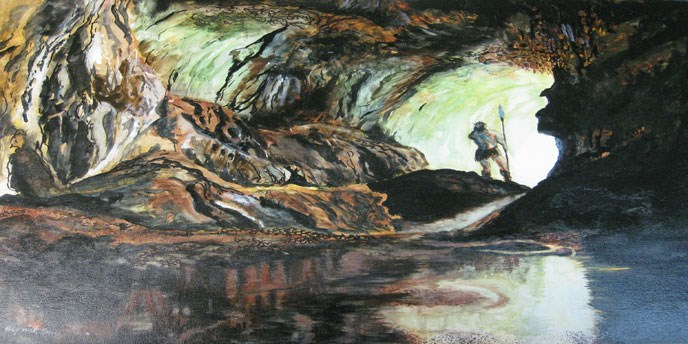

Native Americans used sandstone ledges and caves for shelter, and carefully selected different types of rock to make tools

Source: National Park Service, Russell Cave National Monument

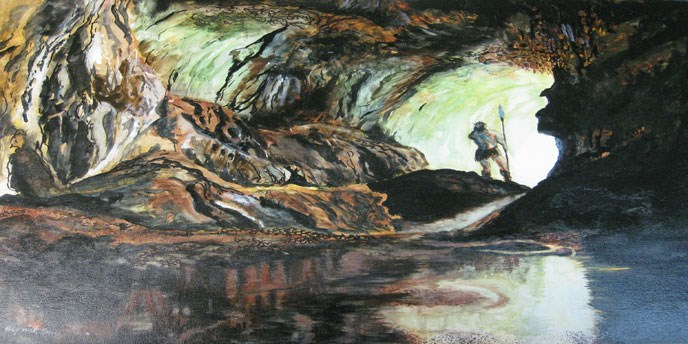

Native Americans used sandstone ledges and caves for shelter, and carefully selected different types of rock to make tools

Source: National Park Service, Russell Cave National Monument

The First Virginians did not arrive empty-handed. They brought small bundles of tools manufactured from rocks, as well as antlers, bones, shells, and wooden sticks. The oldest stone points found south of the Wisconsin ice sheet are 16,000 years old.

Fairfax Public Schools, Bone Tools used by Virginia's First People

Points is the generic term for most artifacts that could have been used as weapons. Knives and scrapers describe sharp-edged tools used to dismember animals and prepare hides for clothing. Awls are pencil-sized tools with sharp points used to drill points in hides for sewing or decorating. A close look at many items called "arrowheads" will reveal they are too heavy to be associated with arrows, but could have been used on spears of some sort.

Points, knives, and scrapers were manufactured from bone, wood, or by flaking chunks of carefully-selected stone. Using percussion and pressure, chips of rock were removed to create a sharp edge. Edges grew dull quickly, so Native Americans continuously improved their skills by constantly re-working or replacing their tool kit.

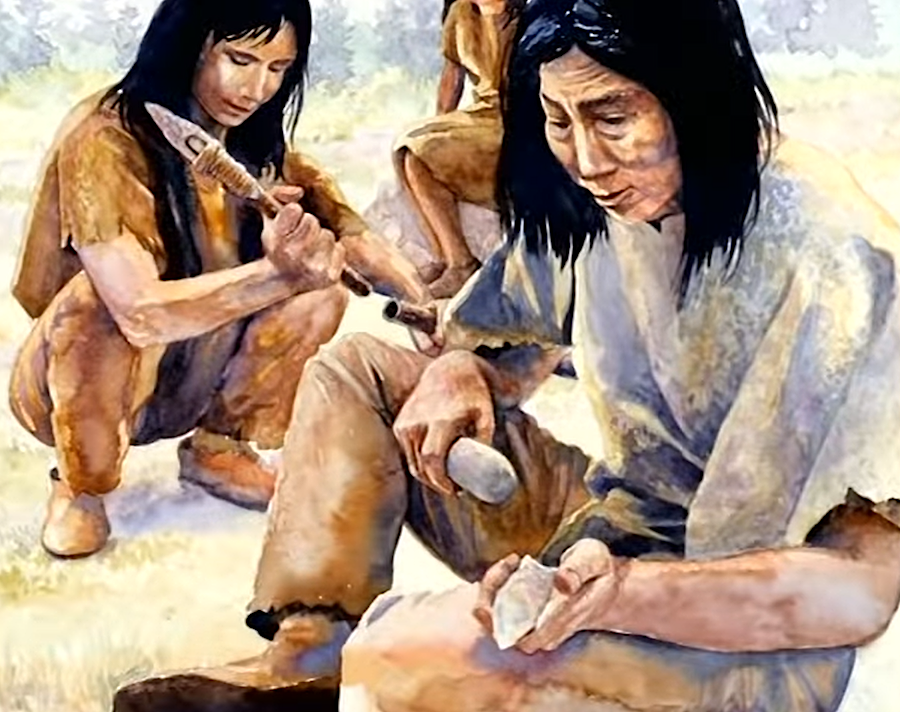

shaping rocks to make points of desired size/shape required skills that very few Americans have today

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, VDOT: Discovering the First Virginians

Axes, weights for fishing nets, and atlatl throwing stones were manufactured by grinding as well as chipping. Even bowls were made from stone.

The rock tools of Native Americans have a high percentage of quartz (silicon dioxide, SiO2). When quartz crystallizes in various cryptocrystalline forms such as jasper, chert, flint, quartzite, or even silica-rich metarhyolite, the rock fractures to form sharp edges.

Modern Virginians who depend upon silicon-based computer chips to perform specialized jobs might not be able to recognize quartz veins in sandstone, or distinguish jasper from basalt. When "primitive" people first wandered across Virginia 15,000 years ago looking for food, they were already savvy about silicon.

Native Americans used a variety of techniques for converting various types of quartz-rich rocks into specialized tools. Sharp edges were crafted by different techniques to chip the edges on one or two sides of a cobble or rock, to create axes, knives, choppers, spear points, drills, hammer stones, etc.

The first to arrive used larger stone tools, thick in the middle. Clovis and other early points could be retouched as the edges wore down. Recycling stone brought into a new territory reduced problem of being unfamiliar with the landscape. Reuse ensured tools would be available despite the lack of knowledge about where stone outcrops could supply new material.

As the Paleo-Indians gained knowledge, they adopted lighter tools. The capacity to rework a damaged point was reduced because the smaller blocks of stone had to be discarded more often when damaged beyond repair. However, the Native Americans knew where to go to obtain new raw material.

first explorers into new territory brought large points that could be retouched, then shifted to making lighter points after discovering where new stone could be quarried

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Clovis

Native Americans sought out the best material for their tools, but preferences changed over time as specialized tools were developed for different circumstances. Some groups used jasper, others used quartzite or metarhyolite, but all had a specific mineral structure which created sharp edges when fractured. Modern glass Coca-Cola bottles have a similar structure, and in the 1600's Native Americans manufactured points from glass obtained from colonists.1

The oldest mine in North America dates back 13,000 years. Paleo-Indians mined red ocher (hematite, a form of iron oxide) at a site now called Powars II in eastern Wyoming. The red ocher was used as a body paint, and provided some value as sunscreen. The red ocher was also be used as a pigment for painting on rock walls, and to decorate burials.

The trading patterns in prehistoric America were extensive. Stone was obtained from many miles away, even though local forms of quartz might have been worked into tools. Volcanic obsidian does not exist naturally east of the Mississippi River, but obsidian from Utah, Idaho, Oregon, and California has been found in New Jersey. Paleo-Indians who lived at the Shoop site near the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania used Onondaga chert from New York perhaps 150 miles away.2

Changes in tool making materials and techniques can provide insight into the population patterns of the past. Native Americans in Virginia never developed writing, so the story of Virginia's people prior to European contact in the 1500's is based on interpretations of the archeological record. Most items made from organic material (baskets, clothing, houses) has decayed, but the stone tools remain largely unchanged in the soil until discovery by farmers after rainstorms in plowed fields, bulldozer operators clearing a site for a new road/house, looters seeking artifacts, or archeologists seeking information.

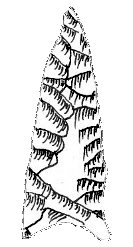

stone chipped to create sharp edges, developed in Paleo Period and suitable for spear tip to penetrate thick hide of a large mammal

Source: US Forest Service

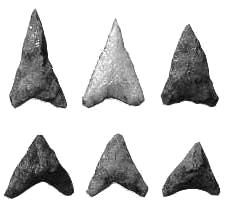

notched point, developed in Archaic Period

Source: National Park Service

small triangular points, developed in Woodland Period and suitable for arrowhead tips

Source: National Park Service

When archeologists discover a new type of stone tool at a site, debate begins on whether the occupants of that area evolved a new technique, learned a new technique from neighbors - or whether a new group of people moved into the territory. New occupants may have settled in an abandoned area, two communities may have integrated peacefully, or one group could have completely displaced the previous residents by force.

The stone itself offer a clue. In what is now Ohio, geochemical analysis shows that 12,900-year-old stone artifacts from the Clovis period were made from rock excavated nearly 300 miles away. The exotic blue-gray chert may have been quarried in one place and carried that long distance by the same people migrating eastward. It is also possible that a Paleo-Indian band made a special trip, traveling west those 300 miles in order to extract the specialized chert. A third option is that the stone was traded eastward through intermediaries.

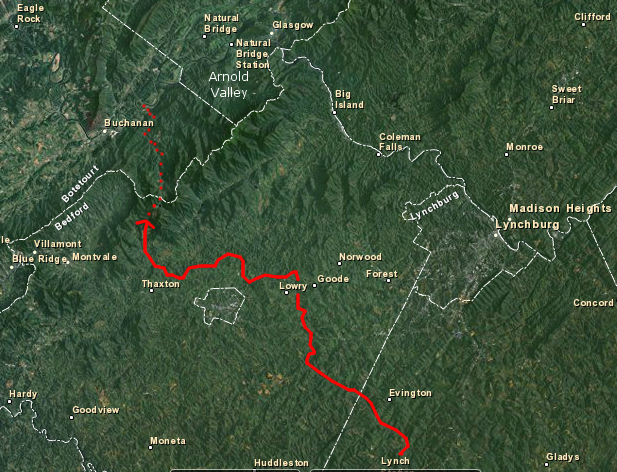

In Virginia, Archaic Period artifacts were found at a Peaks of Otter site when Abbott Lake was drained in 2008. The tools were made from quartz and argillite found in the Piedmont to the east, not jasper from the Ridge and Valley province to the west. That pattern suggests that, perhaps 5,000 years ago, a band of Native Americans living in the Roanoke River watershed near modern Bedford or Altavista followed the Big Otter River upstream on a hunting expedition.

It is possible that they kept moving uphill, using Stoney Creek as a guide as well as a supply of drinking water, then established a temporary camp near the crest of the Blue Ridge next to a wetland that is now dammed and drowned to form Abbott Lake. Those ancient hunters probably traveled further west to the James River near modern-day Buchanan. There they may have traded with one or more bands of hunters who had quarried the jasper outcrops (site 44RB323) in the Arnold Valley near Natural Bridge.3

possible travel route of hunting band 5,000 years ago in Archaic Period, based on types of rock used for tools and found at Peaks of Otter in 2008

Source: base map from US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

The earliest stone quarries used by Paleo-Indians in Virginia have been found at Flint Run in Warren County and the Williamson site in Dinwiddie County. At those sites, Native Americans pried chunks of cryptocrystalline quartz away from the less-useful limestone in the area. The quartz had crystallized several hundred million years earlier from silica-rich fluids that had penetrated geologic faults.

The initial chunks quarried from the bedrock were rarely in the correct shape to be useful without further processing. Large piles of waste rock chips were left behind at or near the quarries - a clue used thousands of years later to identify the location of ancient quarries. On the Coastal Plain, cobbles in streambeds provided the raw material for conversion into stone tools.

Converting rocks into tools required substantial time to chip off edges, starting with a step called "preliminary lithic reduction" to convert raw stone into cores or preformed blanks. Those chunks of rock could be carried away and refined by additional chipping into knives, blades, and various forms of "points."

The cores were portable, but nowhere close to a finished product. Cores were processed further at sites located away from quarries. Carrying the cores required carrying extra rock, but moving may have minimized conflicts with others coming to the quarry to obtain raw stone.

in 2019, sharp-eyed archeologists at Strawberry Run in Alexandria spotted quartzite cobbles manufactured in the Archaic Period into preform cores

Source: Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, What’s THAT Doing HERE? Unexpected Discoveries at the Strawberry Run Site in Alexandria, Virginia

Work stations where cores were converted into useful tools are often found near water sources. It is possible that everyone in a Paleo-Indian band made their own points for a season of hunting. Some with unusual talent may have become specialists and supplied points to others in a hunting band or for trade with a different group, but everyone needed stoneworking skills to ensure survival.

Individual points were resharpened after use. Sharp edges were essential for spear points to cut through the hides of game animals, blades to sever plant stalks easily, and drills to create holes for manufacture of clothing and cooking containers. Small scatterings of broken rock chips, where hunters resharpened their stone tools, may be found at many sites far away from the quarries.

Modern tourists at a scenic overlook may find stone flakes in the dirt near their feet. Visitors have admired the same scenery for the last 15,000 years, and some may have repaired a tool that was damaged during a hunt while enjoying the view. The appreciation of overlooks is not a new concept, developed only after automobiles facilitated modern tourism.

Once a resharpened point became too small, it was discarded. When too many tools had been broken or dulled, the band would return to a quarry to acquire more cores and restock the tool kit.

Fairfax Public Schools, Stone Tools used by Virginia's First People

All stone and bone tools were carried on the "seasonal round" as bands followed the migrations of animals and the ripening pattern of plants, so the weight of the tool kit was limited. If needed, local rocks could be used for temporary tools, but a Paleo-Indian band might have planned to visit each of its preferred quarries once a year.

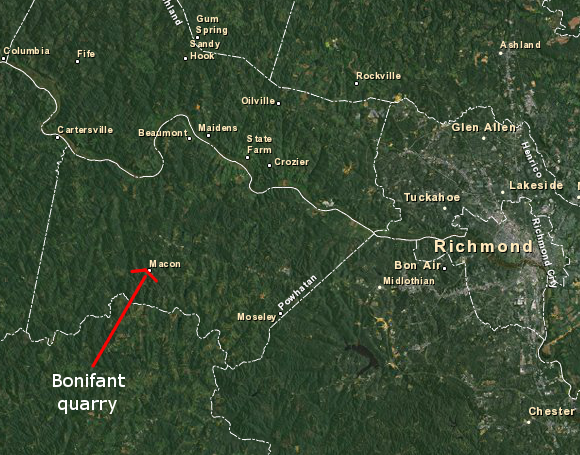

Bonifant/Bonnefont jasper is found as nodules in creeks near Macon (Powhatan County)

Source: background map from US Fish and Wildlife Service Wetlands Mapper

In Virginia, sources of jasper used for prehistoric stone tools include Flint Run (Warren County - site 44WR12), Brook Run (Culpeper County - site 44CU122), Arnold's Valley (Rockbridge County - site 44RB323), Bonifant (Powhatan County - site 44PO132), and sediments with eroded and transported cobbles in Virginia Beach (site 44VB5) and Accomack County (site 44AC136).4

The Powhatan County site, also called Bonnefont, was discovered after examination of a nearby archeological site revealed such a large amount of debitage (chips of waste rock, created as cores were converted into tools). The stone debris at Bonifant alerted archeologists that there could be a local source of high-quality stone in the area. Further searching led o discovery of the quarry site.5

The Flint Run complex in Warren County developed around 9,500BC. The jasper was quarried near the mouth of Flint Run, then carried across the South Fork of the Shenandoah River to the Thunderbird and Fifty sites and processed further on the other bank, perhaps during the winter when the river was frozen over. The Fifty site was close to a wetland that may have provided food, while the Thunderbird base camp faced south and was sheltered from the strong winds of that era.6

At the Thunderbird base camp, excess rock was chipped off to produce chunks suitable for later processing into blades and points. The prehistoric stone masons produced cores of good jasper/chert, the stone that flaked in the right pattern to form useful points with sharp edges.

Paleo-Indian and Archaic stonesmiths refined those chunks later (at locations away from the Thunderbird site) to create the spear points, drills, scrapers, cutting instruments, etc. Since more than one tribal group used the same quarry, there was logic to decision of different groups to grab-'n-go after initial processing to create cores, rather than linger around a place where conflict could occur to produce the complete toolkit.

However, the quarry may have been an intentional place for different family-sized groups to meet. There, they could trade items (such as rare shells that provided status), share information about good hunting/gathering places that year, and choose partners from outside the family. Every Paleo-Indian band needed to resupply their stone tool kit, so gathering at the quarry may have been the most logical place.

In the later Archaic Period, when Native Americans used a wider range of rock to make tools, gathering places were areas of rich biological productivity. Food became a stronger attraction than geology. Further north in Pennsylvania and New York, gathering places may have been associated with hunting camps for caribou, since those hunts were probably more successful when more than one family group participated.7

Thunderbird was used as a quarry for 4,000 years. That makes the site at the mouth of Flint Run the first and the longest-used industrial site in Virginia.8

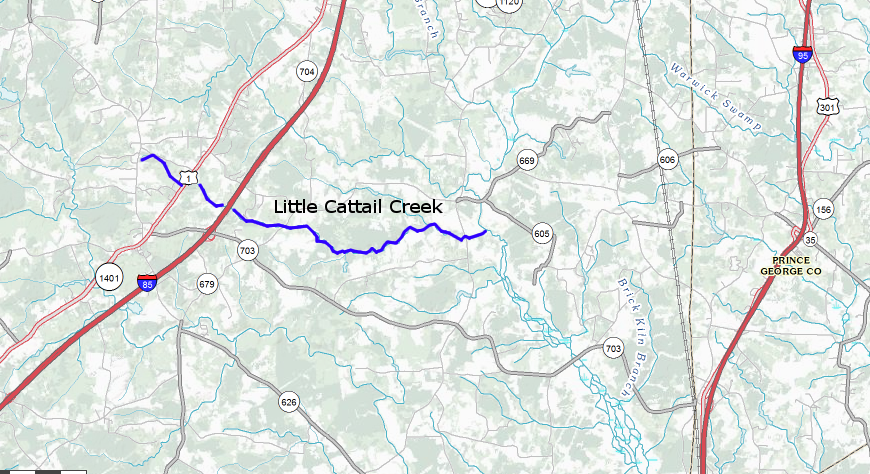

the Williamson Site is located above the Fall Line on Little Cattail Creek in Dinwiddie County

Source: US Geological Survey, The National Map

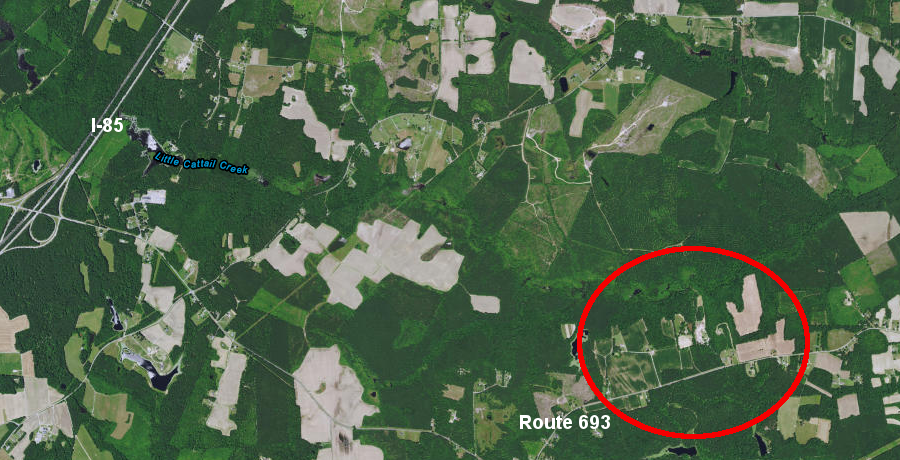

The Williamson site is southeast of Petersburg National Battlefield Park, east of I-85 in Dinwiddie County. The elevation of the site is 180 feet, and it is located near the Fall Line.

The fields on the Sally Williamson Farm from which points have been collected are located south of Little Cattail Creek. Locations with chert debitage dating back to the Paleo-Indian Period have also been identified just north of Little Cattail Creek. The creek is a tributary of the Nottoway River. The Cactus Hill site, site of pre-Clovis artifacts, is further downstream along the Nottoway River.

The Williamson site is the source of Cattail Creek Chalcedony. That distinctive form of quartz was use for making Clovis points and other tools. Based on the artifacts found by archeologists, it appears the site was occupied from 11,200-8,500 years ago (from the Paleo-Indian into the early Archaic Period). There was a wetland/vernal pool at the site then.

The high volume and type of "debitage" (waste rock, including edges chipped off cobbles) suggests the stone source was nearby, but no outcrops with evidence of quarrying have been found at the Williamson site itself. The bed of Little Cattail Creek is the Petersburg Granite, and the chalcedony may be a relic of hydrothermal metamorphism 300 million years ago.

There may have been exposed outcrops 8,500 years ago, but those were chiseled away and are now covered with soil. In addition, cobbles in the creeks may have provided some of the source material for manufacturing tools at the Williamson site.

Outcrops of chert and chalcedony have been found nearby on the Nottoway and Meherrin rivers, including at Bonifant in Powhatan County, but the Williamson site appears to have been a primary source or "base quarry." Paleo-Indians would quarry chunks of preferred rock at Williamson and walk to another site, where the chunks would be worked into tools for perhaps another seasonal round of hunting and gathering.

The Boney site in Greensville County, 30 miles away from Williamson, is a quarry reduction site where the initial chunks were processed into points, scrapers, and other tools. Some chunks were reduced only partially to create "preforms," which could be processed later into whatever tool might be required at the time before returning to the base quarry to restock.9

the Williamson Farm, between Route 693 and

Little Cattail Creek, is at the eastern edge of the Fall Zone

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

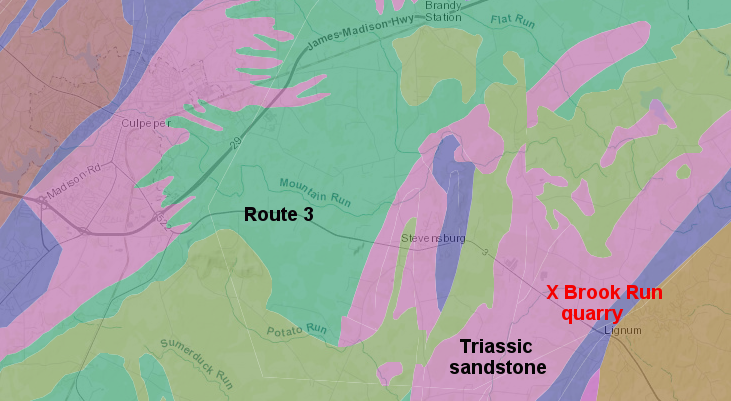

In 1998, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) identified the Brook Run archaeological site on Route 3 (ten miles east of Culpeper, about 100 yards east of the intersection with Carrico Mills road, Route 669). When VDOT routinely examined the planned route of a 4-laning of the Germanna Highway, the shovel test pits in a dense grove of cedar revealed a surprising concentration of debitage, or waste rock flakes that had been discarded, one foot below the surface. More jasper flakes, removed from a core rock in order to create projectile points, were found three feet deep.

In this case, the environmental assessment process to identify unknown cultural resources before altering the landscape worked. The previously unknown location was far away from any recognized sensitive areas (i.e., no nearby wetlands), and its discovery during the cultural resource management survey was a complete surprise.

Underneath that cedar grove was a site now designated as 44CU122. "44" stands for the state of Virginia, because the record-keeping system for cultural resources was developed in the days before 51 was assigned as the state's Federal Information Processing Standard or FIPS code. "CU" stands for Culpeper County, and "122" designates the individual site in the county.

Highway engineers and archeologists initially saw no distinctive features at Brook Run, though testing of charcoal from the site revealed that it is one of the oldest known locations of humans in Virginia.

There was no clear reason for Native Americans to carry large chunks of jasper (up to 10 pounds) to the edge of Brook Run, to manufacture tools from the chunks of raw stone there. When occupied 11,000 years ago, the site was not a high-value swampland providing food. VDOT prepared to abandon research into the mysterious flakes at site and to proceed with widening Route 3, unable to answer the key question: "why were people processing chunks of jasper into points at this location?"

Just one day before the dump trucks were scheduled to backfill the excavations and seal up the site, archeologists answered the question. They uncovered a jasper quarry at the Brook Run site, a rare resource which Paleo-Indians had identified and utilized.10

the Brook Run jasper quarry was excavated in a thin slice of distinctively-valuable rock, surrounded by Triassic sandstone

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

A natural deposit of jasper in the middle of the Culpeper Basin was a surprise. Perhaps 200 million years earlier as the supercontinent Pangea split up, quartz had been injected by hot fluids into a fault. The bedrock had cracked as the Triassic Basin formed, and multiple earthquakes created a narrow zone of fault gouge. With the help of microbes, the quartz injected into the fault zone slowly crystallized to form jasper. Continuing tectonic stresses also broke the jasper blocks into small chunks, and they were inter-mixed with other rocks that decomposed into clay.11

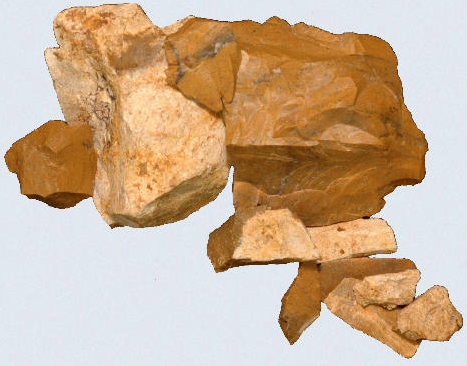

A chunk of charcoal from a spruce tree provided the date of the site. About 11,000 years ago, one or more bands of early Virginians had discovered and started to extract jasper nodules from the narrow fault zone. Spotting the reddish jasper required a sharp eye, to recognize it was different from the surrounding red sandstone of the Culpeper Basin. The softer sandstone was useless for making tools. The sandstone crumbled under pressure into loose sand grains, rather than flaked to create sharp edges.

The yellowish jasper would crack with a different pattern, creating hard flakes with edges sharp enough to cut through skin and kill an animal. Such flakes provided the knives, scrapers, spear points, and other cutting tools created by miners and stonesmiths at the site. An observer, with geological expertise passed down through the generations rather than taught in a formal classroom, spotted the narrow slice of jasper with unique value.

The Paleo-Indians selectively dug jasper nodules the size of modern bowling balls from the fault zone, leaving the clay behind. After 600 years of excavation by hand, they had created a narrow gash in the ground up to 3 feet wide and about 12 feet deep. Different foraging groups extracted that unique jasper and converted it into the high-tech tools of the time. By word of mouth, or perhaps simply by the debris from their digging, the value of that site was communicated to many generations.

chunks of Brook Run jasper

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Brook Run Jasper

To work the jasper stones free from the muddy matrix at the bottom of the vein, Native American miners squeezed into a dark hole in the ground to extract jasper from a crack just 10" wide. The prehistoric miners may have been young children, perhaps held upside-down by their ankles as they reached down into the narrow dark crevice. There was still jasper in the hole when the site was abandoned, but excavation may have become too difficult - especially when the hole was filled with water.

Only a small part of the jasper was processed into tools at the quarry; almost all was carried away to some other place. The archeologists working with VDOT found 700,000 flakes, but they were associated with creating large chunks of jasper rather than chipping those "blanks" into small individual tools needed for killing, skinning, and butchering an animal for food. Brook Run is one of the oldest mining sites in Virginia.

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, VDOT: Discovering the First Virginians

The band of Paleo-Indians took the chunks away in order to do their detail work in a safer location, where there was less risk of a competing band stealing their hard-earned raw material. That would suggest the quarry workers were not only squeezed into a tight space; they were also working in a hurry.12

archeologists found the Paleo-Indians had excavated a quarry that was 12' deep

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, VDOT: Discovering the First Virginians

Since large chunks of relatively high-value jasper were left behind, it is possible that some prehistoric conflict blocked access to the quarry site. For whatever reason, memory of its location was lost, allowing time for wind and rain to bury the quarry with another foot of sediment until the Virginia Department of Transportation's alert contractors recognized that the unusual concentration of jasper flakes was worth further study.

the Virginia Department of Transportation excavated and documented the Brook Run jasper quarry

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, VDOT: Discovering the First Virginians

Virginia's archeological sites are dated largely through the charcoal remaining from old cooking and warming fires. At Brook Run, the dates are consistently in the range of 11,000-11,5000 years before present (BP). The wood remaining in the ancient hearths is often spruce, suggesting that the climate at that time was much colder than today.

One chunk of white oak charcoal at Brook Run was about 2,000 years older, but it may be the wrong date for human occupation at the site. It could be an old remnant of an ancient forest fire that was disturbed in the mining operation, and ended up in the sediments that washed into the excavation created by the rock miners years later.13

The jasper vein and prehistoric quarry was covered by more-recent sediments until 1998, when the Virginia Department of Transportation examined the site prior to widening Route 3. The archeologists were the second group of Virginians to look closely at the site. Someone 10,000 years earlier was able to spot a small outcrop of rock, roughly 3 feet wide, that was "different." Maybe a foraging party rested there, before gathering more plant food or hunting more wild animals for dinner, and looked around. Maybe someone found a cobble of jasper in Brook Run, and explored upstream until finding the geologic fault with jasper exposed on the surface... but it is safe to assume that 11,000 years ago, the sensitivity to the geologic setting was far greater than today.

In prehistoric times, the skill of distinguishing different types of rocks was critical to survival. Bands of early hunters and gatherers were savvy about rocks. They lived in the Stone Age, a time when technology was also based on silicon dioxide (SiO2), though it was used in a form different from the silicon base of modern computer chips. Jasper, chert, flint, and other forms of quartz are cryptocrystalline forms of silicon that fracture into fragments with sharp edges, useful for crafting knives, scrapers, axes, and points for the tips of hunting spears and arrows.

In addition to using forms of quartz that originally precipitated from aqueous solutions, metamorphosed quartzite and metamorphosed volcanic rocks high in silica (metarhyolite) were chipped and cracked to form tools. Metarhyolite came from quarries in the Blue Ridge, including South Mountain in Maryland/Pennsylvania and the Uwharrie Mountain quarries in North Carolina.14

After perhaps 10,000 years of cracking and chipping rocks into desired shapes with sharp points and edges, Native Americans discovered around 4,500 years ago how to carve bowls and other shapes from a soft rock called soapstone or steatite. Stone bowls spurred a "container revolution" in technology, and may reflect a greater tendency for bands of hunters-gatherers to stay in one place ("sedentism") as wild plants were initially domesticated - and at the end of the Ice Age, after sea levels rose, estuaries rich with shellfish and anadromous fish runs became established.

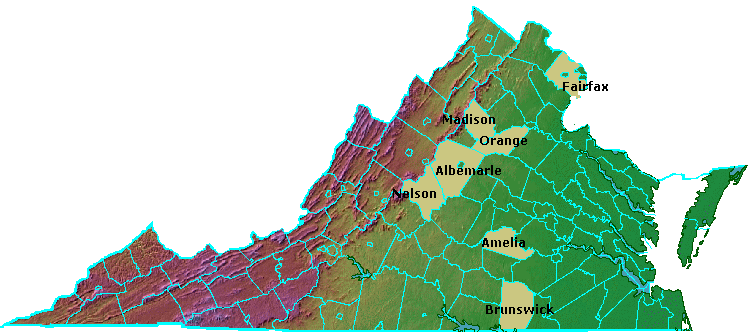

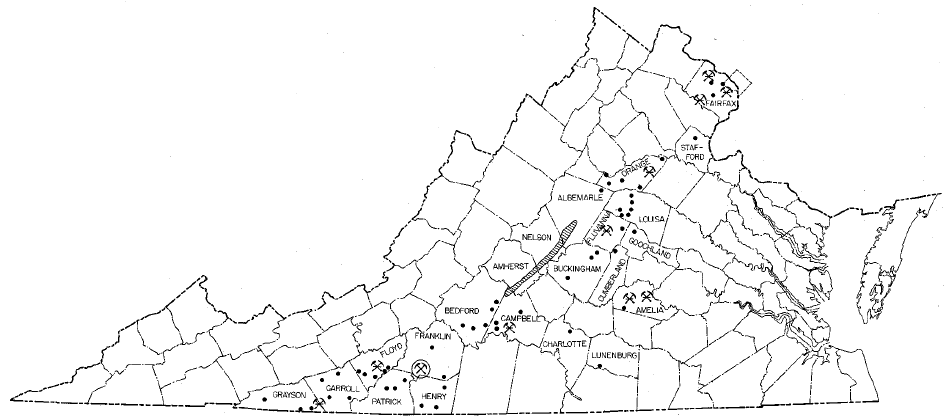

counties with soapstone quarries used by Native Americans

Source: map from Johns Hopkins University Color Landform Atlas of the United States,

county list from Encyclopedia of Virginia: Virginia Indian Ceramics

Soapstone bowls must have been heavier to carry than containers formed from skins, bark, wood, or turtle shells. In addition, soapstone was relatively rare compared to organic sources for containers; for many family groups engaged in foraging, trade for soapstone must have required different expertise than continuing traditional processes for making containers. Native Americans did not start to use soapstone bowls just to leave artifacts for future archeologists to study, so what was the advantage of switching to stone?

One possible answer: soapstone bowls were better technologically. Much of the cooking in the Archaic Period involved preparation of stews and soups, where fragments of meat/bone could be heated (along with raw fruits and vegetables) to extract nutrients. The oil from hickory nuts could be extracted more completely by heating nuts in water, and skimming off the edible oil that floated to the surface. Cooking was done by heating small stones in a fire, then dropping the hot rocks carefully into the soup/stew inside skin/bark/wood/shell containers. Stone pots were more durable for such cooking practices, resisting damage better than traditional materials.

Another possible answer: the soapstone bowls had special symbolic importance. Heavy, hard-to-acquire items may have been used for rituals rather than efficiency. Possession of a rare bowl may have identified a person/family as "elite" with higher status than other Native Americans. If so, then soapstone bowls might have been adopted because they were hard to acquire and replace, the way a Rolls-Royce car or a Picasso painting provides status today.15

Soapstone quarries are located in the Piedmont and Blue Ridge physiographic provinces. Pods of soapstone were formed as the Iapetus Ocean seafloor was shoved west and metamorphosed during the Taconic orogeny.16

Soapstone has a high percentage of talc, the main component of chalk, so Native Americans could use harder stones to carve out bowls directly from the bedrock. However, prehistoric people living in the Coastal Plain, Valley and Ridge, or Appalachian Plateau physiographic provinces had to travel to the Piedmont/Blue Ridge, or trade with groups already living there, to acquire soapstone.

location of soapstone deposits in Virginia that were utilized in historic times

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Talc, Soapstone, and Related Stone Deposits of Virginia (Figure 1)

Roughly 4,500 years ago, Native Americans along the Georgia/South Carolina coast learned how to make new "rock" in desired shapes, by heating clay in a fire to metamorphose the soft material into hard pottery. The technique of making pottery was then introduced into Virginia, either by sharing the new technology between neighboring groups or by migration of pottery-makers into Virginia.17

Clay is readily available throughout Virginia. Unlike soapstone, clay pots could be manufactured quickly as needed from local sources. The shift to pottery dramatically reduced the demand for soapstone, and may reflect a social shift to democratize access to what had been high-status items. One of the earliest forms of pottery in Virginia, the Marcey Creek ceramics, used soapstone as a temper, or addition to the clay. Temper can make clay easier to knead. Some materials used as temper allow moisture and air to escape pottery as it heats, minimizing breakage.

For thousands of years, Native Americans understood how different types of rock were suitable for tool making, and how different soils were suitable for agriculture. When the English arrived in the Woodland Period, the villages were located on floodplains where alluvial soils were relatively rich in nutrients for growing corn. When a village erred and chose less-appropriate soils, the occupants simply moved.

For example, around 1500 CE (Common Era) about 100 people settled on Wolf Creek in Bland County. The soils there are derived from Devonian shale, so productivity was low. Despite the investment in infrastructure by clearing fields, building 11 houses, and constructing a palisade, the village was abandoned after just five years.18

Wolf Creek Indian Village, occupied around 1500 CE and destroyed when I-77 was built in 1970, has been reconstructed for interpretation (Bland County)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In addition to using rocks as a material for making tools, Native Americans used rocks to make petroglyphs. For example "cupules" have been recorded in bedrock at the line of the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers. There are six remaining cupules on the Roanoke (Staunton) River in Halifax County in a meander of known as "The Cove," and further downstream where the Kerr Reservoir dam was constructed.

Cupules are round depressions carved into bedrock by using a hard hammerstone to peck away the rock and create the depression. The symbolism or utility of cupules is unclear, but they are not natural features. Whoever carved them had some intentionality, but it is unknown to us today.

Bedrock cliff faces were used as a canvas in at least two locations in Virginia. There are nearly 40 sites recorded by the Pennsylvania Archaeological Site Survey, most estimated to have been created in the last 1,000 years.19

the Salt Rock Petroglyph in West Virginia

Source: Council for West Virginia Archaeology, Recent Vandalism at Salt Rock Petroglyph and the "Prom Queen" Petroglyph

The small number recorded in Virginia may reflect not the absence of stone art but the difficulty in finding it. Only shallow scratches were pecked into the rock; massive stone sculptures were not carved by the prehistoric equivalents of Michelangelo and Rodin. If the colors smeared into those scratches were derived from plants such as bloodroot, or were animal blood, then they have oxidized and no longer stand out against the rock background.

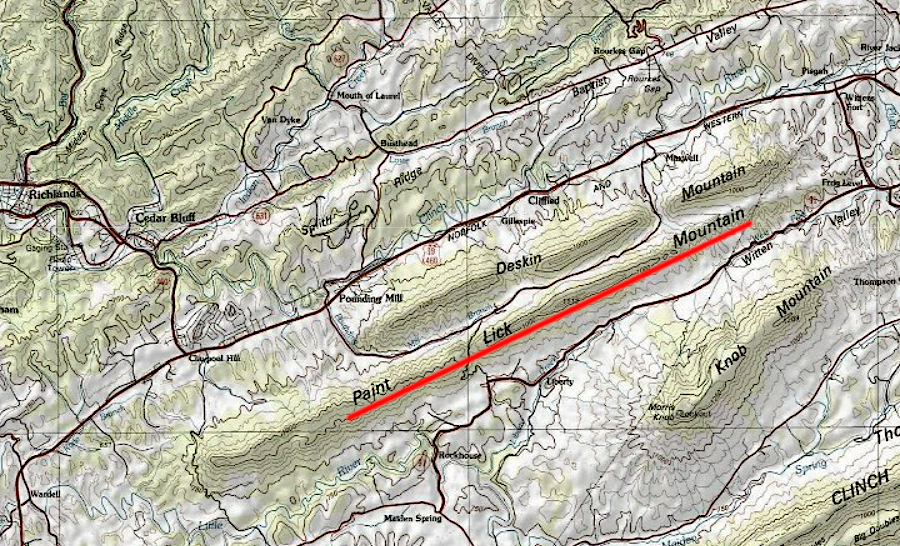

At Paint Lick Mountain in Tazewell County, there are twenty or so pictographs. Those pictographs are images painted onto the rock rather than scratched into it like petroglyphs. They were created using clay rich in hematite, reddish iron oxide, which is available at the site.

pictographs on Paint Lick Mountain are in Tazewell County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The images range from realistic representations of birds and deer to abstract designs. The artist may have used chunks of hematite to scratch red lines directly on the rock outcrop, or he/she may have crushed the iron oxide into a powder and mixed it with a binder to create a paint.

The pictographs were first documented in 1871, and have been protected by the private property owners. It is unknown who created the pictographs. It is unknown when they were created. Their meaning can only be speculated.

the pictographs on Paint Lick Mountain include both realistic and abstract designs

Source: Encyclopedia Virginia, National Native American Heritage Month and Paint Lick Mountain Pictograph (November 1, 2021)

On Little Mountain, on the other side of the Blue Ridge in Nottoway County, three glyphs resembling hands were made using a similar technique.

Further north, someone scratched glyphs into the hard metamorphic schist at Gulf Branch and the hard metamorphic quartzite at Difficult Run, both in Fairfax County. The Shenks Ferry people scratched 1,000 petroglyphs into metamorphic rocks near the mouth of the Susquehanna River starting roughly 1,000 years ago, until they were displaced by the Susquehannocks around the year 1450:20

There are two "mud glyph" caves in the headwaters of the James River. Streams naturally deposited mud on the cave walls during floods, and later stream migration left the deposits intact. Prehistoric artists used their fingers/sticks to draw chevrons, parallel lines, anthropomorphic figures, and other shapes into the mud.

The closest equivalent sort of cave artistry is in Eastern Tennessee. The art in Mud Glyph Cave was created in an area where no sunlight could reach, 800 years ago during the Mississippian culture period when Native Americans were also building large burial mounds.

The meaning of the glyphs is unknown today. Many more symbols and images of imagined creatures may have been inscribed in mud outside of caves and then washed away by high water. Sun, wind, and rain may have eroded pictographs and obscured petroglyphs that were created outdoors by different artists and shamans over thousands of years. It is also likely that hard-to-access dark zones in caves had a special spiritual significance, enhancing the power and meaning of the glyphs created there.

More sites with cave art are still being identified. Some date back to the Archaic Period; some were created in the 1800's by Cherokees just before they were forced to Oklahoma on the "Trail of Tears." The oldest cave art is estimated to have been created 6,500 years ago before people had settled into permanent encampments.

There are now 92 dark-zone cave art sites in the southeastern United States, plus other sites in Arkansas, Missouri, and Wisconsin. The dark-zone cave art includes petroglyphs and pictographs, as well as mud glyphs.

The cultural connection with the James River watershed is a mystery:21

Crumps Cave in Kentucky has mud glyphs located nearly a mile inside the cavern

Source: Kentucky Archaeological Survey video, Saving A Kentucky Time Capsule

The locations of rock overhangs and caves were probably discovered in the earliest years of human occupation, roughly 15,000 years ago, since those features could be used for shelter. Archeologists have identified 34 prehistorically occupied rock shelters along the Guest River alone in Wise County, and suggest these served as transient camps for hunting and gathering expeditions.

In far southwest Virginia, and 200 miles north in Page County, there are mortuary caves. Human remains were carried inside the caves, in some cases into the depths where it was perpetually dark. Archeologists assume the caves were viewed as a portal of some sort, perhaps into an afterlife, but the cultural significance of burial in the caves is as speculative as the interpretation of the rock art and mud glyphs.22

petroglyphs chipped out by Native Americans are displayed on a boulder at the visitor center at Great Falls Park in Fairfax County

After the Industrial Revolution, we have become disconnected from the natural sources of tools and grown dependent upon items we can buy at the hardware store. Most modern Virginians might know the difference between a Personal Digital Assistant (PDA) and a cell phone, but few modern Virginians have the geological expertise of the First Virginians.

If you walked from Colonial Beach to Harrisonburg, would you know when you were no longer walking on the Coastal Plain and had crossed the Fall Line? Would you be able to say "I'm walking on the metamorphosed sediments underlying the Piedmont" or "Hey, I'm in the sandstone of a Triassic Basin"? Would you recognize when you have crossed onto the greenstone of the Blue Ridge (near Route 29) or the limestone in the Shenandoah Valley (before you reached Route 340)?

Centuries years ago, the residents in the area would have use far different terminology to distinguish the rock formations, but the ability to distinguish different rock types would have been common. Some of the earliest Virginians spotted a tiny seam of jasper in Culpeper County, and extracted the valuable resource without having any metal tools. Who is technologically challenged - the modern resident of Virginia with fancy computers but minimal expertise in understanding the surrounding landscape, or the Stone Age residents who lived in Virginia long long ago?

|

|

|

|

|

1. Howard A. MacCord, "A Glass Arrowhead From Essex County, Virginia," Quarterly Bulletin of the Archeological Society of Virginia, March 1973, p. 162; Brian Andrews, "The three lives of a uniface," Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 54, Number 1 (February 2015), https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.11.034; Loren G. Davis et al., "Dating of a large tool assemblage at the Cooper’s Ferry site (Idaho, USA) to ~15,785 cal yr B.P. extends the age of stemmed points in the Americas," Science Advances, Volume 8, Issue 51 (December 23, 2022), https://www.doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade1248 (last checked January 16, 2023)

2. Carolyn D. Dillian, Charles A. Bello and M. Steven Shackley, "Crossing The Delaware: Documenting Super-Long Distance Obsidian Exchange In the Mid-Atlantic," Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 35 (2007), http://www.jstor.org/stable/40914512; "This Week in Pennsylvania Archeology - Paleoindian Diet," The State Museum of Pennsylvania/Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, December 9, 2011, http://twipa.blogspot.com/2011/12/paleo-indian-diet.html; "Archaeologists Have Discovered the Oldest Prehistoric Mine in America - and It Was Dedicated to Sacred Ancient Art Supplies," artnet, May 26, 2022, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/archaeologists-discovered-oldest-mine-in-america-2121451 (last checked June 2, 2022)

3. Dr. Michael B. Barber and Richard J. Guercin, "Peaks of Otter/Abbott Lake Site (44BE0259), Bedford County, Virginia: New Insight into Blue Ridge Settlement Patterning," Quarterly Bulletin of the Archeological Society of Virginia, June 2012, p.74, https://www.archeologyva.org/News/NewsQB.html; Matthew T. Boulanger, Briggs Buchanan, Michael J. O'Brien, Brian G. Redmond, Michael D. Glascock, Metin I. Eren, "Neutron activation analysis of 12,900-year-old stone artifacts confirms 450-510km Clovis tool-stone acquisition at Paleo Crossing (33ME274), northeast Ohio, U.S.A." Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 53 (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.11.005 (last checked July 7, 2022)

4. Christopher M. Stevenson, Michael D. Glascock, Robert J. Speakman, Michelle McCartney, "Expanding the Geochemical Database for Virginia Jasper Sources," Virginia Department of Historic Resources, presented in poster session for the 2007 Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/arch_DHR/resources/VirginiaJasperSources-final.pdf (last checked July 3, 2012)

5. Howard A. MacCord, Sr., James A. Livesay, Sr., "The Hertzler Site, Powhatan County, Virginia," Quarterly Bulletin, Archeological Society of Virginia, Vol. 37 No. 3 (September 1982), p. 91; "Bonnefont Jasper," Virginia Department of Historic Resources, http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/arch_DHR/Lithics/Bonnefont%20Jasper.xml (last checked October 31, 2021)

6. Gardner, William M., "An Examination of Cultural Change in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene

(circa 9200 to 6800 B.C.)," in Paleoindian Research in Virginia: A Synthesis, edited by J. Mark Wittkofski and Theodore R. Reinhart, Archaeological Society of Virginia Special Publication 19, p.26

7. Gardner, William M., "An Examination of Cultural Change in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene (circa 9200 to 6800 B.C.)," in Paleoindian Research in Virginia: A Synthesis, p.29-30, p.33

8. "National Zoological Park Comprehensive Facilities Master Plan, Front Royal Campus, Warren County, Virginia - Cultural Resources Assessment," Smithsonian Institution, September 20, 2007, p.6, http://www.si.edu/oahp/Front%20Royal%20Historic%20Preservation%20Report.pdf; Guy E. Gibbon, Kenneth M. Ames, Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia, 1998, p.278-9, http://books.google.com/books?id=_0u2y_SVnmoC (last checked July 2, 2012)

9. Phillip J. Hill, "A Re-Examination Of The Williamson Site In Dinwiddie County, Virginia: An Interpretation Of Intrasite Variation," Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 25 (1997), p.163 http://www.jstor.org/stable/40914422; "Distribution of Cherts suggesting the movements of Clovis Hunter Microbands," Stone's Archaeology Pages, http://www.angelfire.com/va/mobjackrelics/Nomenclature3.html; "The Williamson Clovis Site, 44DW1, Dinwiddie County, Virginia: An Analysis of Research Potential in Threatened Areas," Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Research Report Series No. 13, 2003, pp.8-10, http://dhr.virginia.gov/pdf_files/Archeo_Reports/DW-087_44DW001_Williamson_Clovis_Site_2003_VDHR_report.pdf; Rodney M. Peck, "The Boney Site: A Paleo Indian Site In Greensville County, Virginia," Central States Archaeological Journal, Volume 51, Number 1 (January, 2004), http://www.jstor.org/stable/43144489 (last checked August 13, 2017)

10. "Discovering the First Virginians," video produced by the Virginia Department of Transportation, 2003, https://youtu.be/fIP-BHNY-uk (last checked October 20, 2020)

11. G. William Monaghana, Daniel R. Hayes, S.I. Dworkin, Eric Voigt, "Geoarchaeology of the Brook Run site (44CU122): an Early Archaic jasper quarry in Virginia, USA," Journal of Archaeological Science Vol. 31 Issue 8 (2004), pp.1086-1087, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2004.01.003 (last checked October 20, 2020)

12. G. William Monaghana, Daniel R. Hayes, S.I. Dworkin, Eric Voigt, "Geoarchaeology of the Brook Run site (44CU122): an Early Archaic jasper quarry in Virginia, USA," Journal of Archaeological Science Vol. 31 Issue 8 (2004), p.1090, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2004.01.003 (last checked October 20, 2020)

13. G. William Monaghana, Daniel R. Hayes, S.I. Dworkin, Eric Voigt, "Geoarchaeology of the Brook Run site (44CU122): an Early Archaic jasper quarry in Virginia, USA," Journal of Archaeological Science Vol. 31 Issue 8 (2004), p.1087, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2004.01.003; "Discovering the First Virginians," video produced by the Virginia Department of Transportation, 2003, https://youtu.be/fIP-BHNY-uk (last checked October 20, 2020)

14. Vincas P. Steponaitis, Jeffrey D. Irwin, Theresa E. McReynolds, Christopher R. Moore (ed.), "Stone Quarries And Sourcing In The Carolina Slate Belt," Research Report No. 25, Research Laboratories of Archaeology - University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2006 http://rla.unc.edu/Publications/pdf/ResRep25.pdf (last checked July 2, 2012)

15. Michael J. Klein, "The Transition From Soapstone Bowls To Marcey Creek Ceramics In The Middle Atlantic Region: Vessel Technology, Ethnographic Data, And Regional Exchange," Archaeology of Eastern North America, Vol. 25 (1997), http://www.jstor.org/stable/40914421; "Early Native American Ceramics In Virginia," Virginia Department of Historic Resources, https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/Ceramics/CeramicsHistory1.html (last checked January 13, 2021)

16. Rachel J. Burks, Steven M. Lev, and Wayne Clark, "Origin Of Soapstone Within The Wissahickon Formation: Analyses Of Native American Quarries Along The Lower Patuxent River, Maryland," Geological Society of America 2006 Philadelphia Annual Meeting, Abstracts with Programs, Vol. 38, No. 7, p. 234, https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2006AM/finalprogram/abstract_111461.htm (last checked July 1, 2012)

17. "Early Woodland 1,200-500 B.C.," from First People: The Early Indians of Virginia, University Press of Virginia, http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/arch_NET/timeline/early_wood.htm (last checked July 2, 2012)

18. Dan Kegley, "Brown Johnston Site revisited: Interpreting a brief occupation of a Late Woodland village," Quarterly Bulleting, Archeological Society of Virginia, Volume 67 No.2 (June 2012), p.60

19. "Petroglyphs of Pennsylvania," Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/archaeology/native-american/petroglyphs.html; Michael B. Barber, Brian D. Bates, "Native American Cupules (Site 44ha0415) on the Staunton (Roanoke) River: Rock Art in a Riverine Landscape," Quarterly Bulletin, Archeological Society of Virginia, Volume 79 Number 3 (September 2024), https://www.archeologyva.org/News/NewsQB.html (last checked February 14, 2025)

20. Thomas Klatka, "Paint Lick Mountain Pictograph Archaeological Site," Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, May 30, 2014, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Paint_Lick_Mountain_Pictograph_Archaeological_Site; Virginia Rockart Survey, http://www.rockart-va.org/rockart1.html; "Centuries-old Susquehanna petroglyphs give history a personal touch," Chesapeake Bay Program, November 5, 2020, https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/blog/centuries_old_susquehanna_petroglyphs_give_history_a_personal_touch; Katherine M. Faull, David Minderhout, Kristal Jones, Brandn Green, "Indigenous Cultural Landscapes Study for the Captain John Smith National Historic Trail: the Lower Susquehanna Area," National Park Service, September 2015, pp.41-42, https://www.nps.gov/chba/learn/news/upload/ICL-Study-of-CAJO-NHT_-Lower-Susquehanna-Area_Final.pdf (last checked November 2, 2021)

21. Michael B. Barber, David A. Hubbard, Jr., "Overview of the Use of Caves in Virginia: A 10,500 Year History," Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, Volume 59 Number 3 (December 1997), p.135, https://caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/V59/V59N3-Barber.htm; "Ancient Art Deep in the Southeastern United States," Sapiens, October 26, 2021, https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/ancient-art-deep-in-the-southeastern-united-states/ (last checked October 31, 2021)

22. Michael B. Barber, David A. Hubbard, Jr., "Overview of the Use of Caves in Virginia: A 10,500 Year History," Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, Volume 59 Number 3 (December 1997), pp.134-135, https://caves.org/pub/journal/PDF/V59/V59N3-Barber.htm (last checked August 3, 2017)

23. Michael B. Barber, "Virginia Projectile Point Typology," The ASV, newsletter of the Archeological Society of Virginia, April 2016, http://www.archeologyva.org/Pub/Newsletter.html (last checked April 20, 2016)