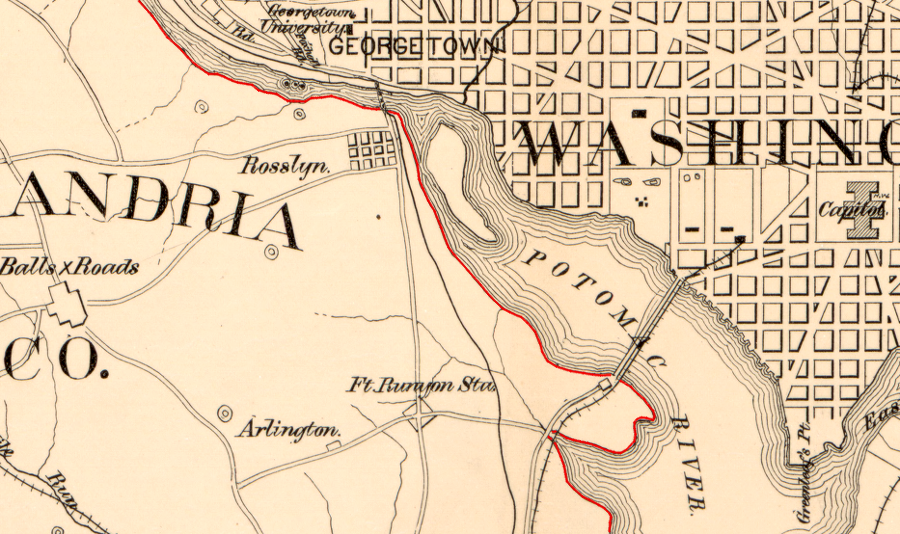

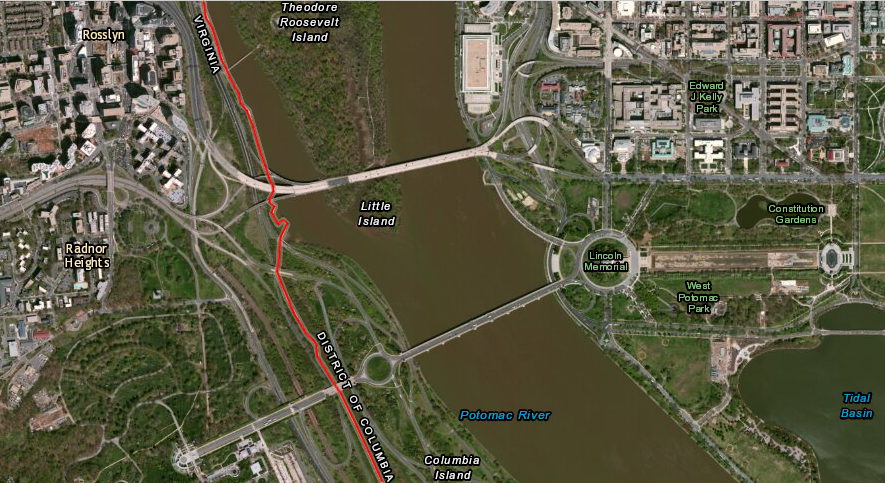

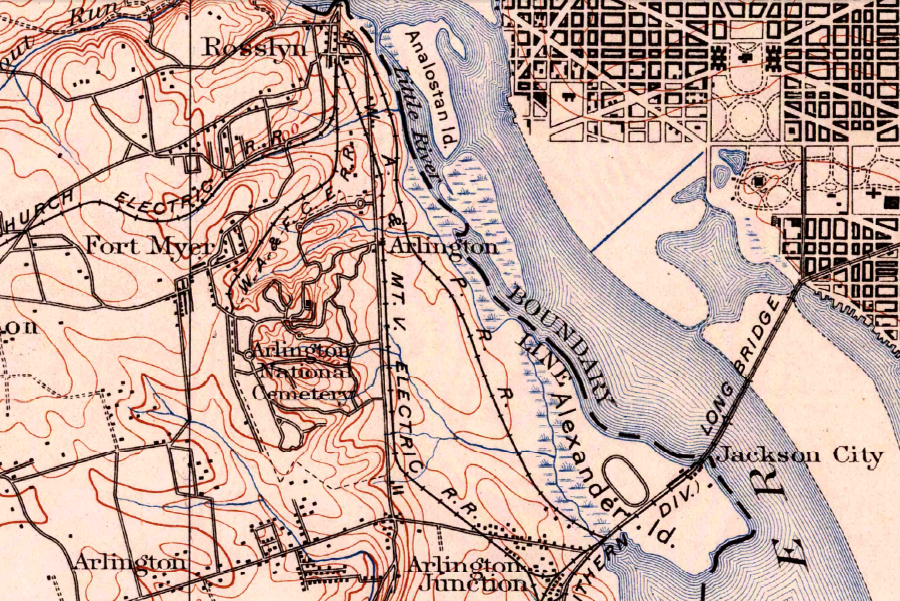

the boundary between Virginia-District of Columbia became the low-water mark on the Virginia shoreline between 1791-1801, and after retrocession in 1847

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Washington D.C. and vicinity (186__)

the boundary between Virginia-District of Columbia became the low-water mark on the Virginia shoreline between 1791-1801, and after retrocession in 1847

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Washington D.C. and vicinity (186__)

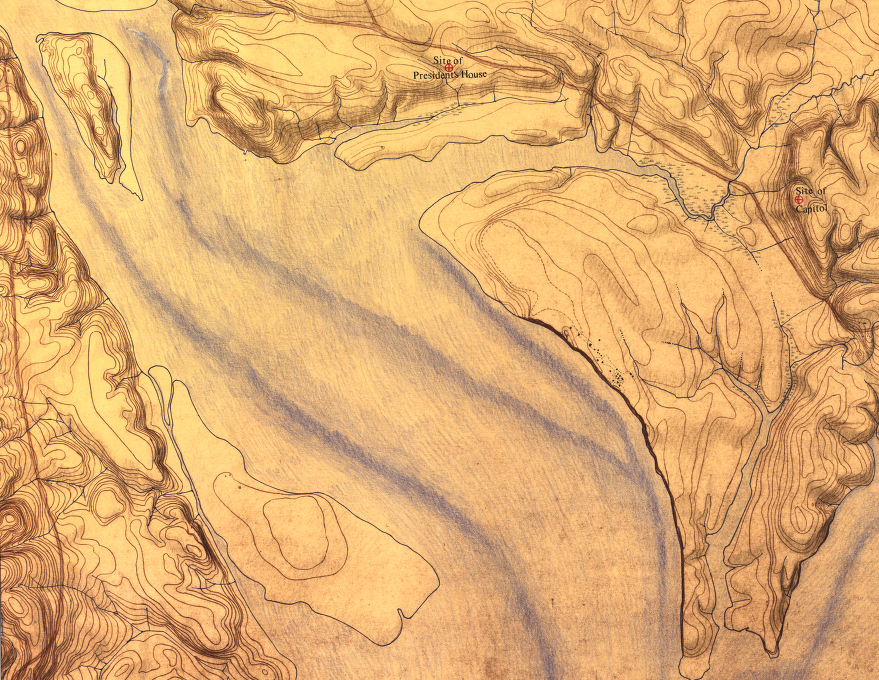

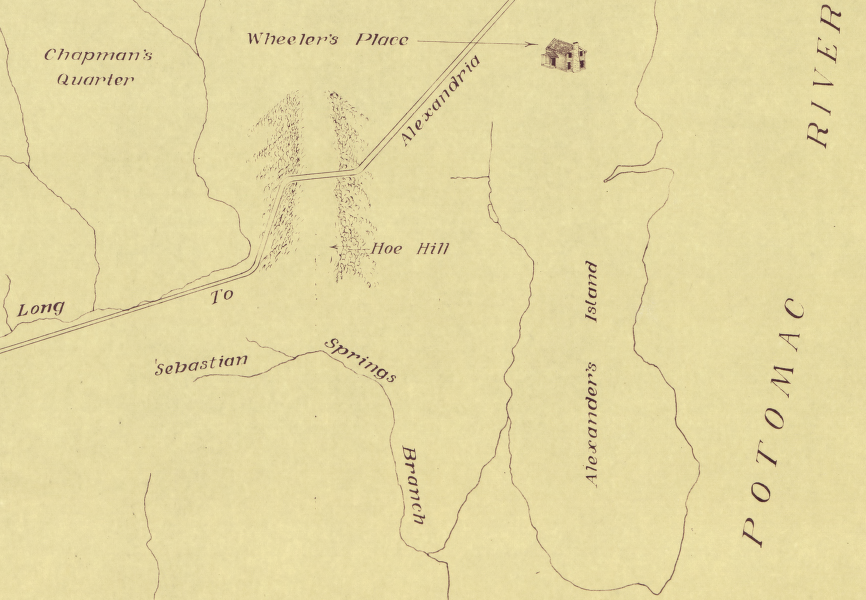

When Charles I granted Lord Calvert a proprietary colony in 1632, the king gave away "his land" and reduced the size of Virginia as defined in its 1609 Second Charter from James I. Lord Calvert was given land south of the 40° line of latitude and north of the Potomac River.

The southern edge of the new colony of Maryland was defined as the "further Bank of the said River." The new boundary was not the middle of the Potomac River, it was the riverbank on the south side. There was confusion for several centuries regarding whether the line of the riverbank was the high water mark or the low water mark.

The Virginia-Maryland boundary has remained the edge of the Potomac River, but nearly 14 miles of shoreline has become the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary. That change first happened for 10 years between 1791-1801, and then again after 1847.1

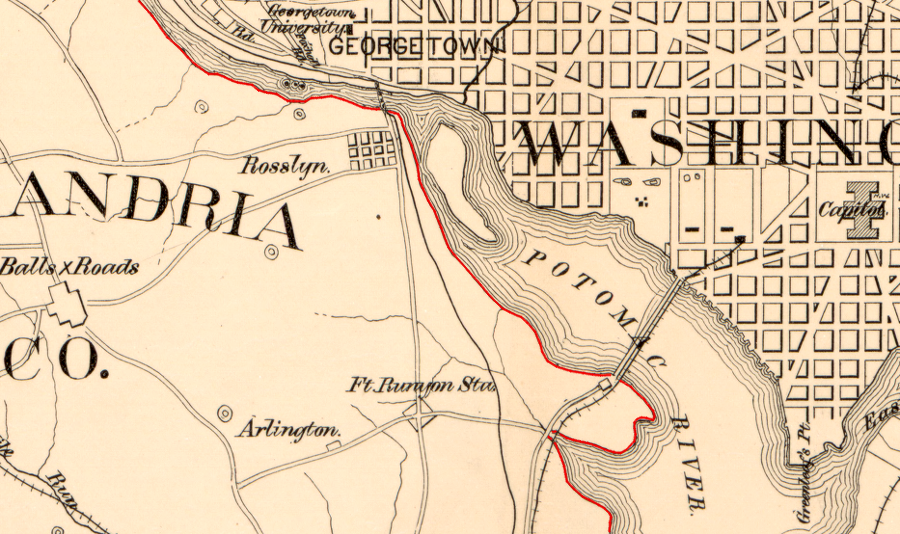

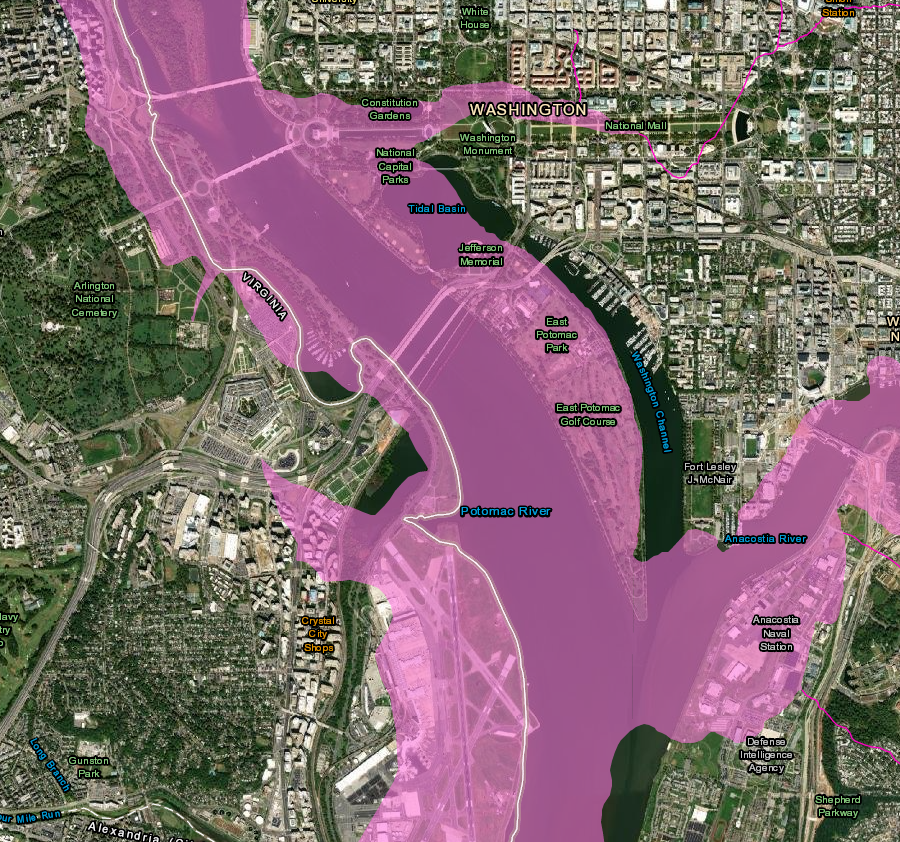

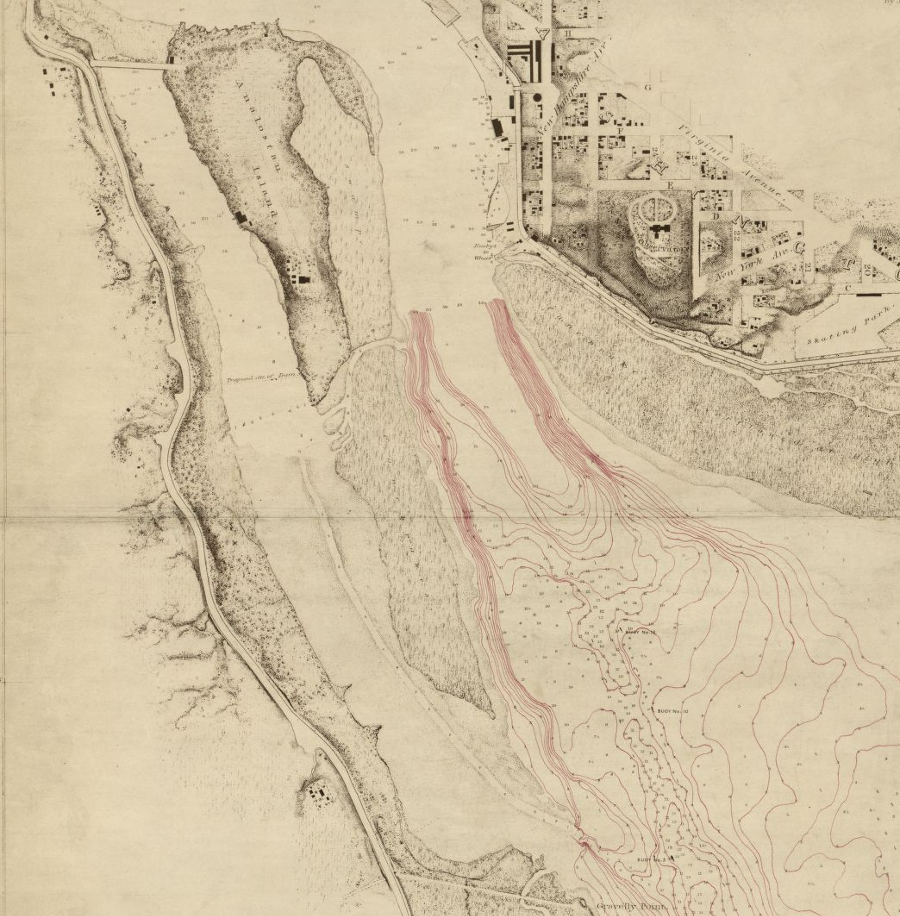

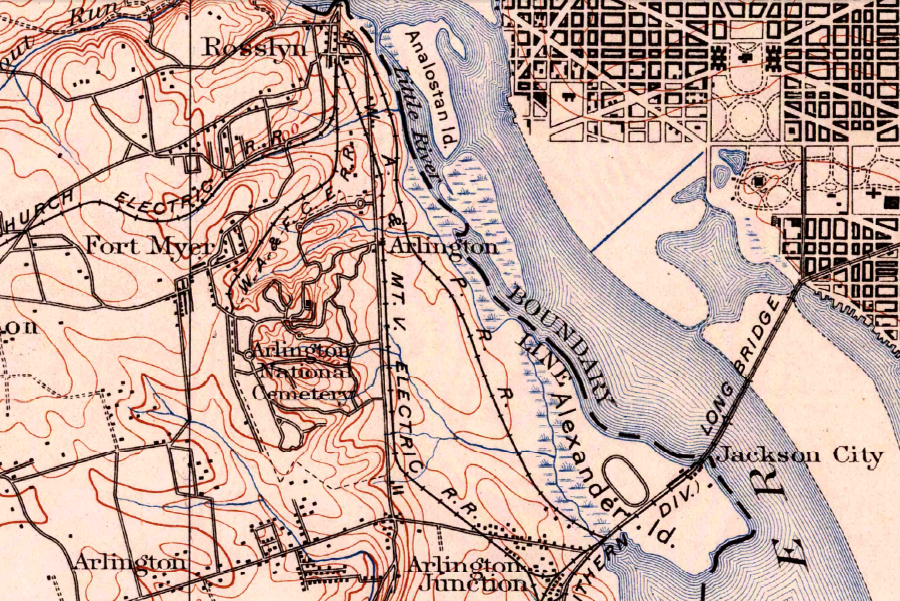

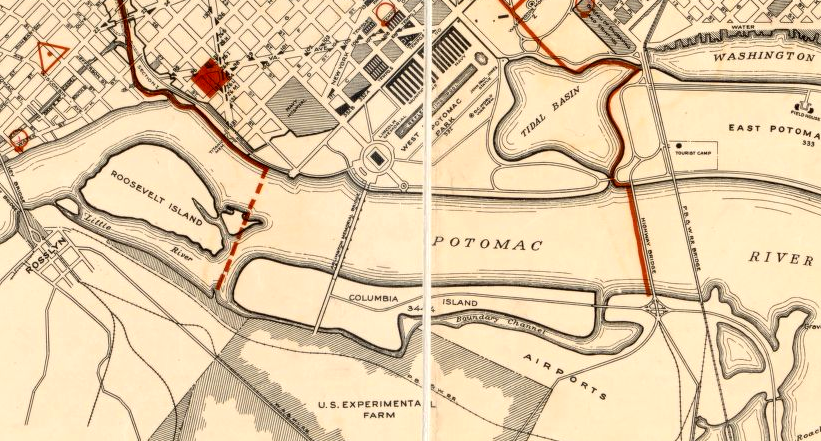

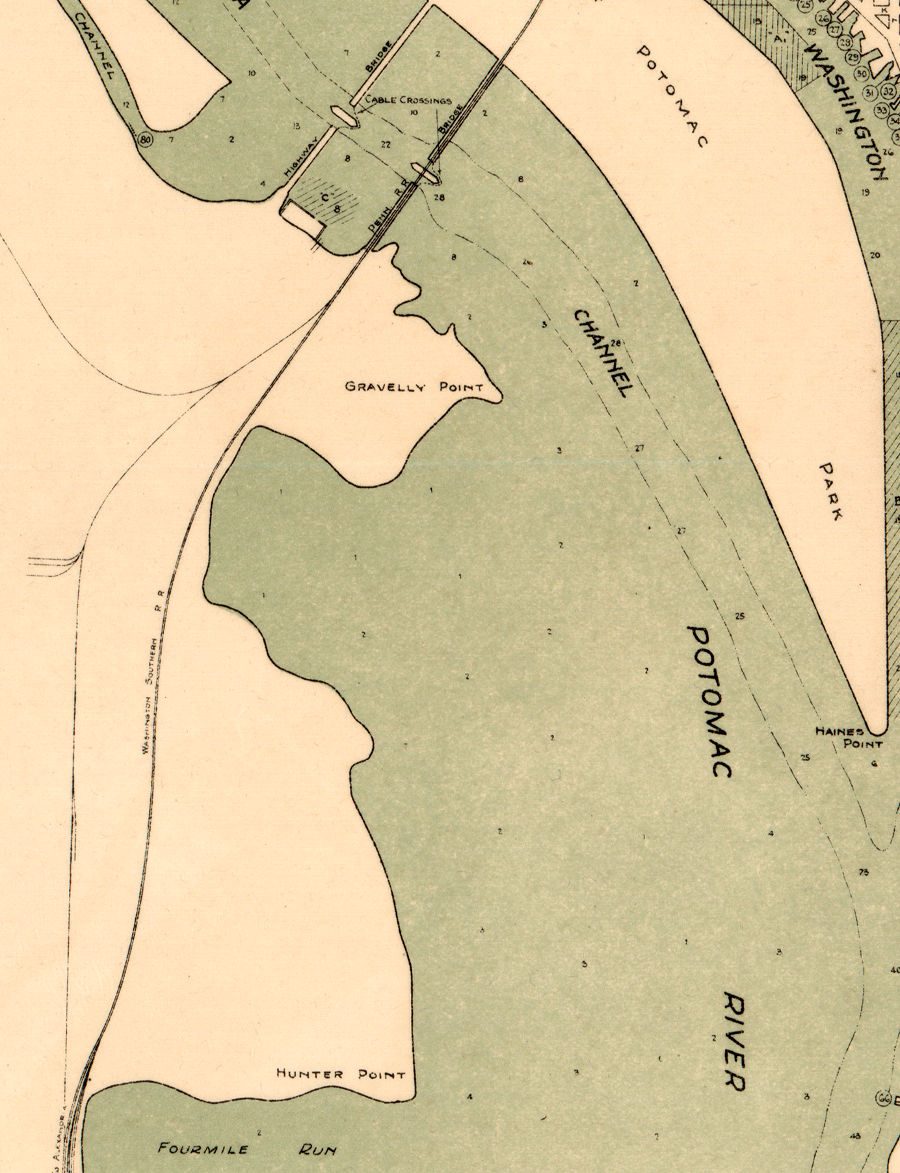

the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary, defined by the 1791 shoreline, was transformed by the 1940's after fill dirt was deposited in the marshes and National Airport was constructed

Source: Library of Congress, Topography of the federal city, 1791 (by Don Hawkins, 1990)

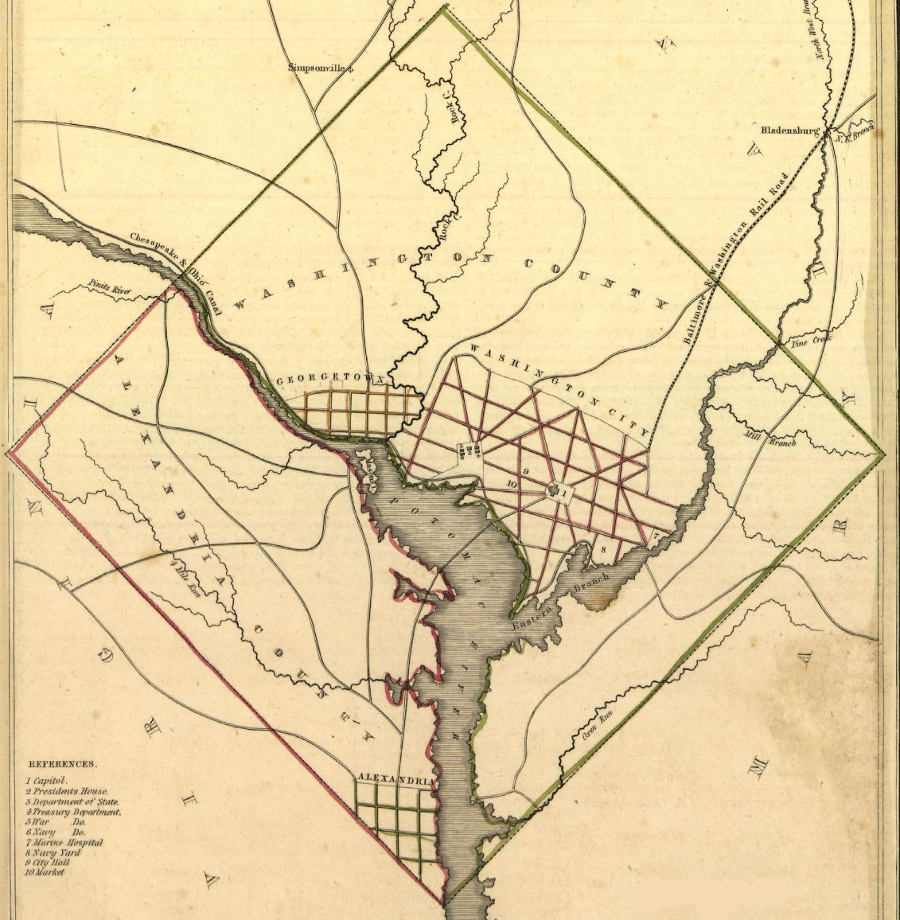

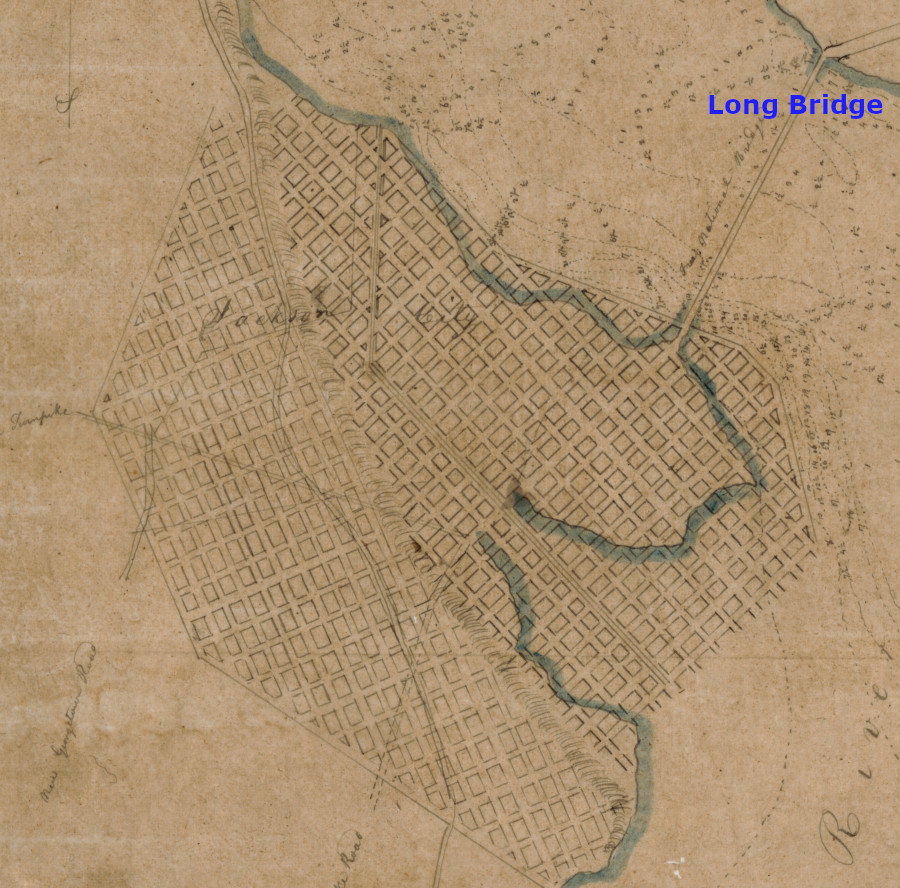

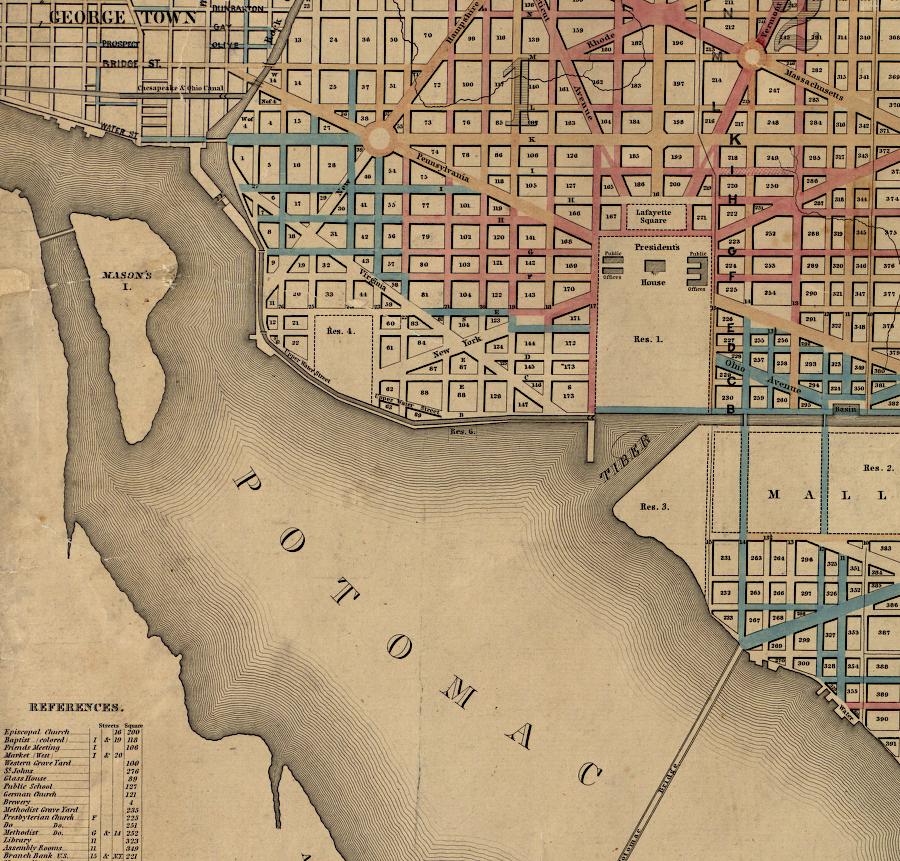

When the first US Congress agreed to move the national capital from Philadelphia to a location on the Potomac River, the new District of Columbia was designed to include 100 square miles of Federal territory. The new District included land on both sides of the Potomac River, plus all of the river where it flowed through the new jurisdiction.

Maryland transferred jurisdiction over its portion of the new District of Columbia, about 67 square miles, to the Federal government on December 19, 1791. In addition to the land, Maryland transferred all of the Potomac River that it owned inside the surveyed square, stretching to the southern edge of the river at the Virginia shoreline.

The Virginia General Assembly agreed to cede over 30 square miles of land to create the District of Columbia in 1789. The state actually transferred the land in 1801, when the Federal government physically moved from Philadelphia.

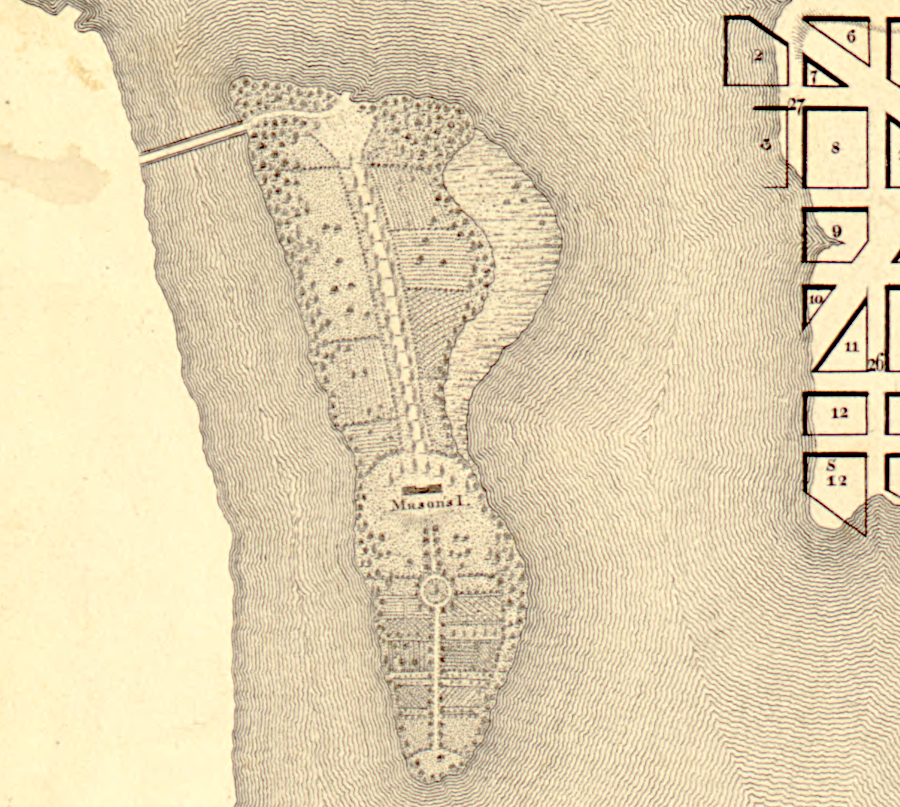

Virginia owned none of the Potomac River after 1632, so Virginia could not transfer any of the Potomac River submerged land or islands to the Federal government in 1801. Title to the islands in the river, including what is now known as Theodore Roosevelt Island, was transferred in 1791 by the Maryland government. Virginia never ceded any of the Potomac River to the Federal government; the colony's right to the river ended in 1632 when Maryland was chartered.2

Because Virginia did not cede its land to the Federal government at the same time as Maryland, the Federal government controlled only 2/3 of the territory that the two states had promised would be given for the new capital between 1791-1801. For that decade, the District of Columbia included only Maryland's cession. Maryland ceded both land and water to the "further Bank of the said River." The southern riverbank, located in Fairfax County, remained part of Virginia until 1801.

The 1791 cession of a slice of Maryland to the Federal government created the first Virginia-District of Columbia boundary. It was located on the southern edge of the Potomac River (not in the middle of the river), stretching north from Jones Point towards Little Falls for roughly 12 miles.

the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary in 1791-1801 was the southern edge of the Potomac River (red line)

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t[he] United States (by Pierre Charles L'Enfant, originally in 1791)

That line was a temporary aberration until 1801. Under the 1790 Residence Act passed by the US Congress, the Potomac River was not intended to define any part of the District of Columbia boundary. Because Virginia and Maryland made their cessions at different times, for a decade a portion of the shoreline stopped being the Virginia-Maryland boundary and became the Virginia-District boundary.

Andrew Ellicott and his team of surveyors, including Benjamin Banneker, never surveyed that shoreline boundary. The survey defining the shape of the District of Columbia cut straight lines through the land of Fairfax County.

the District of Columbia-Virginia boundary that was surveyed as a straight line in 1791 became official only in 1801

Source: Library of Congress, District of Columbia (by Thomas G. Bradford, 1835)

When the Virginia General Assembly ceded its portion of the District to the Federal government in 1801, the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary moved inland from the shoreline. The slice of Virginia that was ceded to the Federal government was organized as Alexandria County within the District of Columbia.

The two straight lines surveyed by Andrew Ellicott and his team, marked by boundary stones of Aquia sandstone each mile, lasted as the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary for 46 years.3

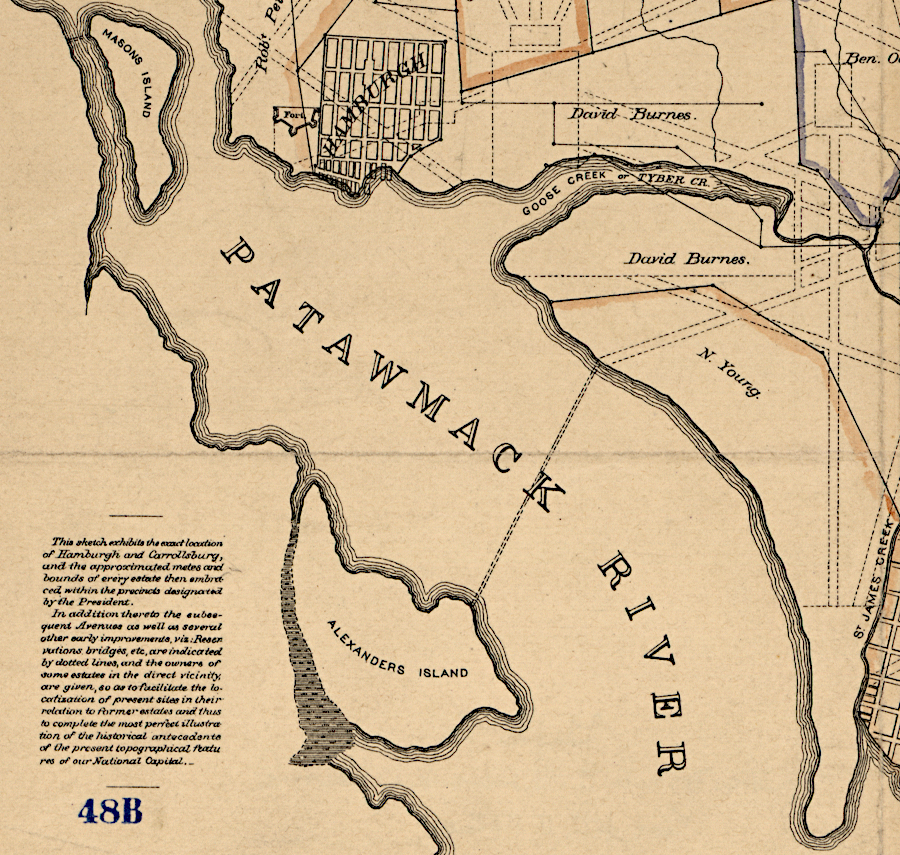

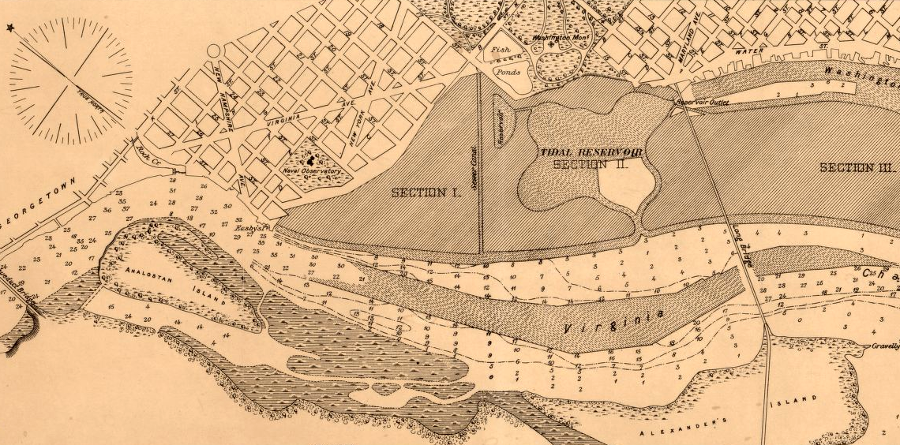

the 1793 mapping by Andrew Ellicott reveals the old mudflats (purple) on the Virginia side of the Potomac River

Source: District of Columbia, The District's Historical Streams

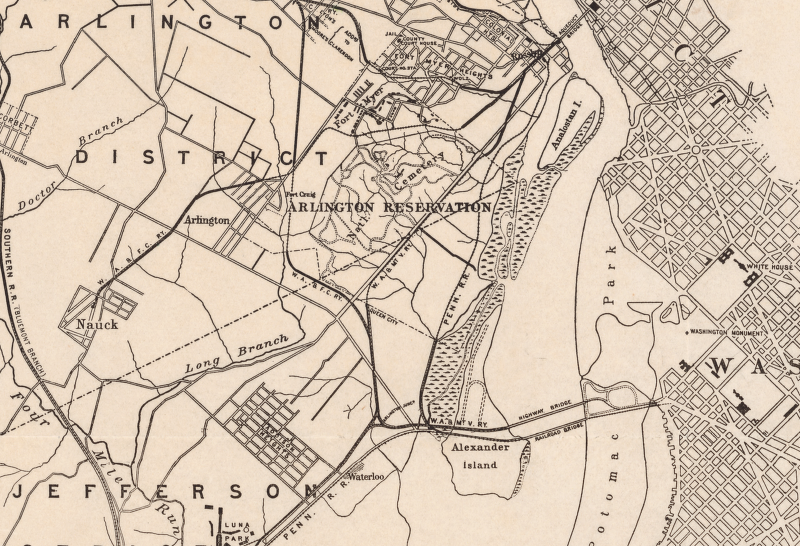

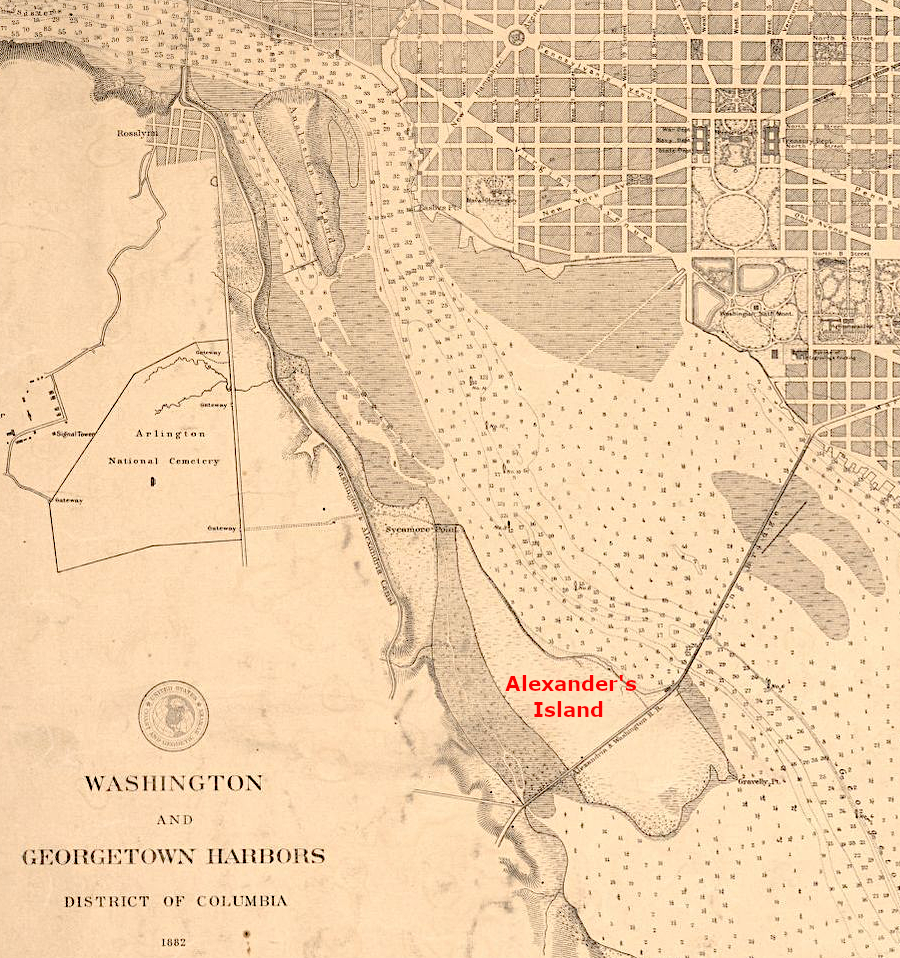

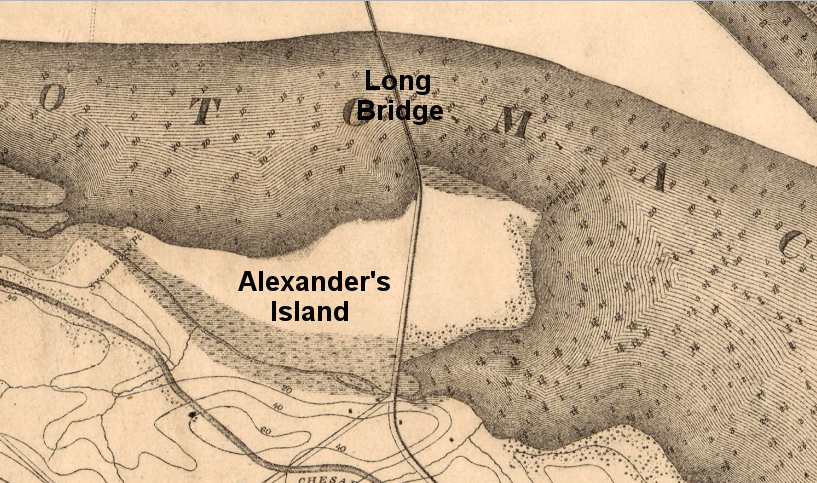

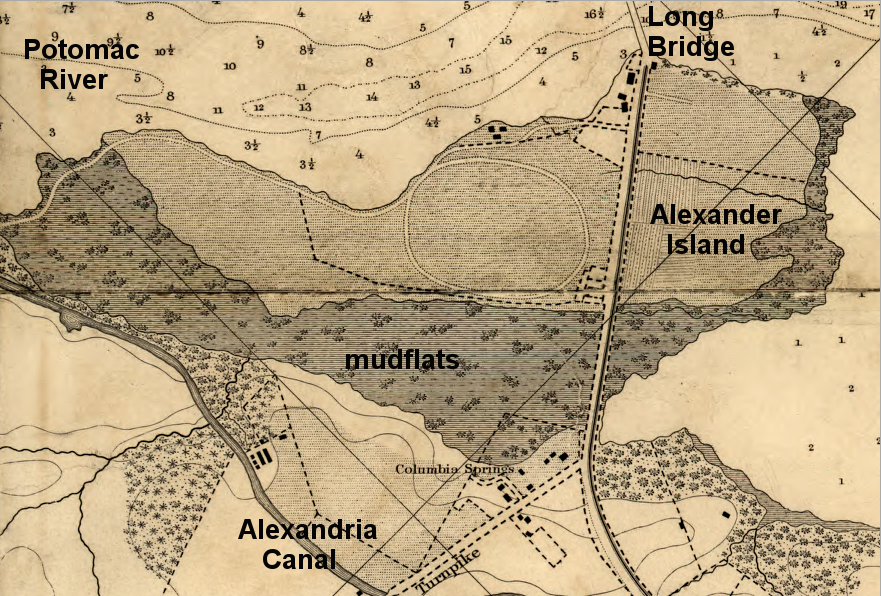

The Federal government made minimal investment in Alexandria County, the portion of the District of Columbia south of the Potomac River. After Long Bridge was rebuilt in 1835, private investors saw an opportunity and tried to start Jackson City at the south end of the bridge on Alexander's Island. The land speculators got President Jackson to lay the cornerstone.

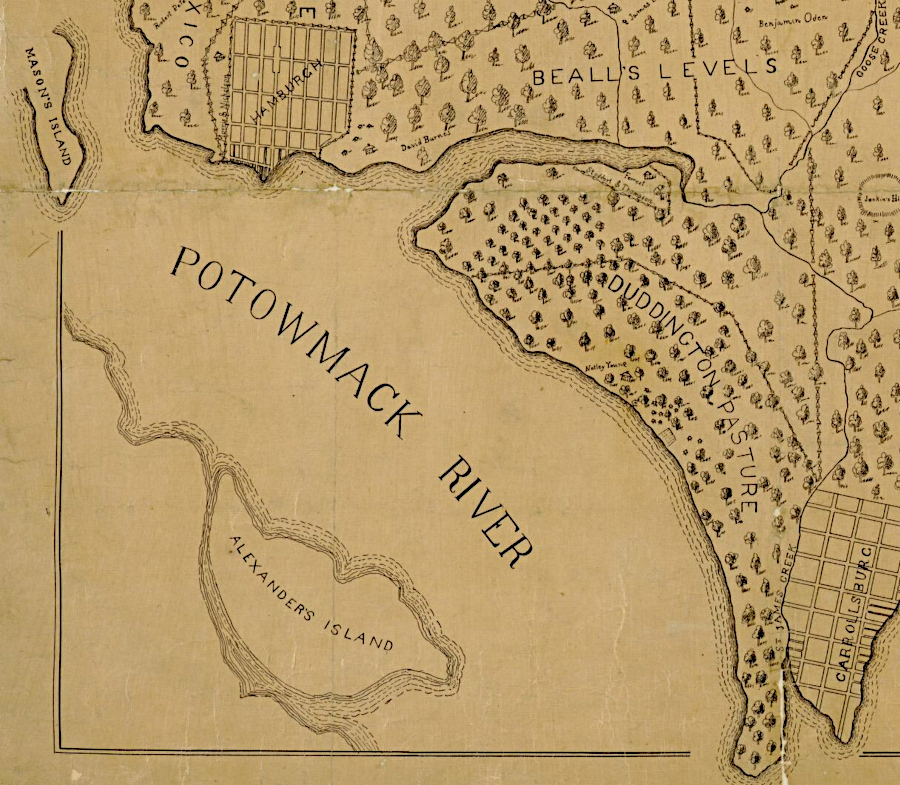

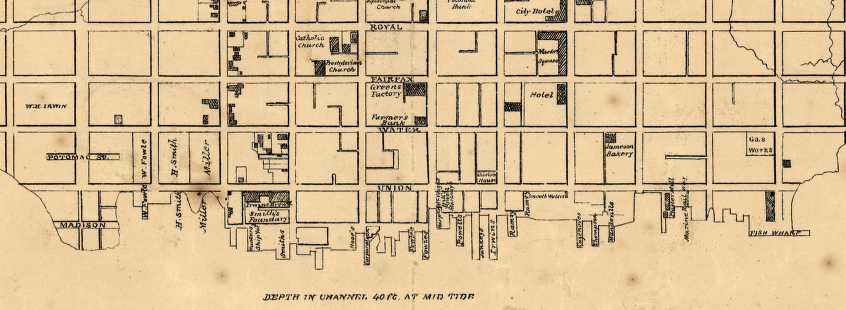

Alexander's Island was separated from the Virginia shoreline by a marsh/mudflat

Source: DC Public Library, Washington and Georgetown harbors: District of Columbia, 1882

The investors, not the Federal government, dredged the mouth of Gravelly Run in hopes of creating a new shipping port upstream of Alexandria. That site is now Roaches Run Bird Sanctuary, next to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport.

Because Alexander's Island was within the boundaries of the District of Columbia in the 1830's, the speculators requested a municipal charter from the US Congress for Jackson City. Two other locations with municipal charters, Alexandria and Georgetown, blocked the effort. They saw Jackson City as competition and derided it as "Humbug City." One of the few successful businesses to develop on Alexander's Island was a watering hole for cattle being driven to slaughter in DC.4

Mason's Island remained in the District of Columbia, but Alexander's Island was retroceded to Virginia in 1847

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of the District of Columbia (1861)

In 1847, the Federal government retroceded the Virginia portion of the District of Columbia back to Virginia. Instead of adding that territory back into Fairfax County, the General Assembly created a new Alexandria County.

As a result of retrocession, the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary reverted back the Virginia-District of Columbia line that had existed between 1791-1801. The Potomac River shoreline of Alexandria County, along the "further Bank" of the river as defined in Maryland's 1632 charter, became the state line again.

Defining the line exactly has never been easy. Legally, the two states and the District of Columbia have debated whether the high water mark or the low water mark defined the boundary. Lawsuits and ultimately an act of Congress eventually defined the location of the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary.

Physically, the natural shoreline of the Potomac River has not been stable. Erosion and accretion of land on the shoreline, and intentional dumping of dirt in Alexandria to expand waterfront land, has affected the location of the shoreline.

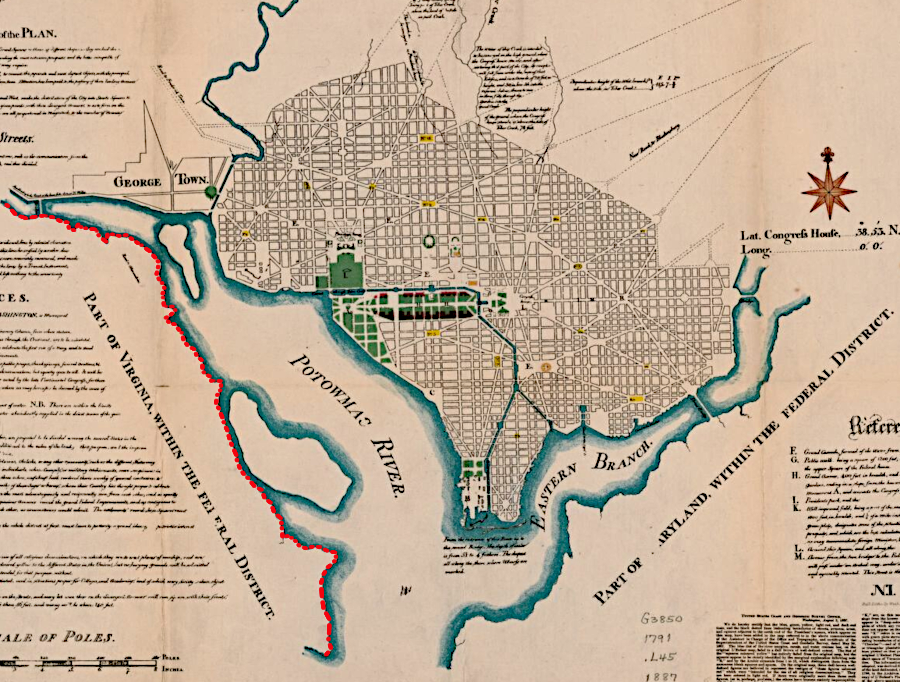

From Alexander Island upstream past Analostan Island, mudflats have grown on the Virginia side of the Potomac River. Much of that physical change was triggered by human action.

Sediment loads in the river increased in the 1700's as forests were cleared for farmland upstream. Massive amounts of silt flowed downstream to the Fall Line. Below Little Falls, the water currents slowed as the river reached sea level. Slower-moving water can hold less sediment in suspension. The silt being carried downstream was deposited on the Potomac River bottom, on each shoreline, and on the islands in the river.

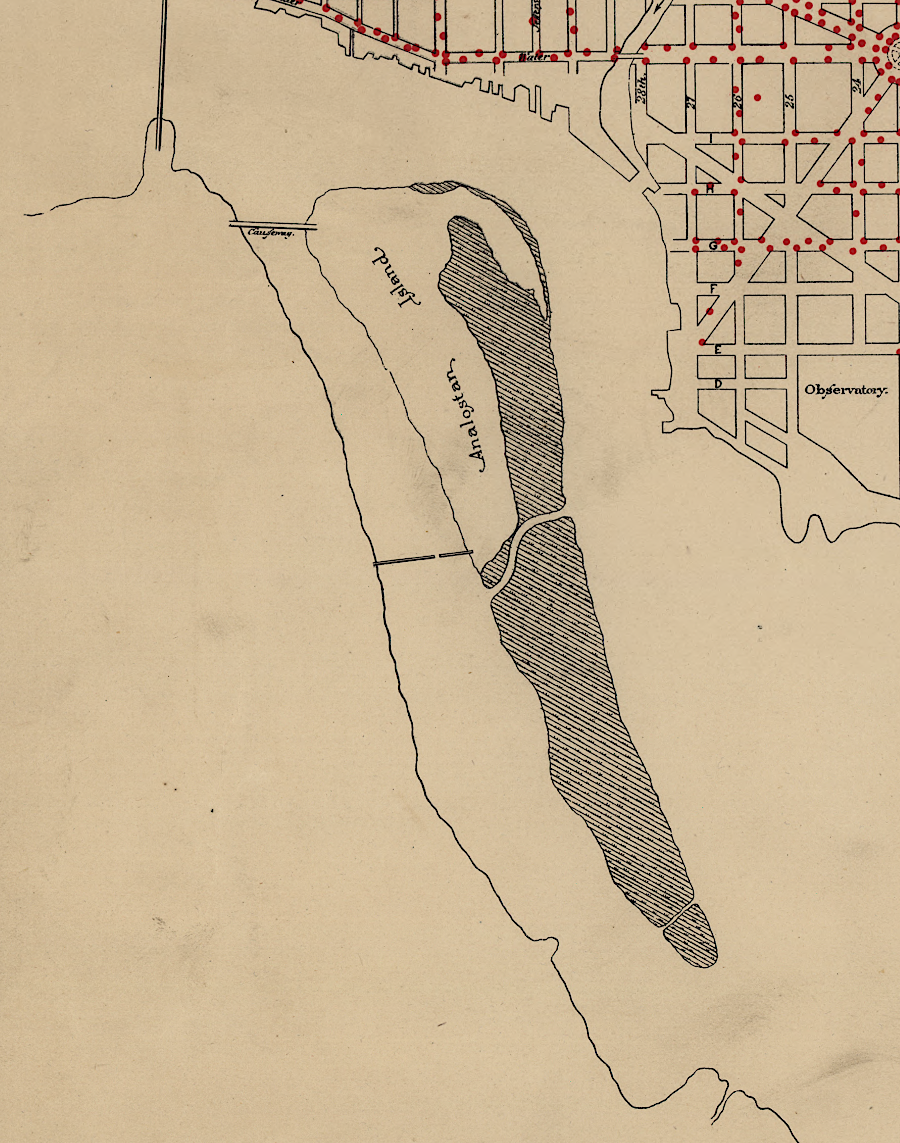

Marshes and mudflats along the Potomac River's Virginia shoreline expanded and diminished as storms brought high water and surges of silt, or washed shoreline sediments further downstream. Analostan Island, known later as Mason's Island and today as Theodore Roosevelt Island, grew on its downstream edge as sediments were added by river currents. Post-Civil War dredging operations later reduced the size and reshaped the island to its current shape.

Upstream of Alexander's Island, the Potomac River naturally carved the deepest channel ("Little River") between Analostan Island and the Virginia shoreline. In 1804, Georgetown officials requested authorization from the US Congress to build a 380-foot long dam/causeway between the southern bank of the Potomac River and Analostan (Mason's) Island.

John Mason, son of George Mason IV, supported the proposal. He had built a home on the island, and a causeway to the Virginia shoreline would allow easy vehicle access to his island. The Mason family had run since 1748 from the Virginia shoreland to Georgetown. The causeway did not hurt his business; people still needed it to get to Georgetown.

mudflats stretched along the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary upstream from Alexander Island

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Alexandria County, Virginia: formerly part of the District of Columbia (1907)

a pre-1900 photo of John Mason's house mistakenly listed it as being in Alexandria County, Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Copy by Historic American Buildings Survey of Dr. Collins Marchall photo

The causeway, creating a dam at the upstream end of the Little River, was designed to force the entire flow of the Potomac River to the other side of Analostan Island next to the port of Georgetown. During a 1794 ice jam, much of the Potomac River had been forced into the Little River channel. That deepened the Little River and made the channel on the Georgetown side more shallow. Georgetown merchants feared that ships would not sail upstream past Alexandria to wharves at Georgetown.

a dam built by 1806 blocked the Little River channel that previously passed between the Virginia shoreline and Analostan (Mason's) Island

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the city of Washington in the District of Columbia (by Robert King, 1818)

A dam forcing all the water to the Georgetown side of the island was expected to scour silt out of the Georgetown Channel. Redirecting the river's flow would boost the economy of Georgetown at the expense of Alexandria on the southern side. The wharves and piers of both Georgetown and Alexandria were within the boundaries of the District of Columbia, but District officials clearly preferred one port city over the other.

The proposal initiated philosophical arguments that the Federal government should not approve the internal improvement, and raised questions regarding its authority to dam the Potomac River. Advocates of a limited Federal government argued that only Maryland and Virginia could authorize blocking the river, under the Compact of 1785 signed by the two states. Those advocates lost the argument.

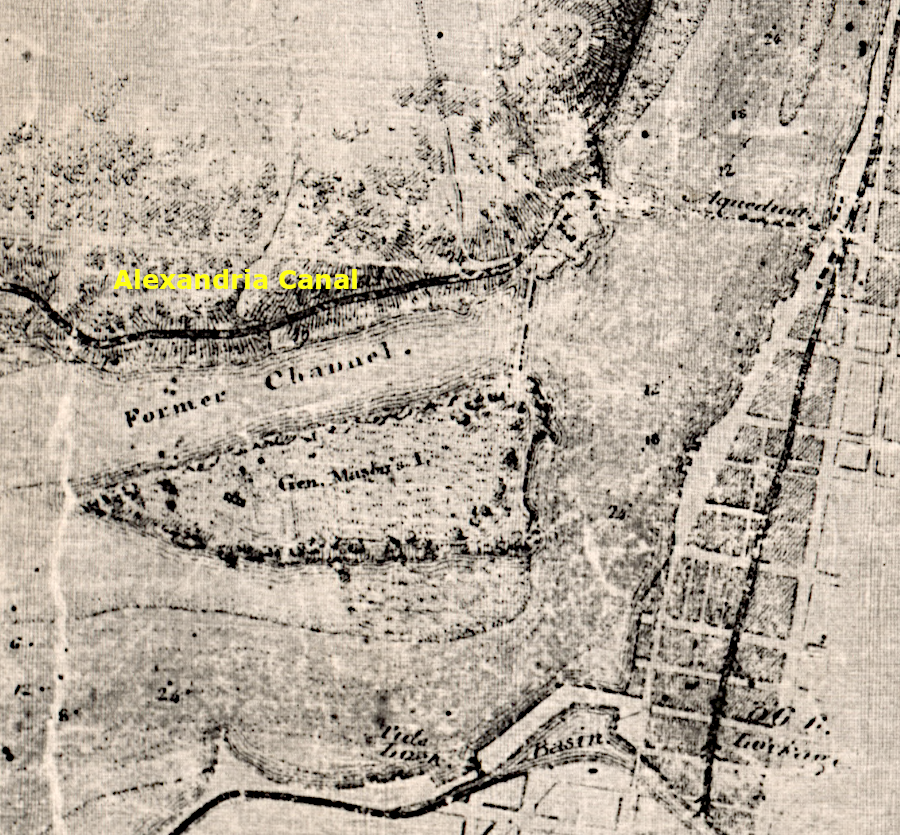

the Alexandria Canal provided access to shipping on the Virginia side of the Potomac River, where a dam blocked the former shipping channel

Source: Library of Congress, Map of part of the Potomac River, from the head of tide water to Alexandria: with its lateral canals, soundings, and topography (1834)

Ten days after the US Congress authorized the dam/causeway, Alexandria supporters proposed building a bridge across the Potomac River at Alexander's Island. The constitutional question over Federal authority had been resolved, and Alexandria's economy would increase if the bridge was completed. It would offset the impact on the city's business by the Chain Bridge upstream, which had diverted the trade of Virginia farmers into Georgetown.

Jackson City was planned to be a city as large as Alexandria

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Jackson City opposite the city of Washington at the south end of the Potomac Free Bridge (1843?)

The causeway barrier began to block the "Virginia Channel" or "Little River Channel" of the Potomac River in 1806, and the former Little River channel filled with silt. New mudflats, upstream and downstream of the dam, connected the southern shoreline with Analostan (Mason's) Island. However, the diverted river flow slowed as it reached sea level downstream of Little Falls. Sediments accumulated in the Washington Channel between Analostan Island and Georgetown; the increased flow in the river did not scour the channel clear. By 1834, the shipping channel to Georgetown was clogged between Rock Creek and the Anacostia River.5

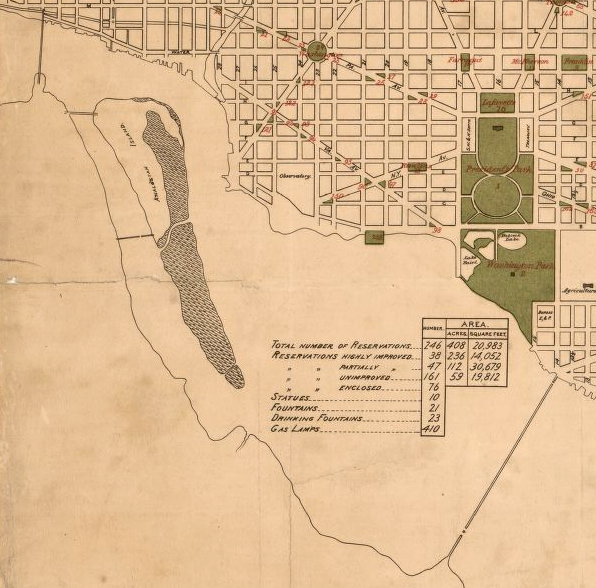

Analostan Island in 1880

Source: Library of Congress, Map No. 5: Gas Lamps (Commissioners of the District of Columbia, 1880)

Before 1847, changes in the shoreline had no impact on the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary. The shoreline on the southern bank was part of the District of Columbia when the dam to Analostan (Mason's) Island was built. The silt was deposited in the river channel below the low-water mark, so mudflats grew in that part of the river which was part of the District of Columbia after 1791.

mudflats grew downstream of Analostan Island

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Washington showing the public reservations under control of the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds (William Forsyth, 1884)

sediments accumulated upstream of the causeway linking the Virginia shoreline to Analostan Island

Source: DC Public Library, Washington and Georgetown harbors: District of Columbia, 1882

The causeway/dam was repaired and modified as needed so it would continue to divert water to the Georgetown side of Analostan (Mason's) Island. After a major flood in 1852, the dam was rebuilt with public funds again.

at the time of the Civil War, silt from Mason's (Analostan) Island stretched downstream towards Alexander Island

Source: Library of Congress, Reconnaissance in advance of Camp Mansfield (186__)

the causeway to Analostan Island was built in 1807

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of the District of Columbia (1861)

The 1852 repair occurred after retrocession of Alexandria County in 1847. The southern bank of the Potomac River had become part of Virginia that year, but the causeway/dam, mudflats, and Analostan (Mason's) Island remained within the District after retroccession.6

silt accumulated above the Analostan Island causeway, and mudflats reached to Alexander's Island in the 1880's

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of the District of Columbia and a portion of Virginia (1884)

After another major flood in 1877, the cost to repair the causeway/dam to Analostan Island was judged excessive and the dam was abandoned. Horses and mules could no longer pull wagons on the causeway from the southern (now Virginia) shoreline into the District of Columbia in order to reach the island.7

Analostan Island was connected in 1806 to the Virginia shoreline by a causeway that blocked river traffic

Source: Library of Congress, Chart of the head of navigation of the Potomac River (1857)

silt deposited at the southern tip has expanded the length of Mason's Island, now called Theodore Roosevelt Island

Source: Library of Congress, Maps of the Washington Aqueduct, Md. and Washington D.C (1864)

No one proposed any shoreline development that required clarifying if the boundary was the high-water mark or the low-water mark on the Virginia shoreline until after the Civil War, when the US Congress outlawed gambling in the District of Columbia. The gamblers moved their operations to Jackson City on Alexander's Island at the south end of Long Bridge. The jurisdiction responsible for Jackson City was vague after the Alexandria County portion of the District of Columbia was retroceded to Virginia. At low tide, the "island" was connected to the Virginia shoreline.

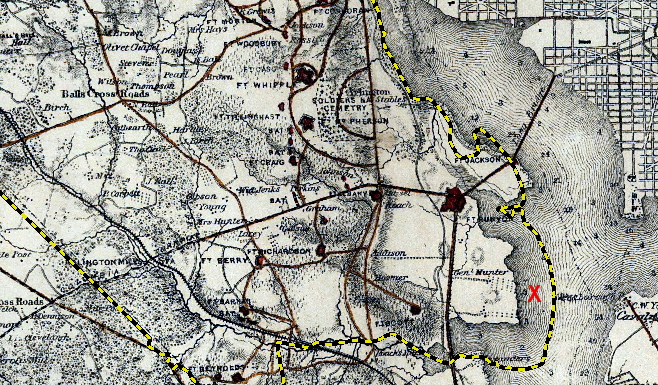

during the Civil War, Fort Jackson was named after Jackson City (where Long Bridge terminated on Alexander Island)

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Alexandria, Virginia (by Robert Knox Sneden, 1861-65)

Jackson City began to grow in the 1870's. Virginia officials were more accommodating than the District of Columbia to gambling and prostitution, and more corrupt. Gambling interests claimed that Jackson City had become part of Virginia after the 1847 retrocession.

Alexander's Island was separated by marsh/mudflat from the Virginia shoreline, but it was not part of Maryland and not in that state's cession in 1792

Source: Library of Congress, View of the city of Washington in 1792

in 1792, Alexander's Island could be considered part of the Virginia shoreline due to marsh and mudflat connections

Source: Library of Congress, Sketch of Washington in embryo: viz., previous to its survey by Major L'Enfant, 1792 (Capitol Centennial Committee, 1893)

Since the creation of the District of Columbia, sediments had expanded the mudflat which linked Alexander's Island to the southern bank of the Potomac River. By the 1870's the mudflat was clearly above the high-water mark. If the Virginia shoreline incorporated the island, then the ban on gambling within the District of Columbia did not apply to Jackson City, Virginia.

Alexander's Island around 1837, with Long Bridge crossing the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Chart of the Potomac River and Eastern Branch from the Sister Islands to Geesboro Point and thence to the Navy Yard Bridge (by Maskell C. Ewing, 1837?)

Potomac River shoreline in 1841

Source: Library of Congress, Chart of the head of navigation of the Potomac River shewing the route of the Alexandria Canal

sediments accumulated below Analostan Island after construction of the causeway blocked water flow into the Little River channel

Source: Library of Congress, Hydrographic map of the Potomac River from Aqueduct Bridge, Georgetown, to Long Bridge, Washington, D.C. (1871)

a marsh bordered the west side of Alexander's Island in 1882, and the location of the Virginia shoreline was a judgment call

Source: Library of Congress, Washington and Georgetown harbors, District of Columbia (US Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1882)

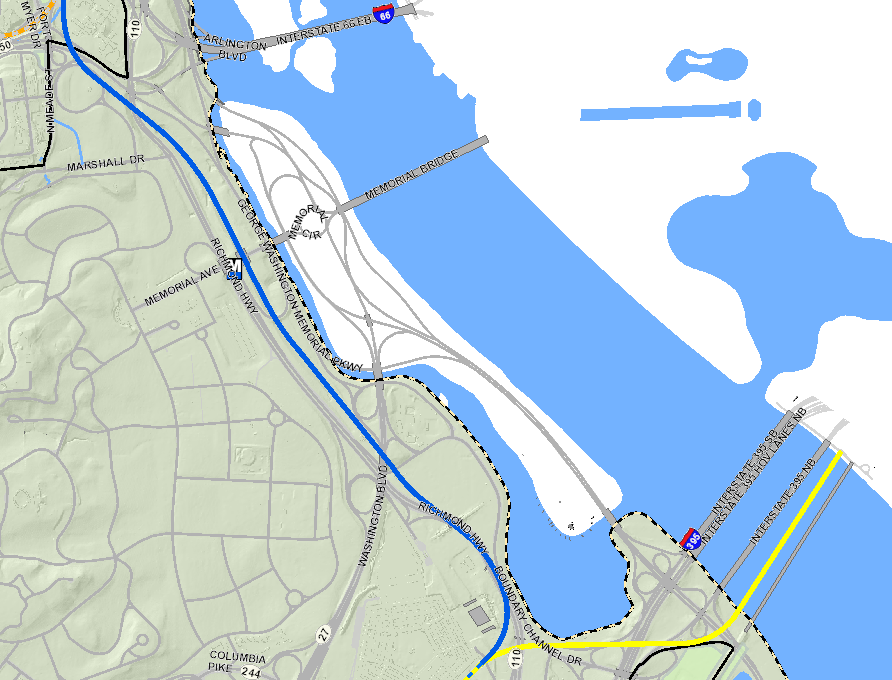

the shoreline has been transformed, but the District of Columbia still extends to the high-water mark on the western edge of the Boundary Channel

Source: Arlington County, AC Maps

Responsibility for Jackson City could have been disputed, but there were no strong reasons for District officials to claim ownership of the land at the south end of Long Bridge. Pushing the gambling to the other side of the river had moved the prostitution and drunken behavior away from the neighborhoods near Capitol Hill. There was no economic incentive for the District to desire control of Alexander's Island, and District officials were willing to let Alexandria County officials be responsible for the law enforcement headaches there.

after 1847, Jackson City on Alexander Island was in Virginia and not the District of Columbia

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Potomac River, West Shore, Alexandria and Arlington Counties, VA

the US Geological Survey considered Alexander Island to be part of Virginia, not the District of Columbia, in 1900

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Washington-MD quadrangle (1:62,500 scale) (1900)

The owners of the gambling operations claimed a legal presence in Virginia, but did not comply with the state's racial segregation laws. Black and white customers were equally welcome in gambling houses that attracted 2,000 visitors per day. Everyone's money was welcome.

A racetrack operated on Alexander Island between 1894-1897, and betting on horses was just one of the vices in the area. Farmers bringing crops to Alexandria traveled through the future area of Rosslyn and the Pentagon in groups rather than alone, because they needed protection against robbery.

When Virginia banned horseracing in 1897, the track closed in compliance with state law. There was no attempt to claim the track was in the District of Columbia, in part because running actual races was not especially profitable.

The operators did retain their "poolroom" operations. Those allowed customers to bet on races in other cities via telegraph reports. Interstate gambling was not legal, but corrupt local officials in Alexandria County facilitated it. Though customers came from the District of Columbia, the Jackson City poolrooms were outside its jurisdiction.

In 1903, Crandall Mackey won election as Commonwealth's Attorney for Alexandria County. He went on a crusade to close down illegal gambling operations.

Mackey organized posses of citizens, since so many of the sheriff's deputies were associated with the criminals of Jackson City and Rosslyn rather than reliable allies. The new Commonwealth's Attorney led raids on the gambling dens and houses of prostitution, destroying much property. That approach, while questionable legally, was more effective than relying upon the judicial process of the local court system.8

In response, the Jackson City gaming operators claimed that their poolrooms and saloons were not located in Virginia. They argued that the 1847 retrocession was not constitutional. If they won that argument, then a Commonwealth's Attorney elected in Virginia could not interfere with poolrooms located in the District of Columbia. A Federal judge rejected that argument, enabling Crandal Mackey to continue his brazen enforcement.9

Alexander Island and Jackson City were in Virginia, after retrocession in 1847

Source: Library of Congress, Sketch of the seat of war in Alexandria & Fairfax Cos. (1861)

The first attempt to clarify the exact location of the "further Bank of the said River" was in 1877. Virginia and Maryland wanted to resolve which state owned valuable oyster beds in the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River downstream from the District of Columbia.

The two states negotiated a deal and arbitrators established the low-water mark of the Potomac River's southern shoreline as the Maryland-Virginia boundary. For centuries, Virginians had used the land between the high-water and the low-water mark. The arbitrators made official that the low-water mark along the Potomac River was the boundary between the two states, based on the prescriptive use.

However, the District of Columbia was not included in the 1877 Black-Jenkins award (which the US Congress ratified in 1879). The arbitrators were resolving a Virginia-Maryland dispute and had no authority to define the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary. After the Black-Jenkins Award, Virginia and Maryland completed a survey to define a fixed boundary, going from headland to headland, along the Potomac River. That survey started at Jones Point and went downstream, but the fized boundary was not extended upstream into the District of Columbia.

Disputes regarding the ownership of the riverbed on the northern shoreline of the Potomac River finally led to key legal decisions affecting the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary on the southern shoreline.

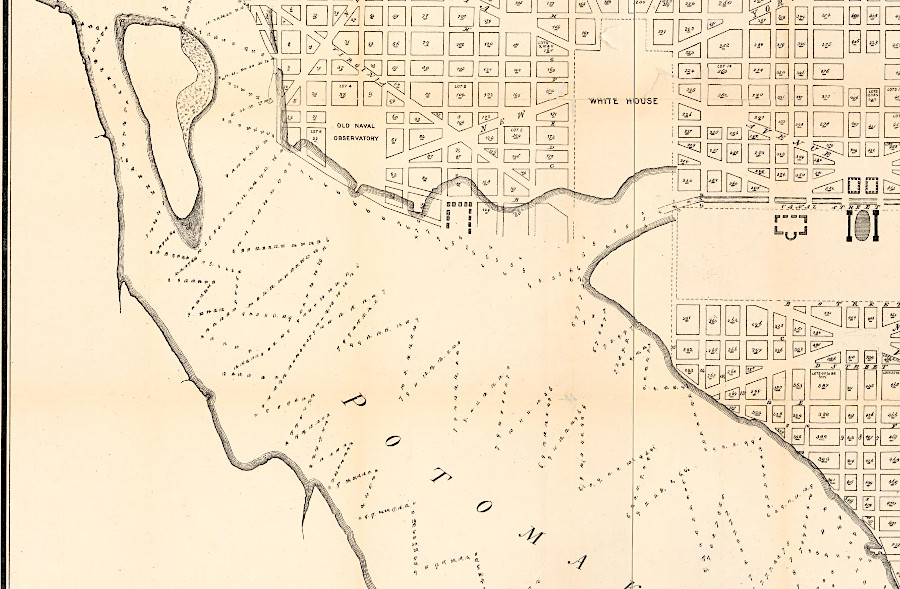

north bank of the Potomac River, as George Washington saw it in the 1790's

Source: Library of Congress, The Dermott or tin case map of Washington 1797-8.

On the north bank, sediments washing down the Potomac River had accumulated downstream of the Fall Line. The speed of the river dropped as the stream gradient flattened, the river channel widened, and tides pushed against the river flow twice a day.

The sediment accumulation at tidewater created new "made land" from Analostan Island downstream Seeing an opportunity, a resident of Georgetown named John L. Kidwell obtained a patent from the General Land Office for the new land on the northern bank. The land was clearly within the District of Columbia, but who owned the accreted mudflats was not clear. Different land speculators also claimed to own the empty land that became known as Kidwell Meadows, and later as Potomac Flats.

Kidwell Meadows/Potomac Flats was created by sediment washing down the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Location map of Kidwell's Meadows in the Potomac River estuary, Washington D.C. (188_)

sediments clogged the river channel and settled on the Potomac Flats

Source: Library of Congress, Hydrographic map of the Potomac River from Aqueduct Bridge, Georgetown, to Long Bridge, Washington, D.C (by William P. Craghill, 1871)

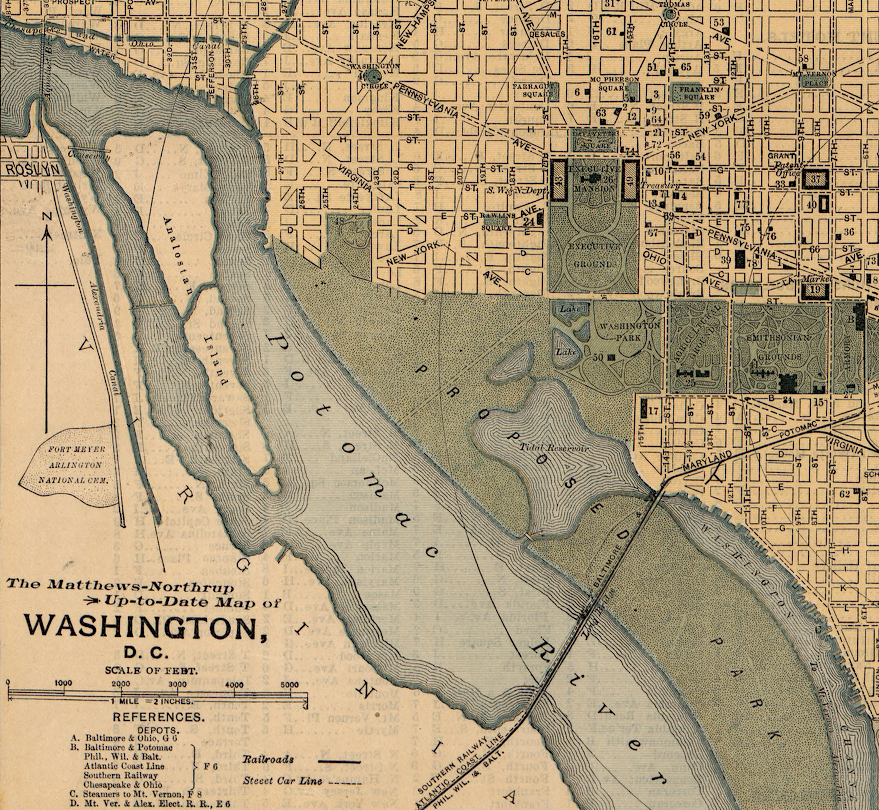

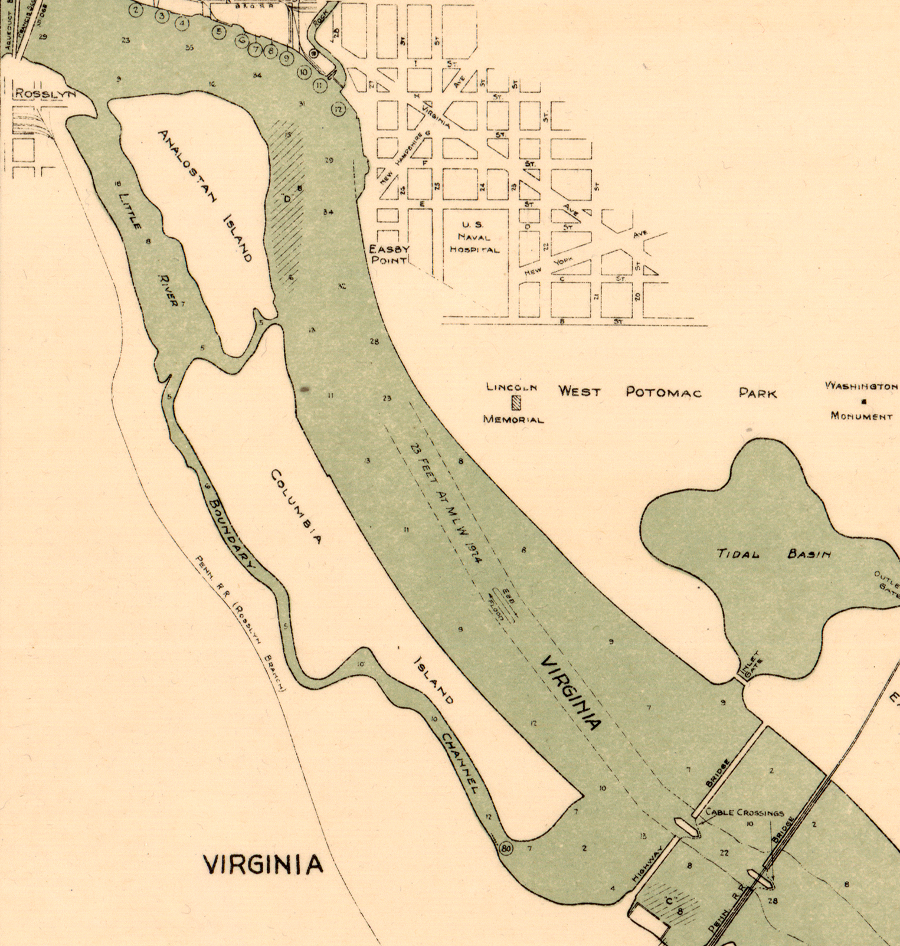

After major floods in 1877, 1881, and 1889, the US Army Corps of Engineers dredged the shipping channels on the northern side of the Potomac River leading to Georgetown. Most of the dredged material was dumped on the northern bank. The dredge spoils filled the Potomac Flats and created the land later used for the Lincoln Memorial, Jefferson Memorial, Tidal Basin, East Potomac Park, and West Potomac Park.

the northern bank of the Potomac River was expanded by depositing dredge spoils to create land later used for parks and monuments

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington, including the county of Montgomery, Maryland (by Griffith Morgan Hopkins Jr., 1879)

the Lincoln Memorial was built on marshland that is now the Reflecting Pool

Source: Library of Congress, Lincoln Memorial with marsh in foreground (ca. 1917)

Major Peter C. Hains was assigned the job of dredging the shipping channel upstream between 17th Street to Georgetown. Those spoils also were deposited on the tidal flats, with retaining walls to minimize the sediment washing back into the channel.

Some dredge spoils from the river bottom, plus some fill dirt from construction projects in the District, were dumped in the marshes along the Virginia shoreline. The dredging and filling operations obscured the location of the historic 1801 shoreline, which defined the legal boundary between Virginia and the District of Columbia.

Hains designed the Tidal Basin so lakes would capture water at high tide and release it at low tide, in order to flush out the modern Washington Channel in front of the Wharf District. Today the Tidal Basin, completed in 1897, floods regularly for two reasons. The fill material used to create the Tidal Basin and the western end of the National Mall has compressed and sunk three feet, while sea level has risen another foot.

most dredge spoils from the Georgetown Channel were deposited on the north bank of the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Potomac River at Washington, D.C., map showing progress of work: June 30, 1890

when mudflats along the Virginia shoreline were converted to dry land, the old shoreline remained the boundary between Virginia and the District

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of the District of Columbia (1861)

Hains was delayed in his ability to dump dredge spoils on Kidwell Meadows until ownership of the land reached a final court decision. In 1899, the US Supreme Court ruled in Morris vs. United States that the Federal government retained control of the riverbed. The ownership boundary on the northern shore did not change as the dredge spoils converted marsh/water into dry land.10

the northern shoreline of the Potomac River before dredging and filling

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Washington D.C. showing wood, concrete, and stone street pavements (by William James Stone, 1873)

the northern shoreline of the Potomac River was dramatically altered by dredging and filling

Source: Library of Congress, The Matthews-Northrup up-to-date map of Washington, D.C (1897)

In 1920, Alexandria County was renamed Arlington County. The change in name had no impact on the location of the county's boundary with the District of Columbia. Similarly, Alexandria's expansion in 1915 and its 1929 annexation of the land from First Street to Four Mile Run changed the jurisdiction on the Virginia side of the boundary with the District of Columbia - but had no effect on the location of the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary. The boundary confusion in Arlington County remained the same as the confusion had been in Alexandria County.

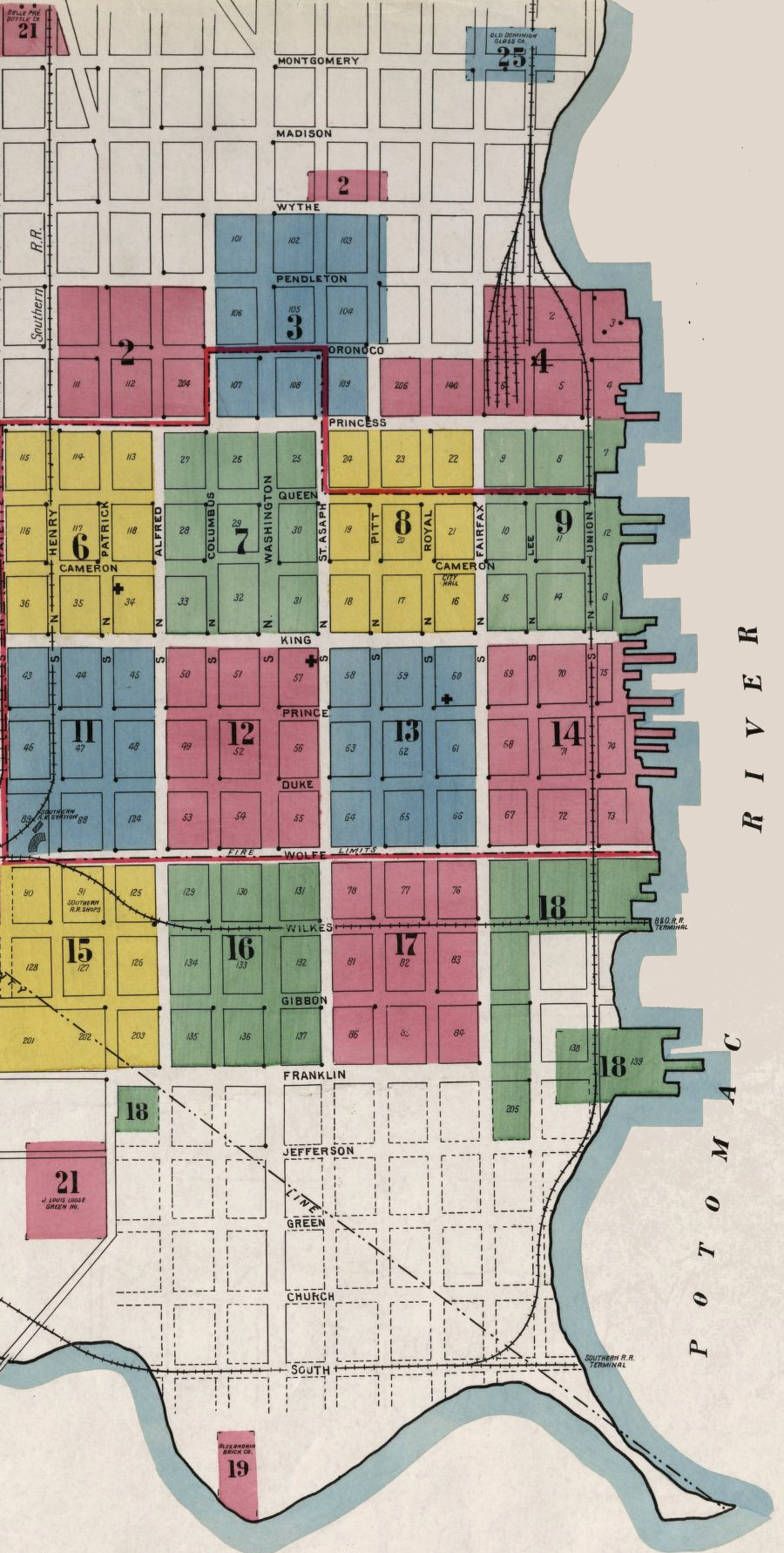

in 1923, Alexandria's boundary on the Potomac River waterfront stopped at First Street and did not extend to Four Mile Run

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1921 in the Marine Railway & Coal Co. vs US vase, the US Supreme Court resolved ownership of land on the Alexandria waterfront which had been created by dredging and filling, most recently in 1910-1912. Similar to the case decided in Morris vs. United States, the owner of land on the riverfront claimed the new land by asserting riparian rights.

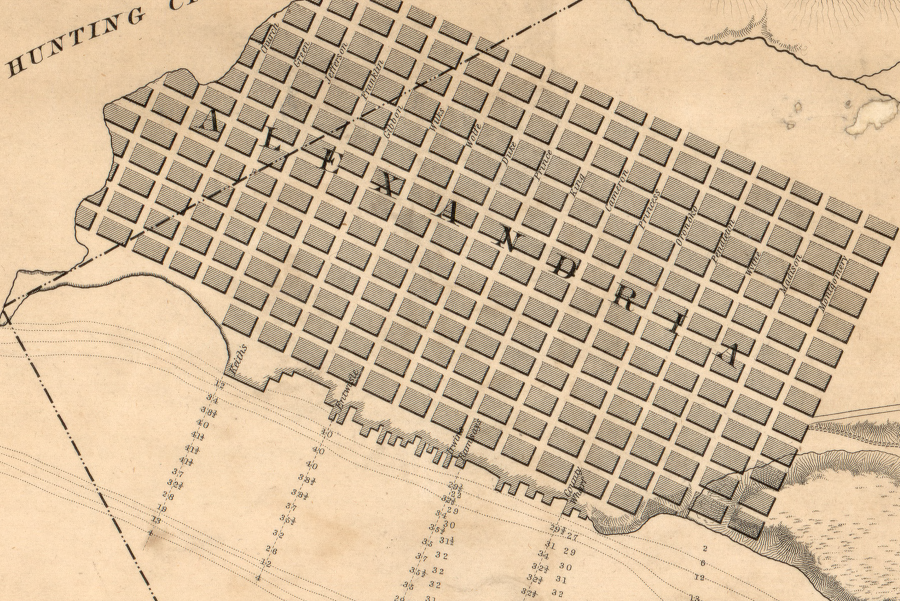

The Alexandria waterfront had been expanded by shoreline owners into the Potomac River. In 1760, trustees of Alexandria had authorized all owners of riverfront lots to build individual wharves.11

the deep shipping channel in the Potomac River is adjacent to the Alexandria waterfront

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Starting in colonial times, piers were built outwards into the river and earth from the city was dumped between the docks to create new land for wharves and warehouses. Old ships were also used as "fill" to create valuable new land. Then new docks were constructed on the new shoreline, extending out into the river channel again. Filling the spaces between piers with dirt created more waterfront land for wharves and warehouses.

docks were built into the river from the shoreline, then the spaces between the docks were filled in

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the city of Washington in the District of Columbia (William Forsyth, 1870)

As the Alexandria waterfront expanded into the Potomac River, the location of the "further Bank" was literally buried. By the time of retrocession in 1847, the edge of the Potomac River was one or two blocks inland from the 1791 shoreline compared when Maryland ceded its territory.

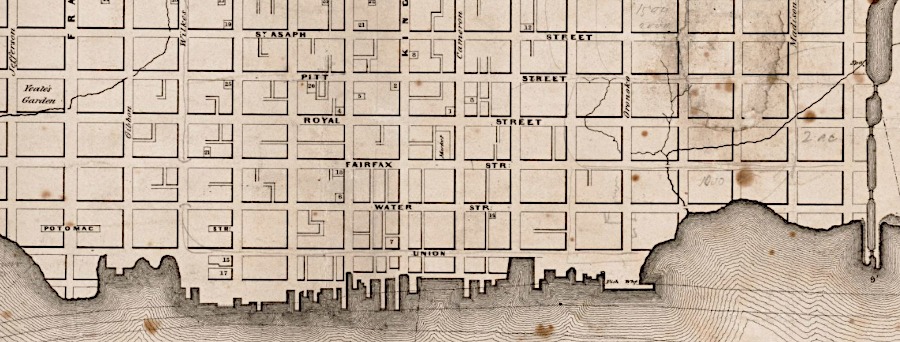

in 1749, the Alexandria waterfront stopped at what became Water Street

Source: Library of Congress, Plat of the land where on stands the town of Alexandria; A plan of Alexandria, now Belhaven (derived or copied by George Washington, 1749)

the Alexandria waterfront was enlarged first by constructing wharves (shown in orange), then filling in between the wharves with dirt (shown in red and green)

Source: Office of Historic Alexandria/ Alexandria Archaeology, Traveler's Accounts of the Historic Alexandria Waterfront (p.12)

construction of wharves created the jagged edge of the Alexandria waterfront in 1841

Source: Library of Congress, Chart of the head of navigation of the Potomac River shewing the route of the Alexandria Canal (1841)

by 1845, wharves (blue) stretched far beyond the 1791 Alexandria shoreline (red)

Source: City of Alexandria, Historic Wharves Map

by 1862, the Alexandria waterfront had expanded 1-2 blocks past the 1791 shoreline

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of Alexandria (1862)

By filling between the piers and altering the shoreline, merchants and shippers moved the edge of the Potomac River from the base of Carlyle House (modern Lee Street) to its present location. At least 10 new city blocks were created by expanding into the river.

wharves on the Alexandria waterfront during the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, View from Pioneer Mill, looking up the wharf

One ship used as fill at Point Lumley around 1800 was excavated in 2016 during construction of the Hotel Indigo at Duke and South Union streets. Archeologists found three more in 2018 at the corner of Duke and South Union streets, as construction replaced Robinson Terminal South warehouses with new townhouses as condominiums.

The ship discovered during construction of Hotel Indigo was treated at the Conservation Research Laboratory at Texas A&M University so it could be exhibited publicly. The other tree ships were placed in a pond at Ben Brenman Park to keep the wooden timbers wet, preventing what would otherwise be rapid decay by wood-destroying fungi.

As noted by the Office of Historic Alexandria:12

in 2016, excavation to build a new hotel on the waterfront revealed the remains of a ship that had been scuttled in the late 1700's to extend the shoreline beyond the natural low water mark

Source: City of Alexandria, Nautical Discoveries at 220 South Union Street

ships from the 1700's were excavated from 15 feet underground during 2016-18 construction projects on the Alexandria waterfront

Source: GoogleMaps

Using ships and other fill to create new land changed the Potomac River shoreline. The Supreme Court ruled again on the location of the District of Columbia-Virginia boundary in 1922. The Federal government had deposited dredge spoils on the Alexandria side of rip-rap along the shoreline, then claimed ownership of the "made land" and fenced it off. The adjacent Marine Railway & Coal Company tore down the fence and claimed ownership of the land.

The US Supreme Court ruled in Marine Railway & Coal Co., Inc. v. United States that the title of the United States embraced the whole river bed, that the Black-Jenkins award did not affect the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary, and that:13

In 1922, the Court of Appeals (District of Columbia Circuit) heard a case involving a fisherman who stood on the Virginia shoreline. He stepped out on rocks jutting into the Potomac River above Chain Bridge and, using a 20-foot long pole, dipped a net into the Potomac River between the high-water and low-water mark. Fishing with a dip net violated the laws of the District, and he was indicted by a grand jury there.

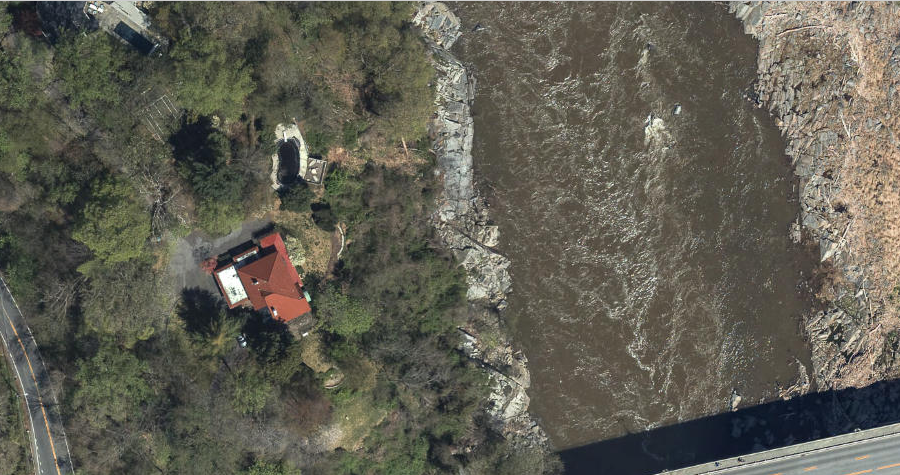

a court ruled in 1922 that dip-netting from rocks extending out from the Virginia shoreline would cross into the District of Columbia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Federal court ruled in Herald v. United States that the angler was in the District of Columbia, even though he was above the low-water mark. The high-water mark on the south bank of the Potomac River was the boundary. The court determined that the 1785 compact between Virginia-Maryland had no effect within the District of Columbia, because Maryland and Virginia had ceded all rights when the Federal district was created.

The 1877 Black-Jenkins award decision that fixed the Maryland-Virginia boundary at the low-water mark also had no effect within the boundaries of the District. That deal between Maryland and Virginia, in which Virginia acquired prescriptive rights to the low-water line, did not affect the separate District of Columbia-Virginia boundary.14

mudflats lined the southern bank of the Potomac River, from Analostan/Mason's Island to Alexander Island

Source: Library of Congress, Potomac River at Washington D.C., plan showing how reclaimed area may be utilized (1894)

southern bank of the Potomac River, from Analostan/Mason's Island to Alexander Island today

Source: GoogleMaps

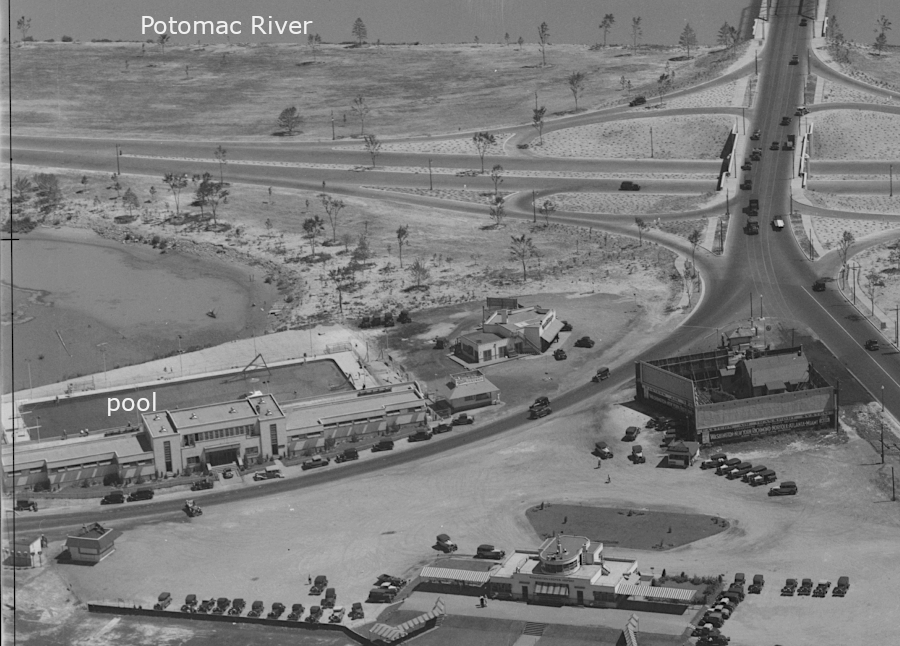

in 1932, the pool at Washington Airport was in Virginia, above the high-water mark

Source: Library of Congress, Aerial View Of South End Of Highway Bridge, 14th Street Underpass Looking Northeast, 1932

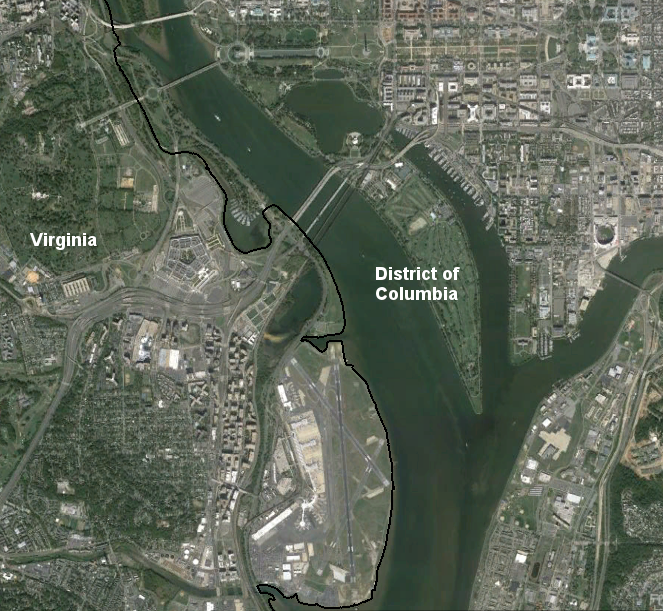

Columbia Island near the Pentagon is not within the boundaries of Virginia. The island evolved as sediments accumulated naturally off the southern tip of Analostan Island. Dredge spoils used to construct the island were placed below the high-water mark of the shoreline starting around 1915, so the newly-created land was located within the District.

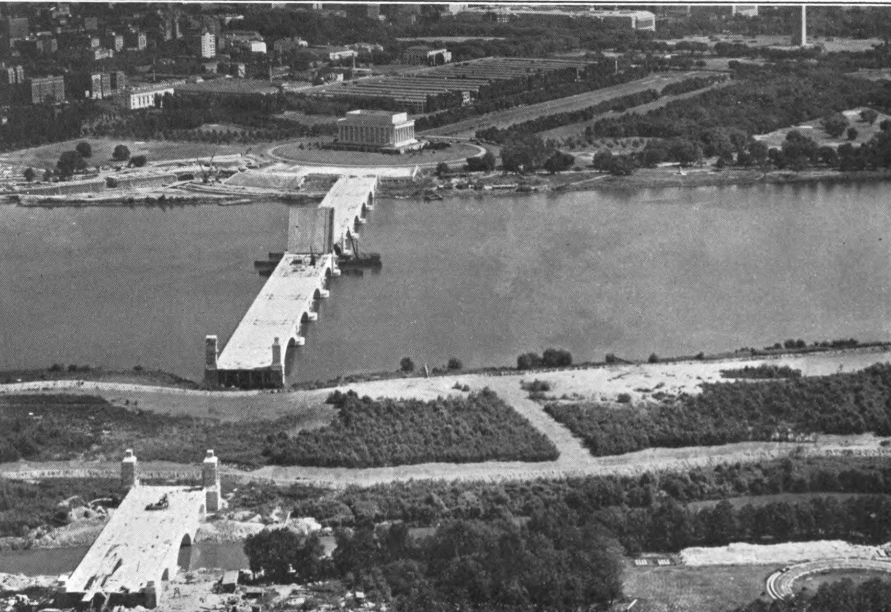

Planned construction of the Memorial Bridge led to major modification of the island starting in 1923. The Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission arranged with the US Army Corps of Engineers for the shipping channel to be relocated from near the northern shoreline to the middle of the river. That facilitated construction of a bridge in the Neoclassical style, with the drawbridge in the center of the Potomac River.

The sediments excavated from the bed of the Potomac River, plus some solid rock blasted out of the new channel, were deposited on Columbia Island between 1925-27. Dredge spoils increased the height of the island by an additional 8 to 13 feet, raising it to 20 feet above mean low water. The transformation of Columbia Island from piled-up dredge spoils to the version seen today was completed as part of the Arlington Memorial Bridge project.

To ensure floodwaters could pass on either side of the bridge piers, 40 acres of land were "amputated" from Columbia Island. That created a wider gap between Columbia Island and Analostan (now Roosevelt) Island. Construction of Columbia Island and Boundary Channel further obscured the historic location of the 1791 shoreline that defined the Virginia-Maryland boundary, which the District of Columbia had inherited.

the gap between Columbia Island and Analostan Island was increased to allow Potomac River floodwaters to pass downstream

Source: Library of Congress, Aerial photographic mosaic map of Washington, D.C. (1922) and Photographic mosaic map, Washington, D.C. (US Army Air Corps, 1928)

In 1930, the shoreline downstream from Georgetown was dredged again to improve the shipping channel. Those spoils were pumped across the river to raise Columbia Island to 20' in height, enabling creation of parkland comparable to East Potomac Park.15

in 1923, Columbia Island was almost connected to Analostan (now Roosevelt) Island

Source: Library of Congress, Port facilities at Washington D.C. & Alexandria, Va (Corps of Engineers, 1923)

the elevation of Columbia Island was raised in the 1920's, using dredge spoils from the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Public buildings and public parks in the District of Columbia: under the jurisdiction of the director (1932)

Arlington Memorial Bridge was constructed across Columbia Island

Source: Hathi Trust, Annual report of the Director of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital, 1930

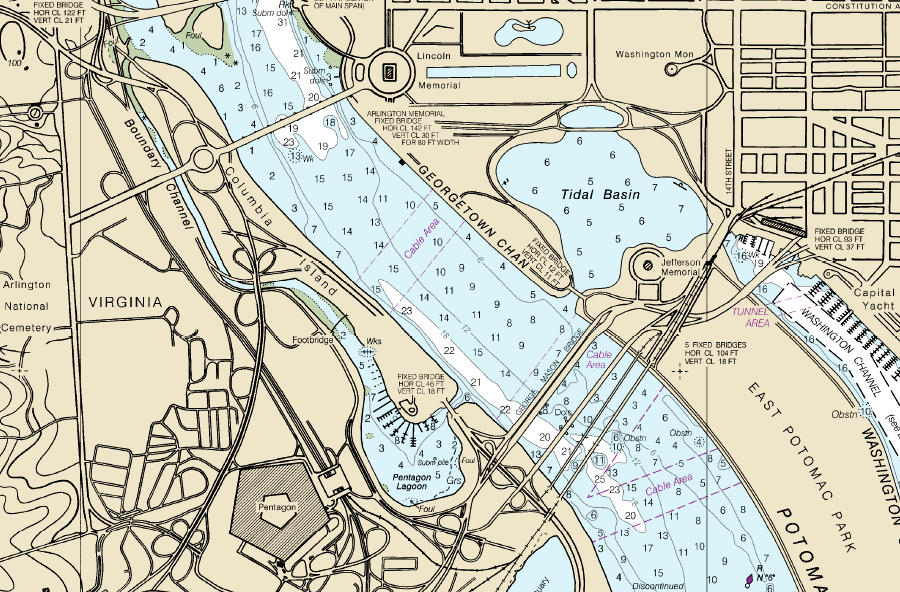

Boundary Channel was created by dredging the Potomac River and depositing spoils on Columbia Island between 1911-1927

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Coast Survey Chart 12289

A 1931 lawsuit over the submerged gravel in the Potomac River led to a US Supreme Court decision clarifying where the District of Columbia ended and Virginia began.

In the mid-1920's, Hoover Field and then Washington-Hoover Airport were constructed on the flat land near the Virginia end of the 14th Street Bridge (site of the Long Bridge during the Civil War). Washington-Hoover Airport was expanded into the Potomac River by depositing earth excavated for construction of the buildings at Federal Triangle and other sites across the District. The former mudflats were raised up, and at the time the airport assumed it owned the new land created by the fill dirt.16

The Federal government contracted with Smoot Sand and Gravel Co. to build a retaining wall on the shoreline. That project was part of the construction of the Mount Vernon Memorial Highway, connecting Arlington Cemetery/Memorial Bridge to Mount Vernon in advance of the 200th anniversary of George Washington's birth in 1932.

The airport objected to the wall and claimed ownership of the land once located below the high-water mark. The owners of the private airport lost the case. In 1931 the US Supreme Court ruled, in Smoot Sand & Gravel Corp. v. Washington Airport, Inc., that the Virginia-District boundary was the high-water line on the Potomac River. All the land below the high-water mark belonged to the District.17

As a result, The Virginia-District of Columbia line upstream from Alexandria follows the meandering high-water line, which the US Coast and Geodetic Survey surveyed in 1947.18

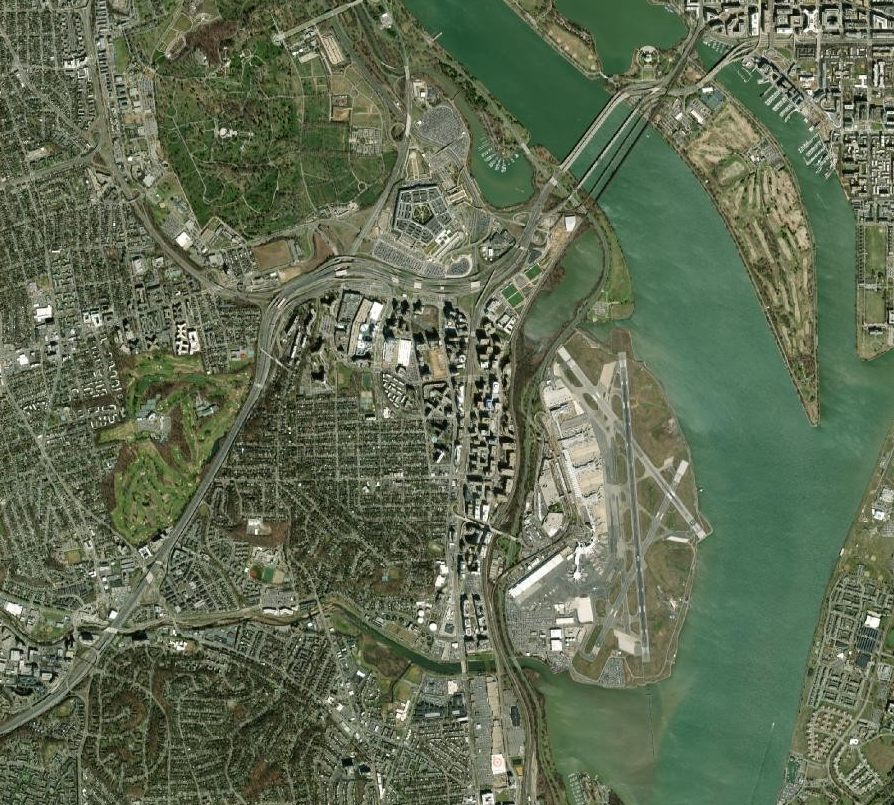

Potomac River shoreline downstream of Long Bridge in 1928, prior to construction of National Airport

Source: Library of Congress, Photographic mosaic map, Washington, D.C. (US Army Air Corps, 1928)

Potomac River shoreline downstream of Long Bridge in 2020

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The last major change in Columbia Island was the creation of the current shape of the Potomac Lagoon during the construction of the Pentagon starting in 1941. The river bottom was dredged for construction material, and Alexander Island was completely transformed by construction of the Boundary Channel and Pentagon Lagoon.

Alexander Island was located east of the modern Pentagon

Source: Library of Congress, Arlington County, eighteenth century

Dredge spoils from the Potomac River were placed on the Virginia shoreline, raising the elevation eight feet before construction of the five-sided structure built to provide a common headquarters for the Department of War and the Department of Navy. The land between the building and Boundary Channel was elevated, so no levee was needed on the Virginia shoreline for flood protection.

the Virginia shoreline at Alexander Island, prior to dredging the Little River/Boundary Channel

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of the District of Columbia (by Albert Boschke, 1861)

the boundary between Virginia-DC is the shoreline - except in places where the shoreline has been altered by adding dirt on the DC side of the 1791 boundary

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the postal address of the Pentagon (Washington, DC 20301-1400) does not reflect the boundary; the five-sided headquarters of the Department of Defense is located west of Boundary Channel - in Virginia

Source: District of Columbia GIS Services, DC Boundary

upstream from 14th Street Bridge in 1930, before completion of Columbia Island and construction of the Mount Vernon Memorial Highway

Source: Library of Congress, Aerial View Of Potomac And Area To Be Filled With Dredging Operation In Lower Right Corner, 1930

modern boundary of Arlington County, overlaid on 1865 map, shows how construction of Reagan National Airport (red X) altered the shoreline and expanded the land area of Virginia into the Potomac River

Source: Alexandria County GIS, AC Maps

Alexandria (now Arlington) County shoreline in 1900, showing Alexander Island

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Alexandria County, Virginia for the Virginia Title Cos

gray outline of runways at Reagan National Airport and modern Metrorail Blue Line route show changes in shoreline since 1900

Source: Alexandria County GIS, AC Maps

On October 31, 1945, Congress legislated a conclusion of the location of the 1791 high-water line. That action was needed in part to clarify that status of National Airport, which replaced Hoover Field.

National Airport had been built at Gravelly Point. When that site was a mudflat, it was clearly below the high water mark and within the District of Columbia.

After National Airport was built on dredged materials deposited on top of the mudflat, a portion of the Potomac River channel was converted into dry land. A location that had been below the low-water mark became dry land above the high-water mark. It was not obvious if the new, dry, above the high-water mark land became part of Virginia or was still within the District of Columbia.

in 1923, much of the future site of National Airport (south of Gravelly Point) was underwater - and therefore located in the District of Columbia

Source: Library of Congress, Port facilities at Washington D.C. & Alexandria, Va (Corps of Engineers, 1923)

Congress settled the question by passing a law that declare Virginia's boundary with the District of Columbia was the high-water line as of 1945. The law stated the boundary would change as water levels changed, but only after that date.

The legislation was intended to resolve the "no man's land" status where jurisdiction was unclear. A car crash in 1930, just south of the highway bridge between the southern bank of the Potomac River and the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks, revealed the problem. The Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, DC declined to respond to the incident, saying it had no authority for that 1,000 yards of highway. Police in both Alexandria and Arlington County also said the location was not within their jurisdiction. The US Park Police finally provided assistance in getting cars towed, but said they would not have authority for official action until the road segment was included in the planned George Washington Memorial Parkway.

In 1939, the District Attorney in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Attorney in Arlington County reached an arrangement for trying cases for incidents between the southern end of the highway bridge to the railroad tracks. Arlington County ended up with responsibility for handling legal matters in that territory, but both attorneys acknowledged that their agreement did not resolve the question of the boundary.

While advocating for the 1945 legislation, Rep. Howard W. Smith of Virginia told the US House of Representatives that prosecuting someone for a murder at National Airport would be difficult because jurisdiction was still unclear. After an employee died at the airport, 36 hours passed before permission to bury the body was finally granted. Supposedly the airport manager then distributed a memo directing employees to die elsewhere.

It took a year after the 1945 law was passed for some jurisdictional questions to get settled. One issue involved regulation of taxis.

The Civil Aeronautics Authority, which managed National Airport, signed a contract with a private company that defined rates for taxi and limousine trips to and from National Airport. The contract prohibited DC-based cabs which delivered passengers to the airport from picking up anyone for a return trip. After a year of debate and confusion, the District of Columbia Public Utilities Commission withdrew its regulations that had set prices for trips from Washington, DC to the airport and acknowledged that it had no authority to regulate activities in Virginia.19

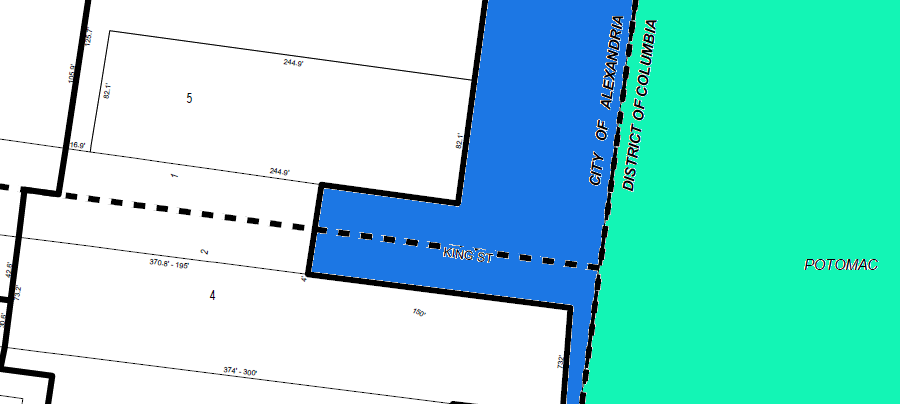

Congress made one significant exception to the shifting boundary provision: it exempted downtown Alexandria, from Second Street down to the boundary with Maryland at Jones Point.

from Second Street downstream to Jones Point, Alexandria's boundary juts out into the Potomac River

Source: Library of Congress, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Alexandria, Independent Cities, Virginia

The Corps of Engineers had defined a "pierhead" line on that stretch of riverfront in 1939, surveying the edge of waterfront improvements and how far the piers and docks extended into the river. The 1945 law bumped the Virginia boundary out from the high-water mark to the pierhead line, starting at Second Street. That created straight lines which put all of the developed waterfront within the jurisdiction of Virginia.

piers were built from the shoreline into the Potomac River along the Alexandria waterfront

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

dredges excavated the bed of the Potomac River to create National Airport, and the George Washington Parkway was relocated to provide space on the shoreline

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Oblique aerial view looking south of dredge and fill activities in the Gravelly Point area of the Potomac River for construction of Washington National Airport (DCA); November 16, 1939

it took an act of Congress in 1945 to determine that what is now Reagan National Airport was located in Virginia, above the mean high water mark of the Potomac River

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Air Transport, Airports, USA; Virginia, Washington (Ronald Reagan) National Airport

at Second Street, the boundary between Virginia-DC shifts from the high-water line to the pierhead line along the Alexandria waterfront - but even the City of Alexandria maps are still confusing

Source: City of Alexandria, GIS Parcel Viewer

District of Columbia maps show that its boundary shifts from the high-water mark to the pierhead line, near the Canal Center complex in Alexandria

Source: District of Columbia GIS Services, DC Boundary

Boundary disputes continued long after the 1947 survey of the high-water mark by the US Coast and Geodetic Survey.

The US Government filed suit in 1973 (United States v. Robertson Terminal Warehouse, Inc.) to resolve property rights on the "filled land" beyond the Alexandria shoreline that existed in 1791.

the shoreline in 1845 is today covered by "The Strand" along the modern Alexandria waterfront

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the town of Alexandria, D.C. with the environs (1845)

The Federal government did not seek to gain title to the land beyond the 1791 boundary out to the pierhead line, or to remove the modern structures. The lawsuit was designed to force waterfront landowners to allow public access along the river's edge, and to limit new development on the edge of Potomac River in Alexandria.

Most landowners settled rather than fight. The owners of the warehouses negotiated deals that authorized greater development density on their land, and Alexandria proceeded to build Oronoco Bay Park and Founders Park.

One of the 34 initial defendants was the Old Dominion Boat Club, which had a boathouse and marina at the foot of King Street. It had the resources and the will to contest the Federal claim and to litigate the case to closure. The boat club spent 38 years in court.

When the Federal government set up municipal government in the District of Columbia, it declared that state laws would stay in force. To decide a case initiated in 1973, Federal courts used Maryland law as it stood in 1801.

Virginia law was irrelevant to the case, since Maryland's state law applied up to the high-water mark of the Potomac River. In 1801, the state's common law allowed riparian landowners to build wharves and piers. There were no laws to protect the Potomac River's wetlands or other environmental resources in 1801; altering the shoreline for improved commerce, including creating new land, was permitted.

The US District Court rejected any claim that the riparian owners had gained title to the land through accretion, because the expansion of the shoreline had been by purposeful human action to create fill and wharves rather than by natural processes. The boat club won its case in District Court in 2008, and then won the appeal in Circuit Court in 2011, on different grounds.

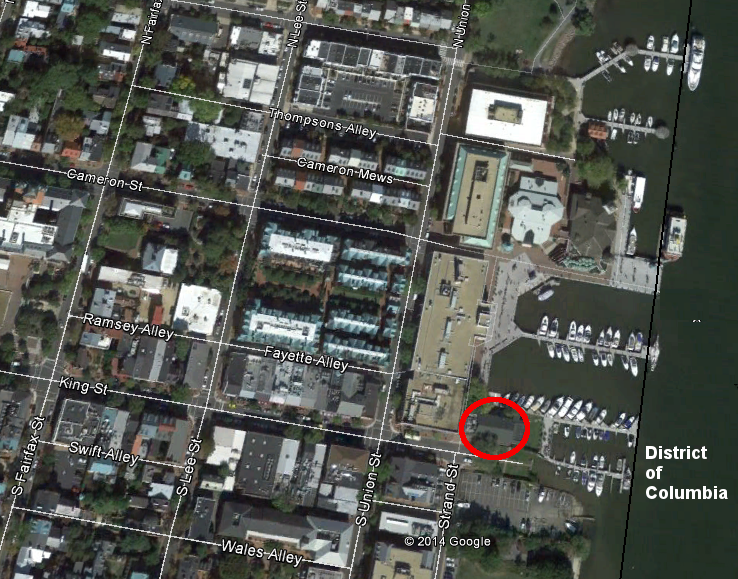

once passengers board the sightseeing boats that dock at Alexandria, they will be in the jurisdiction of the District at all times - beyond the pierhead line (Old Dominion Boat Club circled in red)

Source: District of Columbia GIS Services, DC Boundary

The Circuit Court affirmed the earlier decision that the boat club owned the land where it was located, because it was authorized under Maryland law to extend the shoreline:20

After the decision, Alexandria pursued its efforts to obtain public access to the river through the Old Dominion Boat Club. The city threatened to condemn the private property, and the club finally agreed to sell it. The price to acquire the boat club's half-acre of land at the end of King Street was $5 million.

The club relocated to a city-owned building at the end of Prince Street just one block away. A comparable 1983 plan to purchase the club's land and move it to the foot of Montgomery Street had been blocked by the Federal government, when it was claiming jurisdiction over the filled land beyond the 1791 shoreline.21

at the foot of King Street, the boundary of the District of Columbia is at the pierhead line on the Alexandria waterfront

Source: City of Alexandria, Tax Map 75.01

Resolution of public access facilitated implementation of Alexandria's Waterfront Small Area Plan. That proposal was controversial because it increased density in the area, increasing traffic and pedestrian congestion.

Opponents were able to get the number of hotels reduced from three to two, reducing the total number of rooms from 450 to 300, but were unable to reduce the planned increase in density at the sites of the old warehouses. The final settlement of the Federal government's claim to the ownership of the land underneath those warehouses had resulted in a legal settlement that provided for greater development density.22

the Robinson Terminal North warehouse will be redeveloped from industrial to housing/retail/commercial uses, following resolution of ownership issues and adoption of the Alexandria Waterfront Plan

Source: Alexandria Waterfront DRAFT Small Area Plan (p.46)

the US Geological Survey considered Alexander Island to be part of Virginia, not the District of Columbia, in 1900

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Washington-MD quadrangle (1:62,500 scale) (1900)

When an airplane crashed into the Potomac River on January 13, 1982, the Virginia-District of Columbia boundary affected the rescue effort. An Air Florida plane taking off from National Airport in a snowstorm failed to deice its wings effectively, and was unable to sustain flight. The plane clipped the 14th Street Bridge before crashing into the ice-covered Potomac River, killing four people in cars on the northbound span.

Arlington County firefighters reached the scene on the northbound bridge first, despite the massive traffic jam. District of Columbia officials arrived 30 minutes after the crash, and directed the Arlington personnel to leave the bridge because it was within the District. Arlington personnel then set up a staging area on the George Washington Parkway and assisted in recovering bodies.23

Source: Alexandria Archeology, Alexandria's Changing Boundaries, 1749 2024

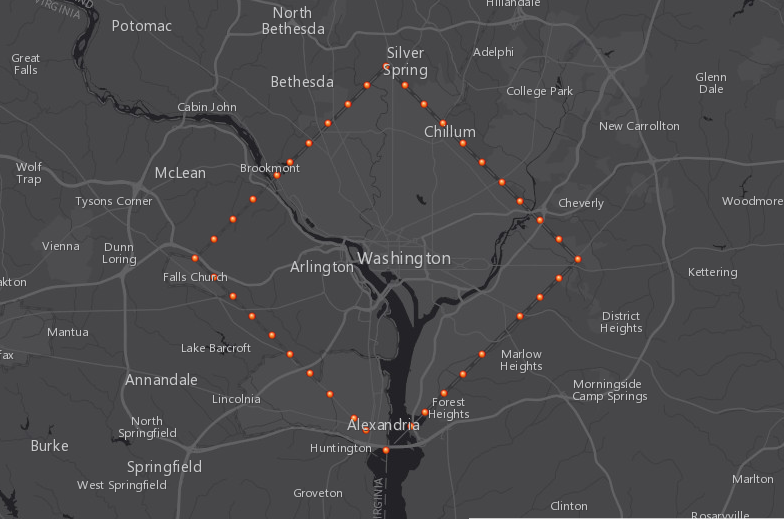

the boundary stones marking the District-Virginia and District-Maryland boundaries reveal the diamond pattern established by George Washington's decision to locate the southern tip at Jones Point

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online (with DC Boundary Stones layer)

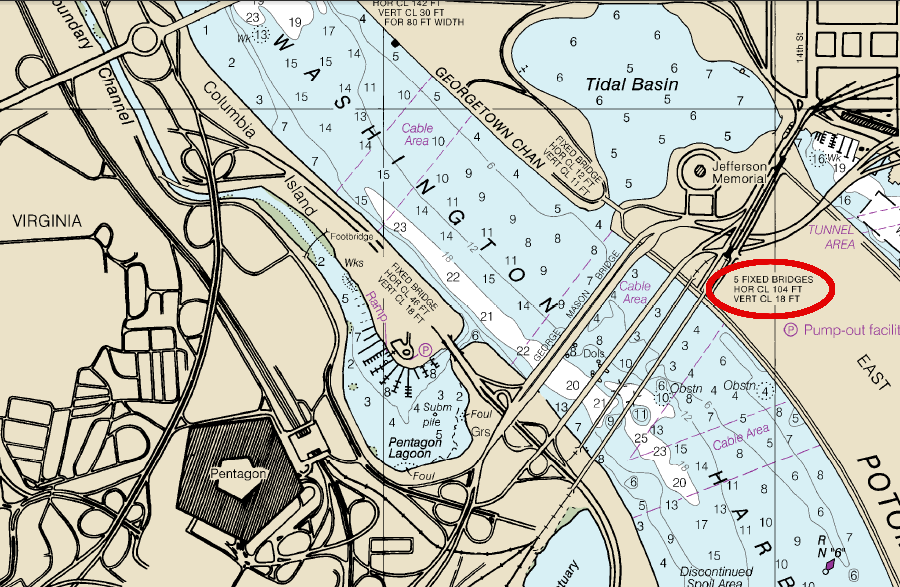

bridges downstream of the Pentagon have an 18' high limitation today

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Nautical Chart 12285 (Potomac River)

Boundary Channel at Pentagon, with red line showing border between DC and Arlington County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

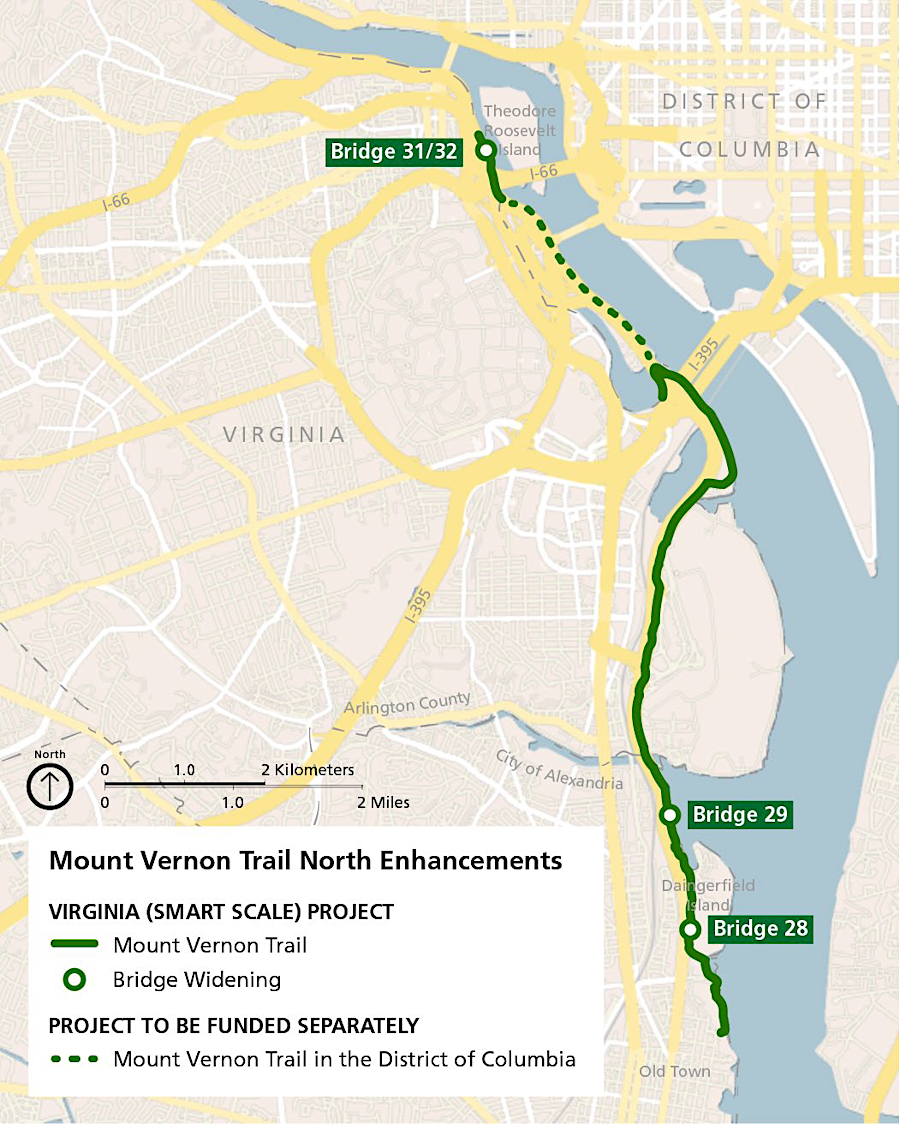

widening the Mount Vernon Trail required separate projects by Virginia and the District of Columbia

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Mount Vernon Trail North Enhancements

George Washington (on horse) chose the site of the new national capital, Pierre Charles L'Enfant (showing sketch to Washington) prepared the initial city plan, and many unnamed slaves and free black laborers (such as the unidentified man holding the horse) built the structures such as the US Capitol

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Capitol Site Selection, 1791