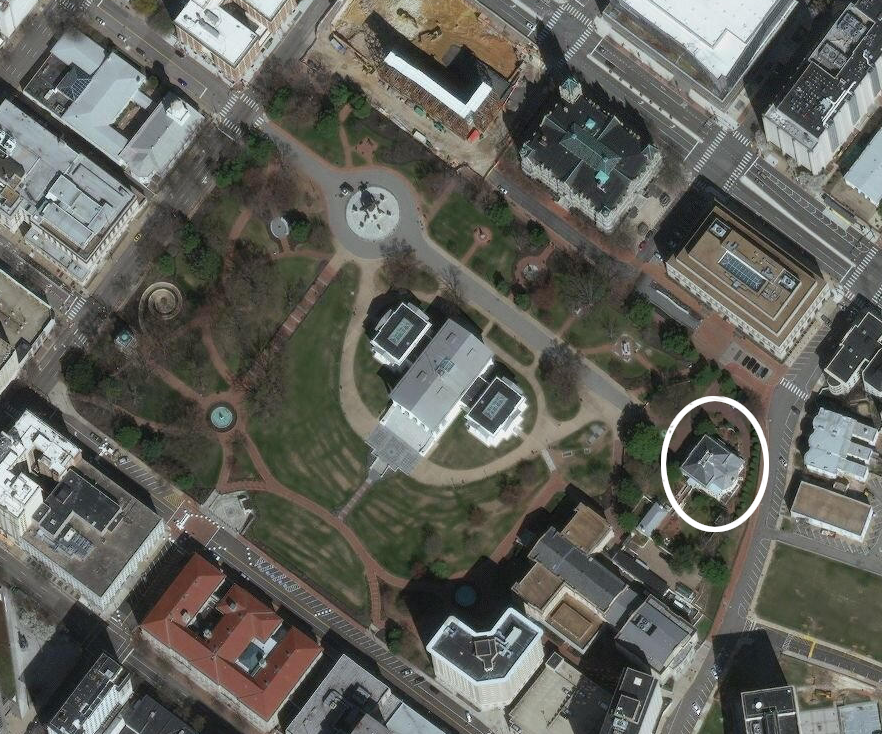

the Executive Mansion, facing the Virginia State Capitol, reflects the Federalist architecture popular at time of construction (1811-1813)

Source: Library of Congress, Governor's Mansion, Capitol Square, Richmond, Independent City, VA

the Executive Mansion, facing the Virginia State Capitol, reflects the Federalist architecture popular at time of construction (1811-1813)

Source: Library of Congress, Governor's Mansion, Capitol Square, Richmond, Independent City, VA

The brick structure that now houses the Virginia governor was completed in 1813, and is the oldest continuously-occupied governor's residence in the United States. The oldest continuously-occupied executive mansion in the United States is the White House in Washington, DC. The second oldest governor's mansion is in Jackson, Mississippi; it was completed in 1842.1

When the capital of Virginia moved from Williamsburg to Richmond in 1780, Thomas Jefferson was the governor. He moved from a "palace" in Williamsburg to a frame house in Richmond, which he rented on Broad Street near Thirteenth Street. The first governor to live in the northeast corner of Capital Square was Benjamin Harrison, who occupied an existing structure there.

According to the nomination form to add the Executive Mansion to the National Register of Historic Places:2

Under the Constitution of Virginia adopted in 1776, the office of governor was designed to be subordinate to the power of the state legislature. When the Virginians were rebelling against King George III, they were willing to create a balance of powers in their new form of government but had no desire to establish an executive branch with authority equal to the legislative branch. The location and design of the Executive Mansion and the placement of the governor's office in the State Capitol reflected the dominance of the General Assembly:3

In 1792, Gov. Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee returned home to discover that his young son Philip Ludwell Lee had died and been buried in the yard of the governor's home. The body was later transferred to the Lee family home at Stratford Hall.

Lee was one of many governors who used enslaved people to cook, clean, and care for them while living on Capitol Hill. The original cookhouse where the enslaved workers prepared meals, a separate building from the mansion house which housed the governor's family, has survived.

That cookhouse/slave quarters was restored by Gov. Terry McAuliffe and is now used in interpretive tours which discuss the life of the enslaved adults and children, in addition to the lives of the elite families at the Executive Mansion. In 2016, Dorothy McAuliffe dedicated the garden to the enslaved workers.

Plaques on the garden wall include excerpts from letters between an enslaved family which had been separated when Gov. David Campbell moved into the mansion in 1838. The governor left Hannah Valentine and younger children at his plantation, Montcalm in Washington County near Abingdon. Michael Valentine and older children were taken to Richmond for the three-year term. The Campbells were slaveowners, but ignored state laws and allowed the Valentines to write to each other.

In 1799, Governor James Monroe refused to occupy the dilapidated frame dwelling. He rented a house in Richmond instead. James Monroe served a second term in 1811, and approved the General Assembly's decision to replace the frame house. Monroe then left Richmond to serve as President Madison's Secretary of State.4

The old structure was sold and moved off Capitol Hill. Construction of the new two-story brick home for the governor started before direct fighting with England began in the War of 1812. Thomas Jefferson had originally proposed a design based on the Villa Rotunda in northern Italy, which he used in part at Monticello. In 1811 state officials adopted a classic Federalist style, and hired a Boston architect to design a new Executive Mansion with a symmetrical facade. The architect, Alexander Parris, also used the Federalist style when he designed what is now called the Wickham-Valentine House on East Clay Street.

Thomas Jefferson suggested modeling the governor's home in Richmond on the Villa Rotunda in northern Italy

Source: Wikipedia, Palladios Villa Rotonda, Veneto, Italy (by Stefan Bauer)

During construction, Governor George William Smith and then Governor James Barbour lived in a rented house at the southeast corner of Twelfth and Marshall streets. The two-story Executive Mansion was planned so the family could occupy the second floor as private space, while official functions could be held on the first floor.

Running water in the house was provided in the late 1820's, during the term of Gov. William Giles. A spring in the front yard was the source.

Since Governor Barbour moved into the completed structure in 1813, several modifications have been made. An iron fence was added in 1820, the balustrade connecting the four interior chimneys was constructed in 1823, a rectangular transom replaced the elliptical fanlight above the front door in 1830, and north and south side porches were built in 1832. A rear addition with a formal oval dining room and kitchen was completed in 1906, moving what had become an interior kitchen from the west room.

Betsy Montague, wife of Gov. Andrew Montague, planned to go in person to the General Assembly to request funding for building repairs in 1906. The funding was ensured when the overweight chair of a General Assembly finance committee sat in a chair in the mansion at a party hosted by Gov. Andrew Montague, days before she made the request. The rickety furniture piece collapsed beneath him, and he was spotted trying to hide the pieces among the palm decorations Afterwards, there were no objections to her request.

Two bedrooms plus a bathroom were added above the 1906 addition in 1914. An addition to create a back hall and breakfast balcony modified the southeast corner in 1938, and the same area was changed again between 1958 and 1962 to add a breakfast room on the first floor and a library on the second floor.

Soon after the start of World War II, security had been so relaxed that a drunken sailor had climbed the latticework outside and climbed in a second story window, perhaps thinking he was getting on board his ship. When the governor and his wife were told by their son that there was a man in his room, they discovered the sailor sound asleep underneath the bed.

In 1955 the iron fence surrounding the house was replaced with the current brick wall. The guardhouse at the front gate was created in 1961, another security feature added during Massive Resistance.5 The interior of the first floor was reconstructed after a 1926 fire. Billy Trinkle, the five-year old son of the governor, accidentally ignited the Christmas tree with a sparkler. The governor was away, but his wife realized after escaping the house that their 15-year old son was asleep upstairs. She raced inside and up the steps, suffering second degree burns on her arms, hands, and legs - was then trapped with her teenage son.

The fire department placed ladders below the window, but they 10 feet too short. Helen Trinkle climbed onto the outside window ledge and dropped into the arms of a fireman. He caught her, breaking his shoulder in the process. The 15-year old then fell safely into the arms of the African American butler for the mansion, Clayton Setgray.

Paintings of early Colonial governors and room furnishings were destroyed in the fire, as was Mrs. Trinkle's Stradivarius violin. Incoming Governor Harry F. Byrd rejected proposals to replace the historic structure, and instead had the interior repaired. The piano had been destroyed, so Gov. Byrd sold the car intended for the governor's use and used the funds to buy a replacement piano.

In 1974, Governor Mills E. Godwin proposed the Executive Mansion should be converted into a museum. He suggested a new home should be established for the governor, somewhere in Richmond's suburbs.

Gov. Gerald Baliles faced yet one more set of proposals for rehabilitating the building, but stopped short of historical accuracy. When told the original color was close to purple and brown, he directed that the exterior be repainted in the current cream/yellow color. The renovation during the term of Governor L. Douglas Wilder was not sufficient; his successor Governor George Allen discovered that the floor joists were too weak to allow dancing inside the building.

Gov. Jim Gilmore and his family lived in temporary quarters while the building was rehabilitated in 1999. All mechanical equipment was replaced, and the basement floor was lowered several feet. Today, the mansion has 13,500 square feet of usable space.6

In the 1999 renovation, the quarters for enslaved people were converted into guest bedrooms. The Valentine-Jackson Memorial Garden was created just outside, to honor children and relatives of Hannah Valentine and Lethe Jackson. Their family members were brought by Governor David Campbell from his Abingdon plantation to the Executive Mansion during his 1837-1840 term in office, dividing the families.

Starting in 2019, under Governor Ralph Northam, the kitchen quarter adjacent to the Executive Mansion was refurbished. The descendants of the enslaved people who had worked in the Executive Mansion until 1865 were pleased to know the history of the workers who built, lived and worked at the home would be told.

The plan was to open the space to the public in stages. First step was to create an education room highlighting the lives of the enslaved workers who served the governors and their families living at the mansion, using for interpretation the space where those workers lived and cooked:7

the Valentine-Jackson Memorial Garden at the Executive Mansion

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

However, public tours of the mansion were stopped during the COVID pandemic.

A new governor, Glenn Youngkin, was elected in 2021. His wife planned to convert the former kitchen into a recreation room for the family or an exercise room for the governor. Those plans were stopped after negative public reaction. When tours re-started in 2022 under Governor Youngkin, the public could not enter the former kitchen and references to the enslaved workers were omitted.8

There was criticism of the public tours when they restarted under Governor Youngkin, because they did not visit the former kitchen space. The tour route had not changed from what was offered under Governor Northam, but plans to expand into the kitchen were not implemented either. Political opponents of the Youngkin tour noted that he had signed an executive order on his inauguration day banning the teaching of "critical race theory," and claimed he was pandering to his right-wing supporters.

In response, the governor's wife stated that the tour would include the garden space next to the kitchen as soon as new construction to meet accessibility requirements of the American with Disabilities Act allowed visitors to reach that area.9

the Executive Mansion is located east of the Virginia State Capitol

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Source: Virginia Museum of History and Culture, First House: Two Centuries with Virginia's First Families