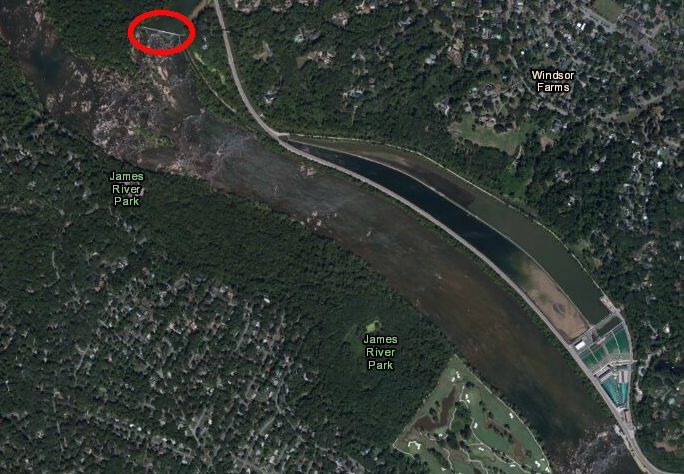

Richmond's raw water intake on the James River is at a diversion dam on the downstream end of Williams Island

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

Richmond's raw water intake on the James River is at a diversion dam on the downstream end of Williams Island

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

The Algonkian-speaking tribe that lived at the Fall Line of the James River in 1607 relied upon springs to provide drinking water. The first Europeans to settle the site, which was chartered as the City of Richmond in 1737, also drilled wells to supply individual houses.

Today, some residents still fill up jugs at springs in public parks, but Richmond relies upon the James River as its source of raw water. A dam at Williams Island diverts river water to settling basins near Byrd Park, which then supply the drinking water treatment plant.

The city's drinking water system has evolved over many years. Richmond was the first city in the United States to build a sand filter to clean its drinking water. The wells within the city were growing contaminated, so in 1830 Richmond decided to draw fresh water from the James River. At the time, only 44 cities in the US distributed public drinking water; everywhere else, customers had to draw water from wells.1

The city recruited a German-trained engineer named Albert Stein, who had just created a drinking water system for Lynchburg. Stein designed a standard system to pump water from the James River to the new Marshall Reservoir 160 feet above river level. From the reservoir, gravity distributed the water through pipes.

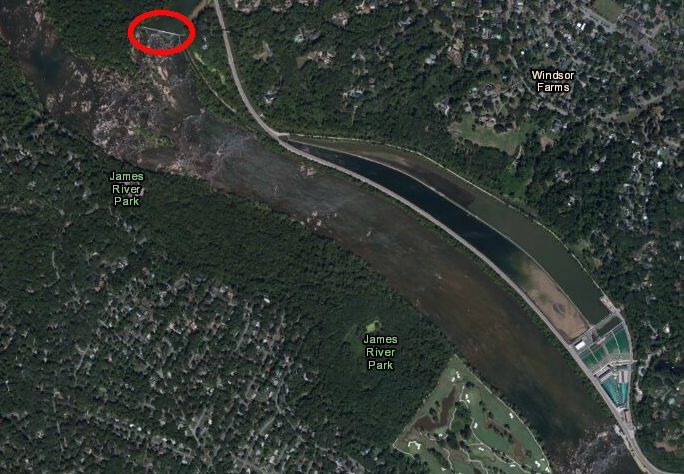

the Marshall Reservoir was west of Hollywood Cemetery and the developed area in Richmond - initially

Source: Illustrated London News, Richmond, Virginia, the Capital of the Confederate States of America (September 7, 1861); National Archives, Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay: Sheet No. 13 Richmond; Virginia Commonwealth University, Baist Atlas in Richmond, VA (1889)

the waterworks at Clarke's Spring relied upon water pumped from the James River, then distributed by gravity

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Richmond, Virginia

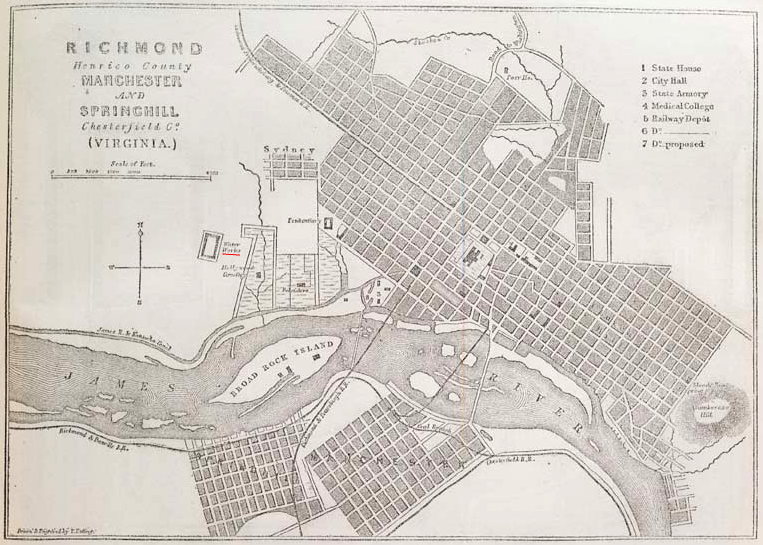

red X marks location of the old Marshall Reservoir - now Clarke Springs Elementary School

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

The unusual element was his creation of a filtration system. The project was intended to filter out the mud from the river water, improving the taste and smell of the city's water. (It was not until 1854, after the London cholera epidemic, that scientists recognized clean-looking water could harbor unhealthy bacteria and viruses.)

Stein's filtration design required raw water to be pumped upwards through a bed of gravel, then through a top layer of sand. Larger particles were trapped in the gravel; smaller particles were trapped in the sand. Purging the particles from the filter required using water flowing in the other direction, draining down through the sand and gravel and flushing everything into a waste outlet.2

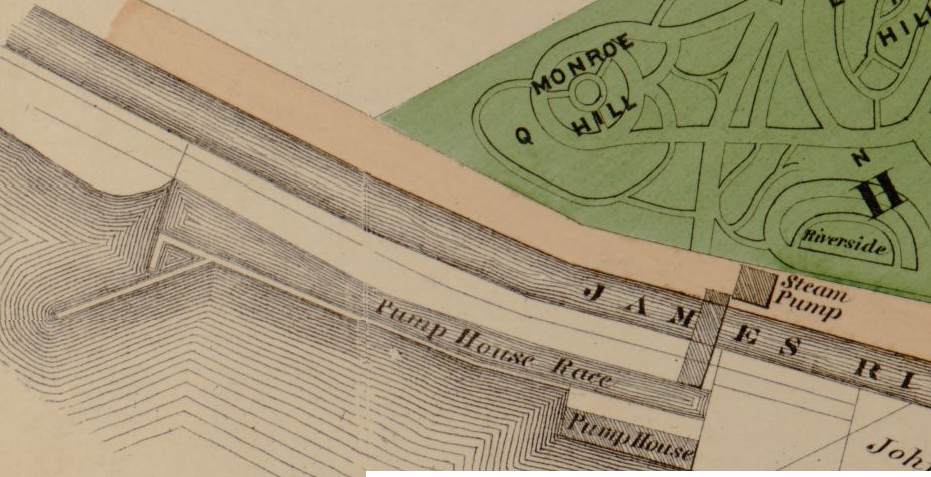

the pump to lift James River water to the Marshall Reservoir was located just upstream of the modern Lee Bridge near where President Monroe was buried in Hollywood Cemetery

Source: Library of Congress, Illustrated atlas of the city of Richmond, Va. (1877)

The filter system was abandoned after just a few years, but the Marshall Reservoir (on the site of today's Clarke Springs Elementary School) survived until 1934.3

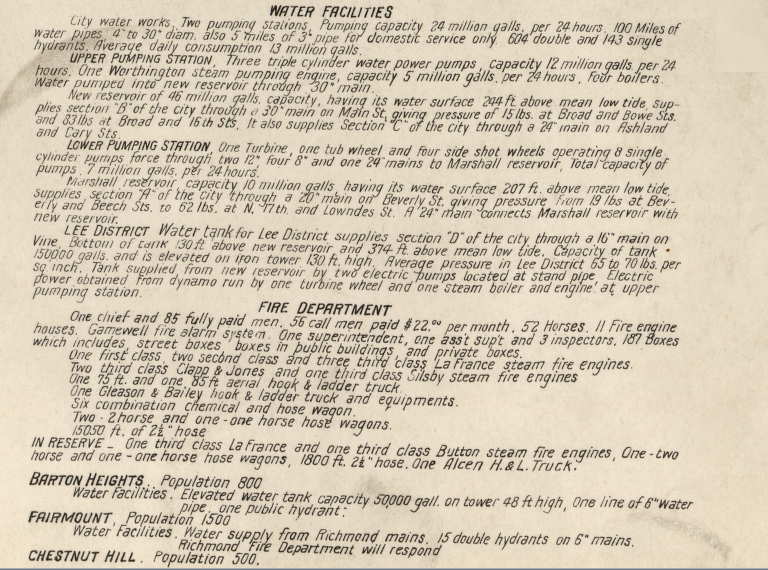

In the 1870's, Richmond expanded its water system by building the "New Reservoir" a mile west of the Marshall Reservoir, moving the raw water intake upstream, and designing New Reservoir Park (renamed Byrd Park in 1906) to surround the new reservoir. A granite Pump House was completed on the bank on the James River and Kanawha Canal in 1883, followed by two narrow settling basins. The Pump House lifted water up to the New Reservoir until 1924, and the Pump House Pavilion provided a social setting for many parties.

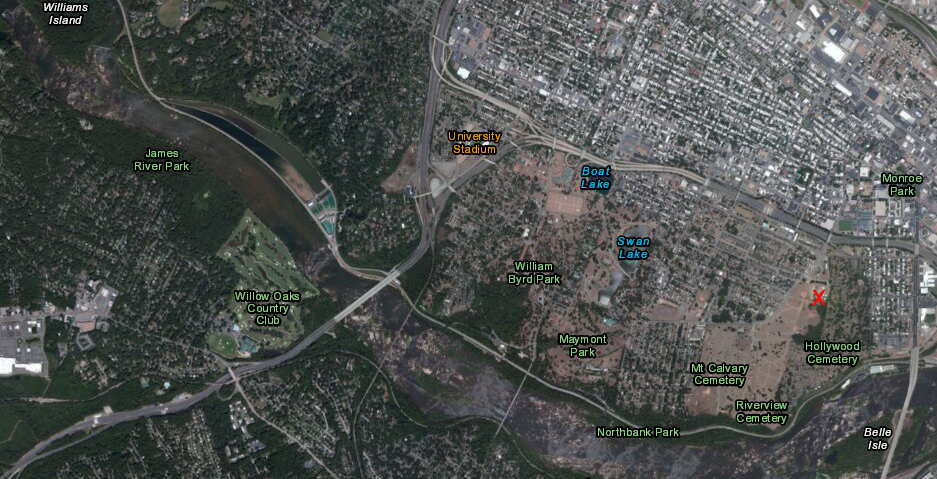

in the 1870's, the new reservoir in what became Byrd Park replaced the Marshall Reservoir

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University, Baist Atlas in Richmond, VA (1889)

The city built Williams Dam in 1905, increasing the supply of water even in drought years. Chlorination started in 1913.4

Richmond's New Reservoir was located in Byrd Park, west of the Marshall Reservoir and at a higher elevation

Source: Library of Congress, Illustrated atlas of the city of Richmond, Va. (1877)

A 1917 report indicated the settling basins had not been cleaned out since originally constructed. Silt had filled up 1/3 of the storage capacity, and the city was considering shifting the intake to draw water from behind Bosher's Dam further upstream.

At the time, the treatment process consisted of letting solids settle, using alum at times to coagulate them, then adding chlorine. The process did not produce uncontaminated drinking water. The 1917 report stated simply:5

Water was pumped from the treatment plant (at river level) to supply the west end of the city - the "high" level of elevation - from a standpipe at Byrd Park. The "intermediate" level, which included most of the city, was supplied from larger reservoirs also located at Byrd Park. Water flowed down from the Byrd Park reservoirs to the old Marshall Reservoir next to Hollywood Cemetery, to suppky "manufacturing and low class, congested residential districts, and a part of South Richmond."6

the Sanborn Insurance Company documented Richmond's water system in 1905

Source: Library of Congress, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Richmond, Independent Cities, Virginia (1905)

In all regions, water pressure to fire hydrants was inadequate to supply more than one engine. As the report noted:7

The Pump House and William Island/Williams Dam are now part of James River Park. Richmond's Department of Public Works focuses on water supply and distribution, while the recreational opportunities in the city are managed by a separate part of the city government.8

the Byrd Park Pump House was designed with a large pavilion, to provide recreational as well as utility services

Source: Library of Congress, General View Of Pumphouse From NORTH - James River & Kanawha Canal, Pumphouse

That assessment triggered an upgrade of the waterworks. When a new water treatment plant was completed at its current location in 1924, the city finally was able to filter its drinking water before distribution. Over time, that facility was expanded to supply 60 million gallons/day (MGD) of drinking water.

Another water treatment plant was built at the site in 1950. That second facility now can supply 70 million gallons per day. Though the rated capacity is 132 million gallons per day, in 2025 Richmond's water treatment plants typically produced 100 million gallons/day in the summer and 50-75 million gallons/day in the winter.

Source: Richmond Department of Public Utilities, Richmond, VA: Water Treatment Plant - Water Process

The City of Richmond contracted with Hanover, Henrico, and Chesterfield counties to supply them with drinking water.

The contract with Henrico County provides for the purchase of a minimum of 11.8 million gallons/day, up to a maximum of 35 million gallons/day, through the year 2040. After negotiations with Richmond, the city transferred rights to withdraw 80 million gallons/day from the James River to the county in 1994. Henrico County completed its own water treatment plant in 2004. The county will continue to purchase water from Richmond until 2040, giving the city time to amortize its investment in facilities to supply that customer.9

The intake for Henrico's new drinking water treatment plant is upstream of Boshers Dam. The county's long-term water supply will continue to be the James River, but the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) was concerned that increased water removal from the river during a drought would have adverse environmental impacts. Henrico's solution was to stockpile James River water in an off-stream reservoir during times of high flow, and to release that stored "extra" water during droughts.

The Cobb's Creek Reservoir was constructed in Cumberland County, with a capacity to store 14.8 billion gallons. Three earthen dams created the impoundment, and the reservoir began filling in May 2024. Henrico partnered with Cumberland and Powhatan counties to supply their needs as well. The creek's small watershed does not produce sufficient runoff to fill the planned 140-deep reservoir with 15 billion gallons of water, so Henrico will pump James River water behind the dam on Cobb's Creek at times when there is excess runoff (typically in the winter/spring).

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) authorized Cumberland and Powhatan counties to withdraw an additional 47 million gallons per day of raw water per day from the river. Henrico County was assigned 30 million million gallons per day, and the remaining 17 million gallong per day could be shared among the three partners.

No pipeline is planned between the Cobb's Creek Reservoir and Henrico's drinking water treatment plant. Instead, when the James River flow declines below the drinking water needs of the county (and the minimum flow levels required for fish in the river), water will be released from the reservoir upstream. That extra water will flow down the river and be withdrawn at Henrico's current intake near Bosher's Dam.10

The regional Henrico-Richmond cooperation was damaged after the Richmond water treatment plant shut down on January 6, 2025. A power outage led to flooding of critical electrical and pumping systems. Pressure in the distribution system dropped below the threshold, potentially allowing untreated water to infiltrate the pipes. The Boil Water Advisory lasted for five days, and not until January 11 did the city declare that the pipes had been flushed and disinfected adequately. All of eastern Henrico County was affected.

The Virginia Department of Health concluded after an investigation:11

Henrico County decided to spend over $300 million to build a 42" pipeline from the county's water treatment plant west of Richmond at at Three Chopt and Gaskins roads to the eastern edge of the county. County supervisors were no longer willing to trust that Richmond would be a reliable partner providing drinking water. The new pipeline was expected to be operational in 2031. The new pipeline would provide insurance in case of another supply interruption. In addition, it would prrovide leverage when the water supply contract between the city and county expired in 2040.12

Henrico County decided to use taxpayer funds rather than ratepayer funds to build the waterline. In many utilities, new customers pay for new waterline extensions to service their houses or commercial/industrial facilities (under a "growth pays for growth" philosophy), while ratepayers fund the maintenance of existing infrastructure. The $300 million waterline was new, but was needed to ensure reliable delivery of water to existing rather than new customers. County supervisors decided that all residents, not just those connected to public water and sewer, should cover the costs to establish and independent way of delivering water without relying upon Richmond.13