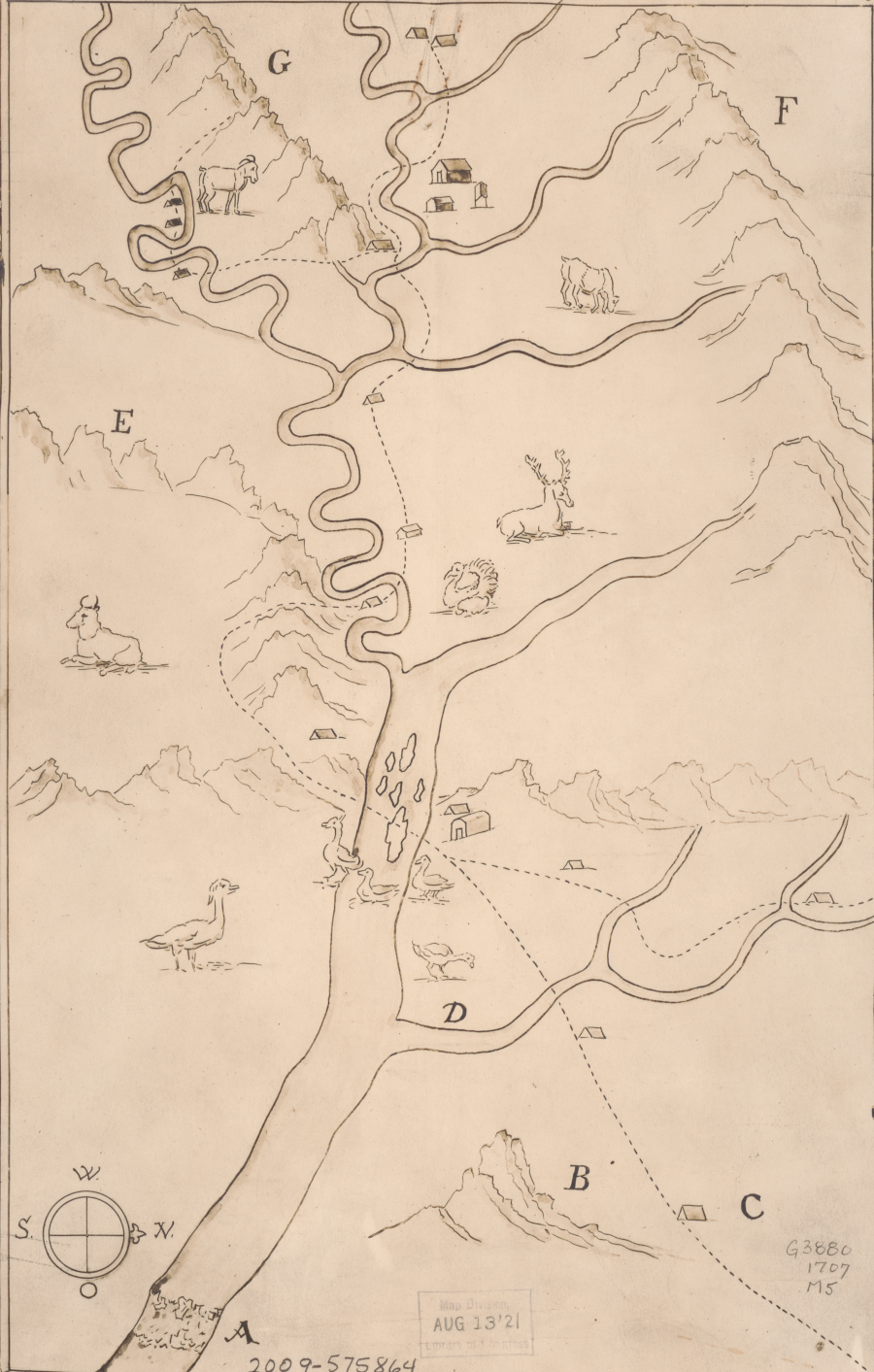

Franz Ludwig Michel was the first European to map the pattern of rivers and mountains in the Shenandoah Valley

Source: Library of Congress, Michel's map: 1707 (by Franz Louis Michel, 1707)

Franz Ludwig Michel came to Virginia prepared to acquire land for himself and/or acting as an agent for the Bern canton of Switzerland. Michel's father was a prominent official in Bern. Bern officials sought land in order to deport their unpopular religious dissidents to Virginia.

For 150 years since John Calvin brought his Protestant faith to Switzerland, Swiss officials had sought to repress Mennonites and other Anabaptists and enforce religious uniformity. In addition to holding different views on baptism and other religious customs, the Anabaptists were a problem for Swiss officials because they objected to conscription and paying taxes for the military.

In 1699, Bern created an Anabaptist Bureau to persecute and banish the dissidents. A 1699 attempt to send the Anabaptists to India failed when the East India Company declined to respond to the proposal. Michel came to Virginia to see if land could be acquired cheaply there, so the Mennonites and other Anabaptists could be exported to an English colony.2

Michel left Basle, Switzerland on October 8, 1701. After a stay in London, he reached Yorktown on April 8, 1702. He met with Governor Francis Nicholson and Colonial Secretary Edmund Jenings, who were looking for ways to protect the western edge of English settlement from Native American raids and potentially French incursion. In 1701 the General Assembly had passed a law designed to stimulate new western settlements. It authorized grants of 200 acres for each settler to create:3

- ...cohabitations upon the said land frontiers within this government, and that the best method to effect the same will be by encouragements to induce soeietys of men to undertake the same, and wheras a less number than twenty able fighting men is not thought a sufficient defence in such cohabitations...

The first possibility Michel considered was land owned by the College of William and Mary, which originally had been granted in 1618 for the college planned at Henricus. James Blair offered a three-year exemption from local taxes. Michel did not accept that offer.

In company with two Frenchmen which he had met on the trip across the ocean, Michel explored west to the edge of colonial settlement. The three men rented horses and searched for Huguenots from France and Switzerland, Protestant refugees who had reached Virginia in 1699. King Louis XIV had revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1785, forcing Protestants in France to become Catholics or leave the country.

Michel found some Huguenots living along the Mattaponi River, including four sisters from Bern. He concluded that the terms of land acquisition there would be too burdensome.

Michel and his two partners explored westward by going up the James River from the Fall Line. At the time, there were no settlements between Falling Creek and Manakin; Richmond had not been founded yet. The best directional guidance Michel received was to keep the James River on his right until he bumped into the Huguenots living on the south bank of the river at Manakin. The party was also warned to beware of the "savages" they might encounter.

After reaching Manakin, Michel recognized a settler he knew who had come from a Swiss canton north of Basle. The soil was highly productive, the French-speaking settlement was thriving, the Monacans were trading peacefully, and the church services were consistent with Michel's beliefs. He decided to buy land next to the Huguenots living at Manakin. Michel and four French families petitioned Governor Francis Nicholson for personal land grants on the same terms the Huguenots were given in 1699 and 1700. The grant was approved, including a seven-year exemption from paying annual taxes.

Michel had planned to spend a year exploring in America. After acquiring the land at Manakin, he tried to catch a ride on a ship traveling from Yorktown to New York. He missed the connection, so he decided to walk alone to Philadelphia. He crossed through the Dragon Swamp, got lost several times, and at one point fainted from the heat.

He was warned by residents on the Northern Neck that travelers in colonial Virginia needed a "passport" issued by the governor to verify that they were not servants fleeing an indenture prematurely. For the few travelers in Virginia at the start of the 1700's, typically they visited the governor. If they impressed the governor with their wealth and status, he signed a passport. If a traveler skipped that step, then they were required to have their name read in church for three weeks before leaving the colony. Ship captains routinely complied with that requirement before boarding passengers. The announcements for three weeks allowed anyone with a claim for payment adequate time to come forward.

After reaching the Potomac River, Michel finally realized that travel into Maryland without a passport would be impossible:4

- ...the first man who would get a sight of me had power to demand my passport. He who does not have any, is jailed until a report has been received from the place whence he came. Whoever in such cases, he said, was strange and unknown and had none to inquire after him, would lose his liberty and his money, for he would have to pay half a crown a day.

Michel sailed home to Bern in 1702, after transferring his interest in the Manakin land to one of his French companions. He calculated the investment required for him to return and develop his land successfully would be low:5

- I regretted not a little that I was not sufficiently provided with means and hence compelled to return. About 400 dollars are necessary in order to set up a man properly, namely to enable him to buy two slaves, with whom in two years a beautiful farm can be cleared, because the trees are far apart. Afterwards the settler must be provided with cattle, a horse, costing at the usual price 4 lbs., a cow with calf 50 shillings, a mare 10 shillings. Furniture and clothes, together with tools and provisions for a year, must also be on hand. It is indeed possible to begin with less and succeed, but then three or four years pass by before one gets into a good condition.

Michel met with William Penn in London in 1703, ten returned to North America in 1704.6

Michel was not the only Swiss land speculator trying to get free land in exchange for bring new immigrants to America. He partnered with Georg Ritter, a wealthy man from Bern, and in 1705 submitted a proposal to the Bern officials for creating a Swiss colony in America. The proposal was forwarded to London, where the Lords of Trade took it under consideration. Michel traveled back to Virginia in 1706 and settled near modern-day Harper's Ferry.

The "Councill of Berne" initially thought the proposed Swiss Colony would be established in the West Indies, but the greater opportunity for a land grant was in North America. The petition from Michel and Ritter, for a new district in Virginia to be called Bern, requested Queen Anne to grant land which would be settled by:7

- ...four to five hundred persons, Switzers, Reformed Protestants, merchants, manufacturers, artisans, traders, as well as farmers...

Virginia had rich soil for agriculture, fine forests for shipbuilding, and known deposits of iron. The economic constraint limiting profitability of the American colonies at the start of the Eighteenth Century was the shortage of labor.

Through successful displacement of the Native Americans from the Piedmont, there was more land available than could be cleared and farmed by the existing colonists. Inadequate transportation west of the Fall Line made that land undesirable. In their petitions for free land and other subsidies, the Swiss emphasized that they could speed up settlement of the inland areas by importing new immigrants.

Georg Ritter renewed the petition to Queen Anne in 1706. He requested that she pay for the transportation of the new settlers, that each of them be granted 100 acres, and that no taxes be collected for 10 years. Ritter also requested that the settlers be allowed to choose their own ministers, rather than be forced to worship under Anglican mininsters.8

Ritter never went to the colonies, and relied insytead upon Michel to identify where the new settlement should be established. Michel left from Annapolis in February 1707 on another exploration, and managed to explore the Potomac River beyond the Blue Ridge. Going south along the Shenandoah River, he may have reached the site of present-day Woodstock, Virginia.

Michel mapped the main stem of the Shenandoah River upstream from the mouth to Massanutten Mountain. His map indicated how the "bends" on the South Fork were different from the curving route of the North Fork.9

Native Americans reported Michel's exploration of lands west of the Blue Ridge to Pennsylvania officials. They said Michel and five companions claimed they were looking for mineral ore.

Michel appeared in person before the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania. He explained that he had permission from William Penn to search for land where a new settlement might be established.10

Ritter and Michel joined forces. Michel met with two of Ritter's key partners in London in 1708 - Christoph von Graffenried, an investor from Bern, and John Lawson, who had been appointed by the Proprietors as surveyor of the Carolina colony.

Michel and Christoph von Graffenried sent a petition to Queen Anne's officials in July, 1709. It noted that the French were occupying the Mississippi River Valley and could move east, so it would be in the interest of the English to settle allies on the "considerable tract of wild and uncultivated desert" at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers. The Swiss should be subsidized because that land:11

- ...in all probability will lye uncultivated and uninhabited for several ages which may prove of no good consequence to the Crown of Great Britain...

English officials sought more details regarding the proposed Swiss Colony, so Michel submitted the map in another petition. The petition with the map spurred a positive response. The Queen ordered the Governor of Virginia to grant land to the Swiss, and for her Secretary of State to document her support for the project.12

The Swiss and John Lawson organized a joint stock company and signed a contract with Bern in 1710 for shipping both paupers and Anabaptists. They chose to send them to Carolina. Queen Anne's officials had not agreed to provide free transportation, and the Proprietors of Carolina offered more generous terms than the Governor of Virginia or William Penn. In addition, the initial costs for a Swiss Colony in North America would be funded by Bern officials who were anxious to remove dissidents and the poor from their area.

The agreed-upon price was for Bern to pay the joint stock company 600 thalers to transport 101 paupers, plus 45 thalers per Mennonite or other Anabaptist put on board a transatlantic ship. Payment for the paupers may have covered most of the costs of the shipment, with payment for the Anabaptists providing the profits. Recognizing the risk that Anabaptists might slip off the boat and return to Bern, Ritter was provided only half the payment in advance for each Anabaptist loaded at Berne. The other half of the 45 thaler/person fee would be provided only after Ritter successfully shipped the Anabaptists from the Netherlands to America.

The Carolina Proprietors agreed to provide 10,000 acres of land. Expanding the population in the colony would increase economic activity and make the remaining land more valuable. Christoph von Graffenried purchased an additional 5,000 acres for himself. The feudal system envisioned by the Proprietors made him a "landgrave," and he chose to title himself as a "Baron of Bernburg."

In 1710 officials in Bern loaded about 100 paupers and 56 Mennonite men on a boat and sent it down the Rhine River towards Carolina. The deportation of the Mennonites did not get past the Netherlands; the Dutch were sympathetic to the Protestant sect. Rather than travel to an isolated colony in America, the Mennonites got off the boat and found co-religionists who would help them stay on the continent. Many moved to the Palatinate to join others of their faith.13

The paupers continued on the journey. They may have been willing to accept a free trip to leave Bern and start a new life in Carolina. The Dutch would protect fellow Protestants from a forced deportation based on religious discrimination, but had no objections to voluntary travel to America.14

In 1710, London was filled with German-speaking refugees who had fled the Rhine River Valley. Their farms had been disrupted by too many armies during the War of Spanish Succession, and the harsh winter of 1708-09 made many willing to gamble on a new life. In 1709 the Carolina Proprietors circulated three editions of A Complete and Detailed Report of the Renowned District of Carolina Located in English America, known as the "Golden Book" because of some gilt printing on the cover. It was written by Joshua Kocherthal, a minister hired to advertise the advantages of moving to Carolina.

The last edition included a letter from Kocherthal describing how Queen Anne had provided free transportation and land in New York to a group of migrants in 1708. Desperate farmers in the Rhine Valley assumed the Queen of England would do the same for them.

Christoph von Graffenried gathered 650 "poor Palatines" from England and transported them to Carolina, along with 150 Swiss refugees from Bern. The Baron, Franz Ludwig Michel, and John Lawson (Surveyor General of the Carolina colony) provided the immigrants land on the Neuse River. The leaders had joined together with George Ritter, another Swiss invester, and purchased about 15,000 acres from the Carolina Proprietors.

Graffenreid bought an additional 5,000 acres in his name, and the Proprietors then titled him "Landgrave of Carolina and Baron of Bernburg." Graffenried hoped that his colonists would become a source of skilled miners able to extract silver in Virginia, assuming that he could discover silver ore on the Potomac River.

The timing to create "New Bern" in Carolina was terrible. In 1711, Baron von Graffenried and Lawson were surveying along the Neuse River when they were captured by the Tuscarora. The Tuscarora executed Lawson, and revolted and killed most of the colonists at New Bern.

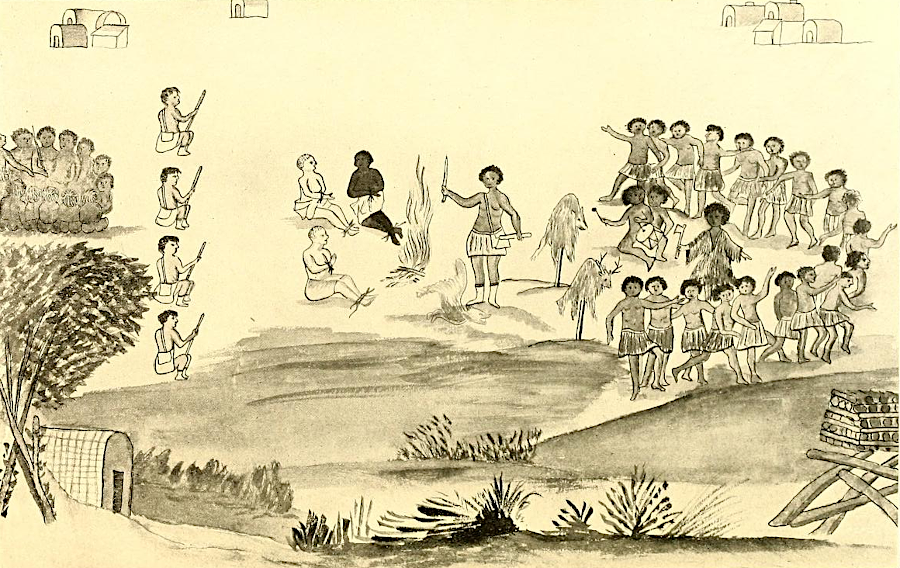

in 1711 the Tuscarora executed John Lawson, but Baron Christoph von Graffenreid was spared

Source: Baron Christoph von Graffenreid, The Graffenried manuscript C (after p.12 - drawing may have been done by Baron von Graffenreid)

Governor Spotswood of Virginia managed to arrange for Graffenried's release. Michel pressured Graffenried into using his personal credit to support the remaining New Bern colonists, after they and Michel declined Graffenried's proposal to move to Virginia.

The New Bern land speculation generated no revenue for Graffenried. He had to transfer the land to pay his debts, and the colonists were left on their own. Graffenried traveled to see Governor Spotswood in Virginia before returning to Europe in 1713. A year later, Spotswood was surprised to learn that Graffenried had sent a shipload of immigrants to Virginia and that Spotswood was responsible for paying for their transport. The governor sent them to land he owned on the Rapidan River, founding Germanna.

Michel apparently ended his association with Graffenried and stayed in Carolina. In 1712, Michel fought with South Carolina troops against the Tuscarora. He then disappeared from the historical records, but Graffenried indicates he "died among the Indians."15

Amish, Mennonites, and German Pietists in Virginia

Exploring Across the Blue Ridge

German Immigration into Virginia

Germanna

Silver in Virginia

Franz Ludwig Michel knew that John Lawson had explored the Carolinas

Source: A new voyage to Carolina (by John Lawson, 1709)

John Lawson mapped the future location of Bern, North Carolina (red X)

Source: North Carolina Maps, University of North Carolina, Lawson Map of North Carolina (by John Lawson, 1709)

Links

- Documenting the American South

- The Explorations of Louis Michel

- Internet Archive

- NCpdia

- Louis Michel

References

1. Alonzo Thomas Dill, "Michel, Frantz Ludwig," NCpedia, 1991, https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/michel-frantz-ludwig; Sir William Talbot (translator), The Discoveries of John Lederer, 1672, posted online by University of North Carolina, Research Laboratories of Archaeology, http://rla.unc.edu/archives/accounts/lederer/lederertext.html; "Batts and Fallam Expedition of 1671," West Virginia Archives and History, http://www.wvculture.org/history/settlement/battsandfallam01.html; "Th Explorer," Cooling Springs, https://www.coolingsprings.org/Cooling_Springs/1704.html (last checked March 22, 2024)2. "Bern (Switzerland)," Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Bern_(Switzerland) (last checked September 1, 2021)

3. William Waller Hening, "An act for the better strengthening the frontiers and discovering the approaches of an enemy," in The statutes at large; being a collection of all the laws of Virginia, from the first session of the legislature, in the year 1619, Volume 3, R. & W. & G. Bartow, 1823, pp.204-205, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hw2scr?urlappend=%3Bseq=195 (last checked September 8, 2021)

4. Wm. J. Hinke, "Report of the Journey of Francis Louis Michel from Berne, Switzerland, to Virginia, October 2, 1701-December 1, 1702. Part II," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 24, Number 2 (April 1916), pp.135-141, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243509; Frantz Ludwig Michel, "Arriving in Virginia; an excerpt from 'Short Report of the American Journey, Which Was Made from the 2nd of October of Last Year to the First of December of this Current Year 1702,'" Encyclopedia of Virginia, 1702, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/arriving-in-virginia-an-excerpt-from-short-report-of-the-american-journey-which-was-made-from-the-2nd-of-october-of-last-year-to-the-first-of-december-of-this-current-year-1702-by-frantz-ludwig-mi/ (last checked August 9, 2021)

5. Wm. J. Hinke, "Report of the Journey of Francis Louis Michel from Berne, Switzerland, to Virginia, October 2, 1701-December 1, 1702. Part II," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 24, Number 2 (April 1916), p.113, p.119, pp.121-124, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243509 (last checked August 9, 2021)

6. Robert A. Selig, "Wilhelmsburg," Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Volume 20, Number 4 (Summer 1998), https://www.ancestry.com/community/viewusercontent.aspx?uid=01d80517-0001-0000-0000-000000000000&type=story (last checked September 10, 2021)

7. "Documents Relating to Early Projected Swiss Colonies in the Valley of Virginia, 1706-1709," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 29, Number 1 (January, 1921), p.6, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243798 (last checked September 1, 2021)

8. "Documents Relating to Early Projected Swiss Colonies in the Valley of Virginia, 1706-1709," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 29, Number 1 (January, 1921), pp.6-8, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243798 (last checked September 1, 2021)

9. "The Explorations of Louis Michel," Potomac Appalachian Trail Club, https://www.patc.net/PATC/Library/PATC_-_History/Explorations_of_Louis_Michel.aspx; "Documents Relating to Early Projected Swiss Colonies in the Valley of Virginia, 1706-1709," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 29, Number 1 (January, 1921), p.4, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243798 (last checked September 1, 2021)

10. "Documents Relating to Early Projected Swiss Colonies in the Valley of Virginia, 1706-1709," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 29, Number 1 (January, 1921), pp.3-4, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243798 (last checked September 7, 2021)

11. "Documents Relating to Early Projected Swiss Colonies in the Valley of Virginia, 1706-1709," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 29, Number 1 (January, 1921), p.11, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243798 (last checked September 7, 2021)

12. "Documents Relating to Early Projected Swiss Colonies in the Valley of Virginia, 1706-1709," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 29, Number 1 (January, 1921), p.11, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4243798 (last checked September 7, 2021)

13. "Graffenried, Christoph, Baron Von," NCpedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/graffenried-christoph; "Bern (Switzerland)," Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Bern_(Switzerland) (last checked September 8, 2021)

14. Fred J. Allred, Alonzo T. Dill, "The Founding of New Bern: A Footnote," The North Carolina Historical Review, Volume 40, Number 3 (July, 1963), https://www.jstor.org/stable/23517645 (last checked August 9, 2021)

15. Alonzo Thomas Dill, "Michel, Frantz Ludwig," NCpedia, 1991, https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/michel-frantz-ludwig; Alonzo Thomas Dill, "Graffenried, Christoph, Baron Von," NCpedia, 1986, https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/graffenried-christoph; John Blankenbaker, "Germanna History," short note #557, http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~george/johnsgermnotes/germhs23.html; "Baron von Graffenreid and the Swiss Colony of New Bern," North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, https://www.ncdcr.gov/blog/2014/10/23/baron-degraffenreid-and-the-swiss-colony-of-new-bern (last checked October 9, 2021)

Exploring Land, Settling Frontiers

Virginia Places