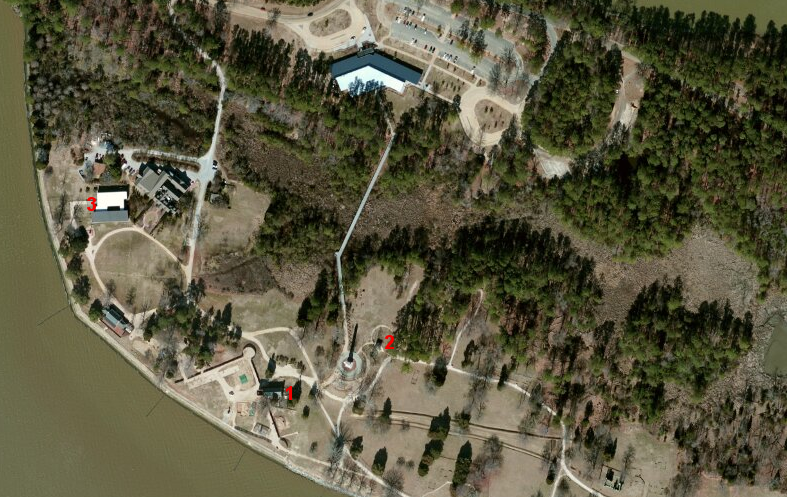

the first three statehouses at Jamestown were 1) the 1617 church, 2) Gov. John Harvey's home, and 3) the 1660 statehouse complex

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the first three statehouses at Jamestown were 1) the 1617 church, 2) Gov. John Harvey's home, and 3) the 1660 statehouse complex

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The first representative assembly in Virginia met between July 30-August 4, 1619 in the 1617 church building at Jamestown. That structure, the third church building in the colony, was owned by the London Company of Virginia. Separation of church and state in Virginia did not occur for almost another 170 years.

the General Assembly started meeting in 1619 in the church at Jamestown, which archeologists have located and partially reconstructed just west of the brick church that was built later in the 1600's

Starting in the 1630's, the General Assembly chose to meet in the home of Sir John Harvey. The colony purchased that private home in 1640, after Harvey was replaced as governor and had to sell his assets in Virginia to satisfy his debts.1

One year after Gov. William Berkeley arrived in 1642, he authorized the House of Burgesses to meet separately from the governor's Council. The Council probably met in Berkeley's three rowhouses at Jamestown once they were completed in 1646, and the House of Burgesses may have used that location as well.2

In 1660, the colony built a Statehouse specifically to support government operations on the western edge of the peninsula/island. The Statehouse complex of buildings was constructed over numerous graves that dated back perhaps as far as the 1609-10 Starving Time. The Statehouse was burned during Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, but Nathaniel Bacon had many of the official records removed first.

the footings of the "Archaearium," built at the site of the 1660 statehouse to house museum exhibits, were placed between the graves of the settlers buried there during Jamestown's first decade

the outline of the 1660 statehouse complex, beyond the Archaearium, is interpreted for modern Jamestown visitors

The post-Bacon's Rebellion replacement structure burned by accident in 1698.

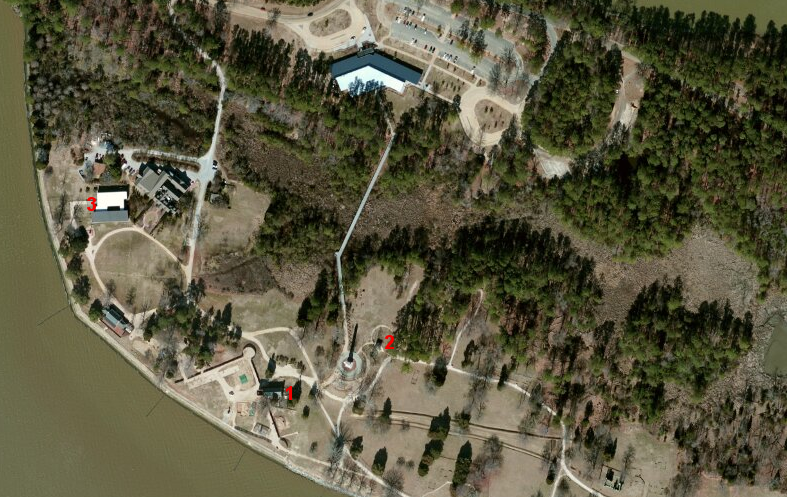

the statehouses in Jamestown were constructed from locally-made bricks

Source: National Park Service, Second Statehouse and Outbuildings (painting by Sidney E. King)

After that statehouse was destroyed, advocates for moving the capital finally defeated supporters of remaining in Jamestown. The General Assembly decided to build a new capitol in Middle Plantation, which was renamed Williamsburg after King William in London.3

The first capitol at Williamsburg took four years to build, but was complete in 1705. The first floor was designed as two large rooms separated by a plaza. The House of Burgesses met in a large room on the east side, while the General Court met on the west side. The Governor's Council, a separate unit of the colonial government since 1643, met on the second floor.

Governor Francis Nicholson chose to call the new structure occupied by the General Assembly a capitol rather than perpetuate the term statehouse. The new home built in Williamsburg for the governor's residence, finished after Governor Spotswood arrived in 1710, was called the "Governor's Palace." That term may have reflected the cost-overruns; the structure's original cost was projected to be £3,000 but final cost was £6,000.4

For 20 years the new capitol building was unheated; wood-burning fireplaces were added finally in 1723. Fire destroyed the building in 1747, though most of the brick walls survived. Governor Gooch encouraged rebuilding in Williamsburg, but the House of Burgesses approved rebuilding there in 1748 only by a close 50-48 vote. That decision blocked efforts to move the colonial capital (and build a new capitol) at a site accessible by water, potentially further inland on the Pamunkey River in Hanover County.

A new design was used for the second capitol building at Williamsburg, which was completed between 1751-53 on the same site. During the American Revolution, the legislators decided to move the capital further inland to Richmond.

The abandoned second capitol building in Williamsburg was used after 1780 for a variety of purposes afterwards. The building disappeared in stages. Half was demolished to recycle the bricks in 1793, and the remainder burned in 1832. Other structures were built on top of the old foundations, and even the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad tracks were run through the site in 1881.5

Visitors to Williamsburg today will see a reconstruction of the first capitol building, the one that burned in 1747. The decision by Colonial Williamsburg to rebuild the first capitol has created a historical anachronism for the colonial-era interpretation.

the Capitol building visited by tourists at Colonial Williamsburg is a reconstruction of the first Capitol building that burned in 1747, quite different from the second Capitol used in 1753-1779

Source: Wikipedia, Fifth Virginia Convention

Most reconstructions in the town represent the appearance of structures in the 1770's. Tourists going through the Capitol in Williamsburg are told it is significant because the colonial General Court and House of Burgesses met there. Visitors may learn they are on the site where the Fifth Virginia Convention declared the colony's independence from Great Britain on May 15, 1776.

However, few know that the reconstructed building used for tours does not reflect the 1776 structure. The building is modeled after a Capitol that disappeared almost 30 years before the American Revolution.

the second Capitol was completed in 1753, and abandoned in 1779 when the capital moved to Richmond

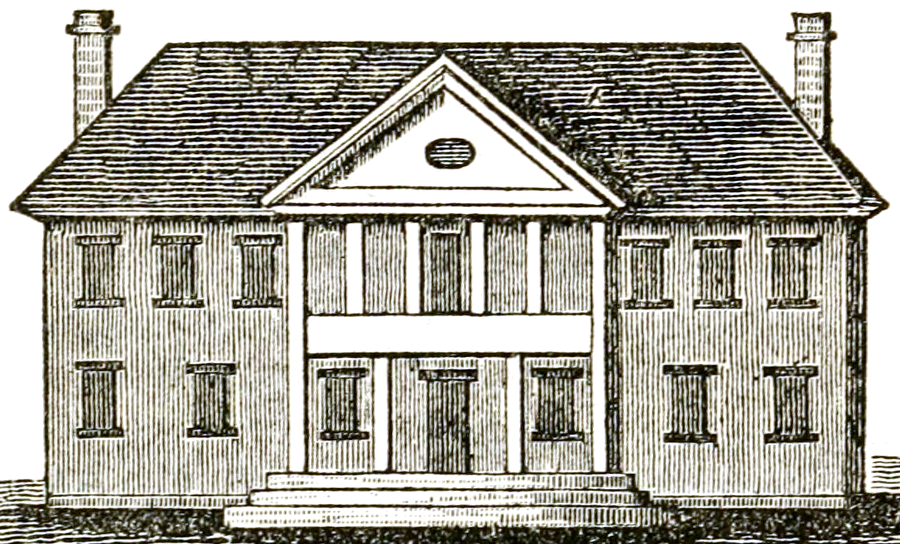

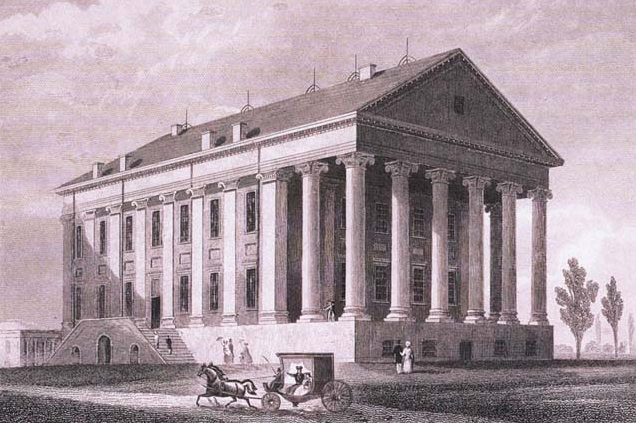

Source: New York Public Library, The old Virginia capitol

Since John D. Rockefeller started providing the funding, Colonial Williamsburg has focused on recreating how the town looked at the time of the American Revolution. Reconstruction of the building that burned in 1747 rather than the structure that existed in the 1770's has created the "schizophrenic problem of narrowly focusing on the events of the Revolution in the wrong building" because the:6

the second Capitol building, where Virginia declared independence in 1776, does not resemble the reconstructed version of the first Capitol now on display at Colonial Williamsburg

Source: Historical collections of Virginia, Skirmish at Richmond, Jan. 5th, 1781 (p.329)

Scholarship completed after the reconstruction in 1934 has revealed errors in the replication of even the first capitol. The rebuilt version is more grand and more symmetrical than what the colonists built in Virginia at the start of the 18th Century.

Just as Jamestown was replaced by Williamsburg, Williamsburg was replaced Richmond as the capital city. Jefferson proposed the move in 1776, but the General Assembly did not decide to abandon Williamsburg until later in the American Revolution, in 1779.

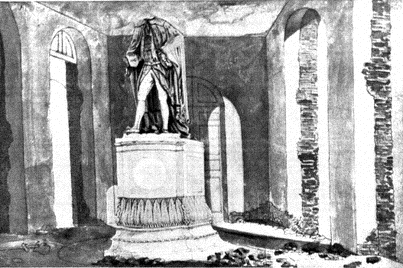

the statue honoring Lord Botetourt was vandalized after the Capitol building in Williamsburg was abandoned in 1779

Source: Library of Congress, The journal of Latrobe; being the notes and sketches of an architect, naturalist and traveler in the United States from 1796 to 1820

Moving the capital further inland was expected to reduce the potential of enemy attack, mimicking the old advice of the London Company in 1606 to locate Jamestown far upstream to avoid the Spanish.

Moving inland was good advice in 1606, but Richmond was not far enough inland in 1781. The British found they could seize that new capital without much effort during the American Revolution. In 1781 Benjamin Arnold and then Gen. William Phillips forced the rebellious Virginia leaders to flee. At one point, the General Assembly met as far inland as Staunton.

When Benjamin Arnold led British troops and organized loyalists to Richmond in January, 1781, American defenses collapsed quickly. After forcing the militia to flee and reaching Church Hill, Arnold sent Governor Thomas Jefferson a proposal - allow his troops to remove the valuable tobacco from the private warehouses, and Arnold would not burn the capital. Jefferson rejected the proposal, and from his safe location in Manchester he was forced to watch Arnold destroy public records and burn tobacco-filled warehouses.7

Because the capital of Virginia had been moved from Williamsburg only in 1780, there was no capitol building when Richmond was captured by Benedict Arnold. The legislators were meeting in two commercial buildings at the corner of 14th and Cary Streets when the British arrived in January, 1781. Government officials fled before the British soldiers reached Richmond. When Arnold destroyed other parts of the capital city, he ignored the wooden structures that had been rented for the "rebel" legislators.

The General Assembly met in the same rented commercial buildings for seven years after they returned to Richmond in October, 1781. The legislators finally moved from the corner of 14th and Cary Streets after the new Jefferson-design capitol building on Shockoe Hill was ready for occupancy in October, 1788. By 1811, those commercial buildings had been torn down.8

The location of that new building on Shockoe Hill was determined in May, 1780, when the General Assembly passed "An act for locating the publick squares, to enlarge the town of Richmond, and for other purposes." That law also called for separate buildings to house officials responsible for legislative, executive, and judicial functions, reflecting the separation of powers defined in the 1776 Virginia constitution.

St. Johns Church, where Patrick Henry made his "give me liberty or give me death" speech during the Second Virginia Convention in 1776, was a more-central location that Shockoe Hill. The government chose to move from the Governor's Palace and Capitol in the center of Williamsburg to a site that was on the western edge of Richmond. In the new capital, Shockoe Hill offered six squares of undeveloped land, enough for the state to create Capitol Square and erect different government buildings.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe painted the Virginia State Capitol on what was renamed Capitol Hill

Source: Bruce Guthrie Photos, VA -- Richmond -- State Capitol -- Interior Images

Soon after moving the state government to Richmond in April, 1780, Governor Thomas Jefferson - who was also Director of the Public Buildings of Virginia - started planning the extension of city streets and the development of public buildings on Capitol Hill (formerly Shockoe Hill).9

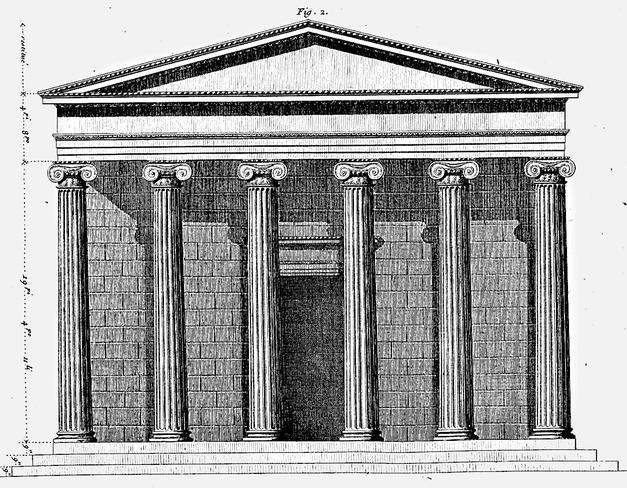

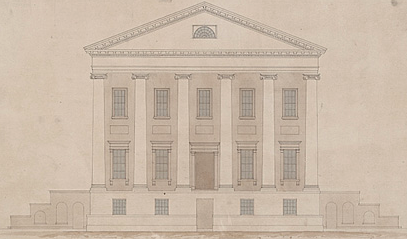

when designing the Virginia State Capitol in 1785, Thomas Jefferson drew inspirations from engravings of the Temple of Erectheus in Athens

Source: David Le Roy, Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grece (Seconde Partie, opposite p.14)

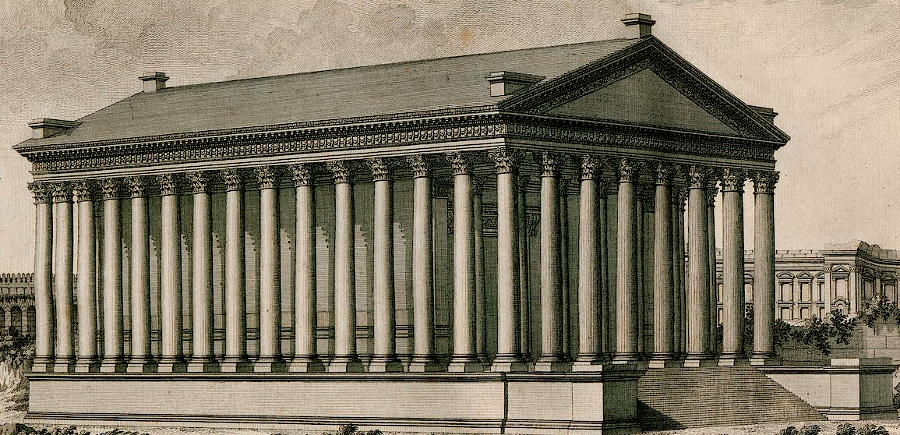

the ruins of the Temple of Bacchus at Baalbek (modern Lebanon) provided a classic, cubic model for Jefferson

Source: Robert Wood (editor), The ruins of Balbec, otherwise Heliopolis in Coelosyria (Plate XLI)

In partnership with French draftsman Charles-Louis Clerisseau, Jefferson designed a new capitol building using ideas from engravings that he saw of several classic temples. Sources of inspiration included the temple of Erectheus at Athens, a temple at Balbec, and the Maison Carree in Nimes. Thomas Jefferson wrote James Monroe:10

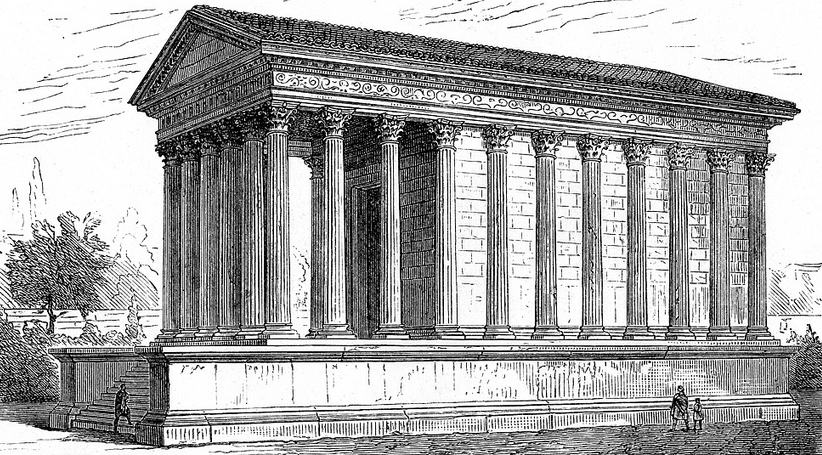

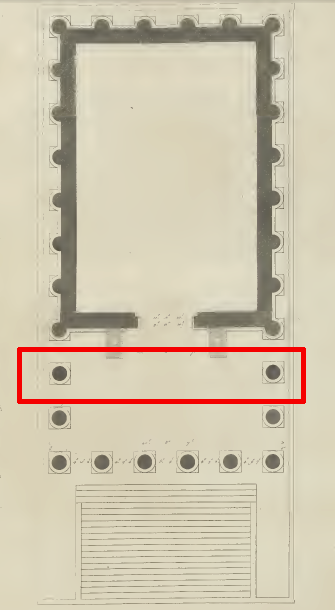

Charles-Louis Clerisseau and Thomas Jefferson used the well-preserved Maison Carree in Nimes as their model for the third and final design of the Virginia State Capitol

Source: Penn State University Libraries, Maison Carree: rendering of exterior view

Thomas Jefferson relied upon the drawings by Charles-Louis Clerisseau of the Maison Carree in Nimes, and did not have time to visit the building in person

Source: Archives savantes des Lumieres - Correspondance, collections et papiers de travail d'un savant nimois: Jean-Francois Seguier (1703-1784), En ligne: lettres de Charles-Louis Clerisseau

Jefferson made one modification of the design, eliminating one of the three rows of columns in the portico. Clerisseau suggested that more light would illuminate the interior of the portico was made wit two rather than three columns, and cost would also be reduced.

Jefferson suggested the Directors of the Public Buildings of Virginia, the men in Richmond with the responsibility of constructing the building, might consider altering his alteration. Restoring the third column would restore the original proportions of the Roman temple, and Jefferson noted:11

Thomas Jefferson reduced the portico, eliminating one of the three columns used at Maison Carree

Source: Archives savantes des Lumieres - Correspondance, collections et papiers de travail d'un savant nimois: Jean-Francois Seguier (1703-1784), En ligne: lettres de Charles-Louis Clerisseau

Jefferson's concept of basing public buildings on the design of temples can be dated further back to 1771-72, near the start of Lord Dunmore's service as colonial governor. When he was around 30 years old, Jefferson sketched out plans for what may have been a replacement for the Governor's Palace. He drew ideas from Palladio's Four Books on Architecture, but Jefferson initiated the idea of using neoclassical design for public buildings.12

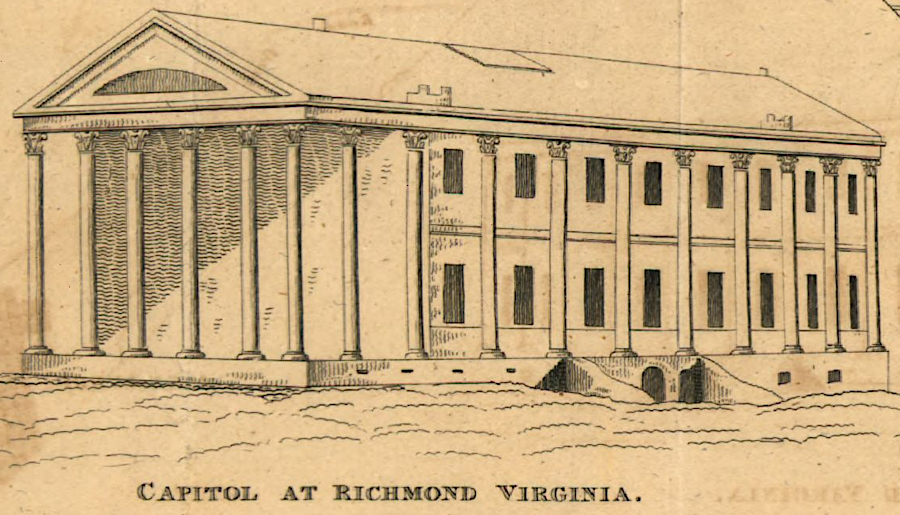

Thomas Jefferson initiated the neoclassical style of architecture for public buildings in the United States, when he designed the Capitol of Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson: Creating A Virginia Republic

The workers who built the new capitol were a mixture of enslaved people, free blacks, and whites. They started construction in 1785, and the building was first use by the legislature in 1788.

In 1785, Jefferson had recently completed Notes on the State of Virginia. He stated in that book that ending slavery would create a social problem if blacks and whites continued to live in the same area;m that might lead to miscegenation. Jefferson assumed different races could live together and work together on a building in Richmond, but if slavery were ended then blacks would have "to be removed beyond the reach of mixture."

The exterior of the new capitol, built according to Jefferson's design with one major exception, was completed in 1798. The exposed brick was whitewashed to provide a more impressive appearance. Jefferson had proposed grand steps on the southern side of the building, but they were not added until wings were added in 1902-04.13

the steps on the South portico of the Capitol were not built, as Jefferson designed, in 1798

Library of Virginia, Jefferson and the Capitol of Virginia

The exterior may have been painted in different colors, even after the exterior was covered with stucco with lines inscribed to make it look like stone. Mimicking stone created a false but grander look for the state legislature's building, similar to the approach used by George Washington for the exterior of Mount Vernon and by Thomas Jefferson at the entrance to Monticello.

Jefferson's model of the capitol, sent from France to guide construction of the building in the 1780's, has five different paint schemes that apparently reflect the different exterior appearances between 1798-1904.14

the paint scheme for the Virginia State Capitol, prior to the coating with stucco, is not well understood but may have included contrasting colors

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia State Capitol (Howard W. Montague, attributed)

In 1860, the Virginia Association for Erecting a Statue to Henry Clay raised funds and erected a statue of Whig leader on Capitol Square, with a gazebo surrounding him. The statue joined Houdon's marble depiction of Washington inside the Capitol, which had been erected in 1796, and the 60' high bronze Washington monument outdoors (surrounded by historical and allegorical figures) that had been dedicated on February 22, 1858. The gazebo was removed and the Henry Clay statue was moved inside the Capitol in the 1930's.

the Henry Clay statue, surrounded by a gazebo, lasted for over 70 years in Capitol Square

Source: New York Public Library, Statue of Henry Clay, Richmond, Va

During the Civil War, Richmond became the capital of the Confederacy. Between July 1861-March 1865, the Virginia State Capitol served double-duty as the meeting space for the Confederate Congress as well as the Virginia General Assembly, minus the members from western counties who created the Restored Government of Virginia and met in Wheeling until West Virginia was created in 1863.

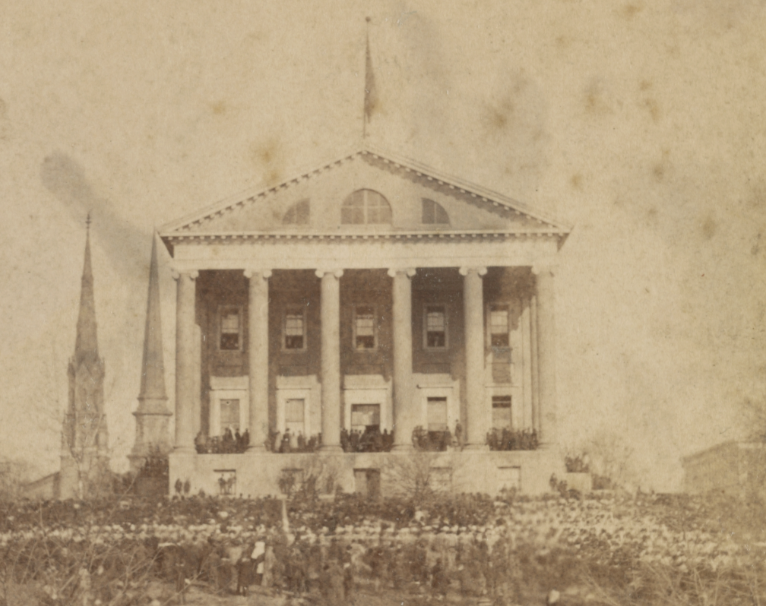

Virginia State Capitol during the Civil War

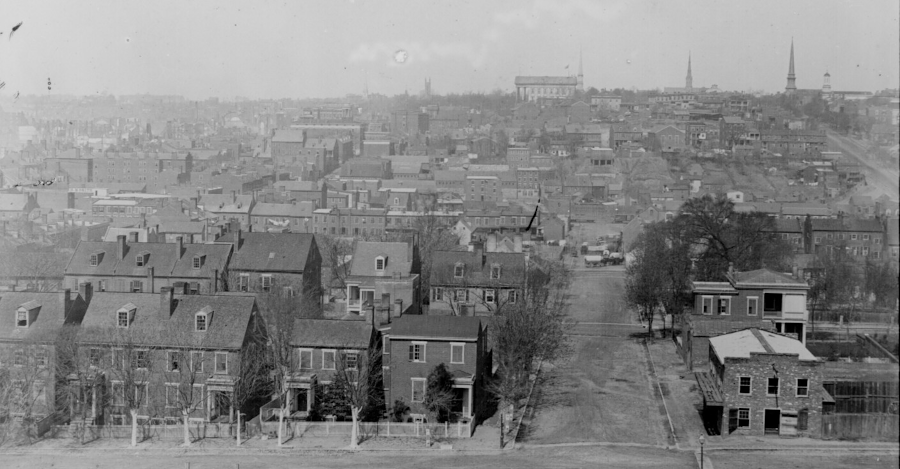

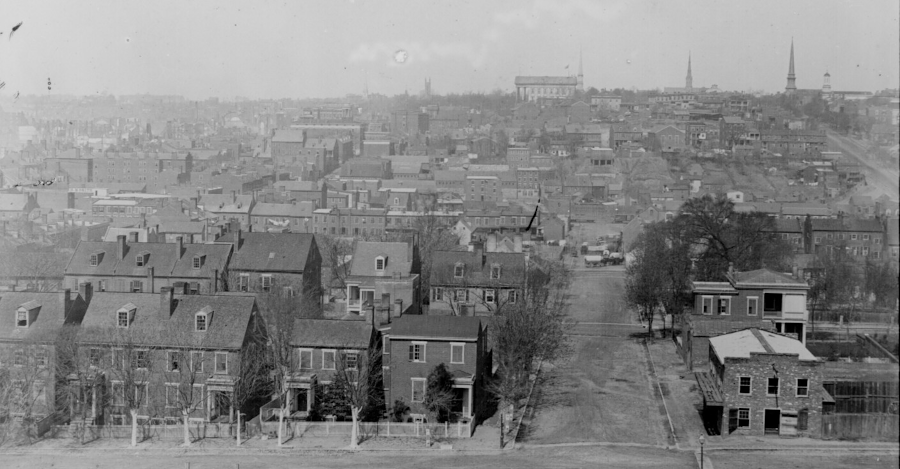

Source: National Archives, View of Richmond, Va

Starting on July 20, 1861, the Third Session of the Provisional Congress of the Confederacy met in the Virginia State Capitol. The Virginia General Assembly had adjourned in April, and the Virginia Convention of 1861 concluded at the end of June after voting to invite the Confederacy to move its capital from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond.

Virginia State Capitol during the Civil War

Source: National Archives, Map of City of Richmond, Virginia (c.1858); High-angle view toward the capitol

Until the first Confederate elections in November 1861, it was a unicameral body. Meetings of the Confederate Congress between July 20-September 3 were held in the one room used by the Virginia House of Delegates, on the north side.

After members of the Confederate Senate were chosen, the Virginia Senate's chamber on the opposite side of the Capitol was reconfigured to serve as the Confederate Congress's House of Delegates meeting space. That allowed the Virginia House of Delegates to reclaim its room, while the Senate of Virginia moved to a new location one floor higher in the building. The Confederate Senate also met on that upper floor during its existence between 1862-1865.

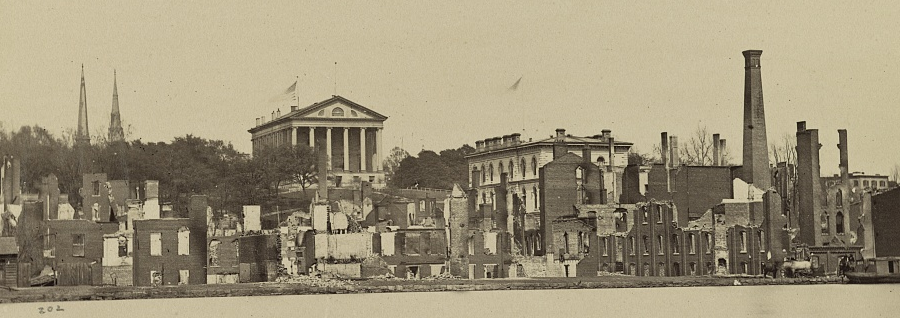

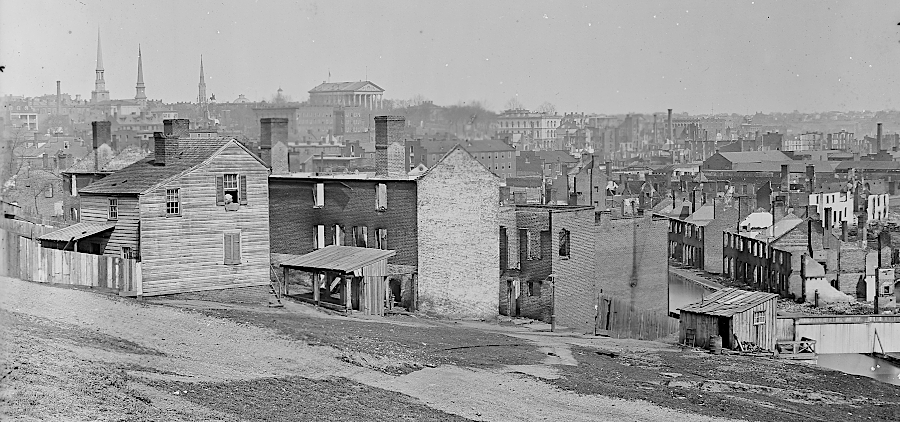

the State Capitol building and church steeples dominated the Richmond skyline in the 1800's

Source: Library of Congress, View of Richmond, Virginia (c.1865)

At one point in December 1861, the building hosted four separate elected groups - the Virginia General Assembly, the Confederate Congress, the reconvened Virginia Convention of 1861, and the Electoral College counting votes for President and Vice-President of the Confederacy. The General Assembly found the building to be crowded, but rejected a proposal in 1863 to purchase the nearby Exchange Hotel and convert it into a new capitol for the Confederate Congress.

The Confederate Congress's last meeting was in the State Capitol on March 18, 1865.15

the Capitol was used by both the Virginia legislature and Confederate Congress for four years

Source: Illustrated London News, The Civil War in America: Sketches from Richmond, Virginia (August 10, 1861)

a crowd assembled at the Capitol after the Confederate victory at Manassas in July, 1861

Source: Library of Congress, State Capitol

The Evacuation Fire in April, 1865 destroyed many official records stored in buildings at the base of Capitol Hill, but the flames did not reach the capitol building itself.

A steam heating system was installed in the Capitol after the Civil War. The coal-burning stove barged up the James River from the Williamsburg House of Burgesses in 1780, and ordered a decade earlier by Governor Botetourt, was finally retired. That stove had originally been used to warm the House of Delegates room in Richmond and was then moved to the Rotunda. Since 1933, the stove has been on loan to Colonial Williamsburg.

Capitol Square (looking northwest from the corner at 9th and Bank Street) provided a buffer of green space that protected the capitol building from destruction in the 1865 Evacuation Fire

Source: Library of Congress, View of capitol square

the Virginia State Capitol survived the April, 1865 Evacuation Fire without damage

Source: Illustrated London News, View taken from south side of Canal Basin, Richmond, Va., showing Capitol, Customs House, etc., April, 1865

Virginia State Capitol after the Evacuation Fire in April, 1865

Source: National Archives, Ruins of Richmond, Va

the Capitol in Richmond after arrival of the Union Army (note that the main entrance was on the side, not via the colonnade in the front)

Source: Library of Congress, The State Capitol, Richmond, Va., April, 1865

steps were not added on the front (south side) of the Capitol building until 1904-1906, when the wings were added on the east and west sides to create chambers for the House of Delegates and State Senate

Source: Library of Congress, Richmond, Va. Front view of Capitol (1865)

Thomas Jefferson has anticipated separate structures on Capitol Square for legislative, executive, and judicial operations of the state government. A separate Executive Mansion was completed in 1824, but budget constraints limited construction of courthouses. A courtroom was built above the House of Delegates chamber, with a gallery above that courtroom for observers. The support pillars affected the view inside that chamber, and those pillars were removed. The courtroom sagged but remained intact until 1870.

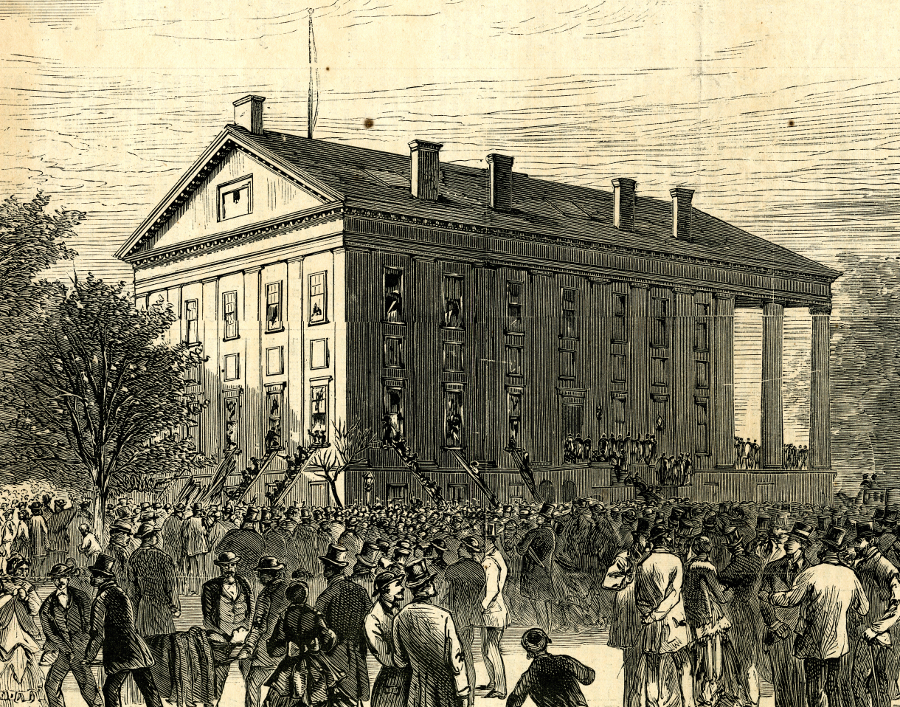

In 1870, a legal fight over the selection of the mayor of Richmond after the end of Reconstruction attracted a large crowd. Up to 400 people crowded into the Supreme Court of Appeals in that courtroom above the House of Delegates. The center beam supporting the courtroom finally broke, the gallery collapsed, and everything fell down into the unoccupied House of Delegates chamber:16

the collapse of the courtroom and gallery filled with observers of a court case in 1870 resulted in the Capitol Disaster, killing 62 and wounding about 200 people

Source: Harper's Weekly, Richmond calamity -- Interior of Hall of Delegates -- Getting out the dead and wounded (May 14, 1870) digitized by Virginia Commonwealth University, James Branch Cabell Library - Special Collections and Archives

rescuers had to use ladders to get into the House of Delegates chamber, since the Virginia State Capitol was built above a full basement

Source: Harper's Weekly, Richmond calamity -- Removing the dead and wounded from the Capitol (May 14, 1870) digitized by Virginia Commonwealth University, James Branch Cabell Library - Special Collections and Archives

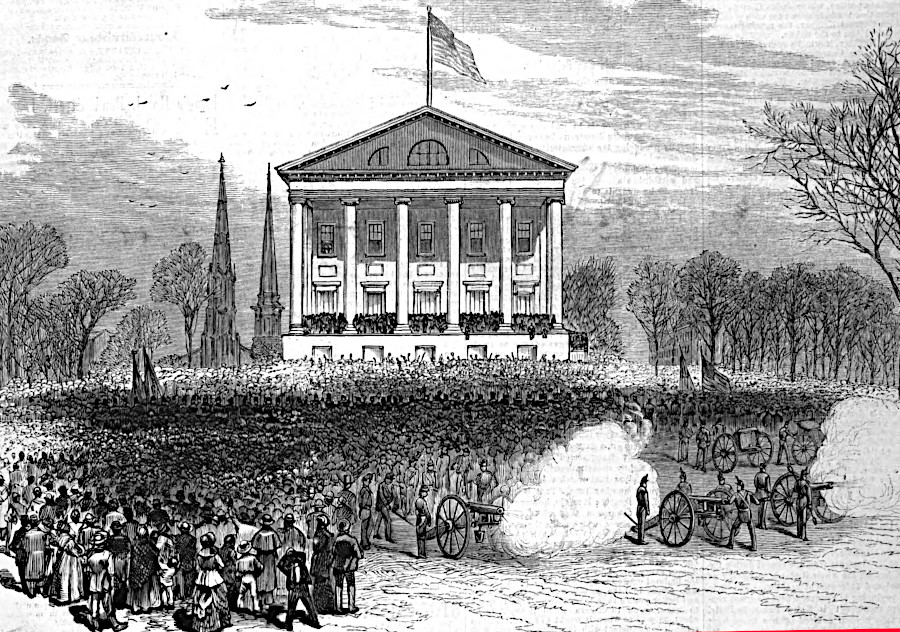

the Capitol in 1878 during the inauguration of Governor Frederick Holliday

Source: Hathi Trust, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (January 19, 1878, p.315)

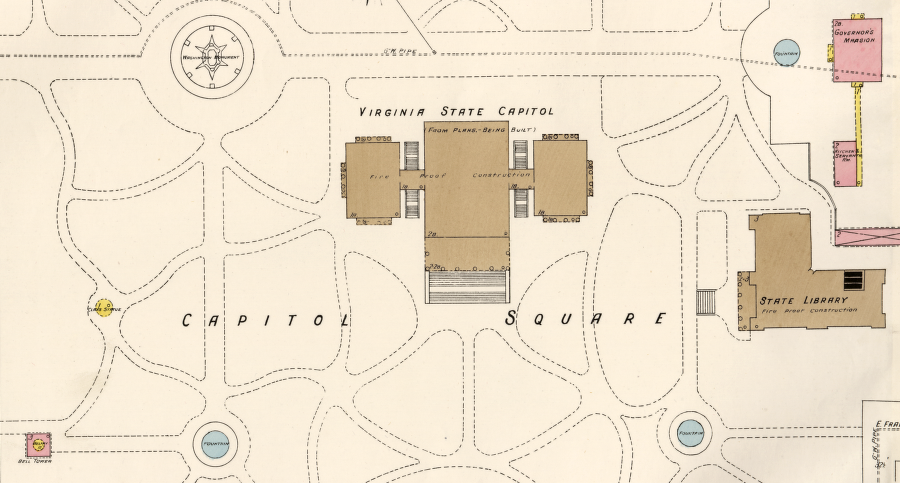

The Capitol was expanded in 1904-1906. New wings were constructed to provide chambers for the House of Delegates (on the east side) and State Senate (on the west side).

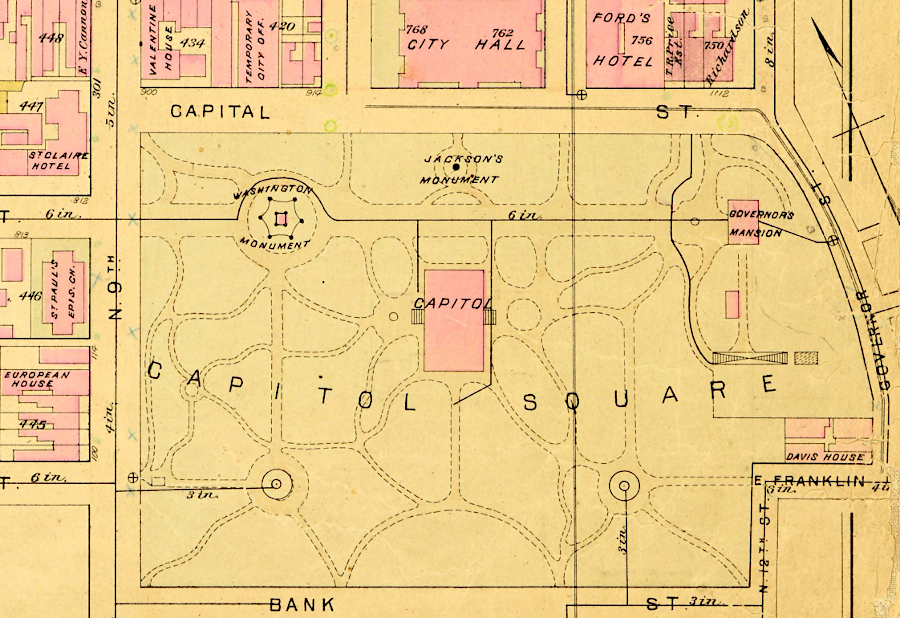

the State Capitol had no wings until the 1904-1906 expansion

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University, Baist Atlas of Richmond - Outline & index map Richmond and vicinity (1899)

Steps were finally constructed on the South Portico of the building. The old steps on the sides of the building were removed as the wings were added. The original pine tree center posts are still inside the Ionic columns on the South Portico.17

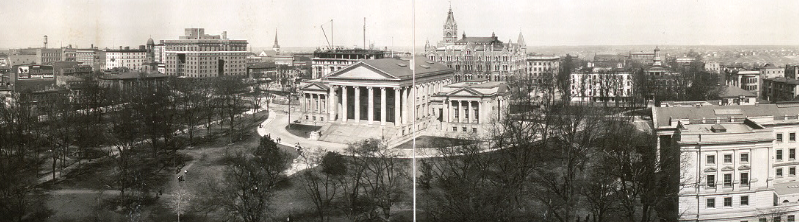

in 1912, the State Capitol had expanded so the House of Delegates could meet in an eastern wing (on the right - view is looking north) and the State Senate in a wing on the western side

Source: Library of Congress, Panoramic view of Richmond, Va

Capitol building on September 3, 1920 after wings were added

Source: National Archives, Virginia - Richmond

Capitol Square, 1954

Source: Library of Virginia, Adolph B. Rice Studio, State Capitol

In 1964, the hallways ("hyphens") connecting the original building to the wings were expanded. They were widened to create more work space for the state legislators.

the 1904-1906 expansion linked two new wings to the main structure with narrow hyphens

Source: Library of Congress, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Richmond, Independent Cities, Virginia (1905)

Between 2005-2007, a major reconstruction of the building ensured its stability. Water leaks had converted some of the original hand-fired brick back into clay. Before the state committed to the $100 million restoration project and forced the General Assembly to meet in the Patrick Henry Building for the 2006 and 2007 sessions, a maintenance worker commented to a reporter:18

The reconstruction left the exterior appearance mostly intact, though the old skylights in the rotunda and the original House and Senate chambers that had been covered in 1906 were reinstalled. Walls were repainted to match the colors used a century earlier. Queen Elizabeth II visited the Capitol to celebrate the completion of the project.

The project also added a new entrance on Bank Street and 27,000-square-foot underground expansion, including a visitor center. The construction disrupted the landscape, which was first formally designed in 1816. The park that was designed by Maximilian Godefroy was enclosed by an iron fence in 1818, creating the "square." In 1850, John Notman created the design of meandering walkways that is still a fundamental part of Capitol Square.

The 2007 expansion included a new skylight on top of the underground chamber. Continuing the architectural tradition, it soon began to leak. Building engineers suspected that pedestrians and Segways crossing the surface of the skylight at ground level might be facilitating the leaks, so in 2019 a metal fence was installed in Capitol Square to block off the skylight. The actual cause remained a mystery, and one member of the Capitol Square Preservation Committee noted:19

between 2004-2007, a 27,000 square-foot underground extension was constructed on the south side of the Capitol

Source: Draper Aden Associates, Virginia State Capitol

excavating new meeting space below the south lawn of the Virginia State Capitol

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia State Capitol, Bank and 10th Streets, Capitol Square, Richmond, Independent City, VA (Image #87)

security measures on Bank Street include barriers to vehicle traffic

Throughout the State Capitol, walls, ceilings, and niches are painted with leaves that resemble tobacco. The presumed linkage to Virginia's agricultural heritage has been highlighted by politicians, but with one possible exception no tobacco plants are painted on the walls.

The leaves and branches with berries represent laurel, while those without berries represent acanthus. Both plants are common symbols in Greek and Roman temples. The one possible place for sighting tobacco leaves in the Capitol is in the corners of the third-floor ceiling next to the rotunda. Indistinct long leaves there could be described as tobacco.20

Virginia State Capitol

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia State Capitol, Bank and 10th Streets, Capitol Square, Richmond, Independent City, VA (Image #14)

The interior of the Capitol has changed over time, just like the exterior.

In 1931, a life-sized statue of Robert E. Lee was installed on the floor of the Old House Chamber in the Capitol. The 900-pound bronze statue showed Lee dressed in military uniform, and was placed at the spot where he accepted command of the Virginia military forces in 1861. The House of Delegates had moved its regular meetings to a new chamber after the Capitol was expanded in 1904, and the Old House Chamber became a museum as well as location for ceremonial events.

Busts were also added in the Old House Chamber over time to honor Confederate Generals Fitzhugh Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, Stonewall Jackson, and Joseph E. Johnston. Three busts honored Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Vice-President Alexander Stephens, and "Pathfinder of the Seas" Matthew Fontaine Maury. In addition, the United Daughters of the Confederacy installed a plaque on the wall honoring Thomas Bocock. He was a lawyer from Appomattox who served as the Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Confederate States of America. That political body met in the House chamber between 1862-65.

George Floyd was murdered in May, 2020, triggering a Black Lives Matter reaction that included demands for removal of Confederate monuments from places of honor. The Speaker of the House of Delegates secretly arranged for the statue of Lee, the seven busts, and the plaque to be removed one night in July, 2020. Reporters were allowed to document the event, but they were sworn to secrecy until it was completed.

The artifacts were placed in storage, and the Speaker appointed a bi-partisan advisory group to determine how to handle them. The chair of the Speaker's Advisory Group on State Capitol Artifacts commented after the removal:21

The Republican leader in the House of Delegates objected to the removal, especially without notice to the minority party leadership and in the "dead of the night." When the Speaker claimed, incorrectly, that there were no records of the $83,000 contract for the removal, a judge in the Richmond General District Court fined her for violating the Virginia Freedom of Information Act.

In 2021, the Republican leader in the State Senate proposed legislation to require review by the Capitol Square Preservation Council of proposed changes to monuments, statuary, artwork, or other historical artifacts within the Capitol. The Rules Committee in the House of Delegates rejected the proposal, with several members objecting to an effort to diminish the authority of the first female Speaker of the House.22

Jean-Antoine Houdon's statue of George Washington in Virginia State Capitol

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia State Capitol, Bank and 10th Streets, Capitol Square, Richmond, Independent City, VA (Image #41)

Also in 2021, the General Assembly voted to remove the state of Harry F. Byrd Sr. from the Capitol grounds. The statue had been installed in 1976 using private funds. Harry F. Byrd Sr. was the leading Virginia Democrat for half of the Twentieth Century. He served as a State Senator from 1916-1926, as Governor between 1926-1930, and as a US Senator from 1933-1955.

In 2020, a conservative Republican in the House of Delegates was frustrated by proposals from the newly-elected Democratic majority to remove Confederate monuments. He tried to "call their bluff" by proposing to remove Byrd's statue.

To the delegate's surprise, the Democrats endorsed his proposal. Byrd had been a key architect of Massive Resistance in the 1950's, and led efforts to maintain white supremacy throughout his political career. A year later, the House of Delegates voted 63-34 and the State Senate voted 36-3 to remove Byrd's statue.23

The governor's traditional office is located on the third floor of the Capitol; it is now used primarily for ceremonial functions. When the Executive Branch began preparing a centralized budget, the Division of the Budget was placed on the third floor as well.

The budget office was located near the governor's office from 1922-1962, when the budget staff moved to remodeled attic space in the Capitol. During the 2005-2007 restoration of the Capitol, the working offices of the governor transferred to the Patrick Henry Building.24

Legislators continue to refer to the location of the governor's office in the Capitol when complaining about decisions made in the Executive Branch. In 2021, after the State Senate rejected a budget amendment proposed by Governor Ralph Northam that would have required small businesses to do extra paperwork so part-time workers could enroll in a state-run retirement savings plan, a state senator commented sourly:25

Today the governor's office and staff are located in the Patrick Henry Building on Broad Street. That building is just north of the Capitol, between the Executive Mansion and the General Assembly Building which is on the corner of Ninth and Broad streets.

Patrick Henry Building, as seen from the State Capitol

The General Assembly and the Governor approved a plan in 2016 to replace the office spaces of the legislators. The House of Delegates and the State Senate almost always held formal sessions in separate wings of the Capitol in Richmond, but since 1975 the 140 legislators and their committee staff had been located in a General Assembly Building (GAB). The office building was a combination of four old buildings at the southeast corner of Broad and Ninth streets. They included the 1912 Life Insurance Company of Virginia building, a 1923 Beaux Arts addition, and a 1965 modernist addition that replaced the 1911 Lyric Theater.

Legislators and staff prided themselves on their ability to navigating the maze of hallways and rooms. Citizens trying to meet with state officials often expressed frustration with the confusing interior design. Maintenance was deferred for decades. Mold accumulated in the walls, and there were enough holes in the ductwork for birds to get inside.

The "old" General Assembly Building was replaced with a new General Assembly Building between 2017-1023, as part of a comprehensive Capitol Square construction project managed by the Department of General Services. The project also included a 500-car parking garage at the corner of Ninth and Broad, with a $32 million tunnel connecting to the legislature's new office building.

offices of the 140 members of the General Assembly are now on the the corner of Ninth and Broad

The 2020 General Assembly approved an additional $25 million to construct a 600-foot tunnel between the Capitol and the new General Assembly Building. Like the tunnel connection to the parking garage, the tunnel increased security as well as increased convenience in traveling to the Capitol (particular on rainy and cold winter days). Visitors to different buildings in the Capitol complex would not be required to go through repeated screenings. If security risks were elevated due to a threat, access to the tunnel could be limited to just elected officials and their staff.

construction of the tunnel connecting the new General Assembly Building to the extension south of the Capitol cost over $20 million

Source: Department of General Services, DGS Capital Outlay Projects Update (January 20, 2023)

The new General Assembly Building was 14 stories tall, with an additional underground story as well. A facade of the 1912 Life Insurance Company of Virginia building was retained and now forms the southeast corner of the new building. The limestone wall with carved eagles, cherubs and winged horses was protected during construction by a steel exoskeleton.26

The replacement of the General Assembly Building was completed and the new building opened on October 11, 2023. The chair of the Senate Rules Committee said prior to the dedication ceremony:27

Source: EarthCam, Time-lapse Video of Richmond's new Virginia General Assembly Building by RAMSA

a steel skeleton during construction of the new General Assembly Building (GAB) protected a facade of the 1912 Life Insurance Company of Virginia building

Source: EarthCam, Time-lapse Video of Richmond's new Virginia General Assembly Building by RAMSA

During construction of the new General Assembly Building, the 140 legislators and their committees met in the Pocahontas Building across Bank Street from the Capitol. That structure had been built in two phases. The West Tower was completed in 1923 and housed the State Planters Bank. The East Tower was added in 1962. Both had a steel frame with limestone facades. The Pocahontas Building was listed as a contributing structure to the Main Street Banking Historic District.

The COVID-19 pandemic and supply chain disruptions delayed completion of the new General Assembly Building, so the Pocahontas Building remained in use during the 2023 General Assembly. The Capitol Square project originally envisioned replacing the East Tower and renovating the West Tower.28

the new General Assembly Building (red X) is on the opposite side of Capitol Square from the old Pocahontas Building (circled)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS online

Investing in new office buildings and allocating space were both financial and political decisions. There were more than 6,000,000 square feet of office space occupied by state workers around Capitol Square, with 7,000 parking spaces in 20 different structures. Older buildings were expensive to maintain and to rehabilitate, in order to provide sufficient electrical power for modern technology and to make spaces fully accessible for the disabled. The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically expanded telecommuting, transforming the need for maintaining or building new space for office workers.

The General Assembly agreed to fund restoration of Richmond's Old City Hall in 2016, but required the size of the planned new General Assembly Building to be reduced. Two floors were eliminated from the plans. In a bargain for space between the Republican-controlled legislature and the Democratic Governor, the Executive and Legislative branches agreed to share use of the Old City Hall after restoration.

In 2023, the partisan roles were switched. The General Assembly was controlled by the Democrats and the Governor was a Republican. They disagreed on who had the authority to designate how the rooms would be occupied. The Governor wanted to fill the building with state tourism and cultural agencies, but the General Assembly directed the Capitol Police and the Division of Legislative Automated Systems to move into the Old City Hall building.

the Department of General Services under the control of the Governor manages Old City Hall - not the General Assembly

Source: Virginia Department of General Services, Capitol Area State Owned Buildings and Parking Facilities (Revised June 2023)

During the 2024 session, legislators tried to assert control through language in the budget that would replace the Governor's control over the Virginia Department of General Services with an independent panel. In the final budget compromise, the Executive Branch won the argument. Soon after the legislature ended its session, Governor Youngkin appointed new leaders for the Department of General Services.

Capitol Square, 2024

Source: Virginia State Capitol, Virginia State Capitol and Capitol Square

The state legislators did succeed in blocking Governor Youngkin's plan to demolish the 29-story James Monroe Building next to I-95, which was the tallest building in Richmond. The Governor planned to house those workers in leased office space.

The 2024 General Assembly also anticipated removal of the James Monroe Building, since leasing space would save $450 million over 210 years compared to renovating the building. However, the Executive and Legislative branches disagreed on how to house the displaced workers. The 2024 budget authorized only a study of replacement space options.

There were several possibilities. Demolition of the former office building of the Virginia Employment Commission and its parking garage at 703 East Main Street had created space for constructing a new building three blocks west of Capitol Square. Funding for a $400 million new office building there was included in the capital outlay budget in 2021, but Governor Youngkin cancelled that project. His refusal to spend the budgeted money led to the legislature blocking $50 million requested by Governor Youngkin in 2024 to start planning for demolition of the James Monroe Building.

One option was to move state workers into the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) Annex building at 1401 East Broad Street, two blocks east of Capitol Square. The Annex, constructed in 1963, would become available when that state agency moved its employees to a new site at 9120 Lockwood Boulevard in Mechanicsville in 2025-2026. The Annex had more parking spaces than the former Virginia Employment Commission building on Main Street. Cars using the garage with 600 parking spaces at the Monroe Building would need an alternative, once that facility was demolished.

Another option was to use the Virginia State Lottery building, a 23-story tower known as Main Street Centre. That structure was four blocks west of Capitol Square. Governor Youngkin anticipated many of the workers in the James Monroe Building could move to that location, as well as leased space downtown.

The legislators preferred building a new state-owned office tower as close as possible to the Capitol. They were sensitive to the economic impact on downtown Richmond, which had a high vacancy rate for commercial buildings. The city would be unable to tax state property, but concentrating state workers downtown would generate tax revenue from sales in restaurants and downtown stores.

One legislator said:29

alternative spaces for James Monroe Building workers included 1) Virginia State Lottery (Main Street Centre), 2) former site of Virginia Employment Commission, and 3) Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) Annex

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In August, 2024, a preliminary report indicated the Department of General Services preferred replacing the Virginia Department of Transportation Annex on Broad Street with a new office building. Initial plans were for a 316,000-square-foot building costing $400 million. The new structure would house state workers to be displaced when the James Monroe Building was sold or demolished.

State Sen. Creigh Deeds, a key legislator in dealing with the capital outlay budget, supported that Broad Street location:30

At the start of the 2025 General Assembly session, Governor Youngkin endorsed the Virginia Department of Transportation Annex site at 1401 East Broad Street as the site for a new state office building.

https://arcg.is/yCPqa">

https://arcg.is/yCPqa">

the General Assembly and Governor agreed in 2025 on how to replace the James Monroe Building

Source: Virginia Department of General Services, Updates on DGS Capital Projects - House Appropriations (January 15, 2025); ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The governor also concurred with selling the Virginia Employment Commission site at the corner of East Main and North 7th Streets, and constructing a new Commonwealth Courts Building for the Virginia Supreme Court and Court of Appeals to replace the buildings on 900-908 E. Main Street. The Art and Architectural Review Board (AARB) had already endorsed building a new 13-story high courts complex to replace the existing Pocahontas Building complex.

state officials plan to move the top courts of Virginia to a new complex on Main Street (red circle) that would replace the Pocahontas Building

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Virginia Department of General Services study of options for replacing the Monroe Building concluded in November 2024 that:31

anticipated design of new state office building at the Virginia Department of Transportation Annex site

Source: Virginia Department of General Services, Updates on DGS Capital Projects - House Appropriations (January 15, 2025)

In 2025, a New York developer proposed to build a 35-story tower on the 1.25-acre parcel once occupied by the Virginia Employment Commission at the corner of Main, Seventh, Cary and Eighth streets. The state already was planning to sell the land, since it would not be used for a state office building.

The proposal reflected increased interest in the revitalizing downtown area of Richmond. A different developer was already planning to convert the 20-story Eighth & Main office tower at 700 East Main Street, recently vacated by Dominion Energy, into 290 apartments and a hotel with 200 rooms.32

House of Delegates chamber in 2026

the Beaux-Arts building north of the Virginia State Capitol is the old city hall for Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, Aerial view looking northeast - Virginia State Capitol

the State Capitol originally lacked steps at the southern end, and had no wings

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the city of Washington and territory of Columbia (by William Home Lizars)

the Virginia State Capitol was built on a high spot to indicate the authority of state government

Source: National Archives, Richmond, after the evacuation

the capitol was undamaged in the evacuation fire when Confederates abandoned Richmond on the night of April 2, 1865

Source: Library of Congress, Richmond, Virginia. View of the burned district and the Capitol across the Canal Basin

the Bell Tower was constructed in 1824 to provide security for the government office complex

Source: Library of Congress, Old bell tower, Richmond, VA (1908)

the Virginia State Capitol in 1988, with St. Paul's Church in the background

Source: Library of Congress, Southwest facade, main block, looking northwest

the bell in the Bell Tower, built in 1825 as a guardhouse, still rings to announce each day when the General Assembly is starting a session

![]()

the Jean-Antoine Houdon statue of George Washington was installed in the State Capitol in 1796