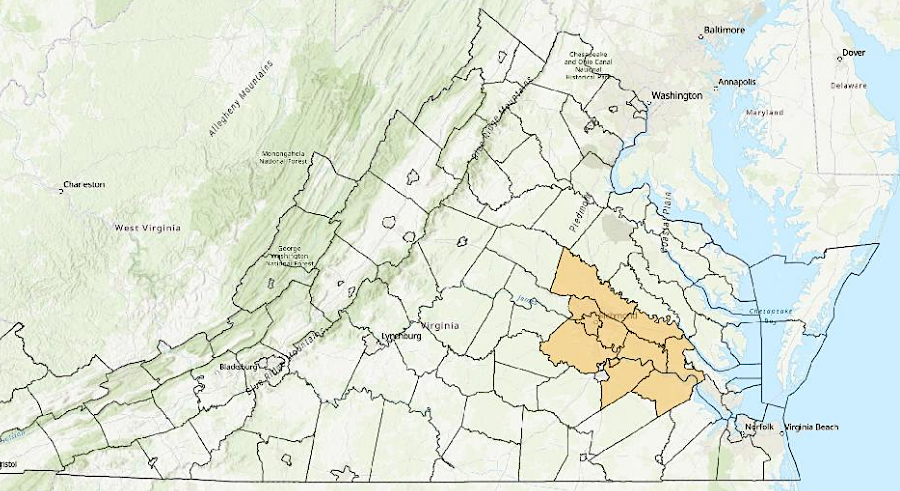

Chickahominy State Designated Tribal Statistical Area (SDTSA)

Source: Census Reporter, Chickahominy SDTSA

when the English arrived in 1607, the territory of the Chickahominy was not part of Powhatan's Tsenacommacah

Source: She-philosopher.com, The "Zuniga Chart" of Virginia, 1608

Virginia has defined a geographic area where the Chickahominy tribe should be consulted on state projects

Source: Secretary of the Commonwealth, 2025 Report Localities for Tribal Consultation