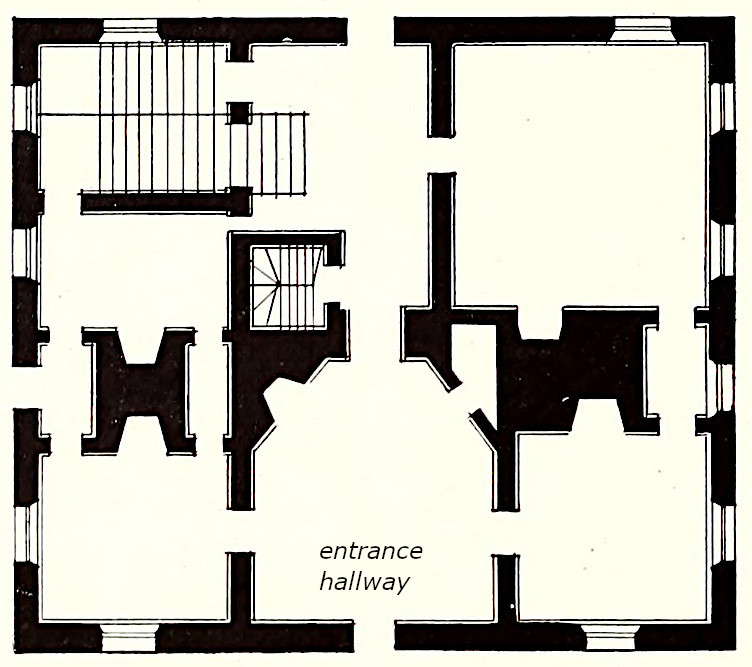

the Governor's Palace started as a square building, with a ballroom added over 35 years later at the rear of the building (top of sketch)

Source: Fiske Kimball, Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic (1922 p.74)

In 1691, a year after Francis Nicholson arrived as the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, he requested from the General Assembly that "a House be built by ye Countrye for the Governor" at Jamestown. That did not happen, but a new college was constructed in the middle of the Peninsula at the headwaters of Queens Creek. The college was named to honor King William and Queen Mary, the new monarchs invited to take the throne after King James II was expelled in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The first brick building, and its replacement after a 1705 fire, established a new tradition of Anglo-Dutch baroque style of architecture which Nicholson supported/

Nicholson was transferred to serve as governor of Maryland. He moved the capital from St. Mary's City to the port of Anne Arundeltown, which was renamed Annapolis in honor of Queen Mary's sister Anne. He was an active participant in the design of the new brick statehouse and other public buildings, and championed creation of public green spaces/gardens with broad vistas from public buildings. Governor Nicholson ensured that the largest lot in Annapolis was developed as a public pasture similar to what later was created as the Palace Green in Williamsburg.

Nicholson stayed engaged with Virginia even while serving in Annapolis. He returned to Jamestown as the colony's governor again at the end of 1698 arriving just after the statehouse burned down. Rather than rebuild it at Jamestown, he took advantage of the opportunity and orchestrated the transfer of the colony's capital from Jamestown to Middle Plantation.

Nicholson was a town planner who designed both Annapolis and Williamsburg. He designed the layout of the new Virginia capital which was named for King William. The Duke of Gloucester Street connecting the Capitol with the College of William and Mary was named for Queene Anne's son, the man expected to become the next king until he died in 1701. Nicholson reportedly ensured the parallel avenue was named for himself.

The first major public buildings to be constructed in Williamsburg were a replacement statehouse named the "Capitol," plus a jail. Nicholson's preference for the Anglo-Dutch baroque style was used for design of multiple structures in the new town.

A house for the governor was planned by Nicholson. The General Assembly purchased 63 acres for it in 1701, but no construction started before Governor Nicholson left Virginia in 1705. During his time in Williamsburg, Nicholson lived in a two-story brick colonial home.1

Construction on a larger house for the governor to occupy and conduct official business began in 1706 after Lieutenant Governor Edward Nott arrived. The first governor to live within it was Alexander Spotswood who came to Williamsburg in 1710. It took several more years of construction before he could move in in 1716. The "palace" became the largest residence in British North America. It was the home of a royal appontee. The entry gate had an English lion on one pillar and a Scottish unicorn on the other, reflecting the union of the two countries in 1707.

the Governor's Palace started as a square building, with a ballroom added over 35 years later at the rear of the building (top of sketch)

Source: Fiske Kimball, Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic (1922 p.74)

The house was funded in part by the General Assembly creating a new tax on the import of people from Africa. The governor's new house, which became known as a "palace" with 61 rooms as Spotswood expanded the design of the structure and surrounding gardens to created an impression of wealth and power, was financed in part by taxing the slave trade. Limestone and marble were imported from quarries on the Isle of Purbeck in southern England. The use of stone and massive brick exterior walls created a sense of permanent authority.

Multiple outbuildings surrounded the house. They were used by indentured servants and enslaved workers to bake bread, cook meals, stockpile ice, do laundry, maintain gardens, raise crops, and manage livestock. Privies provided the necessary bathrooms.

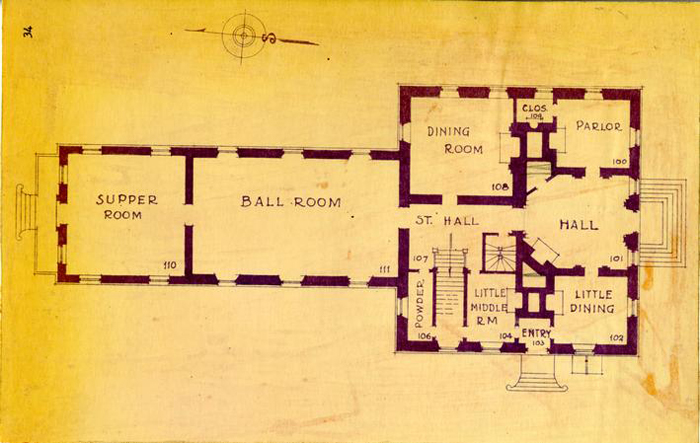

The ballroom was added by Governor Dinwiddie in 1749-1753. No fireplaces were constructed for the ballroom, so evidently it was heated by a stove.

To heat the nearby Capitol building in the winter, Governor Botetourt ordered a triple-decker iron stove designed by Abraham Buzaglo from England. That "warming machine" was moved to Richmond in 1780 and used until after the Civil War in the new home of the legislature.

Botetourt also purchased two smaller Buzaglo stoves to warm the ballroom and the supper room in the Governor's Palace. A "Dutch stove" could burn charcol, but Governor Botetourt used coal. Governor Dunmore imported coal from his own estate in Scotland.

When Governor Dunmore arrived in 1771, he was responsible for furnishing a 12,000 square foot structure and 20 outbuildings used by white indentured servants and enslaved workers.

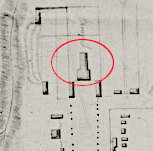

the Governor's Palace was expanded with the addition of a ballroom in 1749-1753

Source: Cornell University Library, Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg, Virginia; Colonial Williamsburg, Architectural Report: Palace of the Governors of Virginia Block 20 Building 3 (p.34)

Seven colonial governors lived in the Governor's Palace; three of them died in it. The wife of Governor Dunmore gave birth to a child there at the end of 1775. The post-christening party at the Governor's Palace was last public social event hosted by a royal governor, held six months before he was forced to flee to a British warship as colonial resistance to royal authority began to turn violent.

In the early morning of April 21, 1776, Governor Dunmore had marines and sailors seize the kegs of gunpowder that were stored in the colony's Magazine in Williamsburg. Gunpowder was a scarce commodity and the British government was trying to prevent an armed insurrection by the colonists, but the removal of the kegs caused men with weapons to fill the streets.

Leaders of the General Assembly appeared at the door of the Governor's Palace and, after discussion with Dunmore, went back into the streets to calm the crowd. The Speaker of the House of Burgesses, Peyton Randolph, sent a letter to Fredericksburg which stopped an armed mob of 1,000 men from marching to Williamsburg.

However, Patrick Henry organized militia members and led them to within 12 miles of the Governor's Palace. That threat was ended by promises to pay for the gunpowder, but Dunmore anticipated violence. He provided guns to both his enslaved workers and white indentured servants and converted his home into a fortress. Swivel guns were placed at the windows and holes were cut into the brick walls to provide ports for firing muskets at any approaching crowd. Lady Dunmore and the children fled to a British warship for two weeks.

On the afternoon of June 7, Governor walked from the palace to the home of his ally John Randolph. He got reports of a plan to seize or assassinate him while walking back. In response, early on June 8 Dunmore and his family fled to Portobello and were ferried onto a British warship. The palace was too isolated from the British forces on the York River for the governor to feel safe; cannon from the warships could not reach Williamsburg.

Soon after the royal governor took his family to safety, his enslaved workers fled to his farm at Portobello. Local residents entered the building and removed the weapons stored on the walls inside the Governor's Palace, plus some of the governor's personal valuables that had been left behind. The weapons ended up in the hands of the "shirtmen" who had formed an independent militia, preparing to challenge British soldiers and marines on warships in the York River.

The furniture, whatever was not looted from the house, and eventually Dunmore's enslaved workers were sold at auction by the Committee of Safety. Proceeds were used to finance the growing insurrection.

No one moved into the Governor's Palace for almost a year until General Charles Lee arrived on March 29, 1776. The Continental Congress had sent Lee to organize the Southern Department, in anticipation of a British invasion at the Chesapeake Bay, Wilmington, Charles Town, or Savannah.

General Lee had no difficulty seeing himself as a leader worthy of residing in the empty palace. He issued orders from Governor Dunmore's old home to consolidate troops near Williamsburg that Virginia officials had scattered from Alexandria to Great Bridge, anticipating a British attack could spark a slave revolt. When it became clear that the invasion would be further south that the Chesapeae Bay, Lee left for the Carolinas.

The Fifth Virginia Convention declared independence and adopted a state constitution choosing Patric Henry to be the first governor on June 29, 1776. Henry and then Thomas Jefferson occupied the Governor's Palace. Jefferson sketched architectural plans to upgrade the house, but those were abandoned when the capital was moved to Richmond.2

A new Governor's Mansion in Richmond was not completed until 1813. Its small size compared to the Capitol building reflects how the state government created after 1776 placed far less responsibility in the office of a governor. The legislators in the General Assembly chose the governor until 1850, and there was no desire to build a "palace" in Richmond for the leader of the less-influential Executive Branch.

After Jefferson moved to Richmond, the Governor's Palace stayed empty until September 1781. Once George Washington and the Compte de Rochambeau brought their armies to Yorktown, sick soldiers were placed in the Governor's Palace. It was still in use as a hospital when it burned on December 22, 1781; the French army spent the winter around Williamsburg. When the Governor's Palace was rebuilt by Colonial Williamsburg, 158 graves were excavated. Those buried on the palace grounds came from the wounded and sick kept at the 1781 hospital or from those who died in the Battle of Yorktown.

The fire could have been an accident or arson. What remained of the ruins was mostly flattened during the Civil War, when soldiers camped at Williamsburg.3

In 1868, the College of William and Mary purchased six acres that were at the entrance to the Governor's Palace. Two years later, the college built the Grammar and Matty School using bricks from the palace's foundation. Williamsburg High School was later build across Scotland Street.

The Mattey School was created in 1870 as a free school for the poor. Funding came through a 1742 bequest to honor a nine-year old named Matthew (Mattey) Whaley, who was buried in the Bruton Church graveyard.

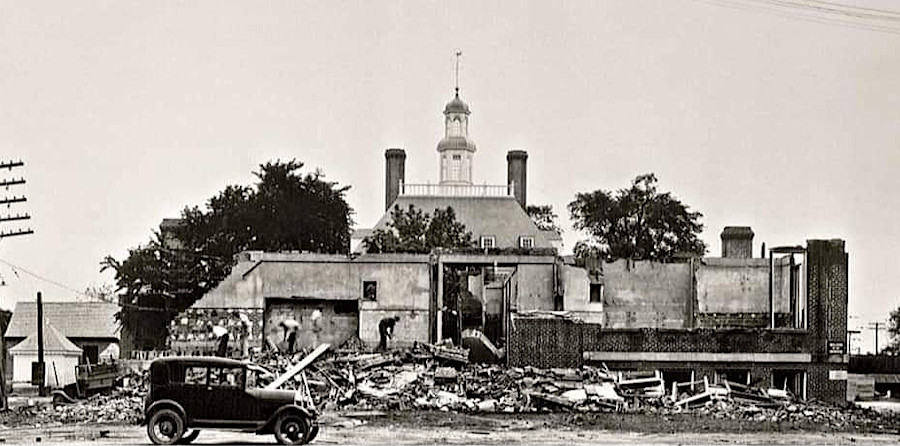

to reconstruct the Governor's Palace, the Mattey School was removed

Source: Thomas Cahill, Facebook post (September 27, 2020)

What became Colonial Williamsburg purchased the Mattey school in 1928. Reconstruction of the colonial landscape of the town was guided by the 1740 Bodleian Plate and a map produced by the 1782 Frenchman's Map. Rebuilding the Governor's Palace was guided in part by a 1779 sketch made by Thomas Jefferson when he was governor. He had planned to alter the building's architectural style, but then he moved with the capital to Richmond and the structure burned.

An archeological excavation in 1930 uncovered the foundation of the Governor's Palace. Items that had fallen into the basement when the building burned were catalogued and used to determine how to create the replacement structure. Reconstruction was completed between 1931-34.4