Matchut/Matchot was located on the north bank of the Pamunkey River, perhaps upstream of the modern Route 360 bridge

Source: US Geological Survey, Manquin 7.5 topo (2010)

Matchut/Matchot was located on the north bank of the Pamunkey River, perhaps upstream of the modern Route 360 bridge

Source: US Geological Survey, Manquin 7.5 topo (2010)

By 1614, the English settlers had occupied much of the land along the James River and were beginning to establish farms on the York River. The land area of Tsenacommacah, the territory controlled by Powhatan, was hollowed out from the center as the English expanded outward from Jamestown.

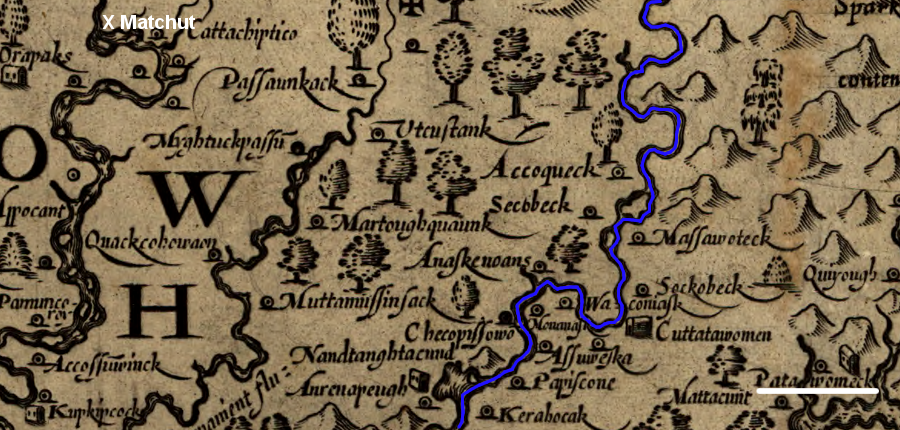

The paramount chief chose to move westward from his seat of power at Werowocomoco to Orapakes in 1609, two years after the English settled at Jamestown. He stayed there less than five years. Powhatan moved again, from Orapakes to Matchut (also spelled Matchot), sometime between 1611 and 1614.

Matchut/Matchot was Powhatan's last capital, after moving from Werowocomoco and then Orapaks

Source: Library of Congress, Novi Belgii Nov que Angli (by Nicolaes Visscher, 1685)

Matchut was located on the northern bank of the Pamunkey, upstream of the modern Route 360 highway crossing. From there canoes could easily travel downstream on the Pamunkey River, but the English sailing ships going upstream would be caught in a narrow channel and would be vulnerable to a land-based attack.

Locating Matchut on the northern bank of the Pamunkey put another water barrier between the capital of the Algonquians and the English, providing some protection against a ground attack. The new capital was at the edge of Monacan territory, but the threat of the English caused the two groups to become allies by 1611. The alliance with the Monacan, and the greater distance from the English at Jamestown, made Matchut a safer location than Orapakes.1

Compared to the swamps at Orapakes, the new location also offered better water access for Powhatan to receive corn provided by his subordinate werowances. The flood plain provided more farmland for local production of corn, beans, and squash.

Matchut was far enough away from the English for Powhatan to feel more secure. Captain Ratcliffe had brought an English ship up the Chickahominy River to Powhatan's "seat" at Orapakes in 1609. The visit was a disaster for the colonists, and 34 of the 50 men on the ship were killed.

Ratcliffe personally was captured and tied to a stake and tortured to death, as his flesh was slowly sliced off and tossed into a fire. The defeat at Oropakes must have intimidated the colonists who managed to flee on their ship back to Jamestown, but Powhatan was also affected by the realization that a ship could get to Orapakes.

Pocahontas lived with Powhatan at Matchut. When he dispatched his daughter to visit the Patawomeck in 1613, she walked from Matchut to the edge of the Potomac River. The 60-mile trip required crossing the Rappahannock River, which she probably did in a canoe paddled by the men who accompanied her on the trip.

John Smith's map provides a clue that Pocahontas was crossing the edge of Tsenacommacah, the territory under Powhatan's control. Towns were clustered on the north edge of the river, suggesting it was a boundary or provided a barrier between the residents and Powhatan.

Pocahontas crossed the Rappahannock River (blue line) into territory that may have been less obedient to Powhatan, who was based in Matchut in 1609

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

At Patawomeck, Pocahontas was betrayed by the Patawomeck chief Japazaws. Instead of treating her as the emissary of a leader to whom he owed allegiance, Japazaws helped Captain Samuel Argall kidnap Pocahontas and carry her away to Jamestown. Pocahontas was moved to Henricus, and would not see Matchut again until March, 1614.

in foreground: capture of Pocahontas (1613),

in background: Dale's destruction on the trip to Matchut while trying to return her (1614)

Source: Theodore De Bry Copper Plate Engravings

Matchut may have been safer than Powhatan's last two capitals, but it was on a river and still accessible to the English. In 1614 Ralph Hamor visited Powhatan to propose a marriage between Sir Thomas Dale, the governor of the colony, and one of Powhatan's daughters. Sir Thomas Dale was already married, but hoped a marriage between a daughter of Powhatan and the leader of the English would bring an end to warfare between the Powhatan tribes and the English.

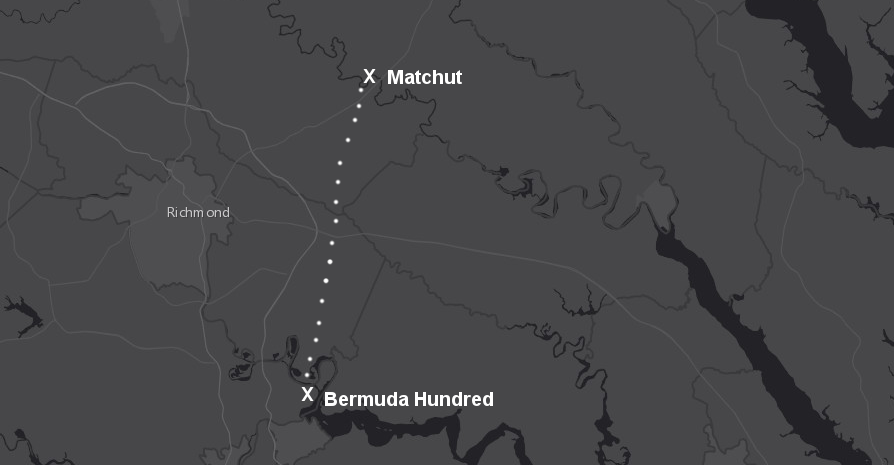

Hamor reported that Matchut was a two-day hike from Bermuda Hundred on the James River to Matchut at the "head" of the Pamunkey River. He noted that Matchut was on the north bank, keeping "the main river betweene him and us, least at any time we should martch by land unto him undiscovered." Hamor judged Matchut was "some three score miles distant from us."2

He overstated the distance. By land, Matchut is about 30 miles away from Bermuda Hundred and Henricus, where Pocahontas was held in captivity. Powhatan probably had a better sense of the distance between his third capital and the English, and understood the security risks more clearly.

Matchut was 30 miles away from Bermuda Hundred

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Powhatan rejected Sir Thomas Dale's proposal of marriage, claiming his daughter was already committed to another man. Hamor's report suggests Powhatan was tired of the fighting and was considering moving even further away from the English:3

Dale then tried to pressure Powhatan by bringing Pocahontas to Matchut, and sailed with 150 men up the Pamunkey River.. Dale hoped to exchange Pocahontas in return for the settlers that had fled to the Algonquian towns, and for the English tools and weapons they had stolen.

According to Hamor's account (obviously written from the English point of view, with phrases such as "justly provoked"):4

Pocahontas got off the English ship and met with two of her half-brothers. She was upset that her father Powhatan was unwilling to meet the terms established by the English to ransom her, but also said she planned to stay with the English and to marry John Rolfe. The decision may have been affected by her quick adaptation to the colonial culture and her recognition that she could obtain higher status by "switching sides." She returned to Henricus, married Rolfe in the church at Jamestown, and never saw Matchut again.5

Powhatan agreed to let Pocahontas marry John Rolfe and to live in peace with the English, ending the first Anglo-Powhatan War. Powhatan never saw his daughter again, and never agreed to any other marriage between a Native American and an English colonist.

All of Tsenacommacah was in Tidewater, and land-based sorties from English sailing ships were a threat to all of Powhatan's capitals. Opitchapam and Opechancanough, who led the paramount chiefdom after Powhatan died around 1618, had the same problem. Matchut was further away from Jamestown than Powhatan's other "seats," but no location in Tsenacommacah was far enough away to prevent a deadly English raid.

As the English expanded control over Tidewater, Matchut and almost all other Native American towns ended up within territory controlled by colonists. It is possible that Matchut/Matchot was located further downstream on the Pamunkey River, at a site that was granted to granted to William Bassett in 1647. Bassett named his plantation "Eltham," and it remained in his family for centuries. In 2024, the owner of Eltham Farm granted a conservation easement on his 310 acres to the Capital Region Land Conservancy, which said:5