between 1870-1967, custom and then Virginia's segregation (Jim Crow) laws ensured white and black students attended separate schools

Source: National Archives, View of the Auditorium at Manassas Regional High School (1948)

between 1870-1967, custom and then Virginia's segregation (Jim Crow) laws ensured white and black students attended separate schools

Source: National Archives, View of the Auditorium at Manassas Regional High School (1948)

Segregation based on race became a fundamental part of the Virginia legal system in the 1600's. There were no laws in England authorizing slavery based on skin color, but the General Assembly borrowed ideas from other colonies and invented the processes needed to justify and enforce chattel slavery in Virginia.

The Civil War, followed by the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the US Constitution, disrupted the traditional system. White farmers lost access to unpaid labor. Formerly enslaved and previously-free black men and women had an opportunity to engage in economic, political, and social practices which had previously been banned.

Winslow Homer captured the altered post-war relationship, painting a formerly enslaved woman remaining seated and failing to show respect when the former mistress returned to visit

Source: Smithsonian Institution, A Visit from the Old Mistress (by Winslow Homer, 1876)

In the 30 years after the three amendments to the US Constitution and adoption of a new Virginia constitution in 1870, white Virginians succeeded in establishing a new set of laws and procedures to oppress the formerly enslaved blacks and free people of color.

The General Assembly was not required by the new 1870 state constitution or the Federal government to treat as equals the people of different races. Federal troops were withdrawn from the state as part of the negotiations to determine the winner of the 1876 presidential election Virginia's, and Supreme Court decisions created opportunities for discrimination by race so long as the language in state laws was carefully worded. Virginia's white leaders proceeded to define who was black, Indian, and white, and to establish legal segregation of the races.

The US Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to ensure blacks in Southern states had equal access to trains, ships, and other forms of public transportation. It also banned discrimination based on race in schools, public accommodations, and selection of juries. John Mercer Langston helped draft the bill, and later became the first man of color to be elected to the US House of Representatives in Virginia. (After contesting the initial results, he was seated for the last seven months of the 51st Congress.)1

However, the Federal government did not enforce the act, in part because of concerns regarding its constitutionality despite a positive ruling in 1875 by the U. S. District Court for the Western District of Virginia. Black men sought to enter bars and a barber shop in Richmond after passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and there was no response by government officials when the men were forced to leave.

In 1883, the US Supreme Court ruled that the law was unconstitutional; the Federal government could not outlaw racial discrimination by individuals or businesses. Actions by state governments could be affected by the 14th Amendment, but not actions within the private sector. Under the 13th Amendment, individuals could file civil cases but discrimination based on race was - in the eyes of the US Supreme Court - not a relic of slavery.2

Source: UVA Engagement, Ghosts of Segregation – Book Discussion

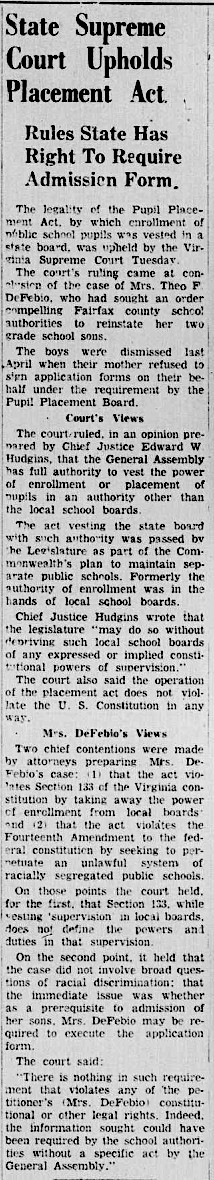

the newspaper in Prince Edward County reported on a court decision upholding the Pupil Placement Act

Source: Library of Congress, The Farmville Herald (December 6, 1957)

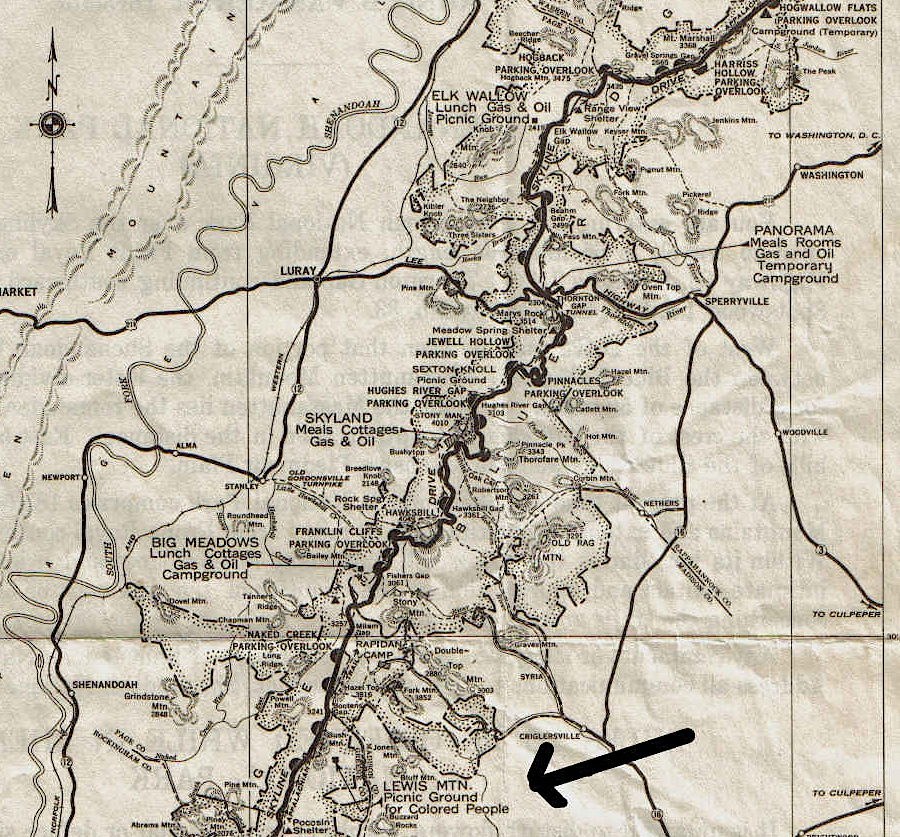

until 1950, Shenandoah National Park was segregated and "colored people" were directed to Lewis Mountain campground

Source: National Park Service, When Lewis Mountain was segregated, Shenandoah National Park, 1939 and Guide Map of the Shenandoah NP, 1938

during Jim Crow, bus service was prioritized for students attending the white-only schools

Source: Library of Congress, Negro children coming home from school. Halifax County, Virginia (by Marion Post Wolcott, September 1939)

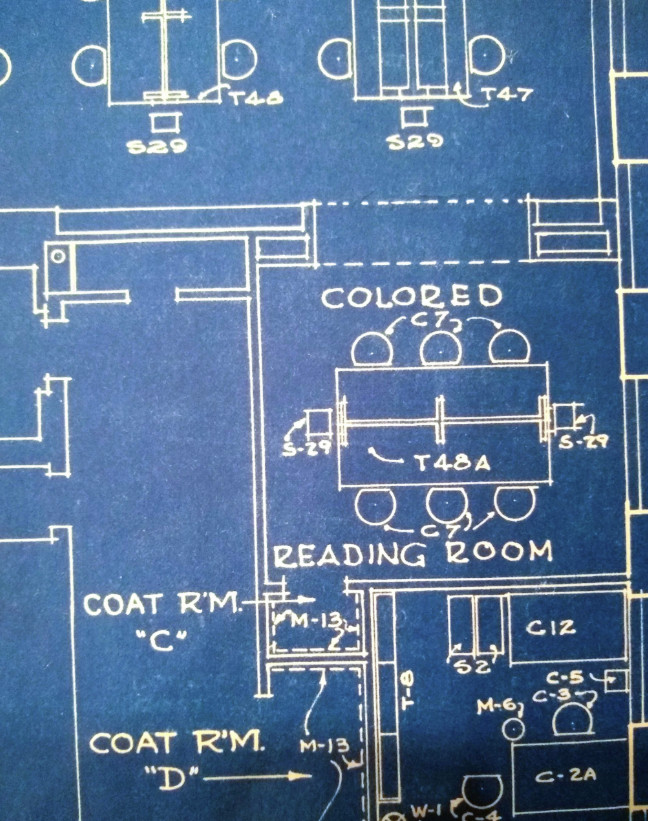

the Library of Virginia designated a separate reading room for "colored" patrons

Source: Library of Virginia, Service & Segregation: A Look Back

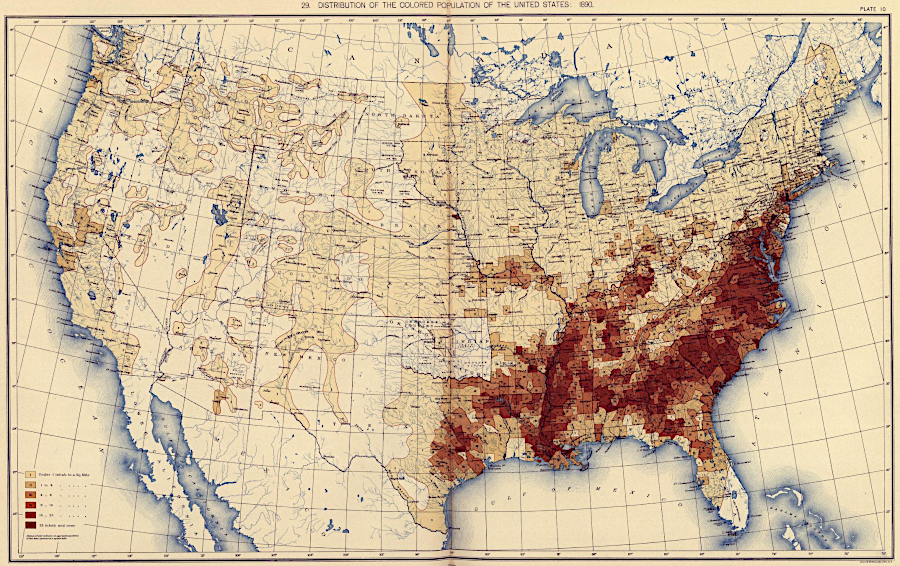

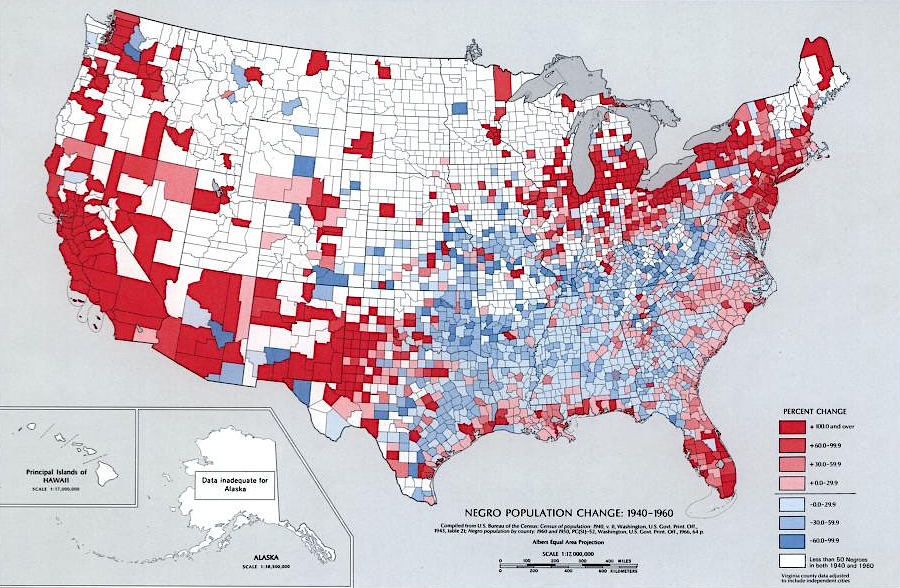

to escape the social and economic impacts of Jim Crow segregation, black residents in the Deep South began a mass migration to northern states and urban areas

Source: Library of Congress, Statistical atlas of the United States, based upon the results of the eleventh census (1890) and The national atlas of the United States of America

Maggie Walker was president of the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, with offices at the southeast corner of First and Marshall Streets in Richmond

Source: National Park Service, St. Luke Penny Savings Bank entrance with staff

the National Park Service now manages the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site

Source: National Park Service, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, Virginia

Virginia laws required segregated programs for Boys State civic training sessions

Source: Library of Virginia, American Legion, Boys' State (June 23, 1960)