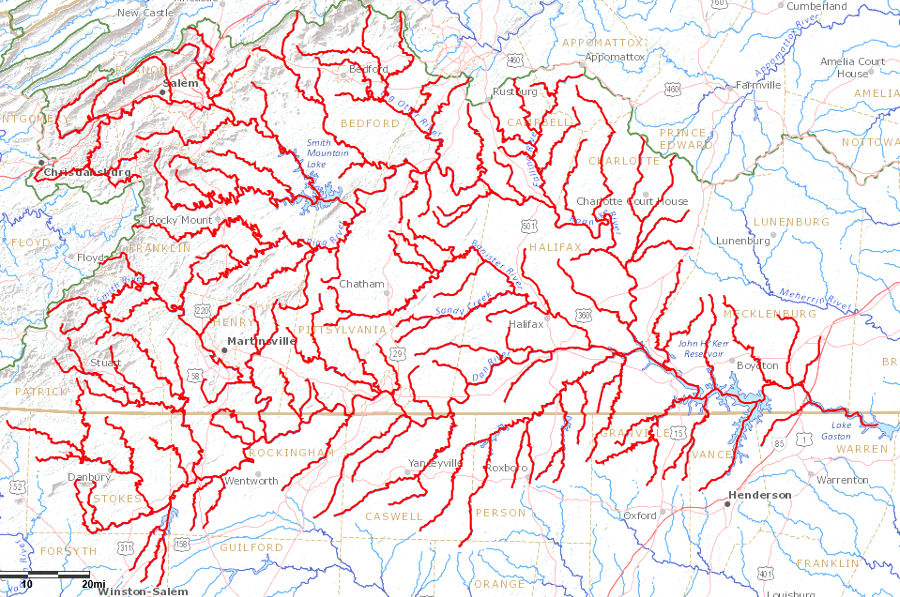

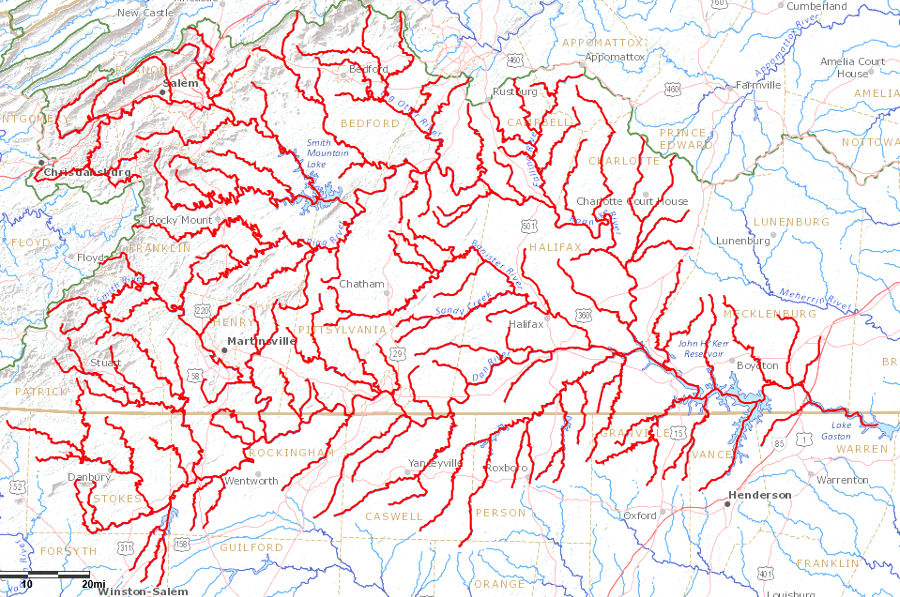

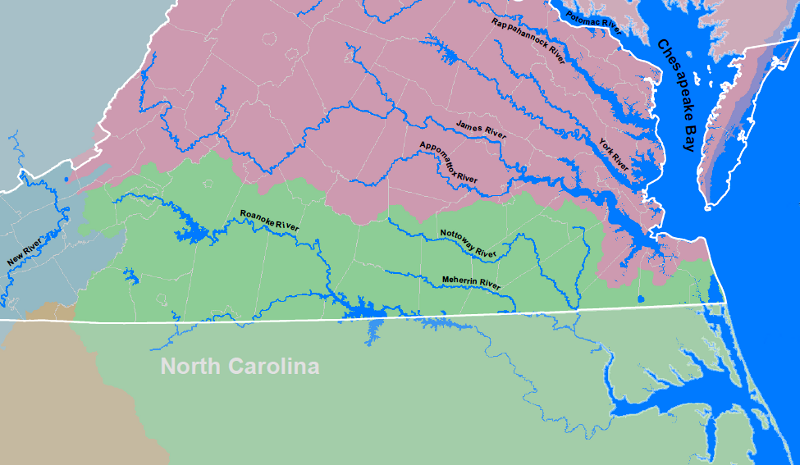

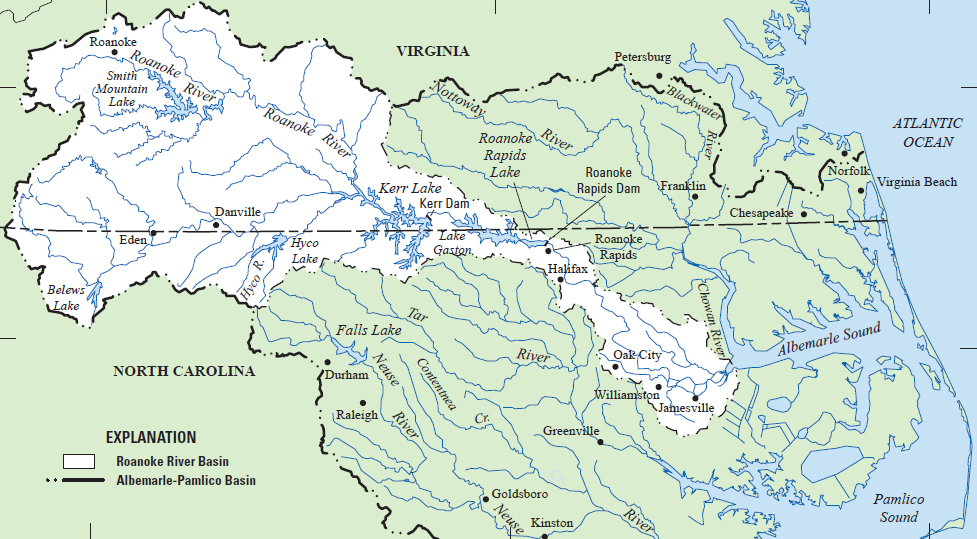

the Roanoke River starts west of the Blue Ridge, travels through the gap at Smith Mountain, and exits into North Carolina at the boundary of Mecklenburg and Brunswick counties

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

the Roanoke River starts west of the Blue Ridge, travels through the gap at Smith Mountain, and exits into North Carolina at the boundary of Mecklenburg and Brunswick counties

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

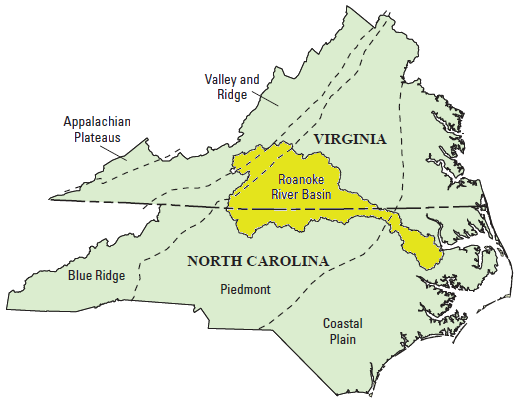

The Roanoke River flows from the Valley and Ridge province through the Blue Ridge, then across the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain to Albemarle Sound. In Virginia, only the Potomac and James rivers also cross through four physiographic provinces.

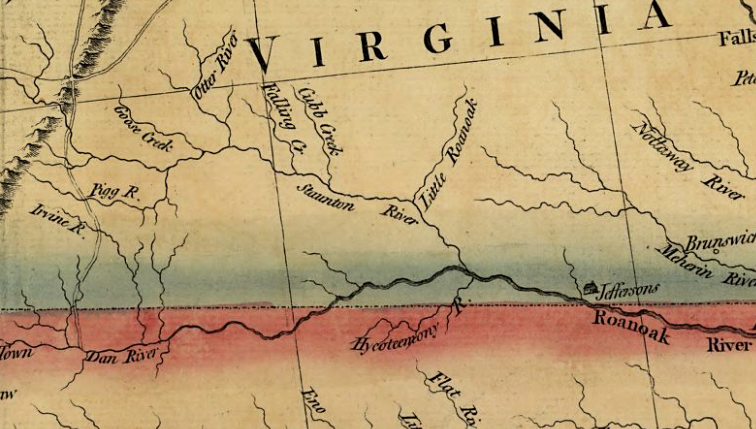

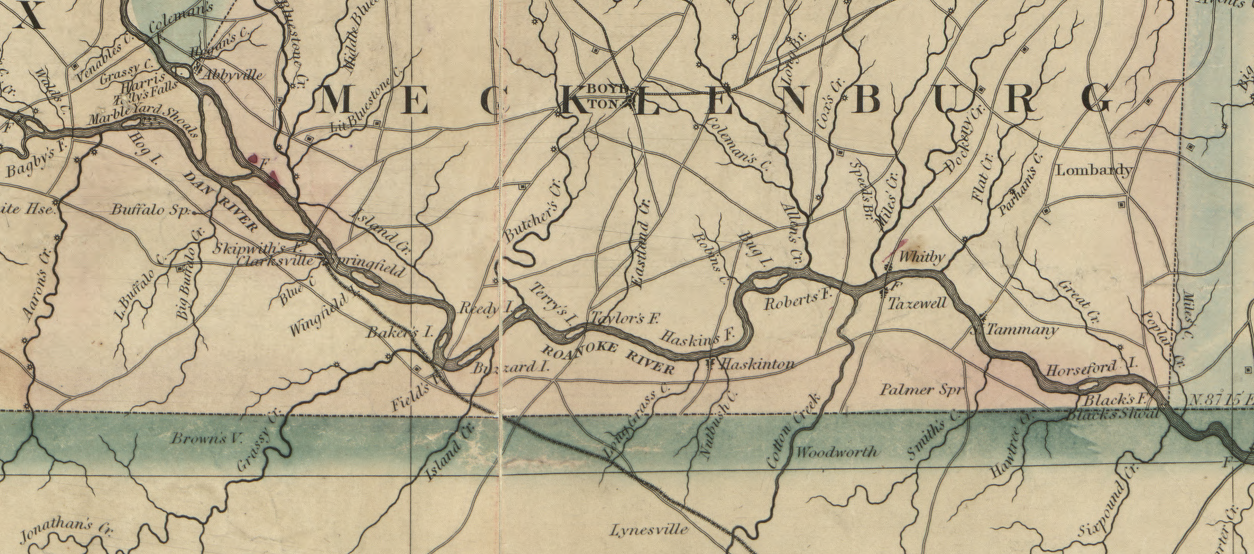

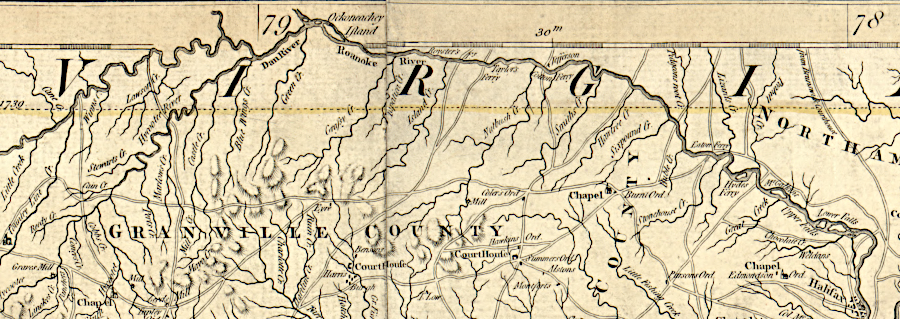

between the Blue Ridge and the confluence with the Dan River, the Roanoke River has also been known as the Staunton River

Source: Library of Congress, A new map of the western parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and North Carolina (1778)

The first English colonists on Roanoke Island in the 1580's explored up the Chowan River towards the Roanoke River. They sought access into the interior, and ideally a Northwest Passage through the continent to the Pacific Ocean. If there were any survivors of the "Lost Colony" of 1587, some may have ended up living along the Roanoke River.

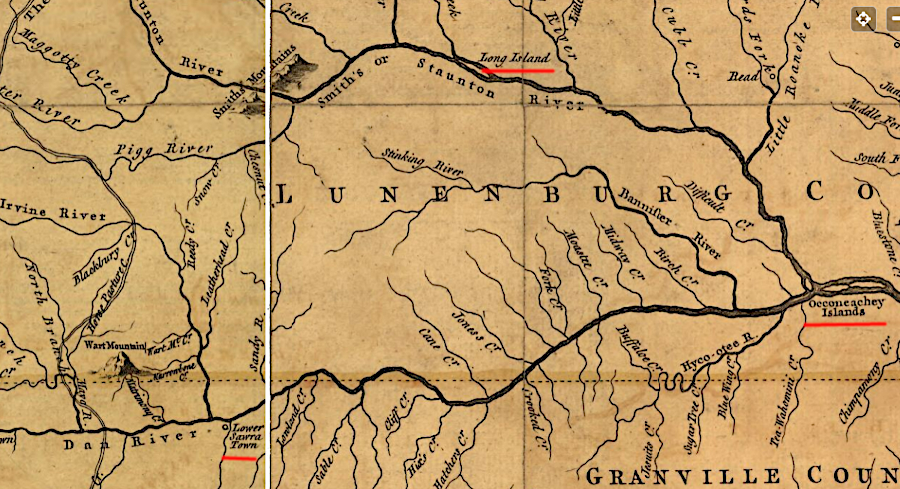

In the 1600's, colonists discovered the watershed was heavily populated by Algonquian-speaking groups at the river's mouth, Iroquoian-speaking tribes to the north and south, and Siouan-speaking towns above the Fall Line. The Occaneechi/Occaneechee developed a trading town near the confluence of the Dan and Roanoke/Staunton rivers, where Native Americans from the Piedmont traded deerskins and furs for English cloth, metal goods, and other products that had been shipped across the Atlantic Ocean.1

Siouan-speaking tribes had towns along the Roanoke River and its tributaries above the Fall Line

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia (by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, 1755)

until 1952, the Roanoke River flowed freely downstream from the confluence with the Dan River

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Clarksville, VA 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1943)

Until the Roanoke River was blocked by the Kerr Dam in 1952, it was a highway for migrating anadromous fish. Starting with the first funding provided in the Pick-Sloan Flood Control Act of 1944 until completion of Gaston Dam in 1963, a series of reservoirs were built that have provided flood control and hydropower since then. The reservoirs also provide a reliable water supply and flat-water recreation for boaters and anglers - but dams have interrupted the normal flow of fish.

the Pick-Sloan Flood Control Act of 1944 authorized a series of dams on the Roanoke River to control floods and generate hydropower

Source: US Department of Agriculture, Legislative History, Public Law 534 - 78th Congress, Chapter 665 - 2d Session, H.R. 4485 (p.7)

Three strains of striped bass may have lived in the river before the dams were built. One strain lived in freshwater upstream of modern Kerr Reservoir and did not migrate. A second strain lived in the middle river and moved to the brackish estuary in the summer, and a third strain spent most of its life in the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean and used the Roanoke River only briefly for spawning.2

After Kerr Dam was completed between 1947-1952 and blocked migration, North Carolina stocked striped bass in the new reservoir and Virginia built the Brookneal Hatchery (now the Vic Thomas Striped Bass Hatchery in Campbell County) to ensure anglers would have striped bass to catch. Today, the Roanoke River between Buggs Island Lake/Kerr Reservoir to Leesville Lake is a popular place to fish for striped bass, during annual spawning runs upstream from Buggs Island Lake/Kerr Reservoir. That stretch of the Roanoke River is known locally as the Staunton River.

striped bass

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Digital Library

anadromous fish could swim upstream past Clarksville before the Kerr Dam was completed in 1952

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Mecklenburg County, Virginia (by George B. Finch, 1870)

The Roanoke River may have been a high-quality highway for fish (and a trading center for the Occaneechi at the site of modern-day Clarksville), but it was a poor transportation corridor for colonial farmers. Farmers living in the Roanoke River watershed lacked a direct water connection to the Chesapeake Bay, since the Roanoke River flowed into Albemarle-Pamlico Sound rather than the Chesapeake Bay. Southside Virginia farmers (south of the James River and west of the Fall Line) were at a competitive disadvantage.

Roanoke River does not flow into the Chesapeake Bay, so farmers in the watershed lacked easy access to transatlantic shipping

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Virginia's Watersheds

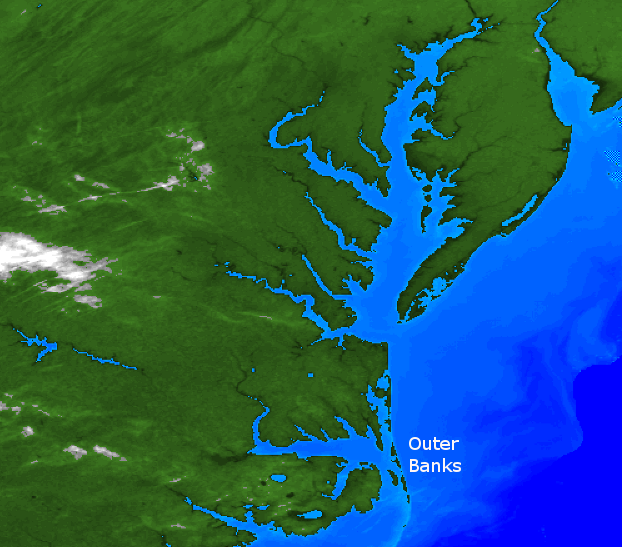

Unfortunately for the Roanoke River farmers, only shallow inlets between the barrier islands connected the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound with the Atlantic Ocean. The pattern of rivers in Southside Virginia, and lack of a good seaport at the mouth of the Roanoke/Chowan River, made it more expensive to ship crops to market. Topography and hydrography shaped economics, and colonial settlement occurred first in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Once settlers moved into the Roanoke River basin of Virginia starting in the 1720's, much of the region's tobacco was shipped by wagon on dirt roads to Petersburg.

the Outer Banks barrier islands limited shipping access from the Atlantic Ocean to the Roanoke River, so port cities developed in the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware Bay watersheds and colonial settlement south of the James River was delayed

Source: National Weather Service, Eighteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes

The Roanoke Navigation Company, chartered in 1804 by the General Assembly, cleared obstacles from 470 miles of river channels and made it easier for farmers to ship lumber, tobacco, corn, wheat, and other agricultural products to market.

Batteaux were often 40-60 feet long and 8 foot wide, designed so they required only 18 inches of water depth. The boats were built to carry loaded hogsheads downstream. Boatmen would use long poles and long steering oars ("sweeps") on both ends of the boat to avoid obstacles on the downstream journey.

A batteau might travel with other boats designed to carry lumber, and at the downstream destination the other boats would be sold for lumber. The investment in building a batteaux was sufficient to bring that boat back upstream, using the crew from the other boats to help.

On the return trip in a mostly-empty batteau, the boatmen used their poles to push the boats upstream against the river current. At the sluices, boatmen would get out of their batteaux, stand on the rock walls, and pull their boats through the fast water in the sluices. The four-foot high, five-foot thick stone "towing walls" were the only place along the shoreline where a towpath was prepared. Unlike the traffic on the James River and Kanawha Canal, on the Roanoke River no mules walked on a riverbank towpath to pull a boat.

Navigation improvements were made on the Roanoke River from Weldon, at the Fall Line near the Virginia/North Carolina border up the Roanoke (Staunton) River to Salem in the valley west of the Blue Ridge. The Dan River was improved 110 miles upstream from its mouth to Madison, North Carolina. Even the Banister River was improved for 25 miles upstream of its confluence with the Dan River to Meadville in Halifax County. Construction also included a canal on the Dan River at Danville, two short canals on the Roanoke River near the Virginia-North Carolina state line, and the major Roanoke River Canal at Weldon with four locks and an aqueduct.

In 1827, Samuel Pannill managed the project to improve navigation from the confluence of the Roanoke (Staunton) River and the Dan River to Salem, 177 miles upstream. Black powder was used to blast a deeper channel through the hard metamorphic rock in the riverbed, carving sluices through the shallow ledges. Rock walls ("wing dams") were constructed at the ledges to divert water into the sluices blasted into the bedrock.

The most challenging section for navigation was the 11.5 mile stretch from the upper end of Long Island downstream to Brookneal. A series of wing dams, towing walls, and excavated channels were constructed by laborers hired by the Roanoke Navigation Company, and by enslaved men which the company bought and sold. Cat Rock Sluice, blasted into the bedrock near Brookneal, has been added to the National Register of Historic Places. The nomination form records that:3

Roanoke River navigation was improved in 1827 by blasting sluices in rock ledges and building wing walls along the shoreline

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 015-0217 Cat Rock Sluice of the Roanoke Navigation

Poling a boat required hard physical labor, whether the trip was downstream or upstream. The boatmen were typically African-Americans, often enslaved. Each trip offered an opportunity to escape. The money from the sale of the crop would have facilitated a flight from slavery. However, the life of a boatman involved a great deal of freedom, with no overseer during trips. Boatmen were also able to make extra money, creating the opportunity to purchase their freedom.4

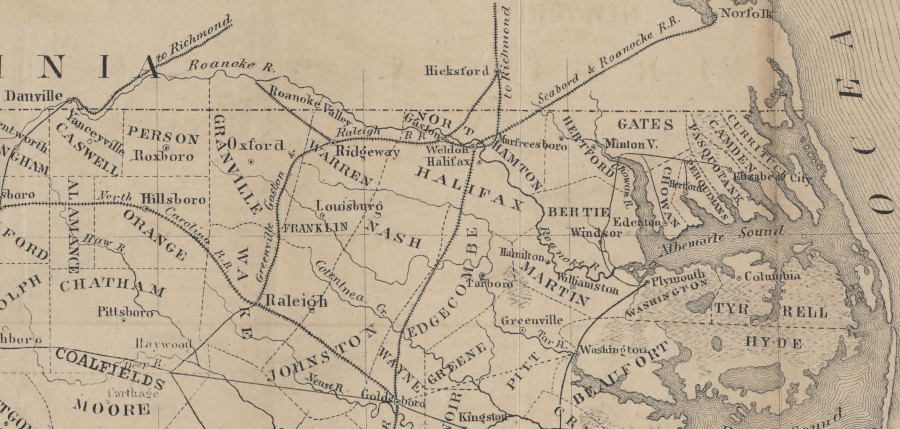

Once the Roanoke River was made navigable and the Dismal Swamp Canal was constructed, Southside farmers could transport their products to Norfolk - providing access to the Caribbean and European markets.

the Roanoke River in Southside Virginia, prior to the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia, constructed in conformity to law from the late surveys authorized by the legislature and other original and authentic documents (1859)

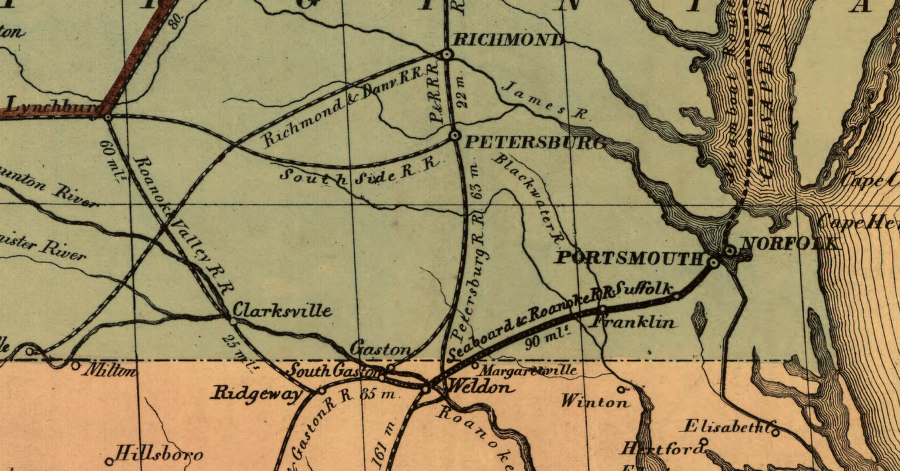

Farmers gained an alternative to shipping agricultural products by boat when railroads were constructed in the watershed. The first in Virginia was the Petersburg Railroad. It began to divert shipments north from Garysburg, on the north bank of the Roanoke River at the Fall Line, to the Appomattox River port in 1832.

The Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad reached Weldon in 1837, diverting freight to the Elizabeth River port. Petersburg merchants reacted by building the Greensville and Roanoke Railroad that year, intercepting trade further upstream before the rapids at the Fall Line. Clearing of trees from the sluices, and repairs of the wing dams and towing walls, apparently ended after 1837. Because of his intimate familiarity with the river, Samuel Pannill probably continued to use the Roanoke River to ship crops from his plantation at Long Island down to Brookneal until he died in 1864.5

Railroad traffic diverted shipping away from the river. In 1833, the Petersburg and Roanoke Railroad reached the north bank of the Roanoke River near Weldon, North Carolina. Later railroads connected to the Roanoke River further upstream. In 1855, the Roanoke Valley Railroad completed its track from Clarksville to Manson, North Carolina. The Richmond and Danville Railroad connected Danville to the James River port in 1856.6

railroads replaced most of the water-based navigation on the Roanoke River prior to the Civil War

Source: University of North Carolina, Outline-map of North Carolina (by George Schroeter, F. Mohr, 1854)

The willingness of the US Congress to fund water infrastructure projects after World War I led to a Corps of Engineers assessment of the Roanoke River watershed. However, the river offered little potential to create a transportation corridor for ships and barges which might have justified a Federal investment in locks and dams to control the river level.

The Corps identified 17 possible projects, but did not find the projected benefits to justify the costs. The Virginia delegation in the US Congress was focused on minimizing the increasing power and costs of Federal government, which was expanding rapidly under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Army Corps of Engineers recommended projects in states with Congressional champions, so possible Roanoke River projects were sidelined:7

During the Great Depression, when Federal funding was provided to build massive water control projects west of the Mississippi River and the Tennessee Valley Authority was created, the US Congress provided no funding for the Roanoke River. However, a 1937 update to the 1936 Flood Control Act did authorize continued study of possible projects in the watershed.

A flood in August, 1940 on the Roanoke River damaged 10,000 acres of cropland. Water washed away tobacco crops, killed livestock, and flooded industrial facilities on the edge of the river such as the Halifax Paper Company mill in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina. In Mecklenburg County, the river crested four feet higher than in the Great Flood of 1877.

Protecting farmland and structures along the Roanoke River then became a Federal priority:8

The Pick-Sloan Flood Control Act of 1944 authorized 11 multi-purpose projects in the Roanoke River drainage basin of 9,580 square miles, with 6,610 square miles (69%) in Virginia and 3,420 square miles (31%) in North Carolina. The legislation authorized $36 million for Buggs Island Reservoir on the Roanoke River and Philpott Reservoir on the Smith River. Those were expected to minimize 90% of the damages that would be caused by a repeat of the 1940 flood.

Between 1947-1952, the US Army Corps of Engineers built what became known as the John H. Kerr Dam across the Roanoke River for the Buggs Island project. Construction was continuous, 365 days a year, for four and a half years.

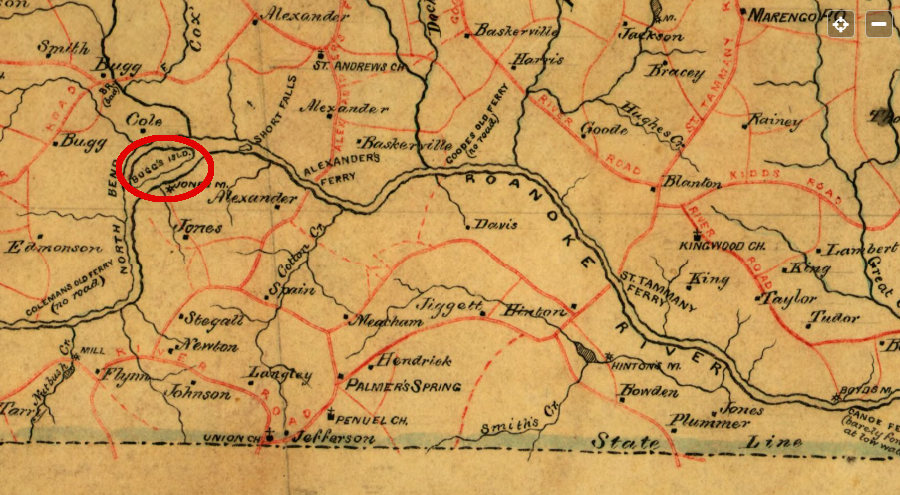

The reservoir behind Kerr Dam is known locally in Virginia as Buggs Island Lake, after an island located below the dam that once was owned by Samuel Bugg.

Confederate engineers documented the location of Buggs Island in 1864

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Mecklensburg, Brunswick and Greensville counties, VA (Confederate Engineer Bureau, 1864)

Buggs Island is just downstream from the dam built by the Army Corps of Engineers across the Roanoke River between 1947-1952

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Boydton VA 1:62,5000 topographic quadrangle (1955)

The Buggs Island project was renamed by the US Congress in 1952. Representative John H. Kerr of North Carolina, who served in the US Congress from 1923-53, is credited with getting Federal funding for the water development project. The 1944 estimate of costs for the Buggs Island Project ended up being far too low; it cost nearly $100 million before completion.

Appalachian Electric Power Company and railroads that hauled coal opposed creation of Federal hydropower on the Roanoke River which might impact private sector profits. Rep. Kerr took the lead in ensuring the additional funding was appropriated, with reliable support from the new Roanoke River Basin Association. Land acquisition of 115,000 acres by the Corps of Engineers for the reservoir displaced 380 families, some of whom were forced to sell through the Federal government's use of eminent domain.

The lake was named by the US Congress to honor Kerr (pronounced "car") soon after he was defeated for renomination in a Democratic primary. Kerr Dam was dedicated on October 3, 1952 as Rep. Kerr was finishing his last term.

The Virginia General Assembly objected to naming a lake that was 2/3 within Virginia after a person from North Carolina. In 1952, the Virginia lewgislature mandated that all official language, including road signs, refer to "Buggs Island Lake" rather than "Kerr Lake" or "John H. Kerr Reservoir."

Virginia officials named the road crossing the dam as Buggs Island Road

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Five decades later, Mecklenburg County officials recognized that consolidating marketing around one name - even if it honored a North Carolina politician - would be more effective in drawing tourists to the area. In addition, "Kerr Lake" had no association with biting and stinging insects.

In 2015 the General Assembly authorized the use of Kerr's name. A state senator representing Mecklenburg County said:9

even in 2024, Buggs Island Lake was the preferred name for some state agencies

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Buggs Island Lake (Kerr Reservoir)

in Virginia, Kerr Reservoir is officially known as Buggs Island Lake

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), John H. Kerr Dam 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)

Construction of the Buggs Island and Phillpott dams had been authorized in 1944 for flood control, recreation, navigation and hydropower purposes. The Water Supply Act of 1958 expanded the general purposes of Corps projects to include municipal and industrial (M&I) uses. No new congressional reauthorization of the project was required, so long as M&I uses were just incidental to operations and did not seriously affects a facility s authorized purposes.10

The missing purpose? Projects designed for irrigation are traditionally constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation, in the Department of the Interior.

in 1943, Occaneechi Island had not been submerged by a dam on the Roanoke River

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Clarksville 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (1943)

In 1984, the Corps of Engineers approved a contract for Virginia Beach to use 1% of the storage space in John H. Kerr Reservoir and to withdraw water out of the Roanoke River Basin, pumping it through a pipeline to the city and its partner, the city of Chesapeake.11

It took longer for the Corps to assess the downstream impacts of water releases from Kerr Reservoir, which are coordinated with hydropower production at the privately-operated Gaston and Roanoke Rapids dams. In the 1990's, after The Nature Conservancy purchased over 10,000 acres from Georgia-Pacific Corporation to create the Roanoke River National Wildlife Refuge, the conservation organization challenged the Corps to alter releases in order to mimic more closely the natural flow of the river. One goal was to alter the hydrological regime to minimize the long-term flooding in the floodplain during the growing season that drowned plants and block normal reproduction by ground nesting birds, and to re-create short-term floods downstream in the springtime to spur striped bass to spawn.

Upstream, the City of Roanoke long ignored the aesthetic and recreational potential of the Roanoke River:12

A major 200-year flood on election day in 1985, triggered by Hurricane Juan, killed 10 people in the Roanoke River valley and caused the river to rise to over 23 feet in the city of Roanoke - where flood stage was 10 feet.13

That event led to a re-examination of the pattern of development and a $65 million flood control project by the Corps of Engineers. Moving structures out of the floodplain offered an opportunity to implement the 1907 recommendations.

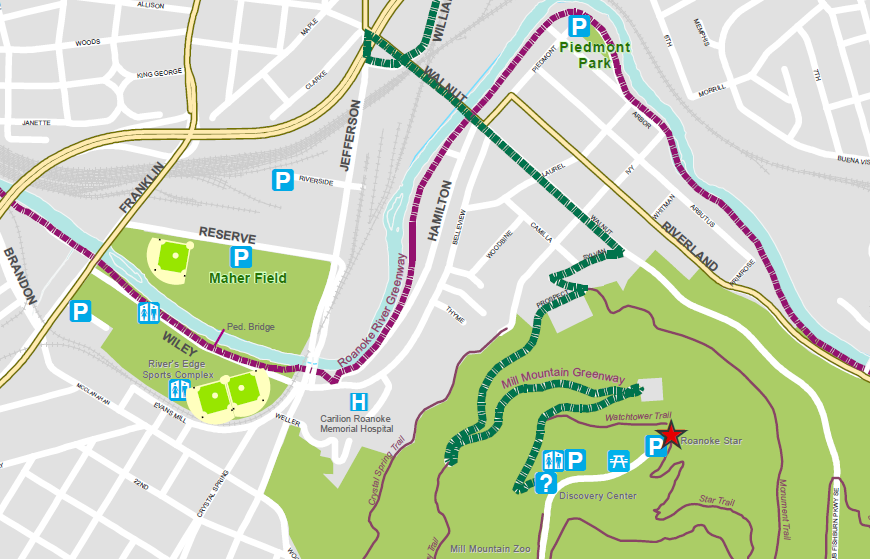

In 1995, the City of Roanoke, Roanoke County, City of Salem, and Town of Vinton adopted the Conceptual Greenway Plan, Roanoke Valley, Virginia. Two years later, they established a regional partnership, the Roanoke Valley Greenway Commission, to implement the plan to build a trail along the Roanoke River.

the Roanoke River Greenway connects to other trails in the urban area, including Mill Mountain

Source: Roanoke Valley Greenways, Maps

prior to the Civil War, multiple railroads planned to intercept traffic on the Roanoke River

Source: Library of Congress, General map of the Orange & Alexandria Rail Road and its connections north, south, and west

the Roanoke River crosses through four physiographic provinces on its journey from near Blacksburg to the Albemarle Sound

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Effects of Flood Control and Other Reservoir Operations on the Water Quality of the Lower Roanoke River, North Carolina (Scientific Investigations Report 2012-5101)

Kerr Dam

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, John H. Kerr Dam and Reservoir

NOTE: The document states that the Dan River was improved to Meade, rather than Madison NC. However, the USGS Geographic Names Information System does not list a "Meade" in North Carolina. One possibility is that Meade was an earlier place name for the town of Madison on the banks of the Dan River, south of Martinsville (see current map and 1895 map). However, Dr. William Trout reports, If it was Henry Howe's "Historical Collections of Virginia," 1845, reprinted 1969, then on page 429 it says "The [Dan] river is navigable for batteaux carrying from 7,000 to 10,000 pounds as far up as Madison, North Carolina." ...I think it was a misprint in an early publication, and it has been repeated ever since. I don't think Madison was ever called Meade. Perhaps there was some confusion with Meadesville (also Meadville) the head of batteau navigation on the Banister at that time. Dan Shaw suggested The author was familiar with Meadville, VA, where George Washington crossed the Bannister River on his way back home on his 1791 Southern Tour. I can only guess she wrote the wrong name and no one ever caught it.

NOTE: The document states that the Dan River was improved to Meade, rather than Madison NC. However, the USGS Geographic Names Information System does not list a "Meade" in North Carolina. One possibility is that Meade was an earlier place name for the town of Madison on the banks of the Dan River, south of Martinsville (see current map and 1895 map). However, Dr. William Trout reports, If it was Henry Howe's "Historical Collections of Virginia," 1845, reprinted 1969, then on page 429 it says "The [Dan] river is navigable for batteaux carrying from 7,000 to 10,000 pounds as far up as Madison, North Carolina." ...I think it was a misprint in an early publication, and it has been repeated ever since. I don't think Madison was ever called Meade. Perhaps there was some confusion with Meadesville (also Meadville) the head of batteau navigation on the Banister at that time. Dan Shaw suggested The author was familiar with Meadville, VA, where George Washington crossed the Bannister River on his way back home on his 1791 Southern Tour. I can only guess she wrote the wrong name and no one ever caught it.

Roanoke River watershed

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Effects of Flood Control and Other Reservoir Operations on the Water Quality of the Lower Roanoke River, North Carolina (Scientific Investigations Report 2012-5101)

in 1775, there were no dams interfering with the flow of the Roanoke River

Source: Library of Congress, An accurate map of North and South Carolina with their Indian frontiers (by Henry Mouzon, 1775)