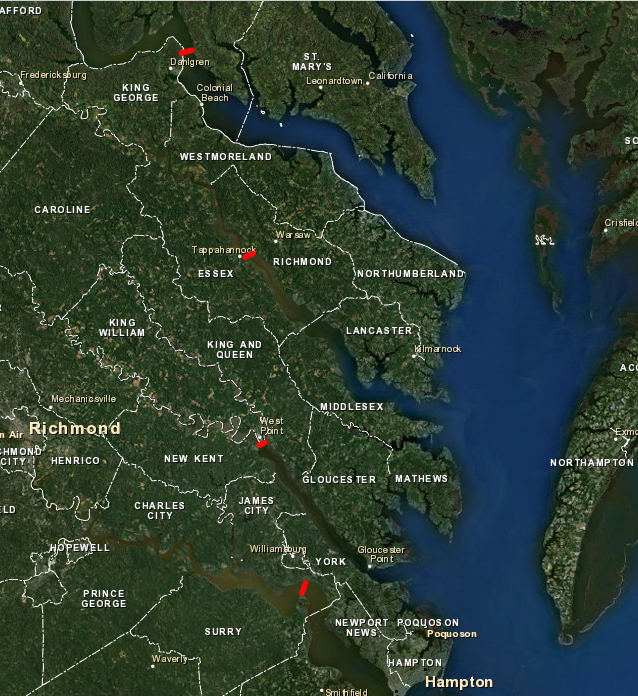

upstream salinity boundary (roughly 5ppt) for growing oysters

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS

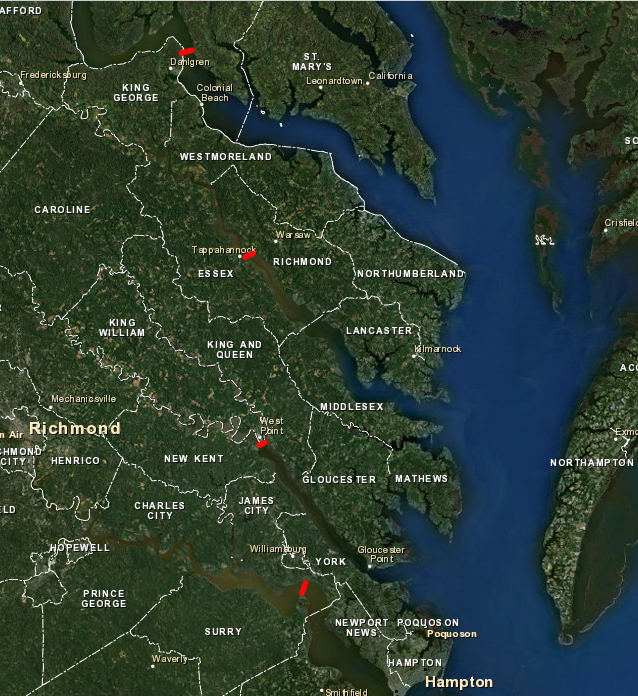

upstream salinity boundary (roughly 5ppt) for growing oysters

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS

Oysters require saltwater, with a salinity of at least 8 parts per thousand (8ppt) to grow. Different strains of oysters grow at different salinities, but salinities greater than 20ppt appear to support the greatest productivity. Oyster diseases are also salinity-dependent. Both Dermo and MSX have greater success at infecting oysters if waters have at least 10ppt salt, so the effect of those diseases was greater in Virginia's section of the Chesapeake Bay compared to Maryland's less-brackish portion.1

Oysters can not live in fresh water, though they are able to survive the substantial salinity changes common in Tidewater. At Presquile National Wildlife Refuge, salinity in the winter is low (10ppt). In later summer, when transpiration by vegetation and greater evaporation reduces rainwater runoff, salinity rises to 25ppt.2

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation cautions potential oyster gardeners:3

salinity varies between 10-25ppt annually at Presquile National Wildlife Refuge (red X), as freshwater rainfall flows into the James River

ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Oysters growing at the upstream edge of their salinity range in Tidewater rivers may die when hurricanes or other storms send a surge of freshwater downstream. In 1955, two hurricanes (Connie and Diane) flooded the Rappahannock River, causing a drop in salinity that lasted less than two weeks, but a significant percentage of oysters in the upper end of the river died over just a two-day period.4

Runoff from Hurricane Agnes in June, 1972 altered salinity in Tidewater streams for over a month. Salinities less than 5ppt in the lower 40 miles of the Potomac River killed 50% of the marketable oysters after Agnes, and blocked reproduction that year. Because saltier water is heavier, the oysters near the surface suffered low-salinity water for a longer period of time. At the end of July 1972, salinity on the surface just north of the mouth of the Potomac River was 3ppt, while in the bottom of the river channel salinity had reached 22ppt.5

However, oysters once thrived in the Potomac River upstream of the location of the modern US 301 bridge. In 2021, fisheries scientists documented about 30 historic reefs in the 10 miles upstream of the bridge. Today, the water in that stretch of the Potomac River is too fresh to support oysters. It is possible that in ancient times, before the development of agriculture and clearing of the forests in the watershed, there was less freshwater running off the surface of the land. The Potomac River may have been saltier further upstream

Another possibility is that the oysters which formed the fossil reefs came from reefs further downstream where the water was salty enough for spawning. Currents could have carried the young larvae upstream to sites where they could survive, but not reproduce.

The no-longer-productive fossil reefs might provide up to 1 million bushels of shell that could be transported to restore reefs in better habitat today. The old reefs upstream of the US 301 bridge are not coated with silt and sand, so dredging the shell for transport would have fewer impacts on water quality than other fossil reefs. However, the area is used by sturgeon for spawning. They require a hard, un-silted bottom for their eggs, so using the fossil reefs for restoration at other places could damage the sturgeon population.

Because the fossil reefs are on the bottom of the Potomac River where it is owned by Maryland, that state will make the final decision on possible reuse of the oyster shells.6

When you eat an oyster, you eat the water in which the oyster grew. Oysters are evaluated by epicures the way wines are assessed by oenophiles; the aquaculture equivalent to "terroir" for vineyards is "merroir" for oysters. One food report states clearly:7

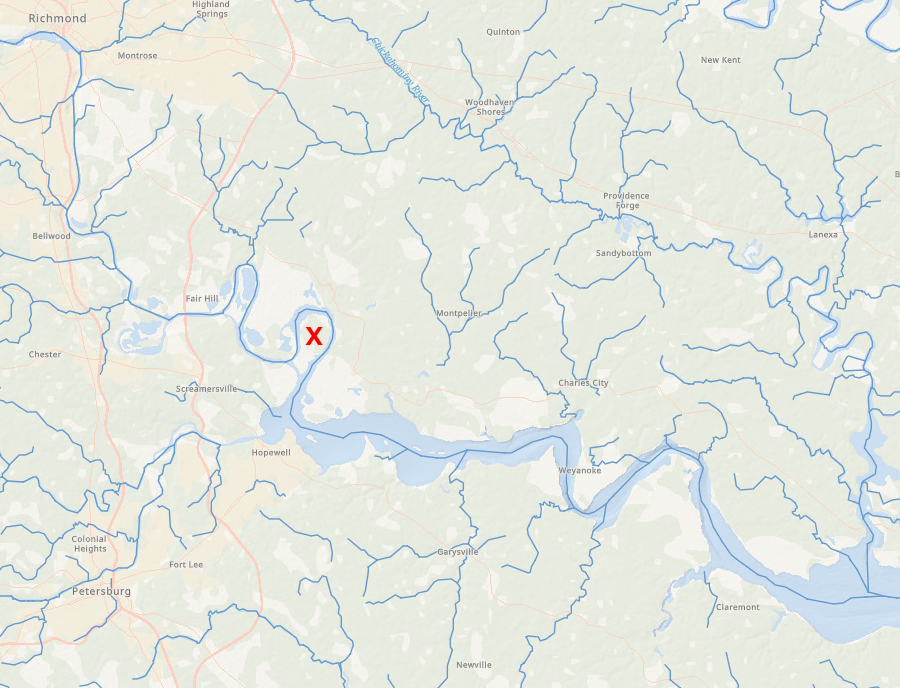

The taste of oysters is affected in particular by the salinity of the water where it grew. The Old Salt brand raised near Chincoteague Island has 28-33ppt, close to the composition of sea water (35ppt). In 2009, the Sewansecotts were marketed as "seaside" oysters, harvested from Hog Island Bay on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Eastern shore. Those oysters were 32ppt salt. In contrast, the Nassawadox Salts were marketed as "bayside" oysters, harvested from Nassawadox Creek near Bayport, with 22ppt salt. However, both Sewansecotts and Nassawadox Salts started as spat from an aquaculture operation in Willis Wharf, before being transplanted to different locations where they grew to market size.8

Nassawadox Salts grown on bayside (Nassawadox Creek), and Sewansecotts grown on seaside (Hog Island Bay), start off from a common site but develop different flavors as they grow in waters of different salinity

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS

The Rappahannock River brand is the least-salty variety grown in the Chesapeake Bay region, with just 13-17ppt. According to one guide:9

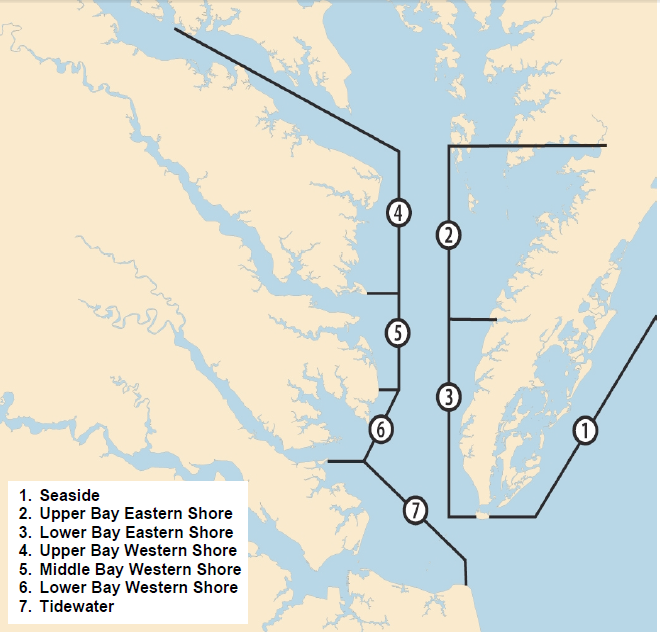

The regional flavor guide created by the Virginia Marine Products Board classifies oysters by Saltiness, Buttery/Creamy, and Sweetness. Marketing specialists have established a scale between 1-9 for the primary factor, Saltiness:10

Region | Salinity Range | Saltiness |

| #1 Seaside | 28-32 | 9 (Strong) |

| #2 Upper Bay Eastern Shore | 16-18 | 5 (Moderate) |

| #3 Lower Bay Eastern Shore | 18-22 | 7 (Very Noticeable) |

| #4 Upper Bay Western Shore | 10-17 | 5 (Moderate) |

| #5 Middle Bay Western Shore | 16-18 | 5 (Moderate) |

| #6 Lower Bay Western Shore | 16-18 | 5 (Moderate) |

| #7 Tidewater | 16-30 | 8 (Very Noticeable) |

Virginia oyster growers have define six regions based on salinity ("merroir") to facilitate marketing

Source: Virginia Marine Products Board, Virginia Aquaculture - Oyster Growers

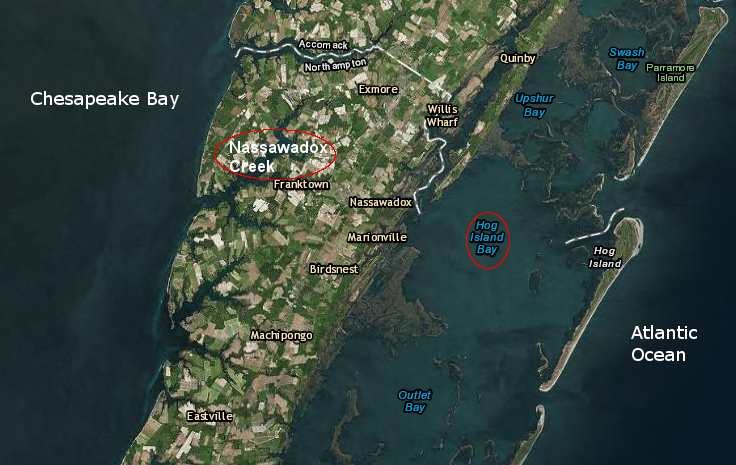

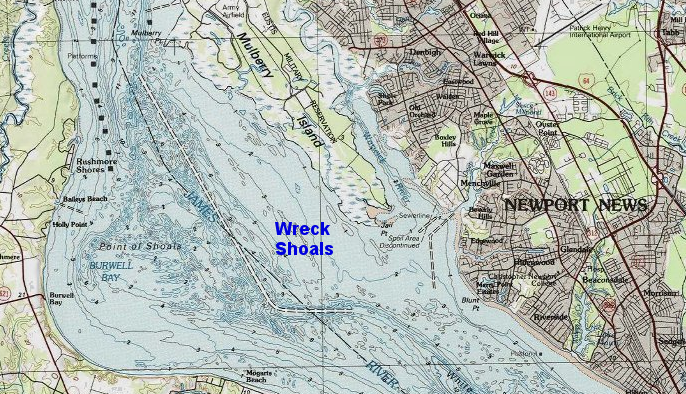

Even before modern aquaculture operations, juvenile oysters were transplanted from low-salinity areas to other locations for "grow out." Until MSX arrived in the late 1950's, the primary seedbed for Virginia was the James River between the Route 17 bridge upstream to Hog Island. The Piankatank seedbeds were developed, starting in 1963.

Wreck Shoals is still managed by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission as a seedbed for oyster harvest

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS

Those 14 miles typically had salinities below 15-18ppt in late summer, with plenty of natural shell and exposed fossil oyster beds on the bottom of the river. The low salinity limited the effect of oyster drills and diseases, allowing for successful "spatfall" followed by growth of juvenile oysters. Watermen would harvest seed oysters and deposit them to mature in other locations where natural reproduction was not successful.11

low salinity blocked predation and disease, so seedbeds in the James River supplied juvenile oysters for the rest of the state - and for Maryland

Source: "The James River Public Seed Oyster Area in Virginia," Public oyster beds of the James River seed area, as determined by the Bayler Survey, 1896

Oysters may be placed in high-salinity waters where they can gain weight quickly, before being shipped from the grow-out location to customers (comparable to how cattle are fattened with corn at feedlots before slaughter).

A connoisseur can not rely upon just the label associated with an oyster, the reputation of the supplier is important as well. An oyster touted as coming from the Atlantic Ocean side of the Eastern Shore may have been harvested there, but that oyster might have spent the previous two years growing in the Gulf of Mexico. To protect the brand identity of Virginia-harvested oysters, state law requires that "Virginia oysters" must have spent at least six months in the waters of the Commonwealth or the Potomac River.12