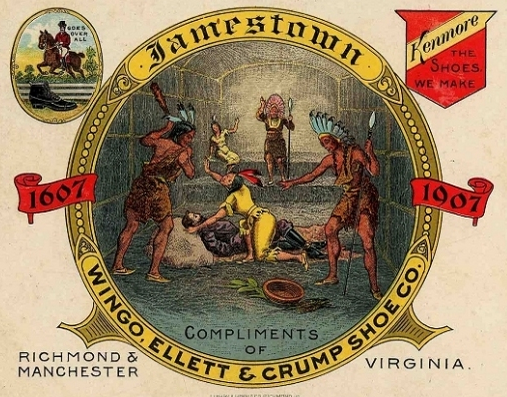

the myth of a love relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith has persisted despite all evidence to the contrary

Source: Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Pocahontas and Smith (1907 postcard)

the myth of a love relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith has persisted despite all evidence to the contrary

Source: Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Pocahontas and Smith (1907 postcard)

Pocahontas was the daughter of Wahunsenacawh (Wahunsenacock/Wahunseneca), the paramount chief known to the English as Powhatan. She was born around 1596. Her formal name was Amonute, but she was most often called Matoaka.

Pocahontas, apparently the Algonquian word for "playful" or even "brat," was a pet name for her. She was raised by her mother initially in her mother's town, and may have been one of 100 children fathered by Wahunsenacawh.

According to Mattaponi oral history, she was a member of that tribe and married a local man named Kocoum sometime after 1609. The Secretary of the colony, William Strachey, also recorded that marriage. When Matoaka converted to Christianity and married John Rolfe, she took the name Rebecca.1

In the 1995 movie Pocahontas, Disney repeated the inaccurate myth of Pocahontas and John Smith falling in love in 1608. Smith had wandered too far up the Chickahominy River and been captured by a group that was out hunting deer. According to the myth, Smith was brought to Powhatan, and Pocahontas bravely challenged her father in order to save John Smith from execution. In the process, she tossed aside her love for Kocoum in exchange for a new relationship with the English captive.

The Disney movie does illuminate how both the Native Americans and the English viewed the other side as "savages," but the portrayal of Pocahontas ignores some key facts in order to enhance the story line. Most obviously, John Smith was not clean shaven and his hair was not blonde. In 1608, he was 25-26 years old and Pocahontas was just 10-11 years old. She was a child rather than a mature young woman, so any relationship could not have been a love between consenting adults.

Smith never claimed Pocahontas saved his life in dramatic fashion until 1624, when everyone who might challenge the story was dead. He finally wrote, 16 years after the supposed rescue, how Pocahontas had stopped an execution in front of her father:2

Disney portrayed Pocahontas as a heroine who saved John Smith from getting his head smashed with clubs

Source: YouTube, Pocahontas - Savages (Part 2)

That tale is subject to multiple interpretations. The Disney movie offers a sanitized version of the harsh, conflict-ridden interaction between Native Americans and English colonists settling in Virginia. Smith's capture by a group of Native American hunters on the Chickahominy River was not bloodless; his two companions that went with him in a canoe upstream of the town of Apocant were killed.3

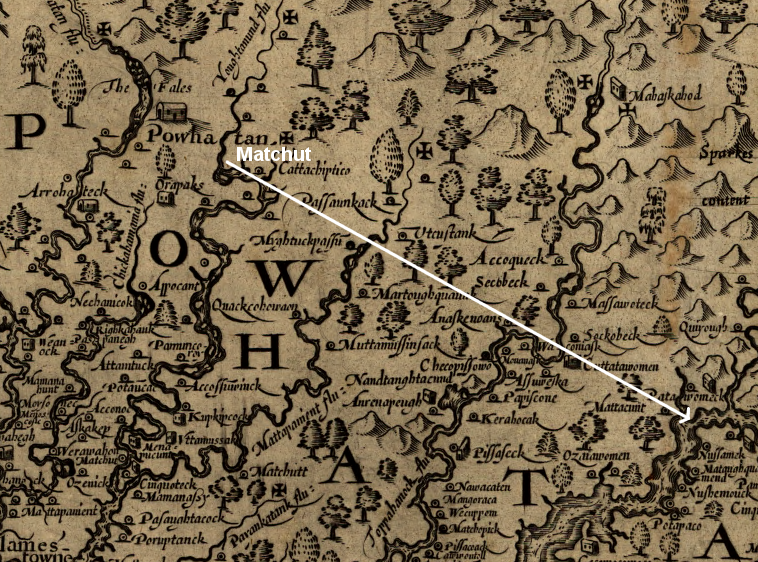

John Smith was captured after he canoed up the Chickahominy River past Appocant

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

History makes clear that the relationship between colonists and Native Americans was rarely harmonious; everyone did not live "happily ever after." Less than 30 years after arriving in Virginia, Native Americans were expelled from the area around Jamestown and the English colonists constructed a wall on the Peninsula. By the end of the 1600's, the Native American culture east of the Fall Line had been thoroughly disrupted.

Some choose to the rescue myth in a positive light. In the 1995 movie, Pocahontas was "the first truly empowered Disney heroine." The story can be interpreted as valorizing a woman of color, defining a strong woman who chooses her own path rather than subordinating her desires to satisfy the men in her life.4

The rescue story could reflect an actual event. Perhaps the threat to his life was real, and Pocahontas did spur her father to spare the Englishman's life.

John Smith claimed Pocahontas rescued him from execution by Powhatan, and various myths have elaborated on that claim ever since

Source: Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Pocahontas and Smith (1907 postcard)

Perhaps Smith misjudged what had happened. In 1607, the Native Americans recognized Smith was a man of importance in the English community. He may have been subjected to a ritual that involved laying his head on a block and pretending to prepare to smash his skull, then allowing him to be "reborn" into the tribe. Powhatan may arranged a ceremony that Smith did not understand was an adoption, establishing the English settlement as one more of Powhatan's tributary tribes.5

the supposed rescue, as portrayed in the writings of John Smith in 1624

Source: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles

He could have embroidered a real event in his 1624 version, or created it completely out of thin air. The intersection between history and fantasy in this case will always be fuzzy, providing an opportunity for creative writers and artists to reshape the story to fit current times.

Smith was a strong leader with a domineering personality, a bold adventurer with an extra-large ego. His fellow colonists objected to his decisions as president of the council at Jamestown, and sailed back to England in late 1609. He had been seriously injured when his powder bag exploded, and survived what may have been an assassination attempt.

He left Virginia less than two years after the supposed rescue by Pocahontas. He was wounded, and his rivals on the Council had him displaced from his job as the Virginia Company's top official in the colony.

Pocahontas later complained that Smith did not notify her that he was leaving Virginia. If he had been formally "adopted" as a son by Wahunsenacawh/Powhatan and she had played a key part in the ceremony, then leaving without notice would have been excessively rude.

From the English perspective, it would have been a security risk to alert Powhatan about the change in leadership at Jamestown. Powhatan did alter his behavior towards the colonists after Smith left. He ambushed a trading party that came to Orapax for corn, killing over thirty, and initiated a war of attrition that lasted until 1614.6

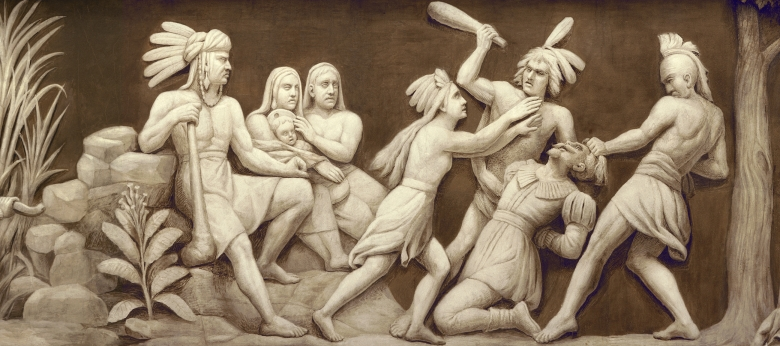

the myth of Pocahontas rescuing Captain John Smith from execution by Powhatan is commemorated in art installed in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Constantino Brumidi's "Frieze of American History"

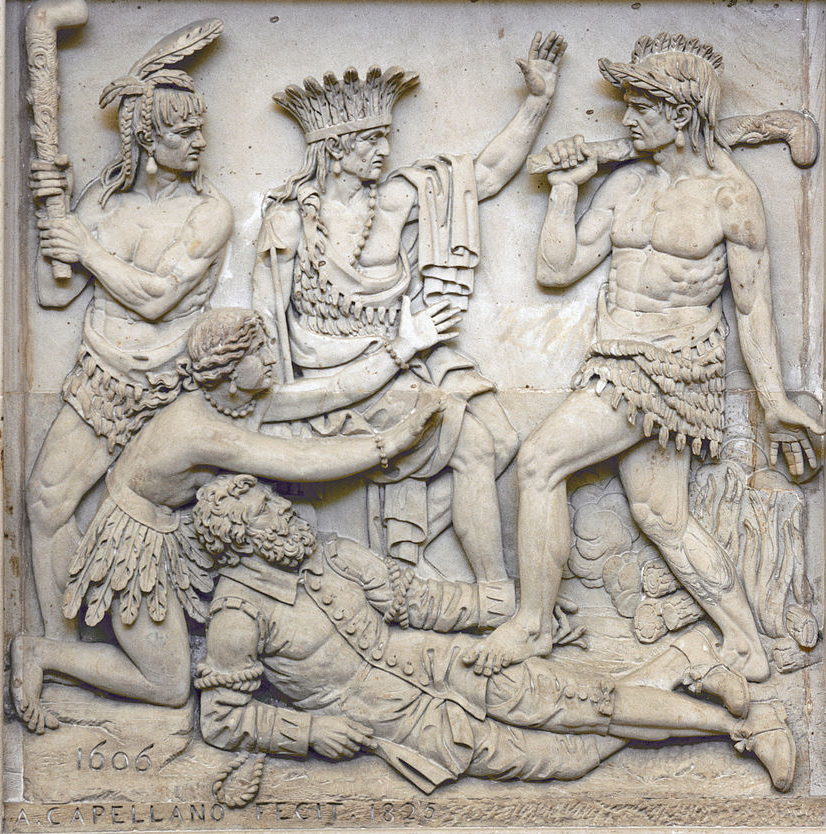

Antonio Capellano's "Preservation of Captain Smith by Pocahontas, 1606" also represents the Pocahontas rescue myth in the US Capitol

Source: Flickr, Architect of the Capitol

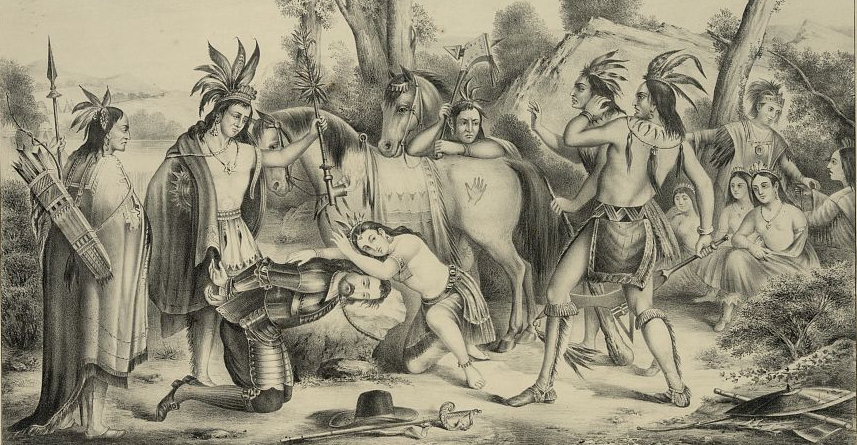

an 1870's lithograph of the mythical rescue was fanciful enough to include horses, rock outcrops, and mountains that reflected the more-recent experiences with tribes west of the Mississippi River

Source: Library of Congress, Smith rescued by Pocahontas

Pocahontas ended up as a key player in ending the First Anglo-Powhatan War, establishing peace between the Powhatans and the English. According to the Mattaponi tradition, her mother was a Mattaponi woman, and her older sister (not a child of Wahunsenacawh/Powhatan) was named Mattachanna.

In 1613 Pocahontas was about 16 years old. The Mattaponi describer her as living with the Patawomeck then. She was married to Kocoum, who was the younger brother of the Patawomeck weroance named Japasaws. Pocahontas was also a mother, having birthed a son of Kocoum's.7

According to another interpretation of events, Powhatan's daughter left Powhatan's third capital at Matchut in 1613 to visit the Patawomeck. She walked 60 miles to the mouth of Potomac Creek, on what today is known as Marlborough Neck. She may have been acting as a trader and as an ambassador for her father.

Pocahontas walked from Matchut to the town of the Patawomeck in 1613, and returned by ship in 1614 to tell her brothers that she planned to marry John Rolfe

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

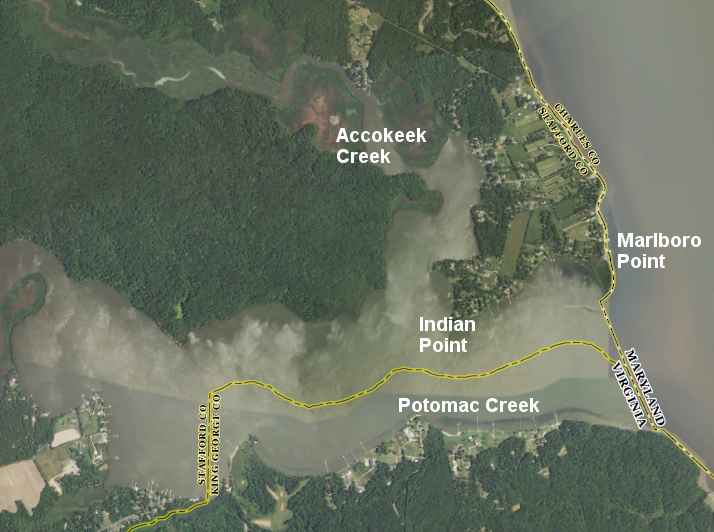

On that peninsula, the Patawomeck could take advantage of the fresh water of Accokeek Creek and the oysters in the brackish Potomac River. The location of their main town was surrounded on three sides of water, which offered some protection against attack. The neighbors were not always friends, and life was not always peaceful.

Archaeologists excavating the first two sites documented in Stafford County, ST1 and ST2, determined that the Patawomeck's town was protected by a wooden palisade. The pattern of circles of darker earth in the ground, caused by the decay of the organic wood in otherwise-light sand and clay soil, revealed where that postholes were lined up in a row to form a wooden wall.8

Marlboro Point is at the confluence of Potomac Creek/Potomac River

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Passapatanzy 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)

A substantial amount of labor was required to build such a palisade. The Patawomeck had no draft animals, so they had to drag the wood by hand to their town site. Digging holes for the wooden wall required using tools made with shoulder bones of large animals, which were far less efficient than the iron shovels used by the English to build their palisade at Jamestown. The romantic idea of "noble savages" living in peace and harmony in Pocahontas's childhood, before the arrival of the English, is far from the reality of pre-colonial Virginia. Threats from rivals forced Native Americans to fortify their towns.

If traveling to the mouth of Potomac Creek as a representative of her father, Pocahontas might have reminded the Patawomeck that Powhatan considered them to have an obligation to pay tribute. The Patawomeck were associated with Powhatan, but perhaps not fully obedient.

Powhatan's control of over 30 tribes was centered on the York River, and he was still expanding his power over adjacent tribes when the English sailed up what he called "Powhatan's River." When the English arrived in 1607, the Chickahominy tribe near the core of his influence was still independent. The tribe even allied with the English in 1614. The Chickahominy waited until 1644 to join the paramount confederacy under Powhatan's successor, Opechancanough, after the threat from Jamestown became too great and he was makinh arrangements for a second great uprising.9

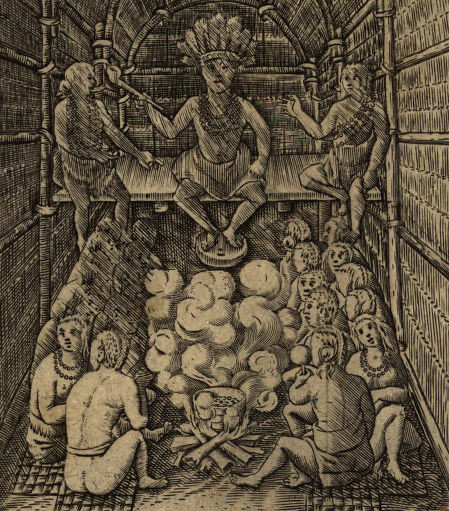

Powhatan, as seen by John Smith at Werowocomoco

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606

Not surprisingly, Powhatan's influence was weak on the perimeter of his territory. The Patawomeck had previous disobeyed his orders not to sell corn to the English when Powhatan was trying to starve the colony at Jamestown. The weak allegiance of the periphery tribes was demonstrated most clearly in 1613 when Pocahontas was visiting Japasaws, chief of the Patawomeck.

Instead of committing to pay tribute to the paramount chief, Japasaws cut a deal with an English ship captain, Captain Samuel Argall, who was at the town seeking to buy more corn. Japasaws' wife pretended to be anxious to go on board Argall's ship, but Japasaws refused permission unless she was accompanied by another woman. Pocahontas agreed to accompany her. They all ate a meal with the English ship captain, during which Japasaws kept tapping on Argall's foot underneath the table as a reminder that they had a bargain.

Captain Argall let Japasaws and his wife return to the shore, and gave them a copper kettle as a reward for their assistance in the kidnapping of Powhatan's daughter. He kept Pocahontas as a prisoner, and transported her and his shipload of corn back to Jamestown. The Mattaponi believe Kocoum was murdered by the English at this time but their son survived, to be raised among the Mattaponi. Tradition holds that his descendants include the famous entertainer Wayne Newton.

how Pocahontas may have spoken to Sir Thomas Gates after arriving in Jamestown, complaining about Captain Argall (behind her)

Source: Virginia Museum of History and Culture, the Abduction of Pocahontas

The English hoped to exchange Pocahontas for eight men held as prisoners by Powhatan, plus the weapons he had captured. Three months after being notified of her capture, Powhatan returned seven men but retained the weapons. The English then refused to release Pocahontas. She was transported upstream to Sir Thomas Dale's settlement (the "Citie of Henricus") on the south bank of the James River.

Reverend Alexander Whitaker was give the responsibility for her getting trained in English customs and Christian practices. As a man, Whitaker's ability to deal with her personal habits was constrained. English women in the colony must have been recruited to teach her how to bath with English soaps, how to dress, and how to behave as English men desired.

She would have experienced different patterns of living, from sleeping on beds to eating meals at scheduled times. Her clothing would have been transformed. Dressing in the English clothing was most likely uncomfortable and unusually restrictive of movement. She would have eaten different foods, including dairy products when she may have been lactose intolerant. How she washed and stayed clean would have involved practices that were foreign to Pocahontas.

Rev. Whitaker trained her in Christianity, probably imposing his Anglican beliefs through repetition as well as persuasion. He would have prohibited her from performing any of her traditional rituals viewed as "pagan."

John Rolfe got to know her at Henricus after July 1613. How his relationship with Pocahontas evolved is unknown, but he was a widow in an isolated colony with almost no available English women and a teen-age Pocahontas must have been lonely for companionship. Her marriage to Keocum would not have been viewed as an impediment. That marriage was treated as irrelevant because no Christian rites had been performed.

The English recorded no other interracial marriages, but Spanish spies reported that 50 of the men had Native American wives. Archeological evidence shows Native Americans living in Jamestown Fort in the early years.

In 1614, Sir Thomas Dale put Pocahontas onto a ship and sailed up the Pamunkey River to Powhatan's capital at Matchut in hopes of collecting a ransom. The shoreline of the Pamunkey River was lined with warriors shouting at the ship:10

The 150 English traveling upstream burnt houses and killed a few of Powhatan's warriors on the journey, but the Native Americans chose to negotiate for the release of Pocahontas rather than to fight. The English who reached Matchut never saw Wahunsenacawh/Powhatan in person, but negotiated instead with his younger brother Opechancanough. The English allowed Pocahontas to go onshore, where she visited with two half-brothers who confirmed she was in good shape.

Though the English were willing to release Pocahontas, no deal was struck. Perhaps Opechancanough was unwilling to return captured weapons, or the amount of corn he offered in exchange for Powhatan's daughter (his niece) was too low.

Pocahontas did not try to escape her captors, and appears to have been a willing hostage at the time. Reportedly she was visited by her older sister Mattachanna and her husband Uttamattamakin. She may have been experiencing "Stockholm syndrome," where captives cope with their situation by identifying with the people who seized them, but she may have calculated already that becoming part of English society was to her personal advantage.

Though Pocahontas was captured by force and carried to Jamestown and Henricus involuntarily, at some point she did choose to become a part of the society of English colonists. That may have been a calculated decision, based on her ability to think creatively. She had been a free-wheeling "brat" as a child, but as an adult could have assessed carefully in which culture she might have the greatest influence.

As a member of the Algonquian world, she was just one of many children fathered by Powhatan. She may have been his favorite mischievous child at one point in his life, but as an adult she would have little status.

In English society, she was given special respect closer to a princess than to a commoner. As the daughter of Powhatan and the wife of John Rolfe, she may have anticipated she could enjoy a better life in the English culture. She would face discrimination by the English because she was a woman and a Native American, but there is no documentation that she tried to escape from Henricus to a town controlled by her father Powhatan.

Pocahontas officially converted to Christianity and got baptized. She and John Rolfe were married on April 5, 1614. Powhatan sent two of his sons and his brother Opachisco to the wedding. Rolfe's enthusiasm for his second marriage may have been lukewarm. The interracial aspect was probably just a minor factor, if an issue at all; by 1614, "Rebbecca" was dressing in English clothing and was trained to behave like a cultured English woman. It is likely that a colony filled with young men had already discovered that physical relationships with Native American women was better than celibacy.

John Rolfe married Pocahontas/Rebbecca only after her baptism, establishing the precedent for official recognition of interracial unions in the colony. He justified the marriage as:11

1840 painting installed in US Capitol imagining the 1614 baptism of Pocahontas

(Powhatan's brother Opachisco is portrayed in shadow, seated and refusing to watch ceremony)

Source: Architect of the Capitol

Pocahontas' decision to stay with her captors was used as an excuse by both Powhatan and the English colonists to establish a truce:12

The "Peace of Pocahontas" lasted until 1622. Native Americans could plan on harvesting the crops they planted, rather than witness colonists destroy their agricultural fields when the corn was ripe. The Virginia Company could recruit more people willing to cross the Atlantic Ocean and work as indentured servants, enhancing company profits.

Disney inaccurately portrayed Pocahontas and John Smith as lovers, when in real life she married John Rolfe

Source: Disney Entertainment, Pocahontas Photo Gallery

Ralph Hamor reported that he visited Powhatan in 1614. According to Hamor, Powhatan asked him about his daughter, and he was pleased that she was happy in her adopted culture:13

After marrying John Rolfe in 1614, Pocahontas was known in the English colony as Rebecca Rolfe. She gave birth to a son known as Thomas Rolfe in 1615. One claim of a Mattaponi leader, Dr. Linwood Custalow, is that the child was not Rolfe's. Supposedly Pocahontas was pregnant when she was married, due to an earlier rape by an Englishman. Since she was under the control of Reverend Alexander Whitaker, the opportunity to commit such an act would have been limited to just the top leaders in the colony or the minister himself. The claim is that Sir Thomas Dale was responsible.

The most suspicious aspect of the birth is that it was never officially recorded. The Anglican colonists were clearly aware of the importance of documenting Christian births and tracing future inheritance rights. Such an event would have been extremely significant in the cultural relationship between the colony and the Native Americans who surrounded it, particularly if it could lead to a long peace.

The birth date should have been documented in reports to the directors in London, but no one in the colony chose to write it down in any record still remaining. The absence of a birth date for Thomas Rolfe leaves open the possibility that the marriage was a cover-up for a rape, and Rebecca Rolfe's pregnancy had not lasted nine months after the marriage.

The English tradition is that the child was named after Sir Thomas Dale, who was at the time John Rolfe's superior and top leader in the colony.14

In 1616 Pocahontas/Rebecca Rolfe, John Rolfe, and their son Thomas Rolfe traveled to London together with Powhatan's advisor Uttamatomakkin (Tomocomo), his wife Matachanna, and other Native Americans.

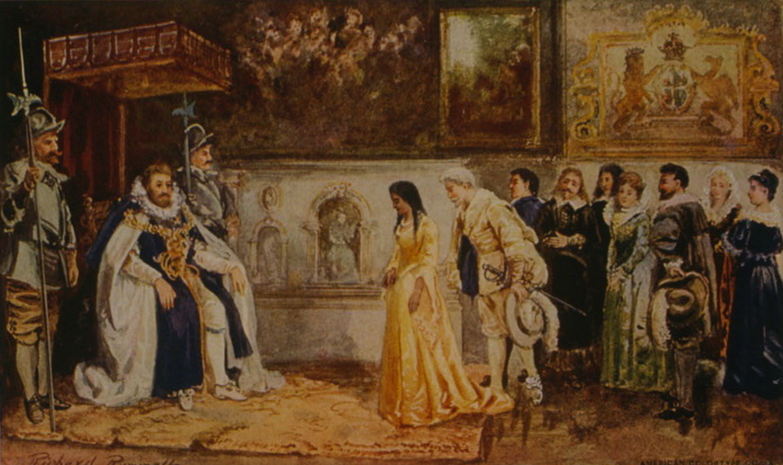

The Virginia Company used them all in a marketing campaign to generate interest and funding for their investment in the colony. She was advertised as a royal princess and drew public attention during her nine months in England. The company managed to get Pocahontas/Rebecca Rolfe into the audience of a pageant held by King James at Whitehall Palace.

as part of a marketing/recruiting effort, the Virginia Company wanted to get Pocahontas introduced as Virginia royalty to King James in London

Source: Library of Congress, Pocahontas at the court of King James

The king's appearance at the pageant was not impressive enough for Uttamatomakkin (Tomocomo) to recognize that the man was England's top leader. Uttamatomakkin complained that the Native American delegation was not granted sufficient respect during the visit, and ended up embittered at the English.15

the Banqueting Hall of Whitehall Palace, where Pocahontas attended a play and saw King James I, is near the home of Great Britain's Prime Minister at 10 Downing Street

The Virginia Company initially housed the group at a low-cost inn, La Belle Sauvage on Ludgate Hill in the center of busy London. After three months, everyone was moved west to the suburb at Brentford. George Percy's family lived in the area, and the Virginia Company may have found that connection to be useful.

Brentford was more rural, and must have been more comfortable for the Native Americans. Until reaching London with its 200,000 residents, they had never been in a place with more than 1,000 people. The largest population center they had seen was Werowocomoco.

The atmosphere in Native American towns in Virginia may have been filled with smoke, but the sulfurous smoke from burning coal on Ludgate Hill would have been an unfamiliar and perhaps unpleasant smell. The noise from the horse-pulled carts on paved streets in London, and the stench of the horse dung and sewage on those streets, would have been completely foreign experience during the three months spent in crowded downtown London.

The move from La Belle Sauvage to Brentford made it more difficult to display the Native Americans to potential investors and supporters of the Virginia Company. The shift may have been a necessary morale-building change, and an attempt to maintain the health of the Native Americans.16

The Virginia Company sent the Rolfe family and Uttamatomakkin back to Virginia after nine months. By that time, both Rebecca Rolfe/Pocahontas and her son Thomas were sick. She may have contracted dysentery or tuberculosis.

Soon after the ship started to sail down the Thames River from London, Pocahontas and her child were too sick to continue. They were taken off the ship at Gravesend, on the southern bank of the Thames River just downstream from Greenwich. When she died on March 21, 1617, she was 22 years old. John Rolfe arranged for his ailing son Thomas to remain in England in the care of a relative, after Pocahontas was buried at Gravesend.

John Rolfe himself returned to Virginia, where he married for the third time and then died in 1622. The circumstances of his death were not documented - just like his marriage. He may have died from illness just before the major uprising orchestrated by Opechancanough.17

Rebecca Rolfe/Pocahontas stayed first at La Belle Sauvage on Ludgate Hill (1) and then in Brentford (2), but died at Gravesend (3) after starting the trip home to Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Thomas Rolfe finally made it back to Virginia, the home of his mother, when he was 20 years old. His parents and his grandfather Powhatan were dead by then, but through them he inherited thousands of acres of land. The site of his birth, the Varina plantation, was part of that inheritance.

Thomas Rolfe married an English colonist, Jane Poythress. With permission of colonial officials, he met his uncle Opechancanough sometime between 1641 and the 1644 uprising. After the uprising, Thomas Rolfe joined the colonial militia and prepared to fight against his Native American relatives. Like his mother Pocahontas, Thomas Rolfe chose to be a member of English society.

His one child, a daughter named Jane Rolfe, was born around 1650. After marrying Colonel Robert Bolling in 1675, she had a son named John Bolling. That great-grandson of Pocahontas, the great-great-grandson of Powhatan, had seven children.18

the portrait of Pocahontas that hung at Booton Hall, the ancestral home of John Rolfe, shows her with Europeanized features such as brown hair and light skin

Source: US Senate, Pocahontas

Many members of the "First Families of Virginia" (FFV's) trace their ancestry back to Pocahontas through John Bolling. That link limited the ability of segregationists in the 1920's to identity a pure-white Virginia race, while defining everyone else as Negro and restricting their civil rights, social mobility, and economic opportunity through Jim Crow laws.

The 1924 Racial Integrity Act facilitated discrimination, as state officials sought to identify everyone with one drop of Negro blood and to recategorize remaining Native Americans in Virginia as "blacks" - but the FFV's related to Pocahontas ensured that the definition of white allowed for one drop of Native American blood.

Edith Bolling Wilson, wife of President Wilson and a native of Wytheville, Virginia, was especially vocal about her ancestral link to Pocahontas, nine generations earlier. Her ancestry was traced back through the first marriage of Robert Bolling to Pocahontas' granddaughter, Jane Rolfe (and 511 other ninth-generation ancestors). Such descendants were described as "Red Bollings." That was in contrast to the descendants of Robert Bolling and his second, white wife, who were known as "White Bollings."19

three centuries after the marriage of Pocahontas to John Rolfe, their descendants affected the implementation of the 1924 Racial Integrity Act

Source: Library of Congress, The wedding of Pocahontas with John Rolfe

Edith Galt highlighted her connection to Pocahontas, allowing a person born in Wytheville to create a connection to royalty

Source: "Chronicling America," Library of Congress, Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 24, 1915 (Image 43)

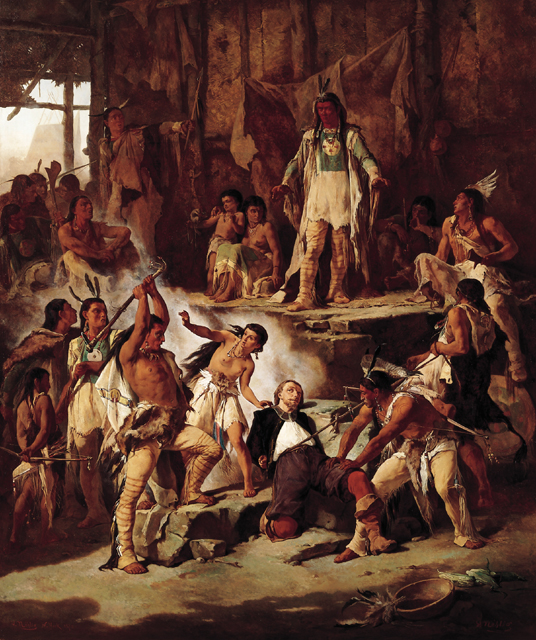

in this 1870 painting of Pocahontas saving John Smith and the colony, Powhatan (looking down from platform) and other Native Americans are dressed in the style of Plains Indians

Source: Brigham Young University, Pocahontas and John Smith (by Victor Nehlig, 1870)

long before Disney made movies, American writers imagined Pocahontas as a child of nature

Source: Elmer Boyd Smith, The Story of Pocahontas and Captain John Smith (1906)

in 1906 when Virginia was passing laws to segregate the races, Pocahontas was portrayed as a light-skinned princess

Source: Anna Cunningham Cole, The Jamestown Princess (1907)

in contrast, Elmer Boyd Smith portrayed Pocahontas as a dark-skinned bride in 1906

Source: Elmer Boyd Smith, The Story of Pocahontas and Captain John Smith (1906)