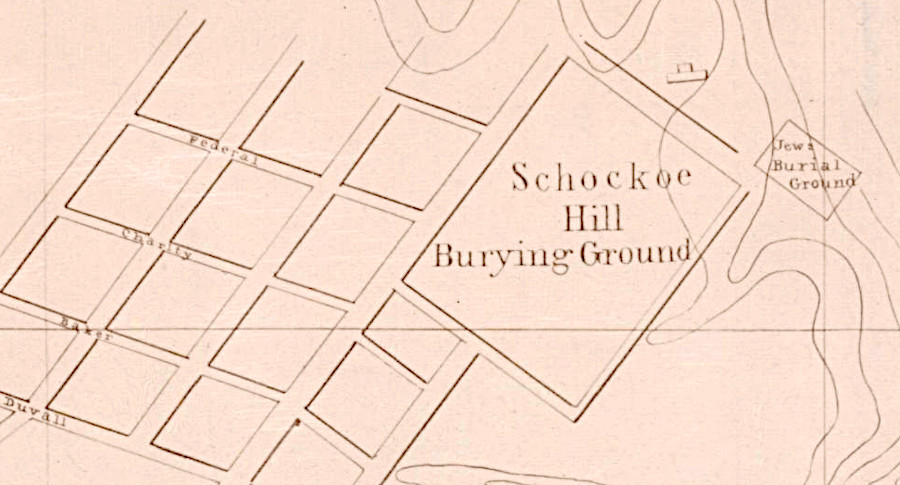

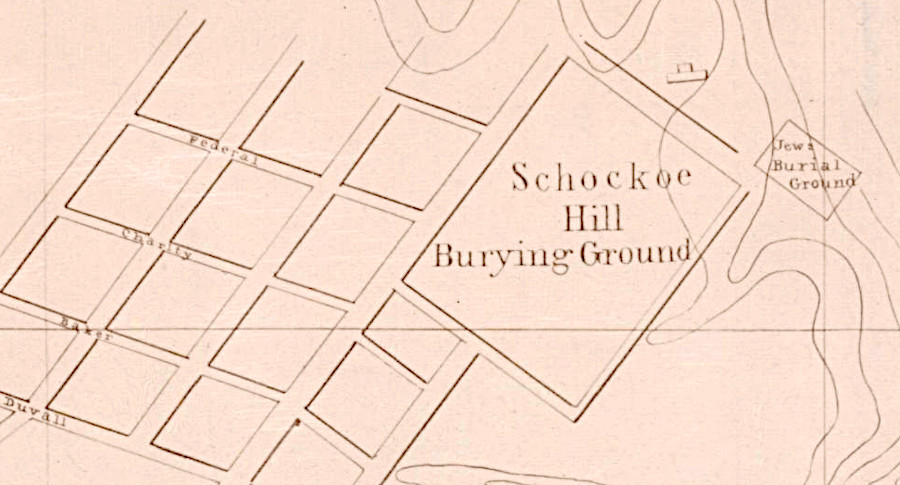

as in many communities, a separate cemetery was set aside in Richmond to bury the Jewish dead

Source: National Archives, Map of City of Richmond, Virginia (c.1858); Virginia Comonwealth University, Baist Atlas of Richmond, VA (1899)

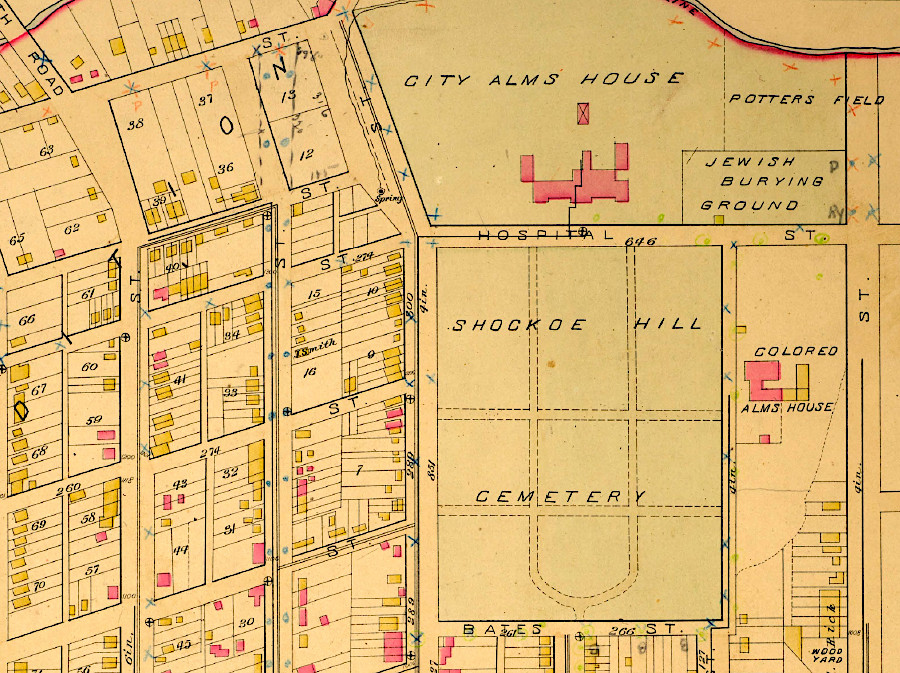

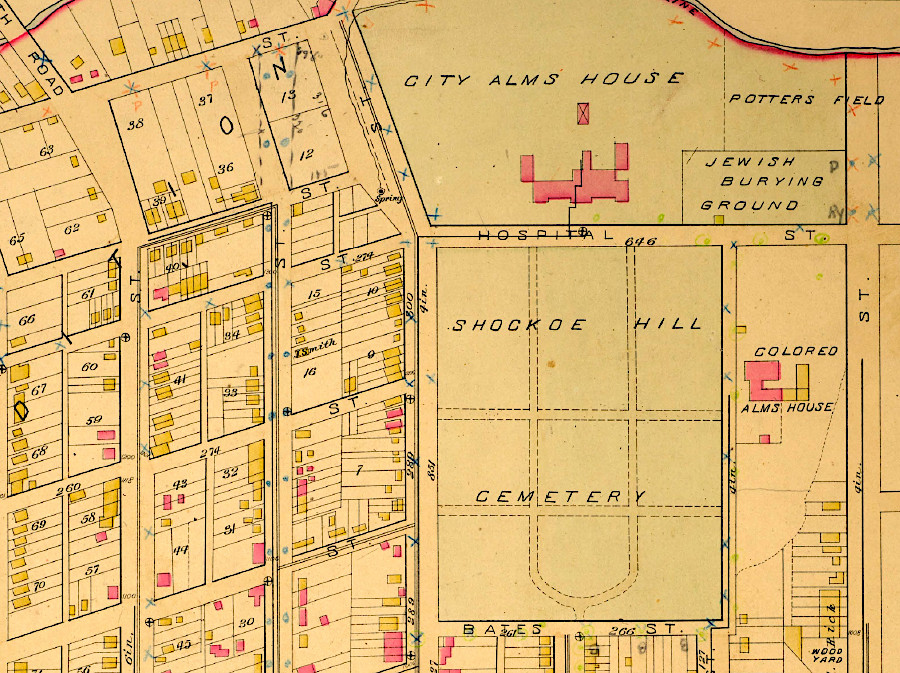

as in many communities, a separate cemetery was set aside in Richmond to bury the Jewish dead

Source: National Archives, Map of City of Richmond, Virginia (c.1858); Virginia Comonwealth University, Baist Atlas of Richmond, VA (1899)

The first Jew to visit Virginia may have been a sailor on one of the Spanish expeditions along the coastline.

The first documented resident was Joachim Gans, whose name is also spelled Ganz, Gaunse, and in other ways. Gans was born in Prague and came to England in 1581 to work in copper mining. He joined the Ralph Lane expedition and reached Roanoke Island in 1585.

Gans had been recruited to join Sir Walter Raleigh's colony for his technical skills in identifying ore and smelting metal. The English saw Native Americans wearing items made from copper in 1584, and anticipated discovering minerals in North America comparable to the Spanish success in Central and South America.

The technical expertise of Joachim Gans with metal was more important to Sir Walter Raleigh than his religion, though Gans may not have advertised his beliefs at the time. Ralph Lane did not record that he had a Jew among his colonists, so Gans may have behaved like all the others during religious services. He may have hidden the fact that he was circumcised.

Joachim Gans and Thomas Harriot built a science lab on the island. Harriot examined plants. Gans tested copper obtained from the local residents and smelted ore samples, hoping to identify copper, gold, or other minerals that would make the colony profitable. In the winter of 1585-86, he apparently traveled north to Lynnhaven Bay and the Elizabeth River as the colonists sought to find a better location and the source of the Native American copper.

Gans' metallurgical operations may have been constrained because some of the equipment he brought did not make it to the island. If he had brought an assay oven for smelting samples at temperatures as high as 2,000°F, it and other heavy items were tossed overboard when Sir Richard Grenville's flagship Tyger ran aground while trying to navigate through an Outer Banks inlet to Roanoke Sound.

In 1586, Gans returned to England when the colonists hopped on the visiting ships of Sir Francis Drake and abandoned Roanoke Island. He was not part of the "Lost Colony," the colonists who arrived in 1587 and were never seen again.

The science workshop on Roanoke Island was excavated by archeologists in the 1990's. They found evidence of crucibles with traces of molten materials including silver, iron, and copper, plus bricks from the high-temperature furnace that Gans built to smelt samples. The traces of minerals may have come from smelting jewelry worn by the local Native Americans. Those items had been acquired by trade from sources close to the Great Lakes, rather than from Native Americas smelting Carolina ore. The site of Gans's research laboratory is preserved today by the National Park Service at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

The religion of Gans, the first Jew to live in "Virginia," was exposed after he returned to England in 1586. He was arrested in Bristol in 1589 and admitted to being a circumcised Jew. A trial was planned in London, but apparently Gans' connections with influential people blocked a trial from ever being held.1

The first Jews to live openly in North America came from Recife, Brazil in 1654. The Portuguese seized Recife from the Dutch and expelled the Jews which the Dutch had allowed to live there. The refugees came to New Amsterdam. After the British took control and renamed the place New York, the Jews were allowed to remain.2

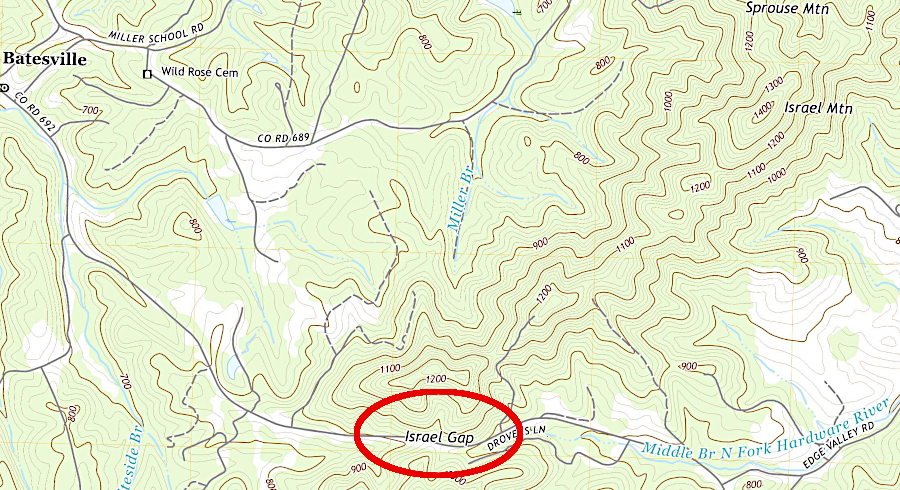

Colonial officials in Virginia expelled Puritans and Quakers, but it appears Jews who immigrated to Virginia as early as the 1650's managed to stay. There were no organized Jewish congregations until after the American Revolution, but there were Jewish residents. Israel Gap in Albemarle County, west of Charlottesville, is named for Michael and Sarah Israel. They bought 80 acres there in 1757.3

one acre for the Hebrew Cemetery in Richmond was purchased in 1816

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Covesville, VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2019)

The first Jewish congregation to be organized in Virginia was Kahal Kadosh Beth Shalome. It was founded by 29 men in 1789, after the General Assembly passed the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786.

K. K. Beth Shalome was one of the six Jewish congregations in the United States to offer formal congratulations to George Washington when he was inaugurated as President. A burial ground for Jews was created in 1791. When it filled up, an acre was purchased on Fourth Street in 1816 to establish the Hebrew Cemetery. The synagogue at 115 Mayo Street opened in 1822.

one acre for the Hebrew Cemetery in Richmond was purchased in 1816

Source: GoogleMaps

City voters elected Jewish men to different positions starting in 1793, when Jacob Cohen was elected to City Council. Gustavus A. Myers served on Richmond's City Council for nearly three decades. The Jews in Richmond were primarily traders and merchants, not plantation owners, but they owned slaves in roughly the same percentage as other residents in the city. Prior to the Civil War, Jewish leaders supported slavery and were not abolitionists.

The Richmond congregation split in 1841. K. K. Beth Shalome remained a Sephardic house of worship, while German Jews organized Beth Ahabah as a community for Ashkenazi Jews. William Thalhimer, who organized his department store in 1842, moved to Beth Ahabah.

That congregation opened Richmond's first school to educate Jewish children (and others as well) in 1846. Beth Ahabah built its synagogue in 1848 at Eleventh and Marshall streets. It became a Reform congregation in 1875, rebuilt a larger synagogue on Eleventh Street in 1880, and moved to its current location at 1117 W. Franklin St in 1904.

Polish Jews organized the Keneseth Israel congregation in 1856, and Russian Jews organized the Sir Moses Montefiore Congregation in 1880. Both later consolidated with the Aitz Chaim congregation to establish the Orthodox Temple Beth Israel.

In 1898, those members of Kahal Kadosh Beth Shalome still living in Richmond after the Civil War rejoined Beth Ahabah, which is still the city's largest Reform congregation. The original synagogue building on Mayo Street was demolished in 1932.4

Moses and Eliza Myers came to Norfolk in 1787, where he started an import-export business. It thrived, and he was elected to Norfolk's Common Council in 1795. A Jewish cemetery was established in 1819, but the few graves within it were moved to a larger Jewish cemetery that was created in 1850.

In the 1840's, immigration from Germany led to an increase in the number of Jews in Tidewater as well as in Richmond. The House of Jacob was organized in 1848, and the synagogue opened in 1859. The congregation was renamed Ohef Sholom in 1867.

The Ohef Sholom congregation split in 1870, as it adopted more Reformed Judaism practices. Conservative Jews formed Congregation Beth El. Both groups contended they controlled the Hebrew Cemetery. Until they negotiated how to work together in 1880, each tried to block the burial of members from the other congregation. Reportedly at least one person was buried at midnight, in order to avoid any disruption of the service by the other congregation. The City of Norfolk took responsibility for the Hebrew Cemetery in 1957; it is managed now by the city's Bureau of Cemeteries.5

for a decade, the Ohef Sholom and Beth El congregations fought over control of the cemetery in Norfolk

Source: City of Norfolk, aerial photo of Hebrew Cemetery

As immigration continued in the 1800's, new Jewish congregations were established in Tidewater and urban centers across the state: 6

Congregation Rodef Sholom was formed in Petersburg in 1858; Congregation Beth El was organized in Alexandria in 1859; the Hebrew Friendship Congregation was established in Harrisonburg in 1870; Major Alexander Hart helped to establish the House of Israel Congregation in Staunton in 1876; Danville's Beth Sholem Congregation was founded in 1881; in Newport News, organization of the synagogue was in 1887; Portsmouth's Congregation Adath Jeshurun was organized in 1893; Roanoke's Temple Emmanuel was organized in 1897; and Congregation Agudath Achim was founded in Lynchburg the same year.

The first Jew to be elected to the General Assembly was Benjamin Banks in 1912. In 2020, the top leaders in the General Assembly were Jewish. In 2008, Dick Saslaw was elected as the Minority Leader of the Democrats in the State Senate. After that party won a majority in the 2019 elections, he became Majority Leader.

At the start of 2019, Democrats in the House of Delegates elected Del. Eileen Filler-Corn to serve as the first Jewish Minority Leader. When Democrats won control of the House of Delegates in the November elections, she became the first Jew as well as the first woman to serve as Speaker of the House.7

What the two leaders shared in common, and though the Democratic Party controlled both houses, did not overcome the institutional rivalries between the House of Delegates and the State Senate. The two houses in the legislature struggled to adopt common positions for marijuana, criminal justice reform and regulating electric utilities. An experienced commentator for the Richmond Times-Dispatch compared the Democratic legislative majority to "a large, argumentative Jewish family."8