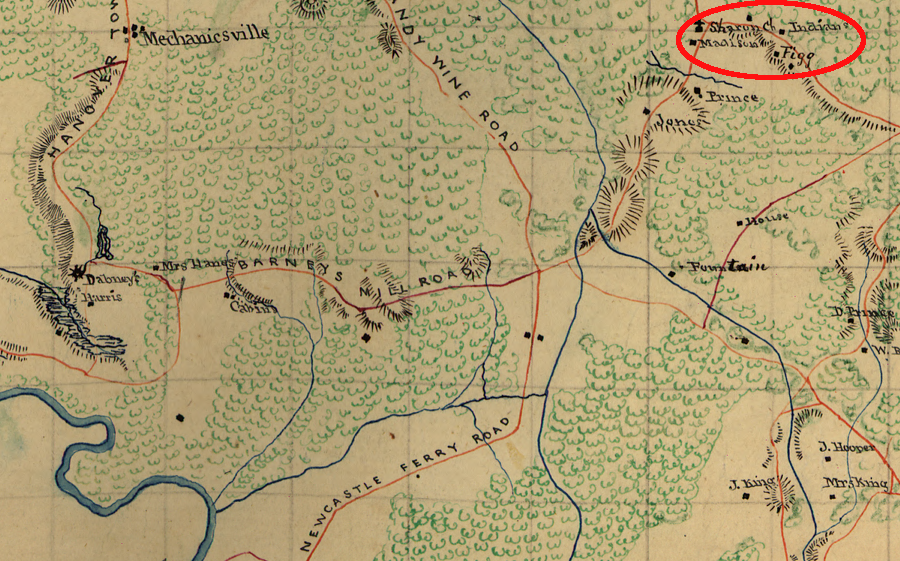

Indian View Baptist Church and adjacent Sharon School are central locations for the Upper Mattaponi today

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Indian View Baptist Church and adjacent Sharon School are central locations for the Upper Mattaponi today

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

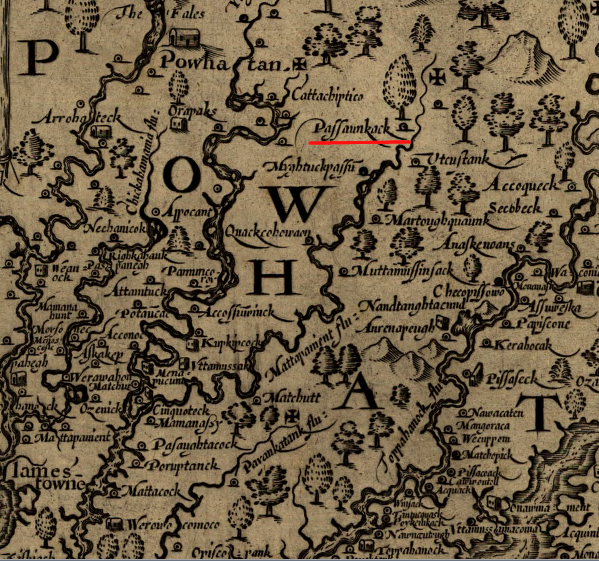

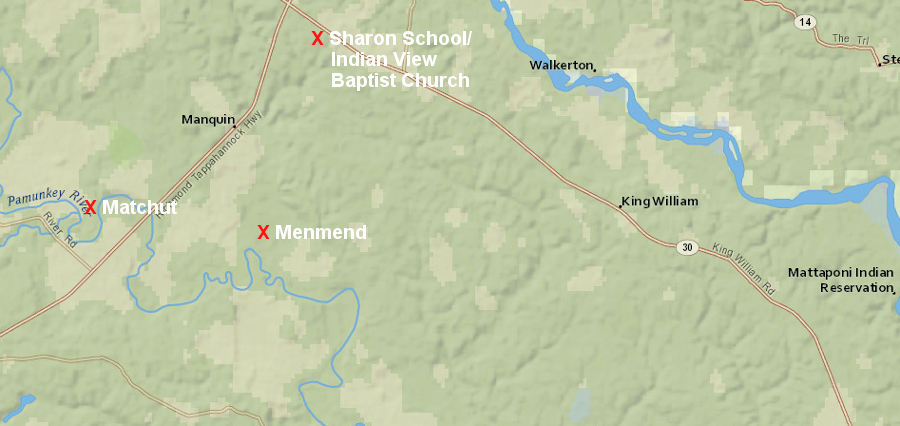

Many of the Upper Mattaponi now live in King William County, close to the Indian View Baptist Church. That site is near Passaunkack, one of the towns in Tsenacommacah and part of the paramount chiefdom under Powhatan when the English arrived in 1607.1

John Smith recorded the location of the town of Passaunkack, now the center of the Upper Mattaponi

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

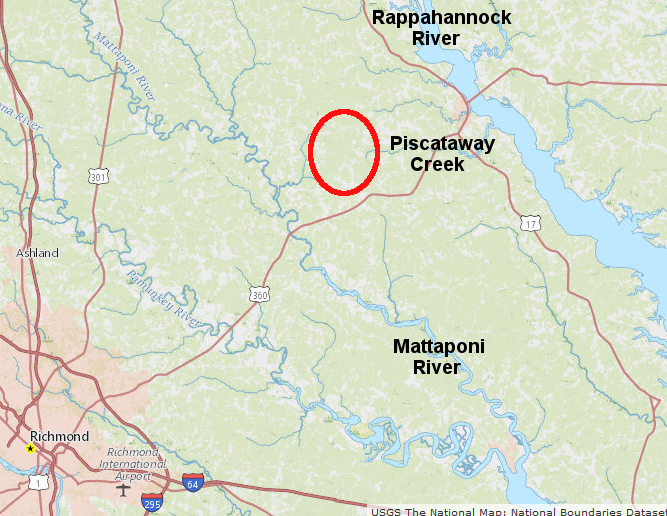

Starting in 1607, the colonists and Native Americans engaged in periods of trading, open warfare, and "cold war." To escape retaliation after Opechancanough's 1644 uprising launched the Third Anglo-Powhatan war, the Mattaponi moved to the headwaters of Piscataway Creek on what is now the boundary between Essex and King and Queen counties.

Expanding English settlement increased the pressure to relocate the Mattaponi again, to make their land available for land speculation. They moved back to the Mattaponi River in the 1660's, and may have lived together with the displaced Chickahominy. Also in the area were the Rappahannock and the Moraughtacund. A 1670 map does not identify a single tribe at the site, calling it just "Indian Land."2

the Third Anglo-Powhatan war spurred the Mattaponi to migrate away from English settlements to the watershed divide between the Rappahannock and Mattaponi rivers

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Bacon's Rebellion in 1676 further disrupted settlement patterns. In the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation, Cockacoeske asserted authority to sign for "the severall Indians under her Subjection," presumably including the Mattaponi.3

colonial pressure for land displaced tribes westward, and in 1670 several groups of Native Americans lived near the headwaters of the Mattaponi River

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670 (by Augustine Herrman, 1670)

The tribe was disrupted in 1683 by an attack from an Iroquoian-speaking group. The assault may have come the Seneca from New York, one of the other groups in the Iroquois Confederacy, of the Susquehannock. The remaining Mattaponi may have moved in with the Pamunkey where the current Pamunkey and Mattaponi reservations are located. Some may have lived with the Chickahominy, who got a 3,000-acre reservation in 1695 at Passaunkack.4

Though the Chickahominy Reservation was eliminated around 1718, Native Americans continued to live nearby. By the 1880's, the area now occupied by the Upper Mattaponi was called "Adamstown." The Upper Mattaponi believe that the name comes from an interpreter, James Adams, who translated for the Native Americans living there at the start of the 1700's. In 1921, the Adamstown band adopted the name of Upper Mattaponi Tribe.5

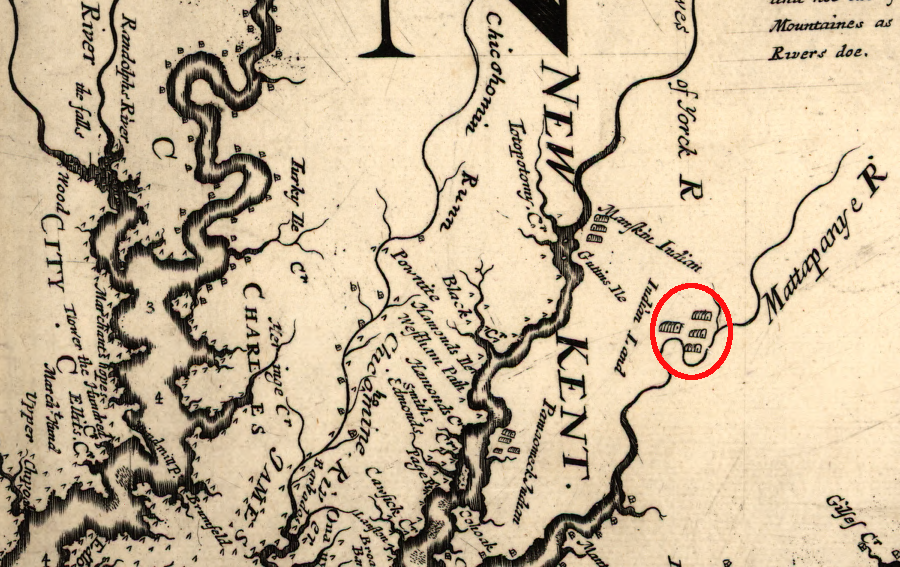

the Confederate Engineer Bureau documented the presence of Adams families in King William County

Source: Library of Congress, Map of King William County, Va (by Benjamin Lewis Blackford, c.1865)

The Upper Mattaponi, like other Native Americans in Virginia not living on a reservation, struggled to maintain their identity while avoiding hostile responses from white society. Before the Civil War, whites often failed to distinguish between Native Americans and free blacks they considered potential leaders of a slave rebellion.

After the Civil War, Native American groups continued to maintain a separate identity, not white and not black, and refused to attend segregated schools designated for blacks. As a result, a key part of Upper Mattaponi history is Sharon School. It was constructed in 1919 by what were called the Adamstown Band, after the Federal government failed to respond to an 1892 request for education funding.

The local tribal members built Sharon School, with assistance from the Mattaponi and Pamunkey tribes. Even after the Upper Mattaponi transferred the building and land to the county in 1925, Sharon School:6

the presence of "Indians" at Sharon Church was noted on Civil War maps

Source: Library of Congress, Map of King William County, Va (1863)

The first school building, a one-room wooden frame structure, opened in 1919 and survived until 1964. Enrollment ranged from 15-25 when school met in that building. An eight-room brick school with indoor plumbing was completed in 1952, as the state sought to protect separate-but-equal segregation by upgrading facilities for non-whites. The number of students increased up to 35 before that school closed.

Since the Upper Mattaponi school was not on a reservation, it received little state funding until after World War II. Until 1952, the school classes stopped after the 7th grade. Students seeking further education had to leave home for a boarding school, such as the Baptist-run Oak Hill Academy in far-away Grayson County or Bacone Junior College in Muskogee, Oklahoma.

Between 1952-1965, Sharon School offered classes only through the 11th grade. Only after integration in 1965 were the children of the Upper Mattaponi able to earn a high school diploma at a local school.

Some Rappahannock children attended as well between 1963-65.

After the King William County schools were integrated in 1965, Sharon School was closed. The county transferred ownership of the building to the tribe in the 1980's, and it serves as the Tribal Center now.7

Source: Sharon Indian School Foundation, Tribal Chat #3: First Impressions of the Building

The need for the Upper Mattaponi to define their group identity was exacerbated by other Jim Crow laws, such one passed in 1900 requiring railroads to operate separate passenger cars for "white" and "colored people." The Pamunkey pressed for clarification, and the railroads decided to allow all Native Americans to use the "white" cars.

Ethnologist James Mooney interviewed Native Americans in Virginia in the late 1800's, producing a greater awareness of tribal identity among those not living on the Pamunkey and (after 1894) Mattaponi reservations He heard second-hand that there was an Upper Mattaponi community, consisting of 40 people in the 1890's.

Ethnologist Frank Speck discovered a group of impoverished people living in log cabins with little understanding of their long heritage. With his encouragement, the group officially organized as the Upper Mattaponi tribe in 1921 and adopted the bylaws used by the Pamunkey.

The General Assembly passed the Racial Integrity Law in 1924. Dr. Walter Plecker actively sought to force local officials to classify Native Americans as "colored," assuming all had at least some ancestors who were slaves or freed slaves. The clerk of King William County ignored Plecker's directions and continued to record the Upper Mattaponi as "Indian."8

In World War II, the Upper Mattaponi were not drafted as blacks. Instead, the Selective Service designated a special "Indian Day," and those who were drafted served as white men in the still-segregated military. In 1943, after Dr. Plecker circulated a list of family surnames to county officials and advocated for them all to be classified as "colored," the Upper Mattaponi compiled an official tribal roll. The Pamunkey and Mattaponi, the two Virginia tribes with state reservations, did not assist publicly. They feared helping the non-reservation tribes would threaten their own status.

Federal officials were not protectors of the Native Americans. The US Congress passed a law granting citizenship to all Native Americans in 1924, but offered no assistance in getting them register to vote until the 948 election. In the 1940 Census, almost all enumerators complied with Dr. Plecker's racial classifications. Federal officials claimed there was no treaty between the Upper Mattaponi (or other Virginia tribes) with the Federal government, so there was no justification for Federal involvement.

The Office of Indian Affairs did provide some assistance after World War II. It notified the Pamunkey, Mattaponi, and Upper Mattaponi that students from those tribe would be allowed to attend high school at Cherokee, North Carolina. That opened the door for all Virginia tribes to send children to distant boarding schools, in order to complete high school.9

In the dispersal of the Mattaponi during the 1900's, a group settled in Philadelphia in the 1900's:10

By 1950, state officials determined there were 175 members of the Upper Mattaponi, including 70 children. The youth migrated from their impoverished area of King William County to the urban area of Richmond to find work. At some point, the tribe failed to submit the necessary paperwork to the State Corporation Commission to maintain its charter of incorporation.

After a new and more-energetic chief was elected, the charter was renewed in time for the Bicentennial events in 1976. On March 25, 1983, the Virginia General Assembly formally granted state recognition to the Upper Mattaponi and five other tribes in Joint Resolution 54, starting a process that has led to state recognition of 11 tribes by 2017.11

When the tribe decided to seek Federal recognition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs required documentation of organized existence back into the 1900's. Most of King William County's official records survived the Civil War but were destroyed in 1885 when the courthouse burned. Other state and local records associated with the Upper Mattaponi were altered during the segregation era.

There are no Federal treaty documents to use as a reference. The US Government was not created until long after the tribe had stopped participating in any form of direct warfare with English settlers.12

As a result, hopes for Federal recognition rested upon action by the legislative branch, not the executive branch of the Federal government. The Upper Mattaponi joined with the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Rappahannock, Nansemond, Monacan, Pamunkey, and Mattaponi to organize the Virginia Indian Tribal Alliance for Life in 2001, and it has pushed for Congressional approval of the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act.

The Pamunkey and Mattaponi, with the history of their reservations, chose to stay with the process managed by the Department of the Interior. The Pamunkey obtained formal recognition through that administrative process in 2016.

The Upper Mattoni and six other tribes were formally recognized by the Federal government via the legislative process two years later on January 29, 2018, after the US Congress passed the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act. The separate Mattaponi tribe, with its small reservation on the southern bank of the Mattaponi River, received state recognition in 1983 but is still not recognized formally by the Federal government.

the Upper Mattaponi have been a state-recognized tribe since 1983 and a Federally-recognized tribe since 2018

Source: Upper Mattaponi Tribe

Leadership of the modern Upper Mattaponi includes a chief, assistant chief, secretary of the treasury, and five other members of the council. Every four years, members of the tribe get to vote for their leaders. The role of the council is decisive in making decisions, and the chief represents the tribe in negotiations with various organizations and at public events. In 2009, it had an estimated 575 members.13

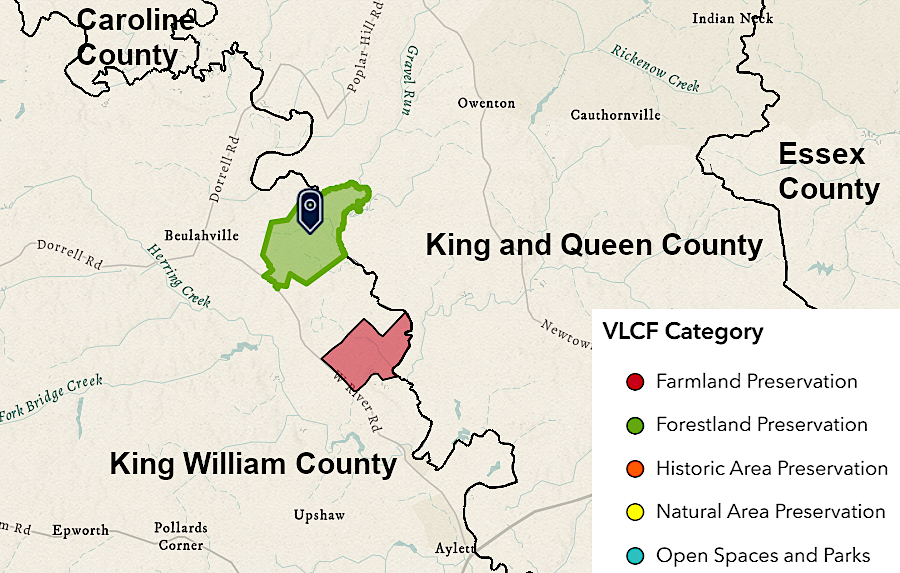

In addition to the two-acre site with Sharon School, the Upper Mattaponi purchased another 25 acres of land across the street. The Bureau of Indian Affairs in the US Department of the Interior accepted the two parcels "in trust" in 2022.14

The tribe's Return to the River initiative has been successful in expanding its land ownership further. In 2023, the Upper Mattaponi were able to acquire 853 acres of ancestral lands, including a former sand & gravel mine. The property included over two miles of frontage along the Mattaponi River and 550 acres of forestland. 90% of the funding ($3,164,923) came from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), plus a $310,000 grant from the Virginia Land Conservation Fund.

the Upper Mattaponi acquired 853 acres (green polygon) in 2023, part of the tribe's Return to the River program

Source: Virginia Land Conservation Foundation, Conserving Virginia’s Diverse Landscapes for 25 Years

The Virginia Land Conservation Foundation Board of Trustees approved its grant after clarifying how the land would be conserved in perpetuity. It was unclear how an agency of the Commonwealth of Virginia could sue in a state or Federal court to force compliance with a contract or deed restriction by a Federally-recognized tribe. In the end, a grant agreement document was:15

the Upper Mattaponi live close to Powhatan's last capital at Matchut and Opechancanough's capital at Menmend

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

![]()

Virginia has defined a geographic area where the Upper Mattaponi tribe should be consulted on state projects

Source: Secretary of the Commonwealth, 2025 Report Localities for Tribal Consultation