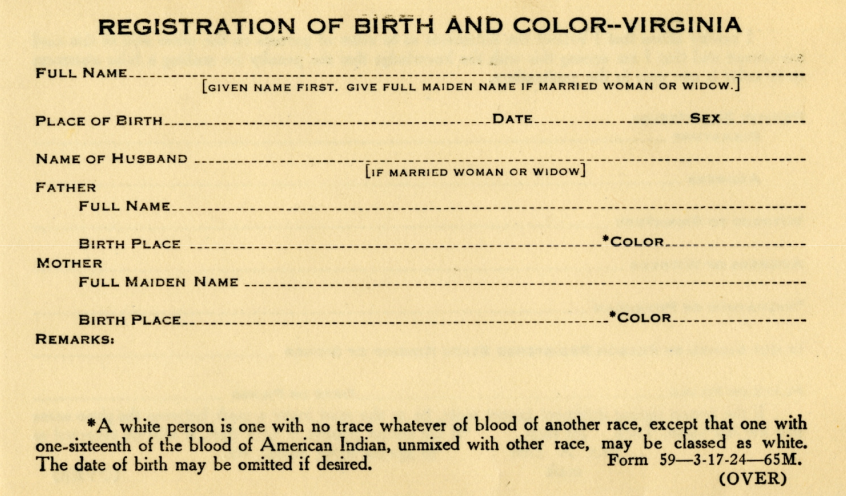

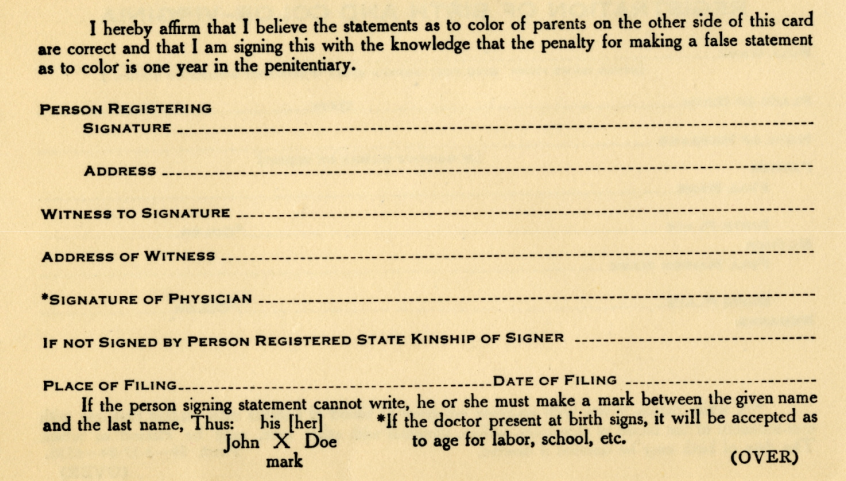

as registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics, Dr. Plecker emphasized that everyone in Virginia should be classified as colored or white, not as Indian

Source: Library of Virginia, Registration of Birth and Color, 1924

as registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics, Dr. Plecker emphasized that everyone in Virginia should be classified as colored or white, not as Indian

Source: Library of Virginia, Registration of Birth and Color, 1924

The original inhabitants of Virginia looked very different from the European immigrants who started arriving after Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue in 1492. The Africans brought to Virginia in colonial times were easily distinguished from both Europeans and Native Americans - initially. However, once people of different races produced mixed offspring with a range of skin colors and facial features, the ability to distinguish someone's "race" just from appearance became more challenging.

Offspring of whites and blacks ended up being categorized based on the status of the mother. All children of female slaves inherited the status of slavery, no matter what the status of the father. Children of a free black mother gained status as a free person of color. Mixed-race children with a white mother faced discrimination, but were not consigned to slavery. Native Americans used different criteria, and considered a child of a Native American father or mother to be "Indian."

Colonial leaders began formalizing race-based slavery after the first Africans were brought to Hampton in 1619. The process of creating a legal framework for chattel slavery was not straightforward. Multiple court decisions were made and laws were passed starting in 1661 that ultimately restricted the rights of people who were defined as "negro" or "Indian" rather than "white."

The differences in racial status was made clear in 1630. A male colonist was sentenced to be "soundly whipt" after being caught "defiling his body in lying with a negro."

Traditions established the patterns of slavery before they were codified by laws. For example, starting in 1640 only Negroes were prohibited from owning firearms.

Indentured white servants who fled their owners were, after being caught, punished differently than black people who fled. On March 1, 1661 (1660 in the Old Calendar used in the colony until 1752), the General Assembly passed a law entitled "English running away with negroes." At the time, some black servants were indentured for a term of service while others were automatically enslaved for life. That law formally acknowledged that there were blacks who were already obliged to work for their entire life, so they could not be punished by adding to their term of service like white indentured servants.

In 1662, the General Assembly passed "Negro womens children to serve according to the condition of the mother," a law clarifying that the children of enslaved mothers would also be enslaved for their entire lifetime:1

Later legislation made clear that children born by enslaved mothers would stay enslaved for life even if they adopted Christianity and were baptized. By the time the Slave Codes of 1705 were passed, the subordinate status of black people was clearly locked in by both law and custom.

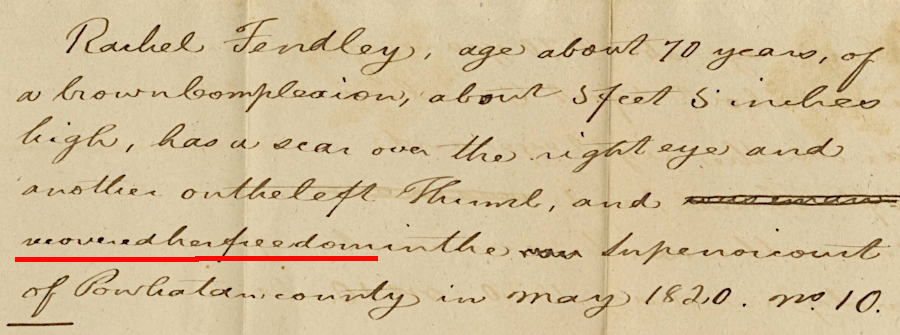

The status of Native Americans remained more ambiguous. In 1662, the General Assembly passed a law requiring the length of indentured service be the same for Indians as for indentured English servants, prohibiting lifetime enslavement for Native Americans. In 1773, an enslaved woman named Rachel succeeded in getting the Powhatan County court to rule in a "freedom suit" that she and her children were descendants of a Indian mother. As such, they were all free and could not be held in bondage.

To prevent the loss of his "property," Rachel and some of her children was taken to Wythe County and sold to a new owner. Her subsequent children were also kept in slavery. It took another 47 years and more legal action before Rachel Findley obtained another ruling by the Powhatan County court that she and all her children were free people of color because of her Native American ancestor.

Rachel Findley "recovered her freedom" and that of her children because she was descended from a Native American woman

Source: Library of Virginia, "Descendants of a Woman of Indian Extraction": The Story Of Rachel Findley (August 31, 2022)

The existence of a category other than white or black caused great difficulty during the era of government-enforced segregation, when racial status defined one's right to eat in a restaurant, sit on a bus, or attend school. In 1924, Virginia officials sought to cut through the confusion and eliminate the potential for light-skinned blacks to "pass" as whites, by categorizing any child with one drop of black ancestry as a black person.

As modern society has come to appreciate diversity, it has also become more realistic to consider whether any family or community is of any pure race. After all, every human alive today can trace their ancestry back to migrants who moved out of Africa some 60,000-90,000 years ago. If it were possible for every person on earth to trace their genealogy back as much as 4,500 generations, their ancestors would have been living in Africa.2

There's a modern anthropology term, tri-racial isolate, for people whose racial origins are not clear and who may be a blend of white, black, and Indian ancestry. The Melungeon families in southwestern Virginia and Tennessee are often categorized by scientists as a mixed community, with genes from various races - though some members of those families strenuously argue that their true heritage is from Portuguese or Turkish sailors and Native Americans, and there is little or no intermixing with black ancestors.

For centuries, Virginia law defined race in just a handful of categories - white, black, free people of color, Indian. Legal and social discrimination has provided strong incentives for various groups to minimize or obscure any genetic relationship with blacks in particular.

In 1887, the Virginia legislature defined who would be classified as a "colored person" or "Indian:"3

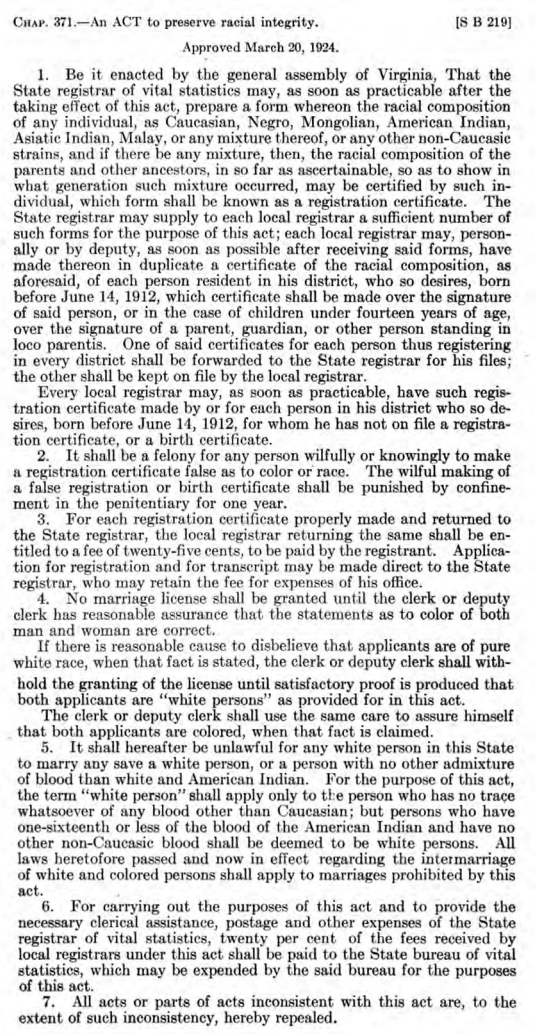

That definition was revised in 1910 to classify anyone have one-sixteenth or more of negro blood as a "colored person." The 1924 Racial Integrity Act restricted the "white" classification to just those with no trace of non-white heritage. Only "pure white race" Caucasians could be treated under Virginia's segregation laws as "white." Those laws blocked non-whites from marrying "whites," riding in white-only railroad cars, or attending "white" schools.

The Bureau of Vital Statistics was created in 1912, and tasked with recording the racial status of all Virginians. Dr. Walter Plecker served as the first registrar.

He sought to define "pure" whites based on the theory of eugenics. White supremacy standards were codified by the General Assembly in the 1924 Racial Integrity Act:4

after signing the Racial Integrity Act in 1924, Governor E. Lee Trinkle quicky registered his family as "white"

Source: UnCommonwealth blog, Library of Virginia, The Impact Of The Act To Preserve Racial Integrity On Virginia's Indigenous Tribes

By the initial interpretation of the 1924 law, any non-white ancestor - no matter how many generations ago - would disqualify someone from being white. One drop of Negro blood would cause a person to be categorized as colored. Plecker actively encouraged local and state officials to consider all people with a mixed-race heritage as "colored," since in his opinion any non-white heritage disqualified a person from being "white."

According to Plecker, those who might be described as mulatto or Indian were non-white, and anyone who was not classified as white had to be classified as black. He contended that the Native American tribes had lost what he considered to be their racial integrity, and were no longer a distinct group.

There was no middle ground, no mixed-race status authorized by the 1924 law, with just one exception made for some "white" descendants of Pocahontas. The fear of Plecker and the racists in the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America who supported him was that 10,000-20,000 Virginians who were "near white" but had one drop of Negro blood would behave differently, and:5

Dr. Walter Plecker actively used his position in state government to preserve what he considered to be "pure" white heritage

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia Health Bulletin: The New Virginia Law To Preserve Racial Integrity, March 1924

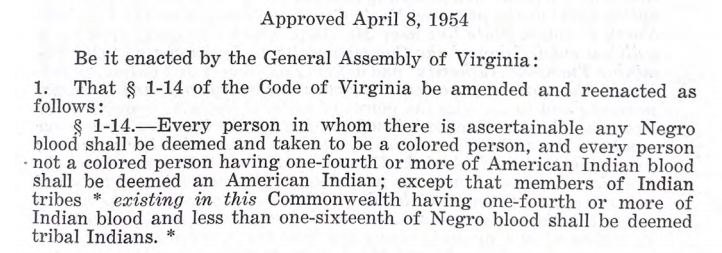

Dr. Plecker sought to categorize many of the Indians in Virginia as black in order to stop light-skinned people with black ancestry from passing as white people and thus avoiding the Jim Crow discrimination laws. However, he was unable to use the equivalent of "one drop" of Native American blood categorize someone automatically as Indian:6

Plecker's one-drop rule was constrained by so-called First Families of Virginia (FFV's). They traced their ancestry back to Thomas Rolfe, the son of Pocahontas and John Rolfe, and were proud of their connection to what they considered to be Native American royalty. As described by one member of the Virginia elite:7

As a result, Virginians whose ancestry was one-sixteenth Native American or less were declared to be "white" in the Racial Integrity Law of 1924. Whites could not have one drop of black blood, but they could have a Native American grandparent. That 1/16th "loophole" enabled descendants of Pocahontas to remain within white society, unaffected by the Jim Crow laws requiring segregation of the races.

baptism of Pocahontas in 1614

Source: Library of Congress, America as a Religious Refuge: The Seventeenth Century

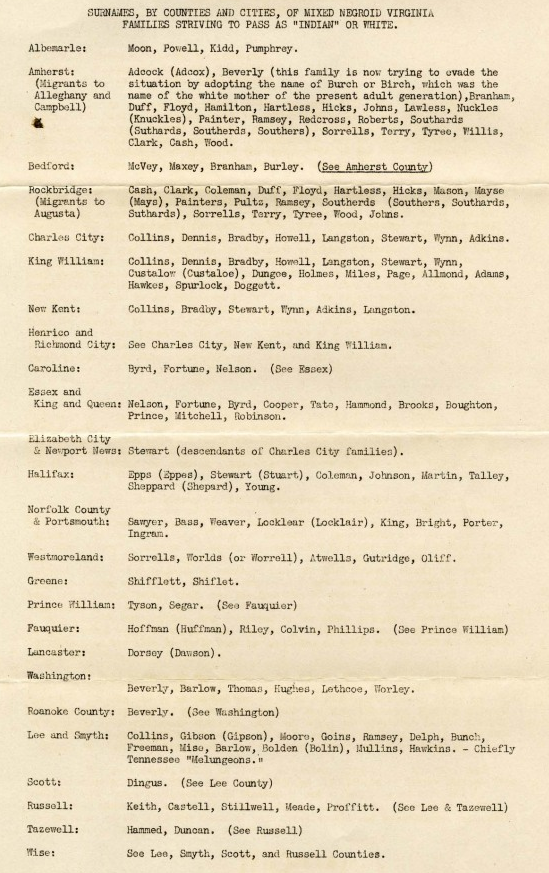

Plecker served as Virginia's registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics between 1912-1946. Plecker created lists of families that he considered to be colored, but who were attempting to define themselves as "white" by claiming that the only mixing in their family tree was with Native Americans. He wanted to ensure those trying to "pass" as white did not receive the privileges of white people in Virginia's segregated society.

As described in one review of his career:8

Dr. Walter Plecker alerted local officials to block people with mixed racial heritage from passing as "white"

Source: Virginia Memory, Who Do You Love?: Race And Marriage In Virginia Before The Loving Decision

Plecker justified his actions by citing the science associated with eugenics. He was extreme in his approach, including trying to force children from an orphanage because he assumed their illegitimate birth was also an indicator that they had "negro blood." He even tried to have bodies removed from a cemetery reserved for whites.

As further research drew into question the assumptions of eugenics, some advocates shifted to justifications based on white supremacy. Plecker was forced to admit the lack of any scientific basis for his actions once, when he was blocked from changing the birth certificate of a woman classified as "Indian" before 1924. He wrote his primary supporter for his efforts at racial discrimination:9

Plecker retired in 1946 when he was 85 years old. A year later he was hit by a car while crossing a street in Richmond, and died on August 2, 1947. The race of the driver is unknown. Obituaries in the major newspapers highlighted his life with positive comments. In papers with an African-American readership, the obituaries were far less complimentary.

The Richmond Afro-American observed:10

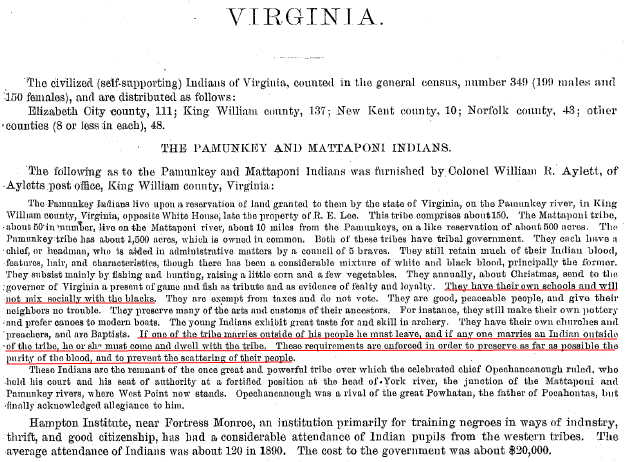

Long before Plecker, the Native American tribes had rejected the idea of just two races existing in Virginia, and sought to maintain their distinctive status as "Indians." After the Nat Turner insurrection in 1831, white Virginians increased suppression of free people of color.

That motivated the Chickahominy to obtain county-issued certificates of free birth, while the Nansemond got a new state law passed allowing them to get certificates as persons of mixed blood, not being free negroes or mulattoes. Some Pamunkey documented their status with "certificates of freedom," and in 1843 successfully rebuffed an effort to abolish what are today the Pamunkey and Mattaponi reservations because intermarriage with Negroes supposedly had eliminated their Indian character.11

Helen Rountree notes that after 1865, when inter-racial worship largely ended, the Pamunkeys established their own Baptist church separate from both white and black churches. When Virginia established a free public school system starting in 1870, separate schools were built and staffed for blacks and whites (with the white schools being far better funded).

White county officials steered the Pamunkey, Chickahominy, and other Native Americans to the black schools. However, Native Americans struggled to gain access to the white schools, or to create a third set of schools separate from both blacks and whites. Roundtree states:12

As noted in the 1890 Census regarding the Pamunkey tribe:13

1890 Census report on Virginia Indians

Source: Bureau of Census, 1890 Census, Volume 10: Report on Indians Taxed and Indians Not Taxed in the United States (except Alaska)

At the start of World War II, the Selective Service drafted men based on race. There were specific quotas for black and white men, with black draftees assigned to "colored" units in the military. Those men who draft boards did not classified as black were treated as whites, and members of various Native American tribes were assigned to "white" units together with Caucasian men.

During World War I, before passage of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, Native Americans from Virginia served with white units. To meet the requirement to classify draftees by race for World War II and to comply with Virginia law in 1940, state and local officials in Virginia decided that Native Americans with at least one-quarter Indian blood and "no ascertainable negro blood" would be classified as "white" but all others would be classified as "colored."

The Pamunkey and Mattaponi, the two tribes in Virginia with established reservations, appealed successfully and were classified as whites by the local draft boards. In Amherst County, Monacans (then referred to as "Issues") won a Federal lawsuit and were classified as "white." Some Chickahominy men were inducted as "colored," but managed to be reclassified as "white." Some Rappahannocks refused to appear for induction after being classified as "colored," but were later allowed to serve as conscientious objectors and bypassed being assigned to "white" or "colored" units.

Selective Service officials working for the Federal government, declared that inductees were entitled to designate their race. Federal judges affirmed that self-identification was valid, and the Selective Service lacked authority to reclassify inductees. At one point, for several months, draft boards forwarded inductees to US Army bases and tasked military officials to choose whether the men would be assigned to "white" or "colored" units. Military officials refused the assignment and returned those inductees. Native Americans in Virginia successfully blocked eing assigned involuntarily to "colored" units in World War II.14

Dr. Helen Roundtree's assessment of the civil rights struggle distinguishes the activist role of blacks vs. Native Americans:15

Modern Native American leaders in Virginia consider Plecker to be a villain. He was working to extinguish a group's identity, to deny their existence, following the same eugenics and racist philosophies used by Hitler in his effort to exterminate minorities in Europe. In 2015, commenting on the day Plecker was hit by a car in 1947 (a year after he had retired), the chief of the Chickahominy stated:16

even after Plecker died, the Virginia General Assembly continued to define the racial mix required to be declared a tribal Indian in Virginia

Source: Commission to Examine Racial Inequity in Virginia Law, From Virginia's law books (Exhibit 12)

Race is a socially constructed concept rather than a biologically-based distinction. Racial classifications are redefined for different purposes by different generations. Virginia's Jim Crow laws establishing segregation were designed in large part to minimize the potential for inter-racial socializing, especially the sort that could lead to children. The post-Civil War Readjuster coalition between blacks and whites was broken in 1883 when opponents were able to scare white voters into thinking black political power was just a precursor to demands for social equality and miscegenation.17

Times have obviously changed. If race is based on continental ancestry and genetic isolation, then groupings like African, Caucasian (Europe and Middle East), Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native American make less and less sense as massive migrations result in genetic mixing.

After the Supreme Court ruled in 1954 in Brown vs. Board of Education that segregated schools violated the US Constitution, efforts by segregationists to stir race mixing fears lacked the political impact of 1883, and ultimately failed to block school desegregation even in Prince Edward County. During the Massive Resistance debate on how to respond to that Supreme Court decision, a focus on the doctrine of "interposition" allowed Virginia's political leaders to oppose integration based on philosophical grounds without having to justify state-sponsored social inequalities.

In Virginia, government controls to define and maintain racial purity have largely been replaced by officially-sponsored celebrations of diversity, though some Native American groups are still using "blood quantum" to help determine who will be classified as a tribal member.

In the 2010 Census, individuals could choose multiple racial categories for themselves. "Hispanic" was an ethnic category separate from race.

By 2010, approximately 15% of first marriages in the United States were between spouses of a different race or ethnicity, doubling the percentage since 1980. Virginia was the #1 state for new white/black marriages (3.3%).18

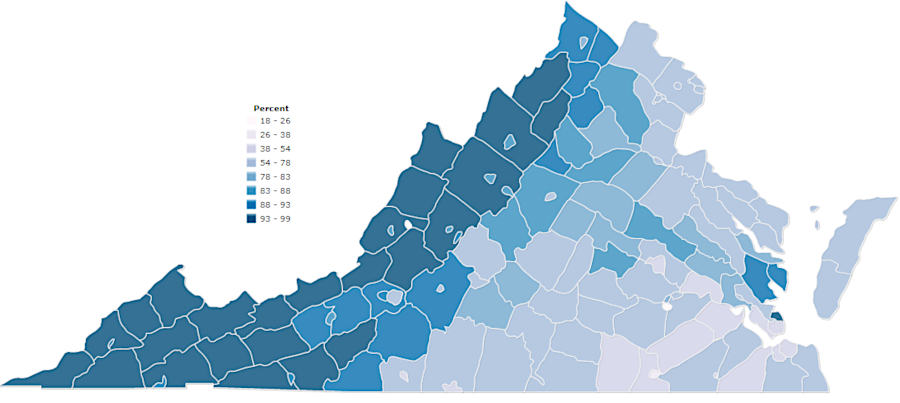

the percentage of residents identifying as "white-only" varies across Virginia

Source: IndexMundi, Virginia White Population Percentage, 2013 by County

"the Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics did genealogical research to proactively block "negroes" and "Indians" from registering as "white"

Source: Encyclopedia Virginia, Letter from Walter A. Plecker to Local Registrars, et al. (December 1943)

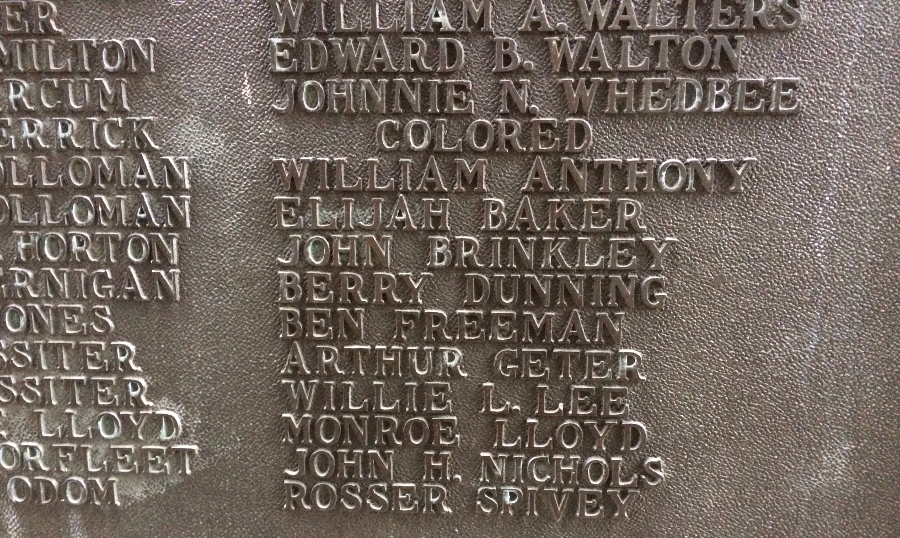

the monument honoring World War I veterans at Suffolk's Cedar Hill Cemetery identified those who died in the war by race

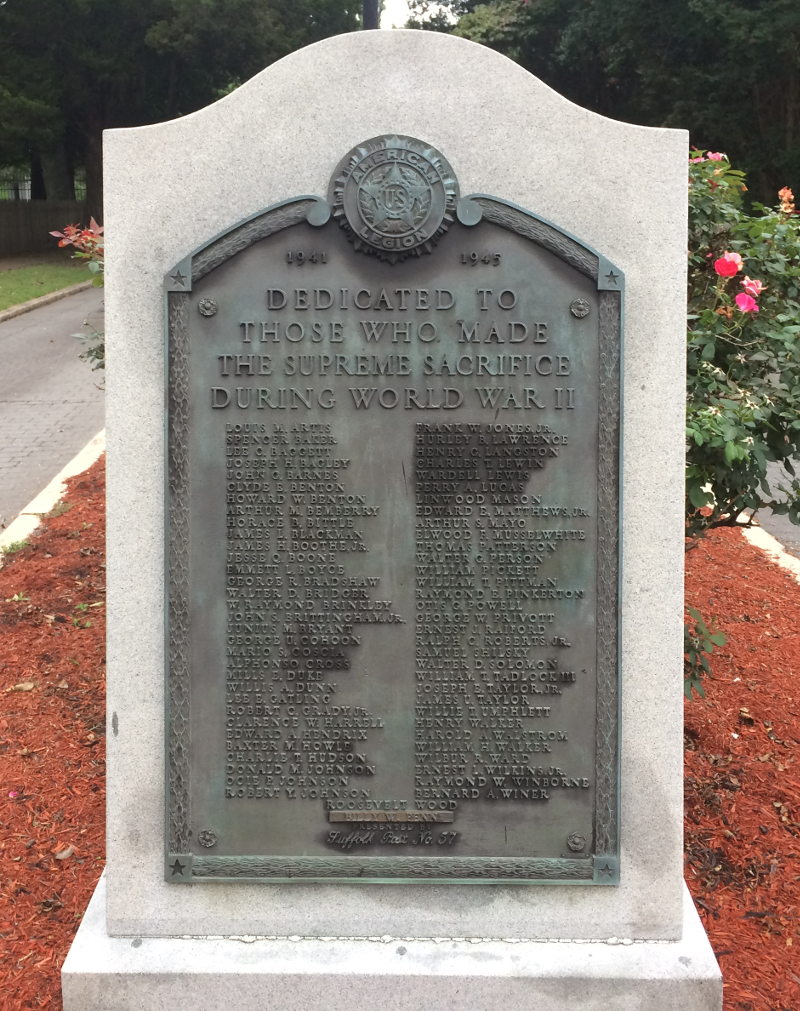

by the time the monument honoring World War II veterans was installed at Suffolk's Cedar Hill Cemetery, it was no longer considered appropriate to segregate war dead by race

the 1924 one-drop law passed by the Virginia General Assembly

Source: Commission to Examine Racial Inequity in Virginia Law, From Virginia's law books (Exhibit 1)