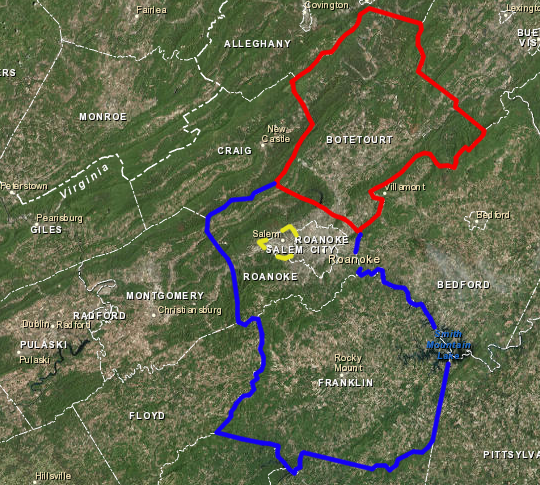

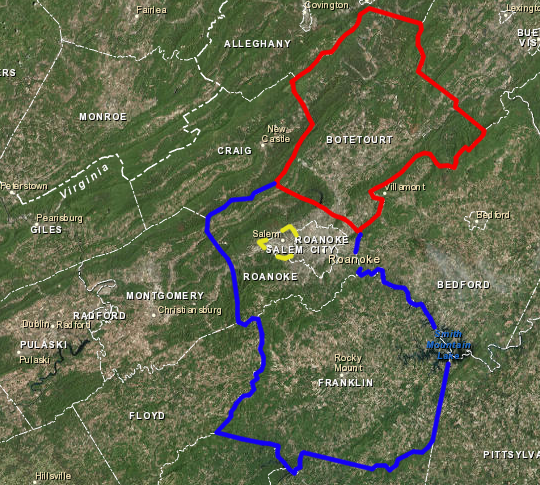

Western Virginia Water Authority

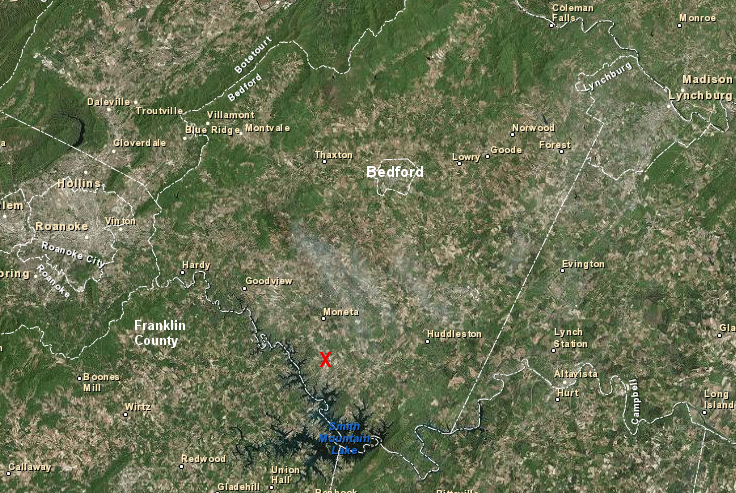

public drinking water sources tapped by jurisdictions in the Roanoke River Valley include Crystal Spring (1), Falling Creek Reservoir (2), Beaver Dam Reservoir (3), Carvins Cove Reservoir (4), Roanoke River at Salem (5), Spring Hollow Reservoir (6), and Smith Mountain Lake (7)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Consolidation of the drinking water systems in the Roanoke River Valley has been a slow process. As the region developed, all communities relied upon the wastewater treatment plant built in 1951 by the City of Roanoke.

The first drinking water system in the valley served both Vinton and the city of Roanoke. However, different jurisdictions tried to keep their independence from each other and created separate drinking water systems for the cities of Roanoke and Salem, the Town of Vinton, and Roanoke County despite the costs (later increased by the Safe Drinking Water Act water quality standards).

In the 1890's, the Vinton-Roanoke Water Company built a reservoir on Falling Creek and developed Smith Spring on Beaverdam Creek in Bedford County. A system of pipes distributed water to customers in the Town of Vinton and the new, rapidly-growing City of Roanoke. The company soon sold its distribution system within the boundaries of Vinton to the town, and committed to supply water at a standard price of $0.05 per 1,000 gallons.

The City of Roanoke acquired the private water company in the 1930's, expanding its water sources beyond Crystal Spring at the base of Mill Mountain. After World War II, Roanoke notified town officials that their water rate would be increased. Vinton refused to pay the higher rate, but the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that Roanoke was entitled to raise the rate. In the mid-1960's, Vinton drilled wells and established an independent drinking water system.1

Roanoke also acquired a separate private water company and its planned reservoir at Happy Valley. By 1928, the Roanoke Water Works had built a dam and started to force 59 families to move, but the Great Depression intervened and the water system was incomplete when purchased by the city.

During World War II, German prisoners of war helped to clear the timber and the remaining structures from the valley, and by 1946 the Carvins Cove reservoir was full. Later, tunnels were dug through Tinker Mountain so Catawba Creek and Tinker Creek could be tapped to fill the Carvins Cove reservoir through interbasin transfers.2

After World War II, the separate jurisdictions in the Roanoke Valley chose to be competitors rather than to cooperate on regional projects. Roanoke built its own civic center (now the Bergulnd Center) and refused to partner in development of the Salem-Roanoke County Civic Center (now the Salem Civil Center). In the 1970's, the refusal to coordinate an upgrade to wastewater treatment facilities led to uncoordinated requests to the State Water Control Board. The chair of that board once expressed frustration at having to serve as the "the Roanoke coordinating board."

When Governor Godwin dedicated the Salem-Roanoke County Civic Center in 1967, his speech gently encouraged more regional cooperation by saying interjusridictional cooperation was fundamental to finding cost-effective government solutions to regional challenges:3

- Whether they be related to water supplies or sewerage disposal or education or recreation needs, with few exceptions, they are the problems not just of one locality but of two or more... There may have been a day in Virginia when residents of a village or a county could afford the luxury of exclusiveness, or when it really did not matter so much that hands seldom reached across boundaries in mutual trust and concern. In this day, however, we realized that no community can be an island unto itself... One locality's problems inevitably spill over its lines to affect the inhabitants on the other side and no amount of disinterest can make them go away.

The City of Salem built its own water system in the 1970's. Salem relied upon the Roanoke River as its only water source, initially. In 1979, the Matthews Electroplating site two miles upstream of Salem was designated as a Superfund hazardous waste site by the Environmental Protection Agency, after chromium, nickel, and cyanide was discharged into a sinkhole and local wells were contaminated. That heightened awareness of the benefits of having alternative sources of supply.

When a new water treatment plant was constructed in 2003, the city also dug wells to use local groundwater as a second source. The wells, drilled into limestone, can supply two million gallons per day. In case of an emergency, Salem's water system is also connected to the pipes of the Western Virginia Water Authority.4

Roanoke County initially contracted with the City of Roanoke and City of Roanoke to supply drinking water to new suburban developments and retail centers as the suburbs grew in the county. In the 1980's, Roanoke County officials realized that their need for drinking water would exceed the future supply and that the current source of water was not guaranteed. The two cities could stop their sales of water.

The various jurisdiction in the region, including Bedford County, examined various possible sources for additional drinking water. One option was to build a pipeline from the Roanoke River to the City of Roanoke's Carvins Cove reservoir. The Roanoke River Carvins Cove Raw Water Interconnect was a logical option because the river had a surplus of water in the winter, while the watershed for Carvins Cove was tiny and the reservoir had a surplus of storage space.

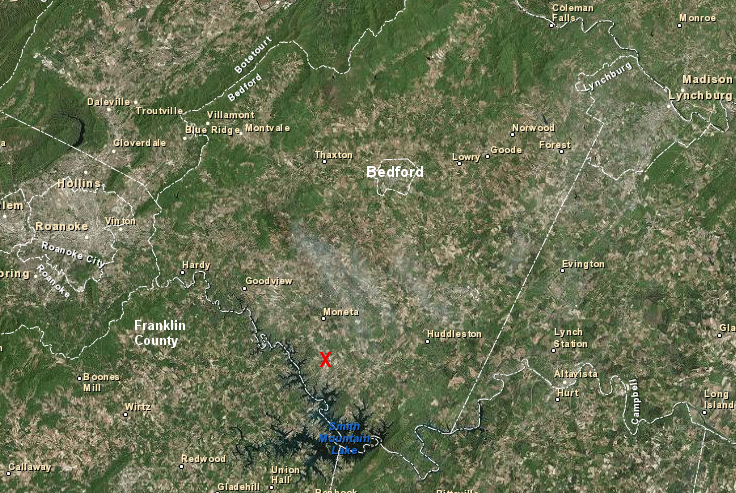

Another alternative was to build a pipeline from Smith Mountain Lake. There was a large amount of water in that reservoir, though American Electric Power Company would have to be compensated for the loss of electricity that would not be generated if water was diverted before it flowed through the dam.5

Roanoke City, Roanoke County, and the City of Salem chose to partner together, share costs, and build a new reservoir next to the Roanoke River.

Initially the new reservoir was planned to be located on a tributary just downstream from the confluence of the river's north and south forks, at Lafayette near the border with Montgomery County.

To avoid the environmental impacts of damming the main stem of the Roanoke River, the various jurisdictions chose instead to build a side-stream reservoir on tiny Mill Branch and fill the Spring Hill Reservoir by pumping water from the Roanoke River during periods of high flow. To address wildlife and environmental concerns, at least 30% of the flow would have to be left in the river at all times, and during the April/May spawning season 40% would be left for the fish.6

Spring Hollow Reservoir was built by Roanoke County in 1996, after the City of Roanoke pulled out of the project

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Elliston 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013)

Plans are only plans, and the rivalries between the cities of Salem and Roanoke were hard to overcome. The proposal to build the Spring Hill Reservoir collapsed after the two cities determined that their costs would exceed their perceived benefits.

In addition to assessing how much water could be stored and at what price, city officials also considered impacts on regional politics. The City of Roanoke traditionally had overcharged Roanoke County customers for water, and the city's control over the drinking water supply was used as leverage when negotiating regional deals. Creating a neutral regional water supply system would require City of Roanoke officials to deal with Roanoke County officials differently.

After the cities of Roanoke and Salem withdrew from the planned regional water supply system, they were surprised in 1994 when Roanoke County decided to build the Spring Hill Reservoir on its own. The county was able to fund the project without financial support from the cities. Roanoake County incurred extra expense and built extra pipes in order to bypass city pipes; that allowed Roanoke County to transport water from Spring Hill Reservoi independently. Had the jurisdictions chosen to cooperate, the costs of using existing city infrastructure would have been lower.

The 1998-99 drought added new pressure on the City of Roanoke to find a reliable water supply, and city officials almost reached a deal with Roanoke County to create a regional partnership for managing drinking water. After rainfall increased and the crisis passed, so did the commitment to partner. The plan stalled, and the county proceeded with building the new Spring Hill Reservoir at its own expense.

During the 2002 drought, water levels in Carvins Cove dropped to record low levels; the City of Roanoke was threatened again with a water shortage. The city-managed wastewater treatment plant also faced expensive upgrades to meet increasingly-strict water quality standards. The future requirements and costs identified in the 2003 Long Range Water Supply Study supplied the rationale for different systems managed by separate jurisdictions in the Roanoke Valley.

In 2004, the utility departments of Roanoke City and Roanoke County consolidated to form the Western Virginia Water Authority. Franklin County joined in 2009 and Botetourt County in 2015. The authority took over the utility system of the Town of Boones Mill in 2021, and the Town of Vinton system in 2022.

Together they now share a drinking water system supplied from Spring Hollow Reservoir, Carvins Cove Reservoir, Crystal Spring, Falling Creek Reservoir, Smith Mountain Lake, and multiple wells extracting groundwater. Costs for treating wastewater are allocated based on the amount of sewage sent to the regional facility.

The Western Virginia Water Authority consists of three appointees from the City of Roanoke, three appointees from Roanoke County, one appointee from Franklin County, and one appointee from Botetourt County. The City of Salem still mnages its water and sewer systems as a separate utility.7

The City of Salem has maintained its independence for drinking water. In 2005, it completed a new drinking water treatment plant with a capacity of 10 million gallons per day, supplied by the Roanoke River plus some groundwater wells.8

Botetourt County (red line) joined the Western Virginia Water Authority in 2015, partnering with the City of Roanoke, Roanoke County, and Franklin County - but the City of Salem (yellow line) continued to maintain separate water/wastewater systems

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Western Virginia Water Authority discovered in 2014 that its three million gallon concrete underground tank at Crystal Springs (in the City of Roanoke) was leaking 500 gallons a minute, 262 million gallons/year. The total was ten times the amount previously estimated.

That amount of leaking water, already treated to be drinking water quality, was worth $250,000/year. Because the water distribution system had already been expanded, the authority no longer needed the large storage reservoir built in 1905 at Crystal Springs. Building a 300,000 gallon replacement tank, for $1.5 million, would result in $1.5 million in savings within a short payback period of just six years.

The Western Virginia Water Authority estimated that 22% of the treated drinking water disappears from its system through leaks or from "nonrevenue water" withdrawn from fire hydrants. The leak at Crystal Spring was one-fifth of the Western Virginia Water Authority system's total loss. Older water systems may lose 40% of the water they treat, while newer systems with tighter pipe joints and less inflow and infiltration (I&I) may lose just 10%.9

Creating a reliable regional water supply has helpful in attracting new businesses to the region. A year after Botetourt County joined the Western Virginia Water Authority, a brewery chose to locate in the Botetourt Center at Greenfield industrial park. In 2025, when Google decided to build a data center there, the benefits of the regional approach were noted in a Cardinal News article:10

- If every locality in the Roanoke Valley had insisted on going it alone with a separate water supply (as some voices years ago thought they should), Botetourt wouldn't have landed the Ballast Point (now Constellation) brewery or Google. When those brewery workers or future Google workers spend their money in Roanoke or Roanoke County or Salem, everybody benefits.

Public concerns about the Google data center included questions regarding the adequacy of the water supply to cool the computer servers. The Western Virginia Water Authority had capacity to supply 58 million gallons/day to its customers. The plant at the Spring Hollow Reservoir could produce 18 million gallons/day of drinking water. The Carvins Cove treatment facility capacity was 28 million gallons/day. Other sources were the Falling Creek/Beaver Dam Creek reservoirs and Crystal Springs.

Western Virginia Water Authority demand in 2025 was only 20 million gallons per day. Google's water-cooled hyperscale data center in the Greenfield industrial park might use 2 million gallons per day initially, with a maximum demand around 8 million gallons per day.

At peak demand, that level could strain the supply from Carvins Cove Reservoir. The Constellation Brands brewery in the Botetourt County industrial park, developed originally by Ballast Point, used about 200,000 gallons per day to make beer. There was strong local support for efforts to attract another brewery, with few concerns about how such a facility would impact the Carvin Cove Reservoir.

The editor of Cardinal News opined:11

- By building the Spring Hollow reservoir in the 1990s, forming the regional water authority in 2004 and adding a water treatment plant to draw from Smith Mountain Lake in 2017, the Roanoke Valley has made itself a water-rich region. There may well be good reasons to oppose Google, but its water demand doesn't seem to be one of them.

Google's initial water demand was estimated at 2,000,000 gallons of water per day, growing to a maximum of 8,000,000 gallons per day. In 2025, the largest customer for the Western Virginia Water Authority was a Coca-Cola bottling plant that required 270,000 gallons per day.

In 2025, the 25,000 customers in the City of Salem used 4,500,000 gallons per day. Typical water-cooled data centers used 1,000,000-5,000,000 gallons per day. Google's proposed $1 billion project in Botetourt County was expected to be a supersized complex to handle artificial intelligence (AI) processing. The complex would have the greatest water demand of any data center in Virginia.12

Google could minimize its water demand by cooling the data center with air conditioning; that would increase use of electricity rather than water. Another option was to use treated wastewater, a "purple pipe" cooling system.

Botetourt County committed to provide replacement water to Carvin's Cove. Roanoke city officials worried that Google would withdraw enough water to cause the reservoir level to fluctuate and diminish recreational and scenic values.

Botetourt County agreed to fund a replacement water project, paying the first $100 million and then a lower percentage for up to $300 million. Replacement of water drawn from Carvins Cove could involve building a new reservoir. Before Google, the Western Virginia Water Authority had not anticipated a new reservoir would be needed for 35 years. The executive director of the authority said about Botetourt County water supply planning:13

- The county, to their credit, also recognized that for them to attract economic development... that maybe a water source in addition to Carvins Cove would be useful for them instead of having to rely on Carvins Cove as their primary source.

Both the City of Roanoke and Roanoke County also requested Botetourt County give them 15% of the tax revenues generated by Google until the replacement water supply was available. The two jurisdictions justified that request by citing their previous contributions of Carvins Cove and Spring Hill Reservoir to the Western Virginia Water Authority. A Roanoke County supervisor said:14

- The first knee-jerk reaction from any of us on the board is, you know, "Are we going to be sacrificing drinking water for chip water, for cooling down chips?"

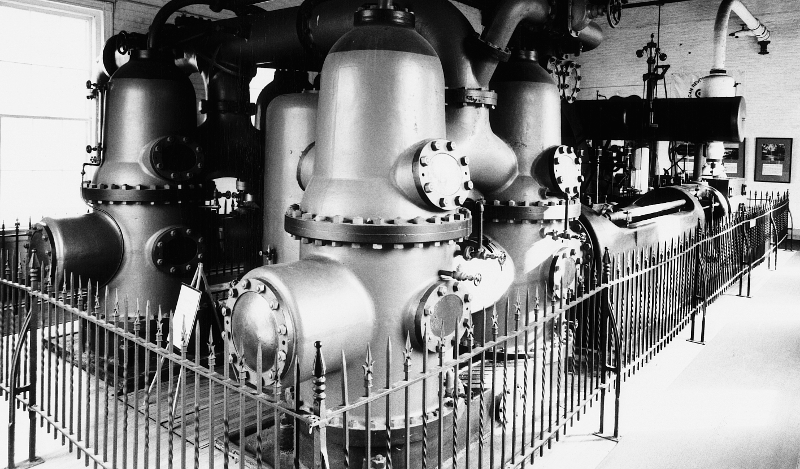

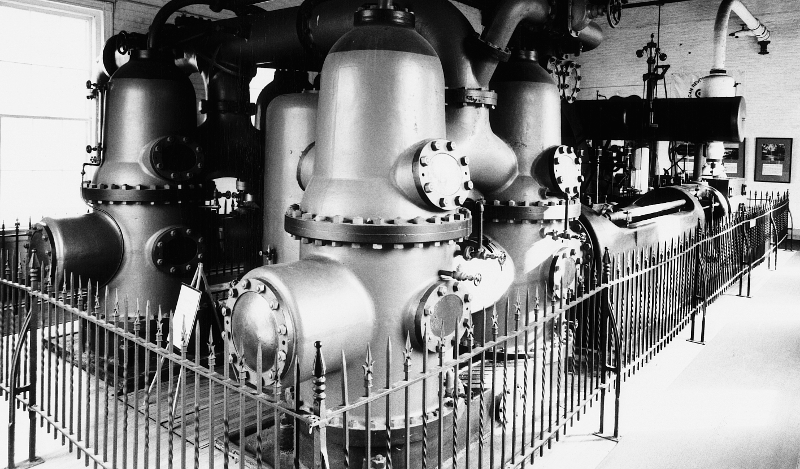

the Crystal Spring pump operated from 1905-1958, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Crystal Spring Steam Pumping Station

Links

References

1. "Town of Vinton v. City of Roanoke," Supreme Court of Virginia, 195 Va. 881 (1954), http://law.justia.com/cases/virginia/supreme-court/1954/4169-1.html; "The Town of Vinton tests new water well," WSLS-TV (Roanoke, VA), January 14, 1965, WSLS-TV (Roanoke, VA) News Film Collection, 1951 to 1971 in Virgo (University of Virginia Library), http://search.lib.virginia.edu/catalog/uva-lib:2237478 (last checked August 26, 2014)

2. "Happy Valley," RIMBA News blog, Roanoke Chapter of the International Mountain Bicycling Association, February 14, 2014, http://news.roanokeimba.org/2014/02/14/happy-valley/; "Carvins Cove Nature Reserve," WDBJ7-TV, October 18, 2011, http://articles.wdbj7.com/2011-10-18/dam_30294282 (last checked August 26, 2014)

3. "Roanoke's request for 15% of Botetourt's tax revenue from Google data center is unprecedented. It also harkens to a darker era in the Roanoke Valley," Cardinal News, July 24, 2025, https://cardinalnews.org/2025/07/24/roanokes-request-for-15-of-botetourts-tax-revenue-from-google-data-center-is-unprecedented-it-also-harkens-to-a-darker-era-in-the-roanoke-valley/ (last checked July 24, 2025)

4. "Water and Sewer," City of Salem, https://www.salemva.gov/439/Water-Sewer; "Matthews Electroplating," Mid-Atlantic Superfund, Environmental Protection Agency, http://www.epa.gov/reg3hwmd/npl/VAD980712970.htm; "Long-Range Water Supply System Study for Bedford County, Botetourt County, Franklin County, Roanoke County, City of Roanoke, City of Salem, and the Town of Vinton," Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Regional Commission, July 18, 2003, p.19, http://rvarc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/water.pdf (last checked July 30, 2025)

5. "Long-Range Water Supply System Study for Bedford County, Botetourt County, Franklin County, Roanoke County, City of Roanoke, City of Salem, and the Town of Vinton," Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Regional Commission, July 18, 2003, pp.4-17, http://rvarc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/water.pdf (last checked August 26, 2014)

6. "Side-stream reservoir ensures water future," American City and County, July 1, 1996, http://americancityandcounty.com/mag/government_sidestream_resrvoir_ensures (last checked August 26, 2014)

7. "Regional Projects," Powerpoint presented at Infrastructure Financing Conference, December 14, 2012, http://www.virginiaresources.org/pdf/IFC2012%20presentations/Dec14_830GH_RegionalProjects.pdf; "History and Development," Western Virginia Water Authority, http://www.roanokeva.gov/85256A8D0062AF37/vwContentByKey/N25ZJRMV262JEASEN; "Botetourt County votes to join regional water authority," The Roanoke Times, April 28, 2015, http://www.roanoke.com/news/local/botetourt_county/botetourt-county-votes-to-join-regional-water-authority/article_8653424b-9244-5b65-9fff-4c659ca772f4.html"Drought busting: Decisions 20 years ago secured Roanoke Valley's water future," The Roanoke Times, July 28, 2024, https://roanoke.com/news/local/carvins-cove-spring-hollow-drought-western-virginia-water-authority-roanoke-city-county/article_e52d22fe-4865-11ef-9440-6f82e4d7464c.html; "History of the Authority," Western Virginia Water Authority, https://www.westernvawater.org/about-us/general-information/history-and-development (last checked July 30, 2024)

8. Water and Sewer Department, City of Salem, http://www.salemva.gov/departments/water/WaterSewerDept.aspx (last checked April 28, 2015)

9. "Major leak to be fixed at Roanoke's Crystal Spring Reservoir," The Roanoke Times, May 20, 2014, http://www.roanoke.com/news/local/roanoke/major-leak-to-be-fixed-at-roanoke-s-crystal-spring/article_ecd8aba4-e083-11e3-a155-001a4bcf6878.html; "Annual Comprehensive Financial Report," Western Virginia Water Authority, June 30, 2024, p.12, https://www.westernvawater.org/home/showpublisheddocument/14095/638693698367430000 (last checked June 30, 2025)

10. "Why Google's data center project in Botetourt gets applause while others don't and how the planning for it began long before the web even existed," Cardinal News, June 25, 2025, https://cardinalnews.org/2025/06/25/why-googles-data-center-project-in-botetourt-gets-applause-while-others-dont-and-how-the-planning-for-it-began-long-before-the-web-even-existed/ (last checked June 25, 2025)

11. "8 things to know about Google's data center deal in Botetourt County," Cardinal News, June 30, 2025, https://cardinalnews.org/2025/06/30/8-things-to-know-about-googles-data-center-deal-in-botetourt-county/; "Annual Comprehensive Financial Report," Western Virginia Water Authority, June 30, 2024, p.3, https://www.westernvawater.org/home/showpublisheddocument/14095/638693698367430000; "Roanoke's request for 15% of Botetourt's tax revenue from Google data center is unprecedented. It also harkens to a darker era in the Roanoke Valley," Cardinal News, July 24, 2025, https://cardinalnews.org/2025/07/24/roanokes-request-for-15-of-botetourts-tax-revenue-from-google-data-center-is-unprecedented-it-also-harkens-to-a-darker-era-in-the-roanoke-valley/ (last checked July 24, 2025)

12. "Potential Botetourt Data Center Could Be Google's Thirstiest in Virginia, Prompting Water Wars," Roanoke Rambler, July 29, 2025, https://www.roanokerambler.com/potential-botetourt-data-center-could-be-googles-thirstiest-in-virginia-prompting-water-wars/ (last checked July 30, 2025)

13. "Roanoke seeks share of Botetourt County's Google data center tax revenues," Cardinal News, July 17, 2025, https://cardinalnews.org/2025/07/17/roanoke-seeks-share-of-botetourt-countys-google-data-center-tax-revenues/ (last checked July 17, 2025)

14. "Roanoke seeks share of Botetourt County's Google data center tax revenues," Cardinal News, July 17, 2025, https://cardinalnews.org/2025/07/17/roanoke-seeks-share-of-botetourt-countys-google-data-center-tax-revenues/; "Potential Botetourt Data Center Could Be Google's Thirstiest in Virginia, Prompting Water Wars," Roanoke Rambler, July 29, 2025, https://www.roanokerambler.com/potential-botetourt-data-center-could-be-googles-thirstiest-in-virginia-prompting-water-wars/ (last checked July 30, 2025)

Bedford Regional Water Authority and Western Virginia Water Authority partnered to build the Smith Mountain Lake Water Treatment Plant (red X) near Moneta to provide 6 million gallons/day (and up to double that amount at peak times) to the Town of Bedford, the Lynchburg suburb of Forest, and also to Franklin County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Rivers and Watersheds of Virginia

Virginia Places