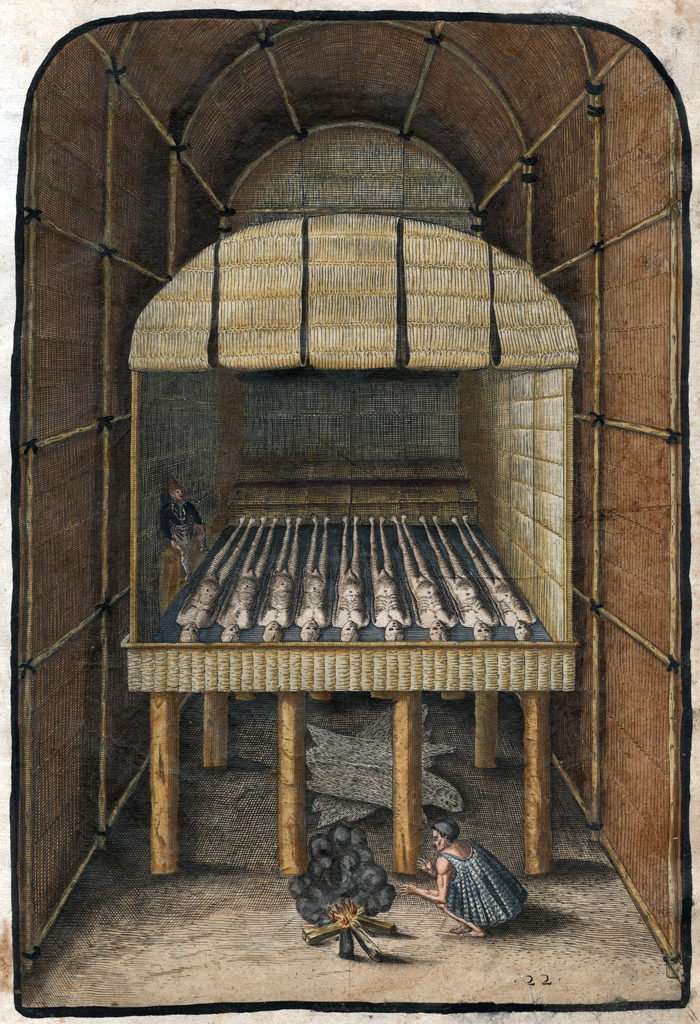

Algonquian tribes on the Coastal Plain buried the bones of chiefs in temples

Source: LearnNC, Peoples of the Coastal Plain

Algonquian tribes on the Coastal Plain buried the bones of chiefs in temples

Source: LearnNC, Peoples of the Coastal Plain

Modern graveyards are seen as sacred spaces and eternal resting places, but the Native American dead in Virginia have not been allowed to rest in peace. With a few exceptions, their graves are unknown and unprotected from modern disturbance.

Looters seeking artifacts and amateur archeologists have scattered bones as they excavated burials. Professional archeologists have, in the past, removed skeletons and grave goods for study. The remains have been stockpiled in museums and storage vaults of government agencies. In many places across Virginia, there is little more than local lore that graves were found at a location. For example, the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority (now NOVA Parks) once published a brochure about "Prehistoric Indians" at Potomac Overlook Regional Park that noted at the Donaldson archeologic site (44AR3):1

Finding Native American graves is not easy. Prior to modern times, no Native American graves were permanently marked using granite headstones inscribed with names and dates of birth and death. Grave markers, if any were placed, have rotted or blended into the natural landscape.

All Native American cultures were disrupted and displaced from their traditional lands through the Contact Period. Memories of sacred locations were lost, or suppressed to limit intentional disturbance by colonial settlers. A few burial temples and mounds were identified by early colonists and later settlers, and nearly all were destroyed.

Calculating the number of Native American graves in Virginia requires some speculative math.

Population statistics for Native Americans since the initial occupation of Virginia are conjectural, but people have been living and dying in Virginia for perhaps 15,000-20,000 years. Adoption of agriculture 3,000 years ago increased the food supply and led to the last surge in population. The largest number of people in Virginia before arrival of the Europeans may have been after 1200CE (Common Era), after corn became the primary agricultural crop.

When the English arrived at Jamestown, there may have been 15,000 people in Tsenacomoco, the territory controlled by Powhatan. A total of 50,000 people may have been living in all of what is now Virginia, including Tsenacomoco.2

If average life expectancy (including child mortality) was 25 years, then approximately 1,000-3,000 people died each year for 300-500 years after the commitment to corn. That death rate, plus all the deaths during the Paleo-Indian, Archaic, and Early/Middle Woodland periods, could result in over 1,000,000 Native American gravesites in Virginia.

Where are the 1,000,000 Native American graves?

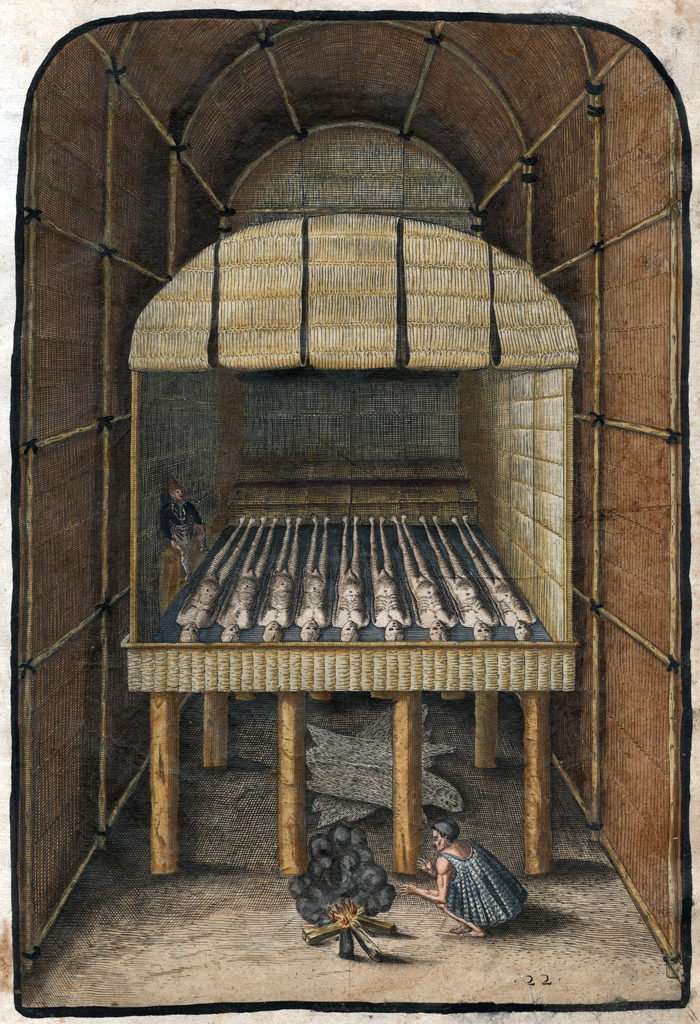

Indian Grave Ridge records where burial mounds were found in the Shenandoah Valley

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Rileyville, VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle

Customs for burying the dead changed over time, but human societies traditionally have placed the bones of most of the dead into the ground with some sort of ritual process. It is unlikely that the constantly-migrating hunting bands in the Paleo-Indian and Archaic periods carried a corpse far from wherever a person died. Burial sites must be scattered across the state, on whatever ridges and in whatever valleys where someone died.

It is theoretically possible that dead bodies were not buried, but left at the spot or cast into the woods/rivers. That is most likely for those killed during warfare and raids, where the losing side had no opportunity to recover their dead and bodies were left to decay on the surface of the ground. Even without a burial ceremony, the sites of battles where family members died would have been significant in ancient times. The final resting places for those bodies would have significance in modern times too, if we knew those locations.

The number of known Native American burial sites is only a tiny percentage the total burials that occurred prior to the arrival of Europeans. All graves of those who died in the Paleo-Indian period, the original Virginians, are lost to history. We have found stone artifacts and small pieces of charcoal from Paleo-Indian fires in Virginia, but no bones of Paleo-Indians. In all of North America, only one grave associated with Clovis artifacts has been discovered.3

There are a few grave sites in Virginia that may date back to the Archaic Period. Since colonization started in 1607, cultural disruption of historic tribes has been equally effective in erasing knowledge of where more-recent Woodland Period gravesites are located.

With three major exceptions - burial mounds, stone cairns, and mortuary caves - a Native American burial in Virginia will not be obvious to the casual observer. A surveyor marking parcel boundaries, a bulldozer operator excavating flat spaces for construction, or a football team playing on a school's ballfield will not be aware that someone may have been buried at that location sometime over the last 18,000 years.

Even less obvious will be sites with cremated remains. In Georgia, archeologists have discovered a site with seven cremated individuals who were buried more than 3,500 years ago. The practice of cremation may have been brought from the Great Lakes region, together with copper that was found with the cremains.4

Decay of human bodies in acidic soils over time has removed most physical evidence. Unique prestige goods made of long-lasting stone might have been be buried with spiritual, military, and political leaders, but hunting and gathering societies traveled light.

All crystals, spearpoints, and other items had to be carried between campsites. Hunters and gatherers in the Paleo-Indian and Archaic periods carried few prestige goods that might be placed in a grave. Within the ground, bones and organic artifacts, such as leather/fiber bags containing pearls, shells, feathers and wooden talismans, have decayed away in naturally-acidic soils.

The worldly goods of the living were limited. Even after the development of agriculture in the Woodland Period and the arrival of Europeans, Native Americans had no closets in their houses. The amount of "stuff" in Native American society was far less than is common today; there were no racks of shoes and handbags for different types of events, and no garages filled with clutter.

There were no fancy caskets either. The body or bones of a well-respected person might be wrapped in a deerskin, bear robe, or reed mat, but it appears that was not done for the common people. Graves for all who died must have been pretty simple.

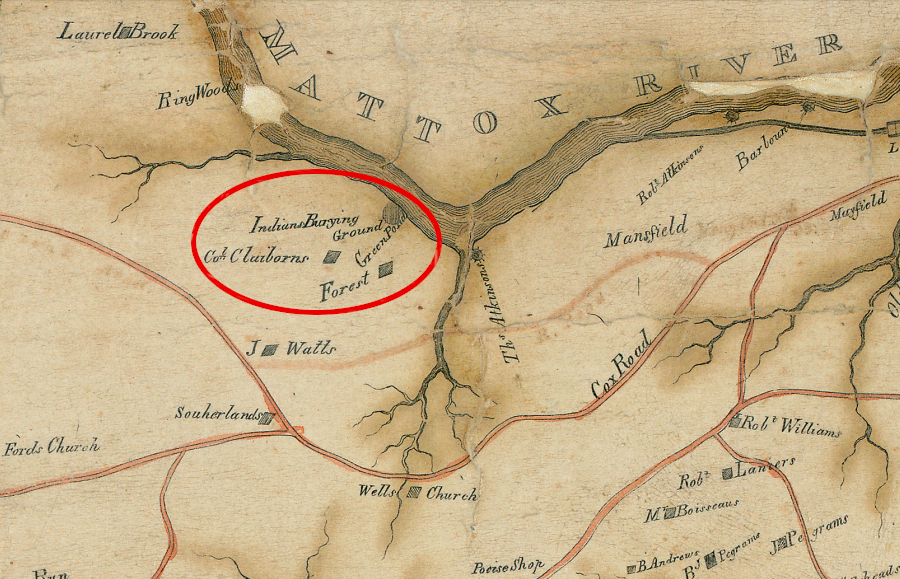

In an "egalitarian" society, grave goods and mortuary practices would be would common for all. In a "ranked" society, with social stratification distinguishing elites from commoners, burials of the chiefs and priests may be distinctly different from everyone else. In the Paleo-Indian Period, the common struggle for survival may have minimized differences between leaders and followers within families, microbands, and even larger macroband gatherings. In the Archaic Period, ranked societies may have formed and burial practices may have reflected the status of the person when they died.

archeologists and anthropologists look for distinctions in burials to determine if prehistoric societies were egalitarian or stratified with separate social classes

Source: Texas Beyond History, Life and Death at Mitchell Ridge

Knowledge of the location of the graves of nearly all Paleo-Indian and Archaic leaders, and of the hunters and gatherers they led, has been lost over time. The simple gravesites of hunters and gatherers do not stand out as distinctive, obvious features in the landscape.

Since the start of the Woodland Period around 3,000 years ago, people clustered together in towns for at least part of the year. Corn-intensive agriculture since 1200CE led to larger settlements, with longer periods of occupation. As those towns developed 800 years ago, the places where people lived were more concentrated. Similarly, the places where people died were more concentrated.

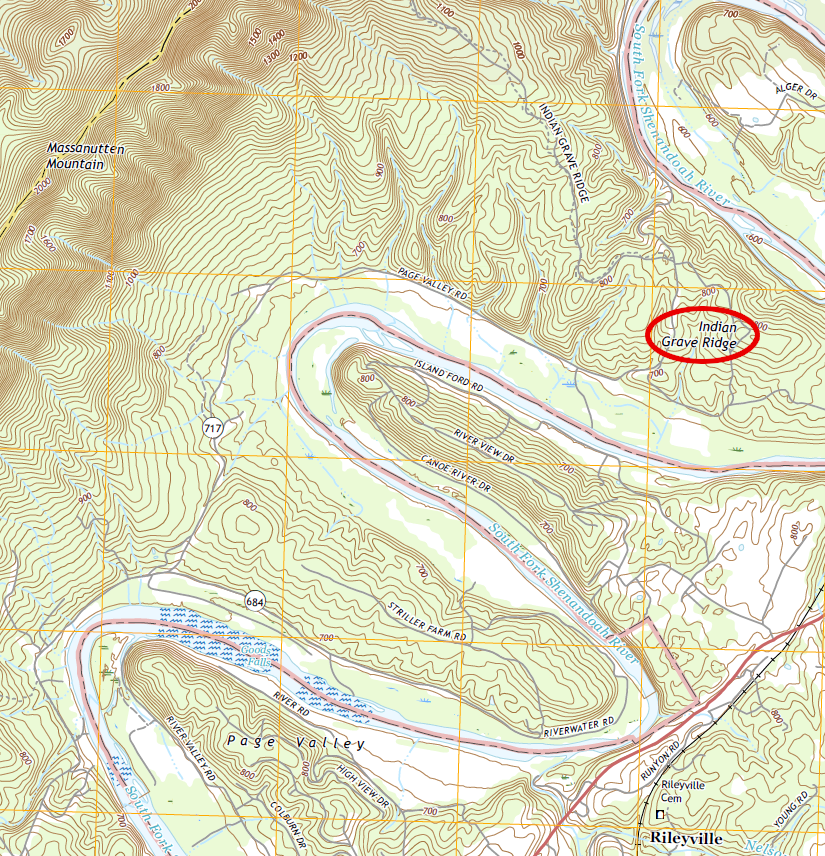

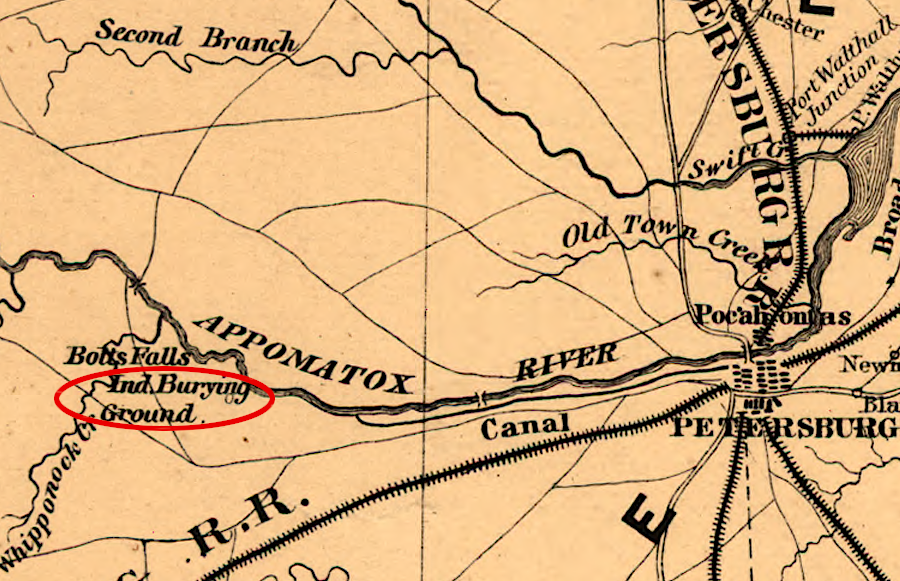

What is now called Rohoic Creek, a tributary of the Appomattox River in Dinwiddie County, was known in 1820 as Indian Town Creek. What was mapped as "Indian Burying Ground" is now archeological site 44Dw20.

knowledge of Native American burying grounds survived into the 1800's in Dinwiddie County

Source: Library of Virginia, A correct map of Dinwiddie County (by Isham E. Hargrave, 1820)

a Native American burying ground was mapped along the Appomattox River

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia (by Lewis Von Buchholtz, L. V., Herman Böÿe, 1859)

Though we do not have a complete understanding of pre-historic practices associated with death, it is reasonable to assume that those who died during that time of the year would have been buried nearby. There should be more graves near prehistoric Native American towns. Burial mounds, the prehistoric equivalent of modern cemeteries, have been identified from the southwestern edge of Virginia to the Shenandoah Valley and even east of the Blue Ridge.

During the Middle Woodland period, the dead in the northern Shenandoah Valley were buried near a town's palisade, then the bones were collected every five years or so and reburied at a sacred burial mound. Around 1250 CE (Common Era), a new culture brought new burial patterns. Unlike the preceding Albemarle Culture which used burial mounds, the people of the Page Culture buried their dead individially near their houses.5

Soil chemistry varies, so teeth and some bones may have survived for centuries. Construction of any new road, house, or other modern development near a pre-historic town could disturb burial sites, and might destroy the small remnants of skeletons as well as ceramic sherds, stone points, and postmolds still in the ground.

It was rare for archeologists to search in advance for such graves until the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the 1979 Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) required Federally-funded projects to assess potential impacts on archeological resources. Some graves were spotted in occasional "salvage archeology" projects, but protection of Native American gravesites was not a fundamental consideration before ground was disturbed for modern construction.

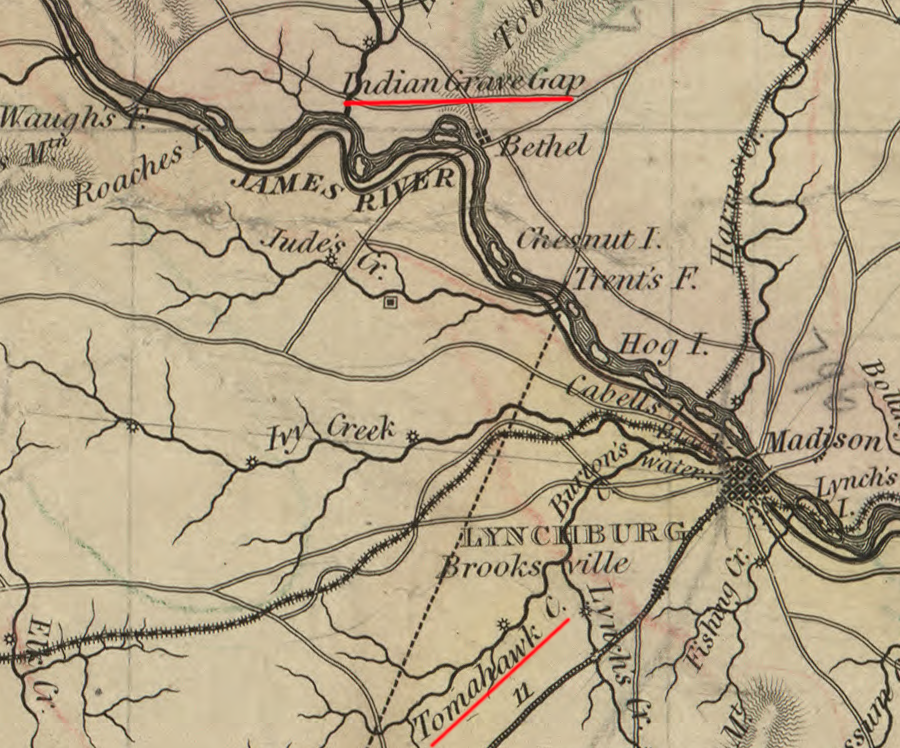

place names acknowledge the first people who lived and died near what later immigrants called the James River

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia (by Lewis Von Buchholtz, L. V., Herman Böÿe, Benjamin Tanner, 1859)

Once government agencies developed Cultural Resources Management programs, impacts on the buried remains of pre-historic sites were finally assessed on publicly-funded projects before construction destroyed any remaining evidence. Archeological studies for privately-funded projects remain rare, but on occasion city/county officials may require an archeological assessment as a condition of rezoning a parcel of land.

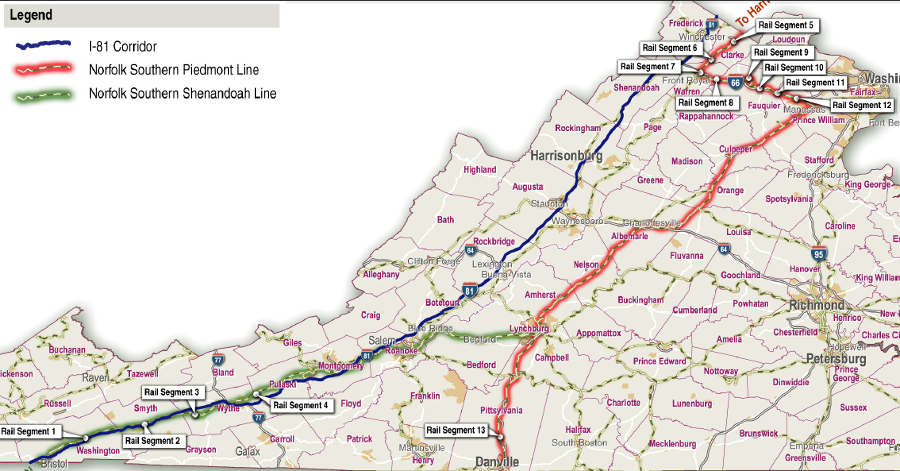

a proposal to widen I-81 triggered an assessment of archeological resources on the Norfolk Southern rail line far to the east

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, "I-81 Corridor Improvement Study," Historic Properties Technical Report (Figure 1-1)

On the Coastal Plain, the bones of elite werowances and priests (and perhaps commoners) were collected after flesh decayed and then buried in ossuary mounds. At the time English colonists came to Virginia, it was common in England to excavate bones from graveyards and place them into charnel houses, creating space for new burials.

Virginia ossuaries were sacred sites. The bones remained in the structures until they collapsed from natural decay.

John Smith visited one site with such secondary burials, the home of the Patawomeck, in 1608. Early archeological investigations there, prior to World War II, identified five ossuaries.6

John Smith saw traditional burial practices and ossuaries at Indian Point in 1608

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Smith reported that after death of a "king," the internal organs were removed and the body placed on elevated rails (hurdles). After the flesh rotted away or was removed by birds, the skeleton was collected, wrapped in a reed mat, and preserved in a temple with carvings to the sacred spirits (Okee):7

One key burial site was Powhatan's primary temple site, Uttamusack, in what today is King William County. The three, 60-foot long temples were destroyed in the Anglo-Powhatan wars, but the location still has meaning. Dominion Energy agreed to purchase the site in 2017 and donate Uttamusack to the Pamunkey tribe, as part of the mitigation required to get Federal approval to construct new high-voltage transmission lines across the James River at Skiffes Creek.8

The bodies of commoners may have been included in some ossuaries, but John Smith reports they were treated differently:9

Many Native American burial sites were looted in raids by the first English colonists at Jamestown. Modern archeologists have identified a few burial sites, but nearly all places where Native Americans were buried have been covered over with farms, roads, and houses. There may be undisturbed grave sites underwater, covered as sea level has risen further after the Paleo-Indians first arrived.

In Florida, an 8,000 year old site has been found where the water in the Gulf of Mexico is now 21 feet deep. The Manasota Key Offshore site, the first offshore burial discovered in North or South America, was a freshwater pond nine feet above sea level when first used for burials. That "mortuary pond" had been used for 1,000 years.

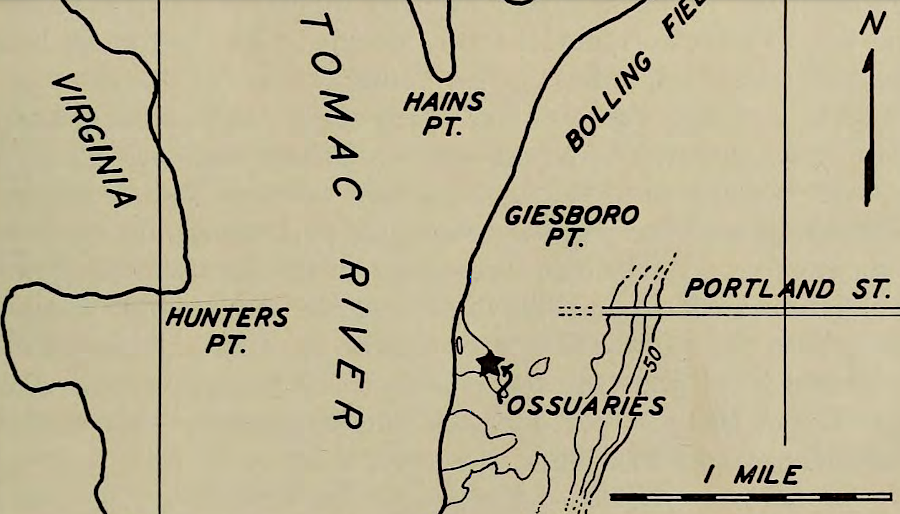

In what today is the District of Columbia, John Smith visited the town of Nacotchtanke (Anacostia) in 1608. In 1936, bulldozer operators expanding Bolling Field found evidence of the long occupation at the mouth of the Anacostia River. Two ossuaries were uncovered, where bones of bodies which had decomposed elsewhere were placed in a secondary burial.10

remains in two ossuaries, where bones had been placed for secondary burial, were discovered in 1936 when Bolling Field was expanded

Source: Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, The finding of two ossuaries on the site of the Indian village of Nacotchtanke (Anacostia) (1937)

A major road in Henrico County carries the name "Quioccasin," thought to be the term used to designate a temple or meeting place. In 2016 the Henrico County school board renamed "Harry F. Byrd Middle School" to "Quioccasin Middle School." Renaming the school after a Native American term had a special significance because Byrd had been a strong supporter of segregation between whites and other races, but no quioccasins have been preserved in Virginia.11

It is possible any house within any subdivision in Tidewater may have been constructed on top of a site where Native Americans were buried, but the residents will be unaware of that heritage. In at least two locations, however, housing projects led to discovery, excavation, and reburial of Native American graves.

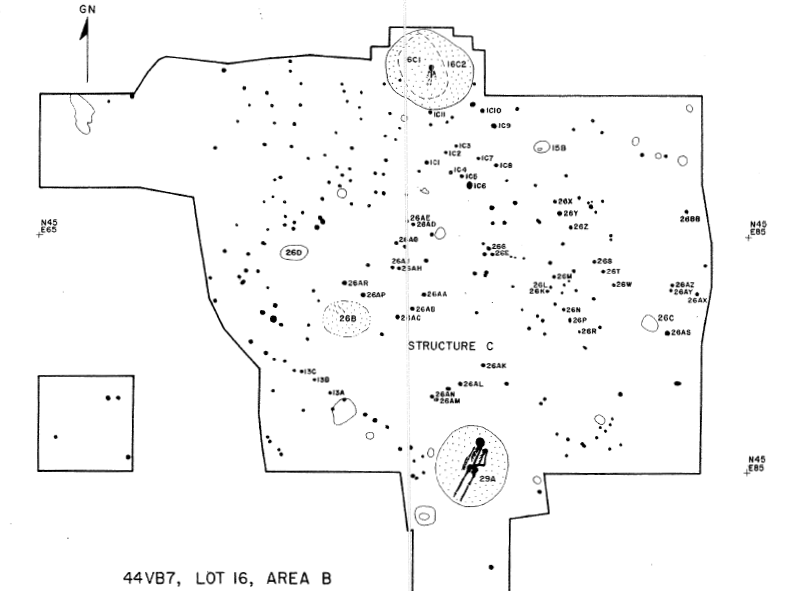

Native American burials were identified through excavations at Great Neck

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Native American Settlement at Great Neck (Figure 16)

Passage of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) added a new layer of protection for Native American burials. Federal agencies now must to consult with Native Americans before initiating projects that might disturb archeological sites.

Federal agencies and museums also had to inventory human remains obtained from federal or tribal land, determine if a cultural affiliation could be identified with an existing tribe recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and offer to repatriate items. By 2016, remains of over 57,000 individuals had been identified in museums and Federal collections.12

Around the time of the passage of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, a real estate developer near Williamsburg transformed the site of the main town of the Paspahegh into The Governor's Land at Two Rivers. The developer hired the James River Institute for Archaeology to research the site from 1988 to 1991. At times, archeologists worked just ahead of the construction equipment as they documented postholes and excavated artifacts. Graves were discovered, and 18 Native American remains with associated artifacts were reburied next to the golf course in 1993.13

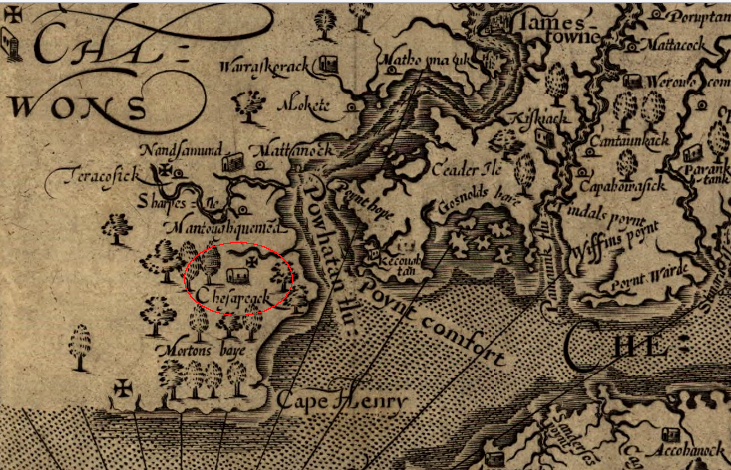

In the 1970's-1980's, graves from the Chesapeake tribe were excavated as houses were built on Great Neck on Pungo Ridge, west of Broad Bay in Virginia Beach. The burials may have marked the location of the town of Chesepiooc, center of the Chesapeake tribe.

John Smith documented the Chesapeake tribe's presence in what today is Virginia Beach

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (by John Smith, 1624)

Powhatan exterminated the Chesapeake tribe about the time when the English arrived, based on a prophecy regarding threats of enemies in the east. The remains discovered during construction of the houses could have been from the "original" Chesapeakes destroyed by Powhatan. It is possible that some burials might be from the people Powhatan sent to occupy the region.

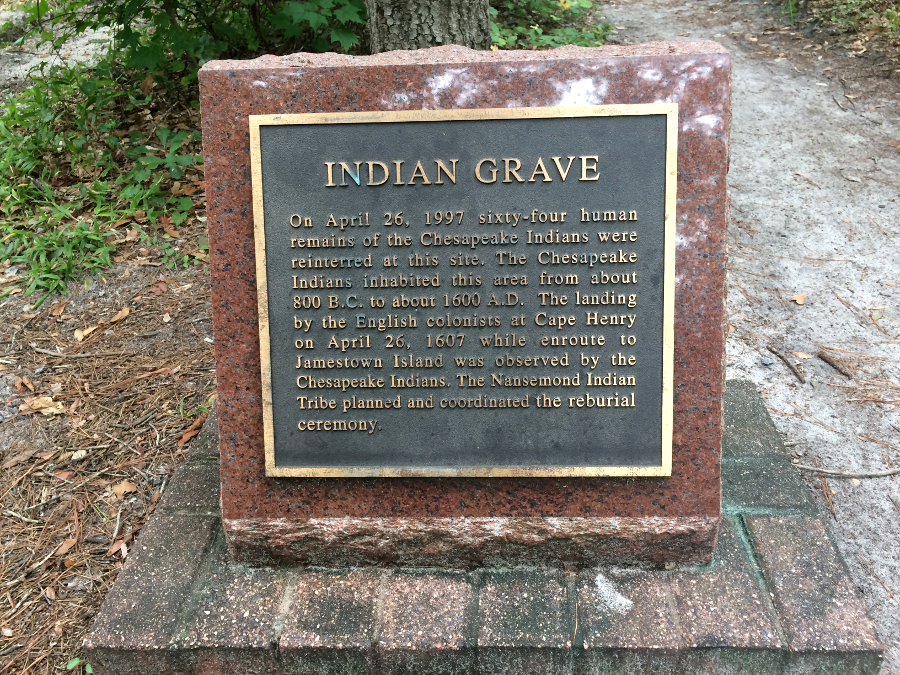

No modern version of the Chesapeake Tribe exists. The Chesapeake tribe was disrupted by colonization and the first two Anglo-Powhatan wars, and they abandoned the area before 1635. In 1997, the Nansemond tribe arranged for the Virginia Department of Historic Resources to rebury the remains of 64 Native Americans at First Landing State Park.14

When the National Park Service published a Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act report of the remains, it noted:15

64 members of the Chesapeake tribe were reburied at First Landing State Park in 1997

The chief of the Chickahominy Indians Eastern Division estimated that there were bones of 2,000 Native Americans from Virginia in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution. He proposed creating a memorial park for re-interring them, and future burials that were discovered and excavated. There would have been no distinction between tribes in the proposed memorial. The idea for a pan-tribal memorial site never moved past the idea stage. Under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, remains will be delivered to the tribe with the closest cultural affiliation.16

Until 2016, no tribe in Virginia was officially recognized, but Federal agencies may choose to consult with non-recognized groups. Researchers at Werowocomoco have been careful to invite all Virginia tribes to engage in the planning for archeological studies and future opening as a unit of the National Park Service, to invite representatives from Native American communities to visit the site, and to provide updates regarding activities and discoveries.

The Pamunkey, Chickahominy, Mattaponi, Nansemond, Rappahannock, and Upper Mattaponi formed the Virginia Indian Advisory Board for guiding activities at Werowocomoco. The board adopted a fundamental policy regarding excavations:17

the Virginia Indian Advisory Board will shape what happens next, if Native American burials are uncovered at Werowocomoco

Source: Werowocomoco Research Project, Werowocomoco: A Powhatan Place of Power

Federal agencies also invite recognized tribes from outside the state boundaries to be consulting parties, using the Section 106 process of the National Historic Preservation Act to reach consensus on appropriate actions and mitigation. In 2017, when the US Army Corps of Engineers considered issuing a "dredge and fill" permit under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act for The Meadows shopping center at Abingdon, it invited all three recognized Cherokee tribes - the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians based in North Carolina, plus the Cherokee Nation and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians based in Oklahoma.18

Known pre-historic Native American graves sites are limited to archeological excavations where humain remains were discovered, burial mounds, burial caves, and stone cairns in the Shenandoah Valley. Tribal traditions provide evidence of where ancestors were buried as well, especially in places occupied steadily since tribal groups wre displaced in the 1600's and 1700's from ther original town sites. Native Americans are still being buried in Virginia, of course. As remains are placed in modern cemeteries and columbaria, those burial sites are fully documented.

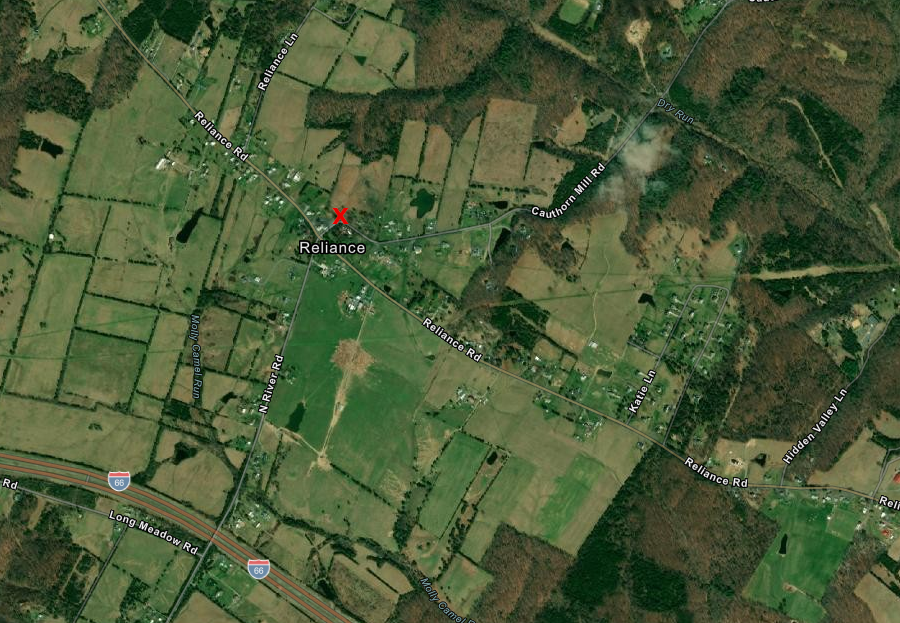

In Warren County, local residents assume that a modern grave is the burial site of an "Indian." In the 1960', oral tradition identified a "simple, unmarked, square concrete headstone located between the graves of two members of the Rosenberry family" in Old Providence Church graveyard in Reliance as the grave of an Indian. He presumably had been buried there in the late 1800s or early 1900s. A copper plate with the profile of a Natve American man was added to the concrete headstone to identify his presumed heritage.19

the "Indian" burial at the Old Providence Church graveyard in Warren County was marked with a copper plate in the 1960's

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online